- Source: VOGUE

- Author: RACHEL HAHN

- Date: NOVEMBER 22, 2019

- Format: DIGITAL

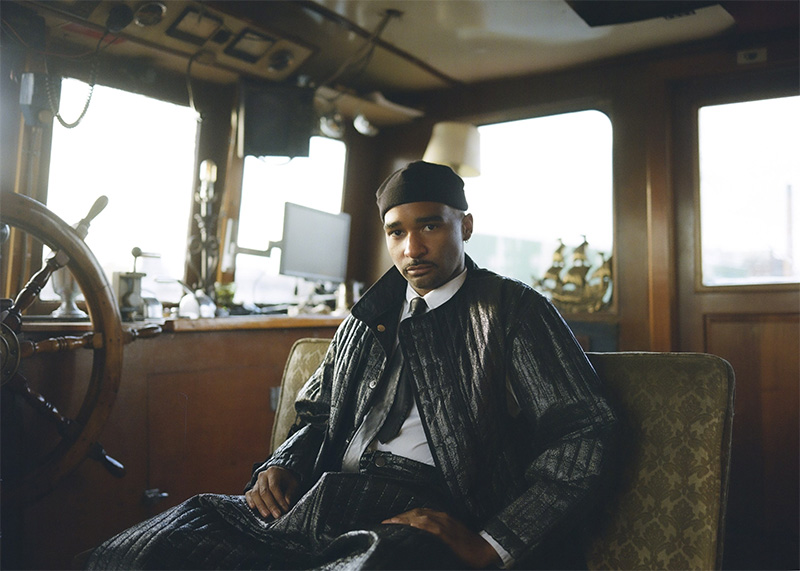

Inside Jacolby Satterwhite’s Fantastical Audiovisual World

Photo: courtesy of James Emmerman

There’s a lot going on, to say the least, in the new video for Jacolby Satterwhite’s “Rain Vs Sunshine.” It’s a song from his recently released album Love Will Find a Way Home, which he recorded under the moniker PAT, a collaborative project with producer Nick Weiss, one-half of electronic music duo Teengirl Fantasy. The screen is split down the middle; on the right, an animated pegasus with laser bright wings flies above a burning forest, and on the left, dancers vogue in a spiderweb matrix resembling a spaceship as turquoise trails extend from their bodies.

This new visual is just a taste of the South Carolina–born, New York–based artist’s carefully rendered, hallucinatory world, one that’s on display at two major institutions at the moment: There’s an exhibit of six massive sculptural relics related to the album, along with moving image, virtual reality, and film, titled Room for Living, up at Philadelphia’s Fabric Workshop and Museum, and there’s a massive solo show, You’re at home, at Pioneer Works in Red Hook, Brooklyn, where Satterwhite and Weiss are performing songs from their joint album tonight.

The Pioneer Works show is the first major institutional solo exhibit for Satterwhite, but his work has been shown at the Whitney Museum (as part of the 2014 Biennial), MoMA PS1, and The Kitchen, to name just a few. Even if you’re not an avid gallery-goer, you’ve probably seen Satterwhite’s work, whether you know it or not—he served as a contributing director on Solange’s visual album When I Get Home from earlier this year. Satterwhite’s animation for “Sound of Rain,” proved to be the stunning visual’s most idiosyncratic moment: Satterwhite built out a coliseum of dancing, almost beatific, figures while a floating horse in the sky referenced Solange’s investigation of the trope of the black cowboy in contemporary culture.

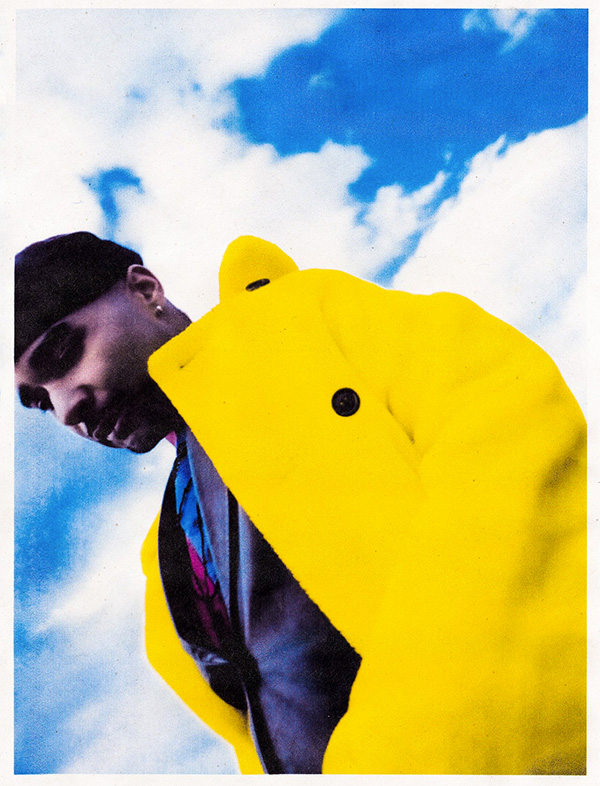

Photo: courtesy of James Emmerman

At Pioneer Works, Satterwhite’s fantastical vision is blown up to outsize proportion to fill out the former industrial factory, the original structure of which predates World War II. Satterwhite’s animated series Birds in Paradise serves as the exhibit’s nucleus; “Rain Vs Sunshine” is an excerpt from the “West Avenue” chapter of the series. “In a way, it’s kind of like a window inside of a window inside of a window in talking about it,” Satterwhite jokes of the genesis of the short clip. Birds in Paradise pulls together many of Satterwhite’s artistic fascinations—there are references to the matriarchal rites of Nigerian Yoruba culture, the ecological undoing of our planet, and banal factory labor, all while animated versions of Satterwhite and anonymous individuals he’s recorded on green screens all over the world dance and gesticulate onscreen. At one point, Satterwhite is baptized by a black naked mermaid, underlining the film’s recurring motifs of regeneration, rebirth, and renewal.

Satterwhite’s Pioneer Works show gives full expression to the many mediums he’s mastered. He’s created sculptures that adorn the walls, themselves plastered with large-scale C-prints, which are the building blocks of his animated films: “I make these very dense still images that look like Renaissance paintings.” There’s also a conceptual record store in the center, made to resemble the now defunct chain Tower Records. Finally, Satterwhite pulls in another deeply personal collaborator for a small, white-walled room within the cavernous industrial space; it’s filled with the drawings of Satterwhite’s late mother, Patricia, who passed away in 2016 after battling schizophrenia for much of her life.

Satterwhite’s mother is a consistent presence in his work—in 2013, he presented a solo show comprising 3D models of her body along with her drawings, for example—and with Love Will Find a Way Home, Satterwhite has fully realized a collaboration between the two of them. The album itself is derived from 155 acapella recordings that his mother self-recorded, either at home or while institutionalized in a psychiatric hospital between the late ’90s and early 2000s; you can hear Patricia’s folksy, gospel-trained voice (she was one of the leaders in her church choir) on “Rain Vs Sunshine.”

Patricia had designs to become a songwriter in the vein of prolific Swedish producer Max Martin, and for years she created mock-ups of sample consumer goods ranging from female self-care products to kitchenware. “She was making these schematic diagrams of common objects and writing songs in order to get them patented and publish, to profit off them on things like the Home Shopping Network or QVC,” Satterwhite describes.

At first, Satterwhite was embarrassed by his mother’s singing. “When I was playing video games with my friends at my house as a kid, she’d be screaming at the top of her lungs, slapping her pencil against the table like it was a metronome,” Satterwhite says. Later on, after studying Dadaism, Fluxus, and artists like Martha Rosler and Bruce Nauman in art school, he started to find parallels between his own art practice and his mother’s. “It was interesting to find sophisticated commonalities between an outsider artist like my mother and these established commercial artists from the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s. It stimulated me to want to push that forward.”

Satterwhite has long used his mother’s drawings and words as inspiration—he would always include her poetic, Gertrude Stein–like sentences and her schematic pictures on his mood boards—but he’s now using his mother’s words and voice more directly. He describes her recordings as “an open source free archive” that he’s tapped into to create a trip hop-inspired conceptual electronic record, wherein he lets his mother’s language guide him. Much like the motifs in his wide-scale animations, the lyrics that Satterwhite curated from his mother’s archive touch on themes of renewal and rebirth. “I built this narrative about making peace with your current condition, being mindful, regenerating renewal, and healing,” he says of the lyrics he’s pulled from his mother’s recordings.

Photo: courtesy of James Emmerman

Satterwhite rejects sentimentality when it comes to working with his mother’s untapped recordings—he doesn’t conceive of his album as a tribute or an homage. “I’ve been working with these archives for ten years, and I feel like they’ve finally resolved themselves in the past three years with this album…but I’m also working with 60 performers when I put them on green screen,” Satterwhite says of the figures that populate his animations, most of which are based on anonymous people that he’s solicited impromptu dance performances from during his travels. Sometimes he’ll capture gesticulations from random people he meets in Fire Island, while other recordings are premeditated. One Grindr-sponsored event found Satterwhite transforming a hotel room at the Standard Hotel into a gay cruising site for nine hours. He wallpapered hotel room walls with green screens, on which he superimposed landscape shots of Central Park, outfitted participants in rare vintage Helmut Lang bondage gear, and recorded their gesticulations. “I had booze filled up to the rim of my jacuzzi and people got really drunk and performed in front of the green screens. You can see a lot of that in the actual film at Pioneer Works.” Satterwhite views his mother’s contributions as equally vital: “When I put her drawings or her sound pieces in my own work, they have the same kind of weight as any other kind of thing that I collect on my hard drive to generate the images and artifacts in the project.”

As Patricia’s schizophrenia developed further, her drawings shifted from enterprising impulse into a cathartic outlet. “The act of gliding the pencil against the page was an act of mindfulness, kind of like meditating, so it was something that she consistently did from morning until midnight until nearly when she was about to pass away. It was something I admired, because I live in a public art realm where I show commercially—I went to art school and I deal with art teachers and students, and the conversation is more about the market and institutions and history,” Satterwhite says.“To see someone making work from a place of necessity, a place of survival, that was inspiring for me. That’s something I want to get to in my own work in order to be more pure, more authentic, and more original.”

Wardrobe by David Casavant Archive