- Source: Dazed

- Author: Aindrea Emelife

- Date: July 8, 2022

- Format: Online

Inside the new exhibition exploring sci-fi, myth and Afrofuturism

Now showing at the Hayward Gallery in London, In The Black Fantastic brings together the work of 11 fantastical contemporary artists from the African diaspora – here, Ekow Eshun tells fellow curator Aindrea Emelife all about this must-see show

Cauleen Smith, Epistrophy, 2018. Installation photograph, Cauleen Smith: Give It Or Leave It, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2020–21, © Cauleen Smith, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

In The Black Fantastic, a new exhibition curated by Ekow Eshun at the Hayward Gallery, is a perfectly timed catalyst of excitement and encouragement for the future. Its merits lie not simply in the interesting display of Black artists who, among more well-known names, include those to watch and those whose attention is long overdue. There is an energy about the show that culminates in an inspiring future-facing outlook, fizzing with an energy and a reminder that there is so much more yet to come. This message is at the core of the Afro-futurist agenda.

The term Afrofuturism was first coined in 1993. It is speculative fiction; a future that finds its source material in the past, energised by memories looking to be rewritten and reimagined. At its core, it asks not only who owns the future but who is entitled to reason with, reckon with, and speculate about it. Initially deeply entwined with the African diasporic reasoning, it blooms with many meanings and resists monolithic typification. But at its very core, as a keyword, it seeks to uproot, take apart and reinvent the stagnant cliche of Africa, imagining a new, self-defined agency over a futurist ideal and image that explores the infinite, fantastic possibilities of Black futures.

I would love to know how you how developed the artist list? What were the beginnings of the creative process?

Ekow Eshun: I think with a show like this, the original list was very long. So, what I wanted to do is think about artists who are doing two things at once. Ones whose work begins from an awareness of race, as an idea and as a social construct. I sought to identify artists whose work then proceeds from that point, to offer their fantasies, constructions, and conceits. These works are given licence by the social construction and fantasy of race, so they articulate new fantasies and possibilities, and new ways of imagining Black experience and Black presence. I am looking to find new ways of drawing from Black histories, African-originated myths, and belief systems as well as spiritual practices.

So, all the works in the show, in one form or another, are drawing on some of that territory. And then these are also works, which give themselves licence to embrace beauty, as well as the fantastic, as well as the mythic. These are works, which I suppose offer a proposition of Black being that is unconstrained by a western imaginary, which often confines Black presence in particular ways. I am interested in the gaze as an idea that Black people should only behave or belong to certain places or certain ways of being. These are works that are unconfined in that way, and offer not so much even a riposte to white imaginary, but are intent on constructing their worlds in their ways of seeing.

Were there artists that you felt were completely compulsory to navigating these themes and these ideas within the show?

Ekow Eshun: Take Wangechi Mutu, for example – her entire practice has been about this embrace of myth and African-originated cultural identities and histories. Kara Walker, who in different ways, has been interrogating this territory throughout her long and storied career. Also, Nick Cave, for instance, whose work has this glorious, spectacular quality to it, but is based absolutely on an awareness, a grappling with the precariousness of Black experience in the everyday world. And we see that through his use of his Soundsuits. And through the history of how he developed those Soundsuits initially in response to the beating of Rodney King which has come to symbolise an awareness of the vulnerability of Black presence. Cave is determined to offer another way to move through the world as a Black person, which is how he came up with the Soundsuits, which are gorgeous and spectacular, but also speak to difficult histories.

So just even those three felt foundational to the exhibition, as so many others do too. I hope that within the exhibition you see these artists in conversation with each other. By placing them together in a group show, we come to illuminate different aspects of the artist’s work. Hopefully, the conversation provides a richer and fuller way of looking at each artist individually.

Historically, exhibitions of Black art in ‘the Museum’ has been curated through two frameworks that I like to consider as ethnographic and corrective. This show is an example of doing away with this limited outlook. As we look to the future, how important do you think it is, for Black artists to resist the canon? And to uproot the idea of categorisation solely on geographical, racial, and gender parameters?

Ekow Eshun: I think your analysis is absolutely correct. And actually, before anything else, before I say any further, congratulations on your New York show, Black Venus…

Thank you so much!

Nick Cave, Soundsuit, 2014© Nick Cave. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Mandrake Hotel Collection

Ekow Eshun: I think your exhibition has a great premise and is doing something similar in that same way of absolutely interrogating and trying to push beyond some of these kinds of known constructions of Black historical presence and identity and relationship with an artwork. So the goal is about saying, look what happens when these artists reach towards artistic freedom, cultural liberation, the political assertion of self aesthetics, and self-fashioning. We tried to think about this show as a space of liberation, think about this as a space of inquiry.

The western or European gaze is still present because you can never really get beyond the structure or foundations of that. But here, you also have artists creating or articulating their worlds in their ways of seeing, that are to do with an interrogation of art, historical presence or absence, and political presence and absence, and testing the weight of the Black body, but also about saying, ‘let’s create spaces and scenes and moments of encounter that have their autonomy and agency to them.’

So if we think about Rashaad Newsome’s work – he is conjuring these collage works and form works with a Black body that is asserting itself in these imagined, constructed territories. These are territories where history is foundational, but where possibility, new forms of expression and interrogations of gender and sexuality, in his case, also come to the fore. So that what you see are considerations of an art historical context but also constructions of Black being and Black identity which reach towards the unseen or the unimagined.

One of the things I love about the show is how every single artist sort of headlines their own space. Can you unpack the curatorial considerations for this?

Ekow Eshun: I think it is important to consider the title of the exhibition, In the Black Fantastic. The ‘In’ in the title signals the works, and the exhibition, as a zone of encounter. The proposition I had in my head is that audiences arrived in this space and in different ways, explored or encountered the Black Fantastic. What I hope you see is that from work to work and from space to space in the exhibition are, from one space to another, a different perspective, a different way of looking, and a different articulation of the Black Fantastic.

So, my envisaging here is that the Black Fantastic as an idea isn’t a movement or a genre, it’s a way of seeing. And so I wanted to illustrate and bring alive that proposition by demonstrating, I suppose, or illustrating, the different ways that different artists are approaching the same idea of embracing myth, or speculative fiction or fantasy, and how from room to room, you can have an entirely different approach, which is still founded in a similar territory.

The artists are grouped here under the gathering of the Black Fantastic, but each of them has a very individual feeling – which then illuminates the multiplicity and variousness of Black being and Black individual presence expression. This is about Blackness as multiple lived experiences.

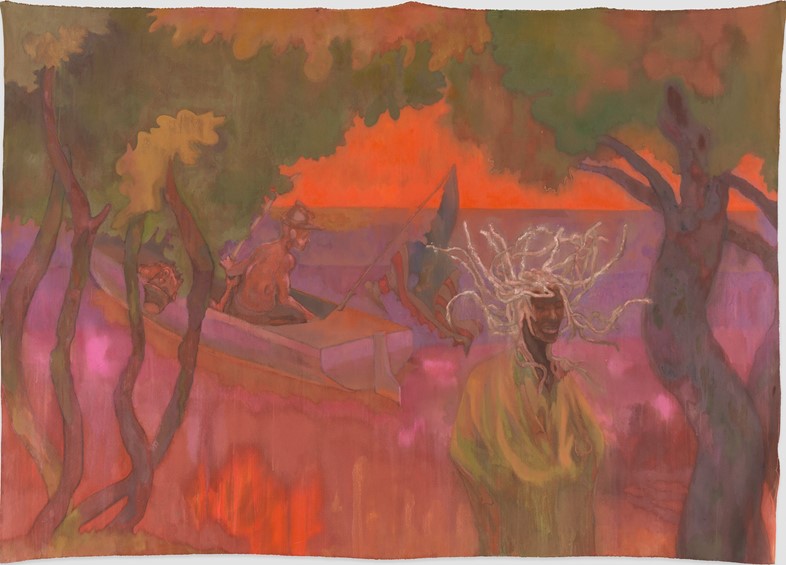

Sedrick Chisom, Medusa Wandered the Wetlands of the Capital Citadel Undisturbed by Two Confederate Drifters Preoccupied by Poisonous Vapors that Stirred in the Night Air, 2021© Sedrick Chisom. Courtesy the artist and Pilar Corrias, London. Photo: Mark Blower

As I was walking through the show, I felt a certain connection between the artists was the negotiations of the Black body. Activist and author bell hooks once wrote of how white patriarchal dominance is mediated by images of Black bodies. She called for demonstrative change, suggesting that “a revolutionary visual aesthetic must emerge that reappropriates, revises, and invents, that gives something new to look at.” hooks is arguing here for new visualisations of a “Black body politic”. As quite a deal of the artwork in the show with the body, do you think a new Black body politic is an important part of the exhibition?

Ekow Eshun: Definitely. It can’t not be. What do we have? We have our bodies, and these are sites of possibility and extreme vulnerability. As you know, the Black body, historically, was trafficked and brought to the west, under duress. The Black body is a site of all forms of physical violence and emotional stress. But the Black body is also one of the routes towards flourishing, imagining and expression. The Black body is also the site of immense pleasure and joy and self-fashioning, and self-articulation. And you see that through the range of different works that you say, conjures over and over, what it can look like, and what it can feel like. They explore how, as a Black person, our bodies hold these different histories and so also a condition of mourning, but also celebration and kinship, and potential for articulation and continued transformation.

What is your vision for the future of Black art display in the UK, but also, internationally. What should we be looking into? What do we as curators, institutions, and historians have to learn? And what sort of uncharted ground do you think is exciting for us to look forward to?

Ekow Eshun: I mean, here’s the thing. Several artists in the show are super experienced and have been working for decades in his territory. But what no one has done today is put them together within this concept, although individually, they’ve been exploring different aspects of shared territory for quite some time.

And I think there remain so many more possibilities. We should illuminate some of the thinking that governs the work of several artists (and I happen to be interested in Black artists or artists of colour, generally). I think what happens when you start to look closer into their work is that you realise (and it, couldn’t be otherwise) that these are part of a much larger spectrum. The closer you look at a single artist or a small group of artists’ work, the more you realise that this is potentially indicative of a whole cosmology. The concept of a wider, contextual setting is where I think there is still potentially work to be done when it comes to artists of colour. And I think there’s a richness that can continue to be explored.

Again, look, I will come back to your show, Black Venus. And I think when you’re thinking about the female presence and female absence, let’s say in art history, or the ways that the Black female presence in art history has been funnelled down particular routes by a western gaze, you realise there’s a lot not just to rewrite here; but there’s a lot of room for writing afresh, for writing anew, for inviting ways of seeing. So much to explore, both historically and in the present moment.