- Source: FRIEZE

- Author: ANGEL LAMBO

- Date: JUNE 30, 2022

- Format: ONLINE

Jacolby Satterwhite on Seeking Utopia in ‘Pygmalion’s Ugly Season’

The visual artist breaks down his reality-shifting short film for Perfume Genius

A little late to the game, I first encountered Jacolby Satterwhite’s genre-blending work in 2019, during the online premiere of Avenue B (2018-19), a dystopic two-channel video that combined 3D animation with live action footage of the artist being flogged. Witnessing Satterwhite’s work is akin to taking a crash course in experimental maximalism. He embeds achingly personal narratives in landscapes built with a game engine then populates them with images that reference Western art history, queer culture, science fiction and ritualism.

In the years since Avenue B, Satterwhite continues to break ground and reach ever-wider audiences. Career highlights – from my perspective – include his breakthrough show for the 2014 Whitney Biennial, Reifying Desire, which saw the artist place a digital avatar of himself into a world inspired by his mother’s drawings; the animated dance arena he created for Solange’s visual album, When I Get Home (2019); and We Are In Hell When We Hurt Each Other (2020), a mixed-medium installation with an immersive video component, which this year became the first virtual reality work to enter the Carnegie Museum collection. Notwithstanding these impressive achievements, Satterwhite’s most recent project, however, might just be his most ambitious yet.

Jacolby Satterwhite, We Are In Hell When We Hurt Each Other, 2020, HD color video and 3D animation with sound, film still. Courtesy: the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

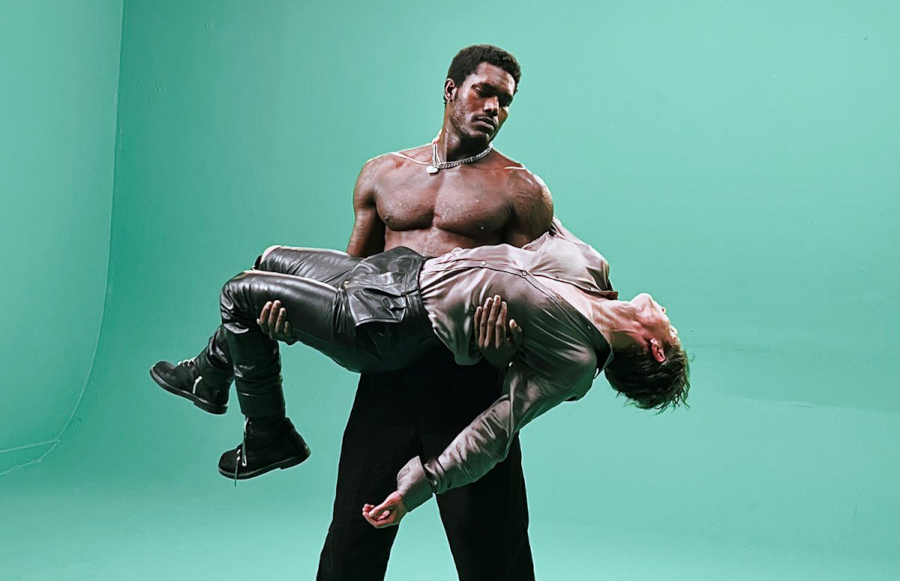

Pygmalion’s Ugly Season (2022) is the 28-minute visual adjunct Satterwhite created for Ugly Season (2022), the latest album by Mike Hadreas, a musician who performs under the stage name ‘Perfume Genius’. The video opens with Satterwhite’s body disintegrating into a network of worlds situated at his joints and chakras. Ever the builder of fantastical dreamscapes, Satterwhite overlays the avatars of pirouetting men in bondage wear with footage of an evangelical Christian congregation overcome by the holy spirit. In another scene, two cyborgs lashed to a travelator made of bike chains convey a bare-chested man, who is cradling a limp Hadreas, through intergalactic space. These vignettes, as wild and attention-seeking as they may seem, are cloaked meditations on desire, human nature, healing and finding utopia.

Behind the scenes of Pygmalion's Ugly Season (2022). Courtesy: Matador Records; Photo: Bryan Ling

Satterwhite’s collaboration with Hadreas builds on work he completed for a 2021 public art commission for the Cleveland Clinic. ‘I was thinking about how to expand the archive that influences my animations,’ Satterwhite told me over a video call, ‘and I tried to move past some of the conceptual precedents that built my earlier work.’ Visiting a community in Cleveland, Satterwhite asked students, teachers, key workers and unhoused people to draw their response to a single question: What does utopia look like to you?

‘In exchange for a USD$25 gift card and five minutes of their time, they drew a schematic diagram or an architectural rendering of how to bring their neighbourhood into a utopian ideal,’ he told me. ‘I eventually amassed an archive of 120 drawings that looked like my mother’s mixed with Jean-Michel Basquiat and Sol LeWitt.’ Satterwhite later turned the crowd-sourced images into the digital ephemera and coded animations that give Pygmalion its esoteric edge. He didn’t stop there either, surveying the drawings again and noting some recurring themes: consumerism, nature, infrastructure, domesticity, religion and philosophy. I asked Satterwhite which of these utopian themes resonated with him the most.

‘Naturally I identify with all of them,’ he told me. ‘I’m not materialist in regard to fashion, but I like other things that are wasteful. I am also a Gwyneth Paltrow Goop healthcare junkie and I like regimens that improve the body and mind. I’m not religious but I have a faith practice that’s eccentric and customized for my own benefit. That’s why I feel like these [drawings] were just a Rorschach test to examine myself’. Therapy, self-help and introspection are all forms of healing, according to the artist. ‘That’s what this film proposes,’ he added. ‘A narrative about someone healing by accepting all the parts of themself’.

Behind the scenes of Pygmalion's Ugly Season (2022). Courtesy: Matador Records; Photo: Bryan Ling

In previous work, Satterwhite has manifested forms of healing through gestural movements that draw on voguing, a dance style created by gay and trans people of colour in 1980s New York. ‘[Hadreas and I] are from the same generation, have very similar queer points of view and we both have a relationship with our bodies,’ Satterwhite told me. ‘I have a relationship to my body and cancer, and Hadreas also has certain adversities,’ he continued, referencing the two years he spent in hospital undergoing chemotherapy as a child. ‘Our work speaks about healing internally and externally.’

Hadreas initially wrote the album as a soundtrack to The Sun Still Burns Here (2019), a live dance performance he co-directed with choreographer Kate Wallich. Satterwhite too has created multiple versions of Pygmalion, including an extended version that goes beyond the YouTube release. He likens the project to Rashomon (1950), a movie directed by the Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa, whose characters tell contradictory versions of the same incident. ‘The way Pygmalion’s Ugly Season works is that there’s a version that operates in Mike’s world and a version that operates in my world,’ Satterwhite explains. In his universe, the project trifurcates into a B-side album, a four-channel video game and a 35-minute fantasy film, portions of which will be unveiled this summer at Front International: Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art.

Site-specific installation of Pygmalion’s Ugly Season (2022) at the Guggenheim Museum TCC Party, New York, 2022. Courtesy: the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

Pygmalion is the culmination of two years of intense creativity for both Satterwhite and Hadreas. Much of the visual narrative in Pygmalion mirrors the lyrical content of the album, which Satterwhite summarises as ‘a lover trying to construct a desirable object and idealizing it to such a large scale that it is unachievable.’ The hypothetical lover is a reference to the Pygmalion of antiquity, a Greek sculptor who falls for his own carving of a woman, which a sympathetic Aphrodite then transforms into a real woman.

If the community in Cleveland, who had their creations brought to life in an animated universe, is the Pygmalion of this story, perhaps this would make Satterwhite Aphrodite. If so, this would be a fitting persona for an artist whose social practice is founded on love – love for his creative collaborators and the communities for whom he advocates through his art.