- Source: INTERVIEW MAGAZINE

- Author: KELSEY LU

- Date: SEPTEMBER 25, 2023

- Format: DIGITAL

Jacolby Satterwhite and Kelsey Lu on Radical Awakenings and Video Games

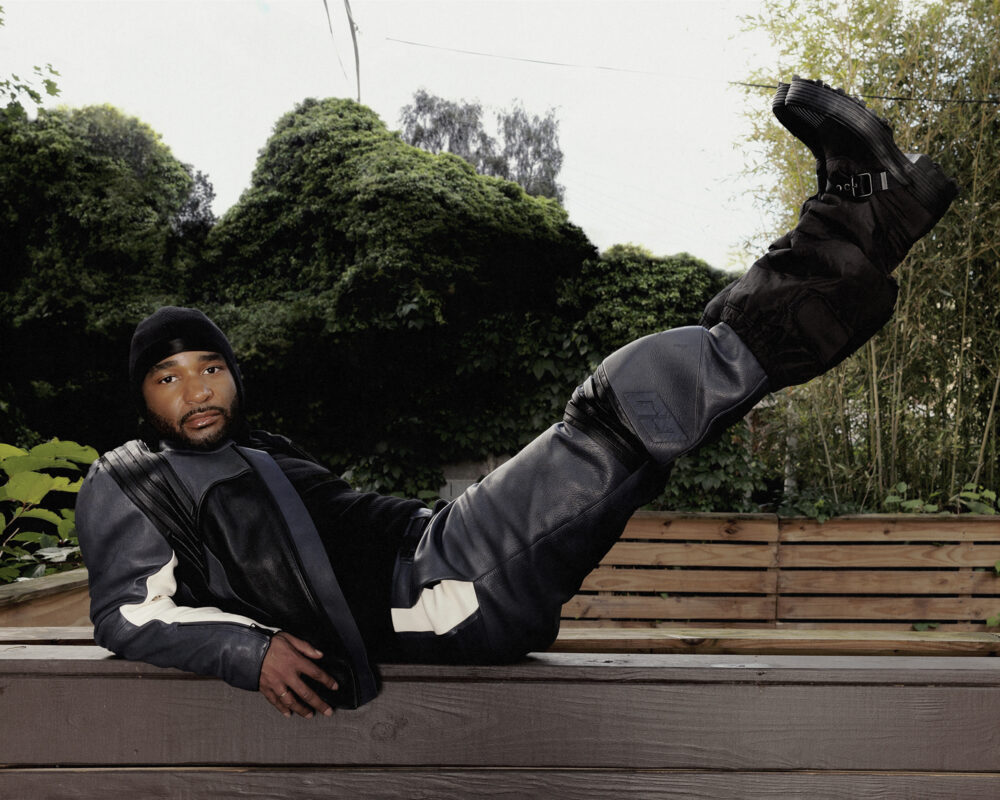

Jacolby Satterwhite wears Coat Loewe. Shirt and Pants Ferragamo. Shoes Camperlab. Durag (worn throughout) Jacolby’s own.

The New York artist Jacolby Satterwhite is in the midst of transforming the Great Hall of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. His vision is a kaleidoscopic installation that blends the queer-coded, video-game-inspired art he’s known for, with soundscapes and treasures plucked from the museum’s esteemed collection. The project, he tells collaborator Kelsey Lu (she’s slated to be “in residence” at the exhibition alongside a slew of other musicians), is a radical spiritual awakening. But when has Satterwhite ever played it safe?

THURSDAY 2:59 PM JULY 6, 2023 NYC

JACOLBY SATTERWHITE: Are we all on?

KELSEY LU: Yes, boo.

SATTERWHITE: I just got back from the Met. We were testing out the sound domes. I’m trying to install speakers in every corner of the Great Hall.

LU: Ooh. I can’t wait to hear what that sounds like. The acoustics in there are so crazy.

SATTERWHITE: We’re conceptualizing the whole project differently because of that. The spine of it is from something I’ve been reading and researching: the Buddhist Metta practice, the Metta prayer of loving kindness. I’ve been writing these long, 200-line mantra prayers and vocalizing them on the score I’m creating with [musician] Nick Weiss. Basically we’re going to have a cappella voices and ambient acoustic jazz sounds, and kind of whisper these mantras throughout the Great Hall. I’m just trying to figure out how to make it work.

LU: As a whisper, it’s almost like a secret code that’s being driven and instilled and reverberating through the halls. So you mean a literal whisper or something that’s slightly imperceptible to people who might not even hear it?

SATTERWHITE: You’ll have to walk into certain areas to hear it. I sort of—sorry, I’m a bit out of it because I haven’t slept.

LU: No worries at all. We’re all a little out of it.

SATTERWHITE: Let me light a cigarette so I can get going.

LU: Boo, light that cigarette. I’m sitting on a fire escape right now, next to four giant spiderwebs. I’m in the Alps for my sibling’s wedding ceremony. Earlier, I was sitting under this 300-year-old tree meditating and pulling up the energy of the Earth and thinking about how I’ve never felt a state of neutrality from the Earth. Being in a place that’s instilled with so much beauty and such immense scale, it’s just so crazy. Just thinking about the whispers that come from within the Earth here, from the crevices of the mountain, that makes me think about your mantras within the Met. Because that space contains so much time.

Jacolby Satterwhite wears Jacket and Pants Gucci. Sweater Balmain. Ring Jacolby’s Own. Shoes Camperlab.

SATTERWHITE: You’re literally speaking my language. I was in Switzerland for 12 days in June in those high altitudes, and I was going into nature and feeling a similar kind of neutrality and queerness for the first time. I also spent the entire spring doubling down on my transcendental meditation practices. I think spiritual mindfulness feels important for this project because the Great Hall is a transient space. It has the most traffic out of any institution in the world. It has 3 million visitors a year. It’s the intersection between art forms from all over the world, from the Middle East to the Renaissance to ancient Egypt. The very idea of an art object is a meditation, so on one hand I’m moving inward, but I’m also turning the Great Hall into a place where I’m bridging gaming technology, this massive art collection, music performance, spirituality, and faith.

LU: The thing about that hall is that it’s not one space. When I was asked to participate—there are different musicians at different times during different weeks throughout the exhibition, and I chose November 11th—11/11. It’s an angelic number that represents new beginnings, self-assurance, and spirituality. You and I have been texting each other at 11:11 whenever it comes up on a clock. It’s almost using time and space as a means of jumping towards something greater.

SATTERWHITE: Yes, I’m trying to bridge a very unlikely dialogue between spirituality and gaming in the same way. In our society, games have been always propagandistic to war and fighting and violence and resistance. I was thinking, what if I created a space that represented several musicians, like you, who are protagonists in the game? Music is a sonic form of prayer—what if I incorporate that with art objects from all around the world? I’m sorry, I’m so sleep-deprived right now. I hope this is making sense.

LU: Speak on it.

SATTERWHITE: I guess what I’m trying to say is that I want people to go to the Met and hear the sound domes and the music and see the collection and be hypnotized toward a much gentler world. I want to be a vessel for artists to express whatever they want and celebrate the people who I asked to work with me. I want to celebrate them because I felt like they have powerful voices that are necessary and can be healing on a monumental level. I feel like when we met each other at the Great Hall, you and I were both seeing eye to eye and we were both transitioning spiritually and mentally. I want to ask, are you getting a chance to deliver what you want in this project?

LU: The Met is a place I grew up going to. I’m from North Carolina, and we would come to New York once or twice a year and we always passed through the Great Hall. I remember that space feeling so vast and expansive. And by asking me, you’re already providing. I think everything’s already there.

SATTERWHITE: The greatest paradox is that we’re choosing the loudest and most chaotic place for this. It’s a cacophony to the extreme. I’m trying to collapse and stabilize that and make it about silence and meditation. This is only the second time in the history of the Met that it’s been used for an exhibition or commission. The world is so toxic, and I was thinking, “How can I create something stoic, using the negative and positive aspects of art history, and consolidate that in a music and gaming performance practice? How can I bring it together to make it coexist in a way that feels sort of secular?”

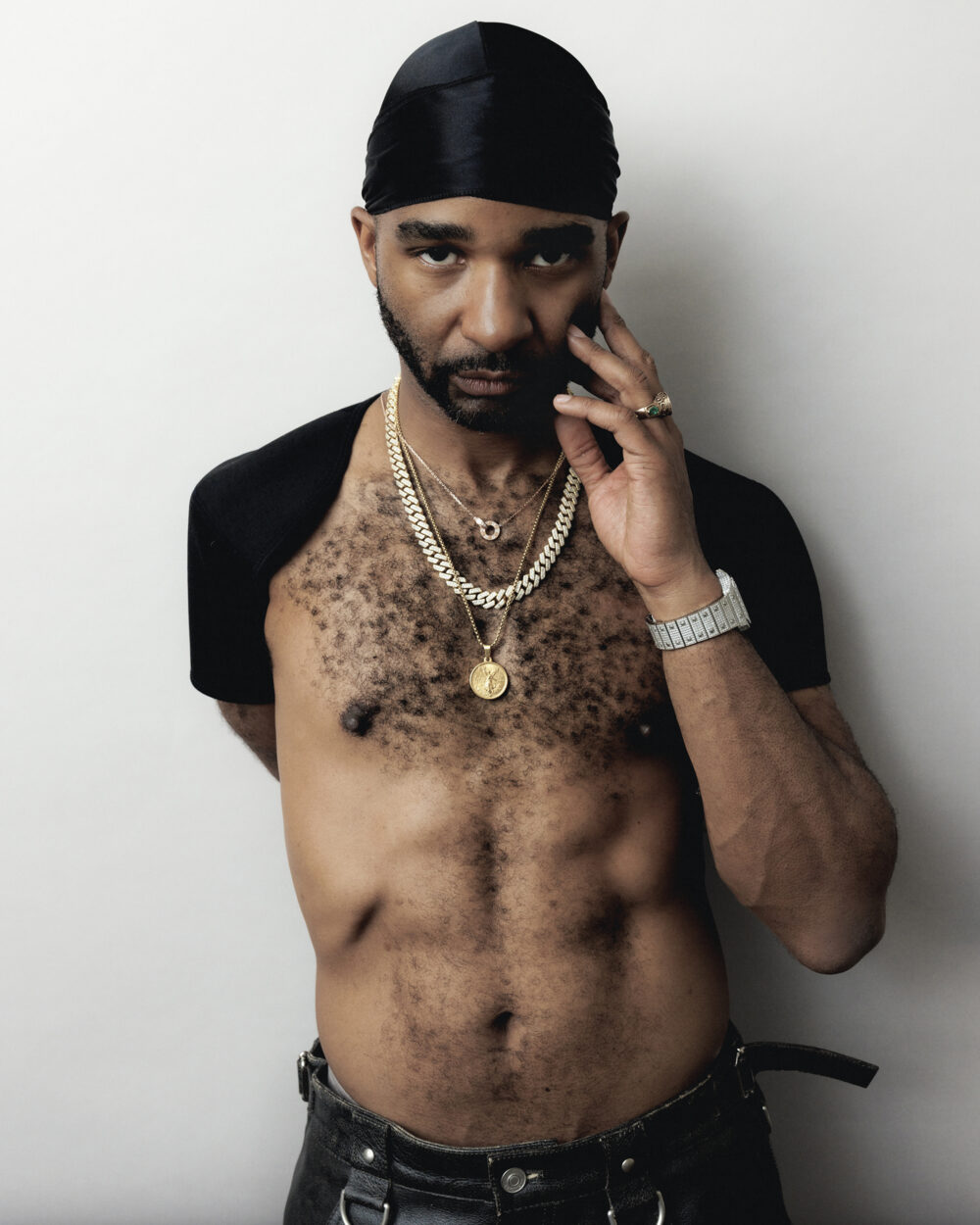

Shirt Stylist’s Own. Pants Givenchy. Necklaces, Rings, and Watch Jacolby’s Own.

LU: Like a secular ritual?

SATTERWHITE: Yeah. Or a unified rhythm.

LU: It’s a kind of reprogramming. That’s my approach within my personal history with classical music. I think about the 18th-century English wood of the instrument that I play. What was the energy that was instilled in that wood during that time? What was the violence that was happening at the time? Then I am instilling it with what I’m crafting. I want to reprogram it with a good message, what I want to send out.

SATTERWHITE: That’s exactly what I’m trying to say. I don’t know why it’s so difficult for me to express it.

LU: Exhaustion, boo. It’s real.

SATTERWHITE: I think this show is about repurposing information until it becomes its own abstract, new form for a potential utopia and new futures. I’m just trying to take away all the toxic meaning of all of the histories that I am pulling from for this show. I want to weave it all together: negative, positive, neutral. I think about that a lot: How do we look into the void and find utopia?

LU: We know it’s there. We have the knowledge. It’s a matter of, “Okay, so then what do we do from here?” Whatever veil has been lifted, the guts have been spilled. They’re on the floor, blood is splattered everywhere. So then what can we do to rearrange it?

SATTERWHITE: [Laughs] I’m laughing, because I feel like I understand exactly what you’re saying. My previous work came from the Trump era and the post-racial uprising era. So much happened when creating that work. It was extreme late-stage capitalism, the 2010s and the hedonism of New York City. And a lot of it was just chaos and addiction and pain and mourning. I was coming of age, and I learned so much from that body of work. But this feels like an opportunity to create forward with wisdom.

LU: Coming out of the pandemic had me going through so many portals, open to the realization that transformation and change is constant. It doesn’t really stop at any point. The intention has been to move to- ward healing and realizing how much time I needed to give to myself to do that healing on my own and understand the tools that I needed to sustain myself to keep going outwardly and outside of pain. I think in my work, pleasure and pain run in tandem.

SATTERWHITE: Me too. My work was all about pain and trauma and reconciling this relationship with my mother and her schizophrenia, but also being an African American male creator in a white-male-canon art world. There were a lot of subconscious resentments that my work was being fueled by. I think the lockdown and being isolated in our apartments for two years, that kind of negative space is sort of an ongoing design principle that is inspiring in the way that we move forward to create. The pandemic, the silence of that singular global moment where everybody went on mute and reflected in different ways—some chaotic, some positive—it was a collective mindfulness. That’s why being in the loudest space in the world, the Great Hall, is a way to reflect on silence. But yeah, I like to hear that you’re moving on from that era of blood and pain.

LU: Pain, pain, pain, pain, pain, pain. Can I say something?

SATTERWHITE: Yeah.

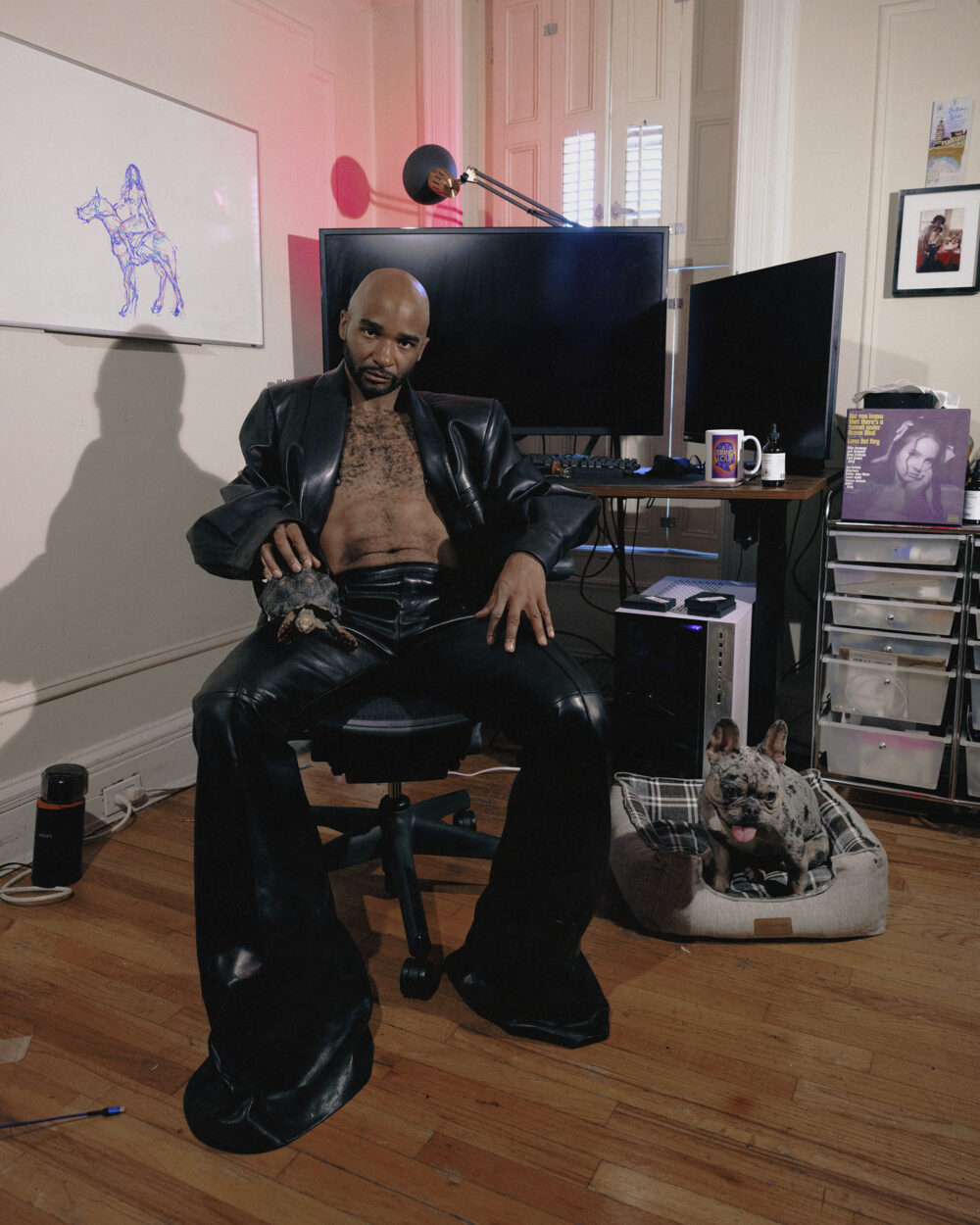

Jacket and Pants Balmain. Shoes Stylist’s Own. Jewelry Jacolby’s Own.

LU: I feel like we both relate to feeling like vessels for pain. Not that we haven’t contained more than that. I think we’ve contained a lot outside of pain, but that pain, at least in our previous work, was a central focus and at least for me, it almost wasn’t a choice. But now I’ve taken the reins to move beyond that vortex.

SATTERWHITE: I’m not Buddhist, but I’ve been finding so much inspiration in the literature that I’ve been reading about how there’s no hierarchy in good and evil. They both can operate in the same composition and dance with one another to create a form that is conducive to betterment. So pain and pleasure are not a binary that oppose one another. They are a union that cannot exist without each other. I think a lot of us artists operate from a very honest and poetic lens, fueled by pain and trauma and poetry and pleasure. We love a melancholic space. But at the same time, there’s optimism in how we try to produce beauty. I suffer from depression and other issues. I’ve always felt like an elephant has been standing on my chest regarding everything I’ve ever tried to create. I feel like I’ve been stifled with anxiety and depression and PTSD that has made taking one step forward so hard. But through a lot of practice, extreme work, research, and diligence, my mindfulness and my mantras have opened up a new potential for feeling this clearness and this emptiness and this acceptance of whenever I do. I embrace it, I dance with it, and I breathe with it.

LU: That’s why your art has a universal message.

SATTERWHITE: I think playing a video game can be a mantra, or a prayer. Mario Bros. level one is a prayer. If you play that every day, you get lost in the game. You tap out the noises happening around you. Say if there is domestic violence happening in the house, gaming is a way to escape that. When I was living in a broken home and I played my video games, it was a way for me to enter a mindful state where I found silence through the tactical memory between the game controller and the TV screen. The same thing happens with music, when you learn to play an instrument, when you listen to a Bjork album every day—oh my god, this interview is the strangest ever. Interview, I’m sorry for the most Marianne Williamson interview of all time.

LU: No! It makes sense.

SATTERWHITE: I haven’t slept in three days and I’m going to Canada to see Beyoncé tomorrow.

LU: Oh my god. Stop.

SATTERWHITE: And I have to finish the first draft for the Met before I go so I haven’t slept. I just left the Met during the sound test to do this interview, and I was on the 6 train and I watched this video of Marianne Williamson at the Democratic debate with Twin Peaks music playing in the background. So maybe nothing I’m saying is coming out right.

LU: I think it’s all coming out as it’s meant to come out. Don’t doubt yourself. Everything is here.

SATTERWHITE: I feel like it’s crazy that I’m from South Carolina and you’re from North Carolina.

LU: We’re just Carolina fools up here.

SATTERWHITE: We have such a kindred vibe. I listened to “Blood” all day during the pandemic and was like, “Who is she?” And here we are collaborating. I love when that happens. It’s the same with Nick Weiss. I discovered Teengirl Fantasy in 2008. I was in graduate school, realizing that my mother’s a cappella, which she created in a mental institution, needed to become a concept album. I didn’t have the mathematical prowess and principle to understand how to work with that technology. And then I heard Teengirl Fantasy. It sounded just like the rhythms my mother was creating. And I cosmically ran into Nick at a bar two years later. Then we started PAT [a collaborative art project].

LU: These are divine interventions, divine happenings.

SATTERWHITE: Thank you for being on this interview with me.

LU: Of course. And please scream for me during Beyoncé.

Grooming: Ayaka Nihei using Mac Cosmetics at Walter Schupfer Management.

Photographer: Michael Wolever

Styling: Stephanie Perez

Photography Assistant: Luca Venter.

Retouching: Amy Anderson and Luca Venter.