- Source: W MAGAZINE

- Author: Stephanie Eckardt

- Date: APRIL 3, 2017

- Format: ONLINE

In the Studio with Raúl de Nieves, the Would-Be New Star of the Whitney Biennial

The 33-year-old Mexican-American artist had one of the most impressive installations in the 2017 Whitney Biennial. Before he heads off to participate in Documenta, his second major biennial this year, we visit the emerging star in his New York studio.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

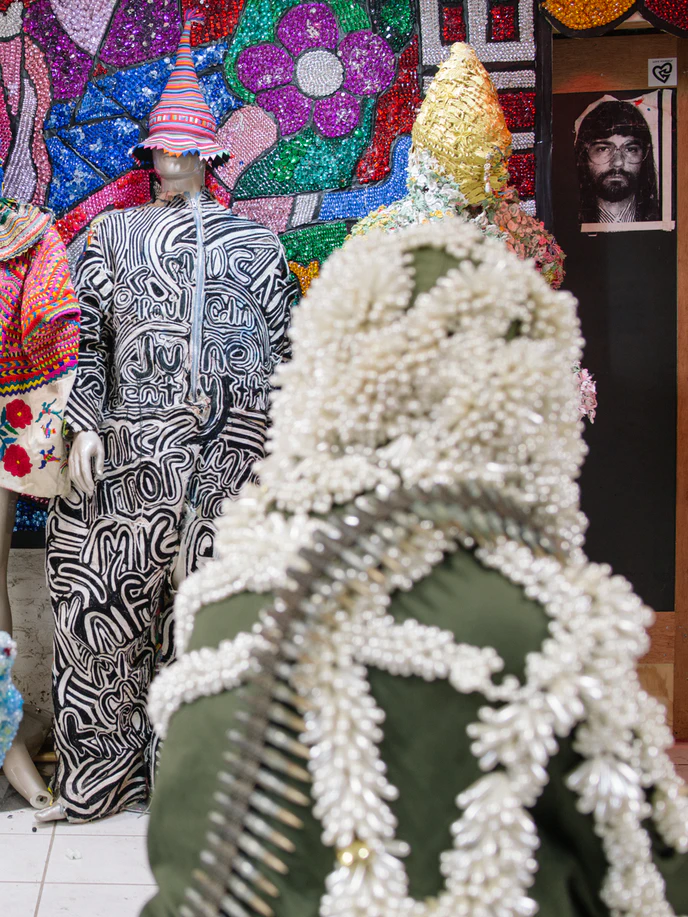

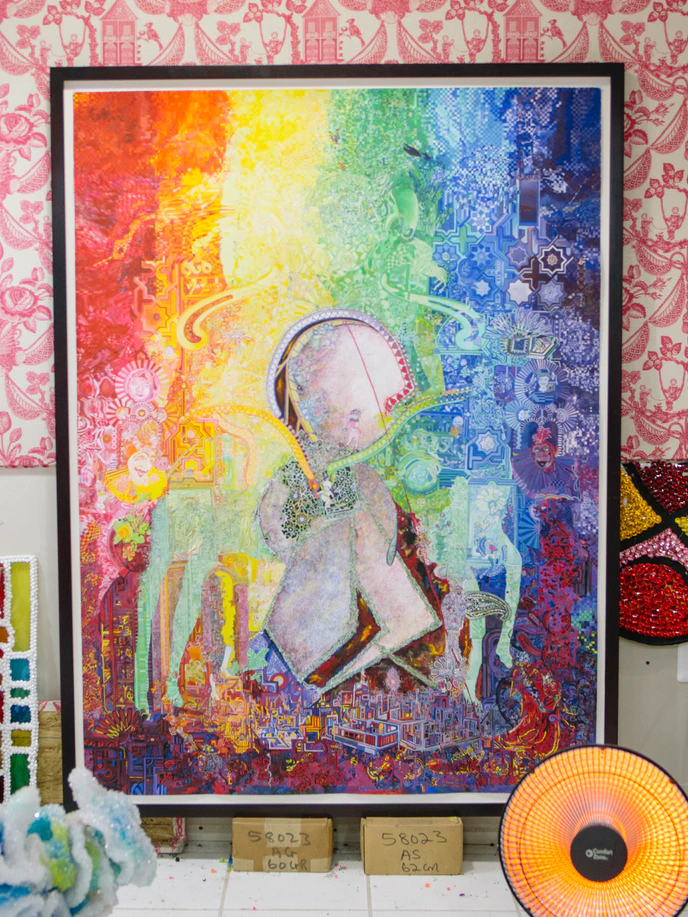

“This actually took me seven years to make,” said the artist Raúl de Nieves on a recent afternoon. He was listening to pulsing electronic music, drinking a green juice, and gesturing to his “little baby,” a balancing act that’s among the most complex of the sculptures de Nieves makes out of thousands upon thousands of beads. “He kept falling, and I was so obsessed with his posture I’d literally kick it,” he added. “So I had to put it in a box and hide it.”

De Nieves, 33, was in his studio in the basement of the club Spectrum, a “queer underground safe space” on the border of Bushwick, Brooklyn and Ridgewood, Queens that’s literally so underground de Nieves will not infrequently look up from messing around with a glue gun and find that it’s suddenly 1 a.m. It’s a world away from the Whitney Museum in downtown Manhattan, where he has recently made a name for himself with a 50-foot installation spanning six of its massive, Renzo Piano-designed windows in this year’s Whitney Biennial, which de Nieves covered in 18 candy-colored panels that “everyone thinks is stained glass, but is really paper, tape, glue, beads, and wood.”

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

The showstopper was among the most-talked about and photographed works at the biennial, until the controversy around Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till sucked up the oxygen around the show. But it’s not the first time the Mexican-American artist turned “mundane objects into something transformative,” as he put it. He was raised in the small city of Morelia, in central Mexico, and “grew up watching people make art out of beads,” de Nieves said, describing how indigenous people such as the Huichols would use the streets as their studios to work on crafts like micro-beading, carved wooden animals, and yarn paintings.

On the other hand, having room to spread, whether for creating his works or installing them, is new for de Nieves, and not just because he’s lived in New York for the past 10 years. When he was nine, de Nieves left Mexico for San Diego, where he shared a home the size of his current studio with his single mother and two brothers. But due to lack of documentation, de Nieves wasn’t able see the rest of his relatives for the next nine years. This distance from his native Mexico, and de Nieves’s pride in its history of crafting, has not only influenced his practice, but infused all of it—beading, sculpture, painting, performance—with a dogged positivity and an almost spiritual dedication to the painstaking process it takes to produce many of his works.

Inside Raúl de Nieves’ Bead-Filled Brooklyn Studio

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

Take, for example, the dozens upon dozens of paintings de Nieves made of the Saint George slaying the dragon, an empowering scene he became obsessed with in part because it reminded him of his mother when he first started his artistic practice in San Francisco, long before he was plastering words like “PEACE,” “TRUTH,” and “HARMONY” across the Whitney Museum. Having moved there for art school, which he then decided was too costly, de Nieves instead “started painting this image over and over again.” It would be his own education.

“The idea in my head was that I would paint 50 of them and act like each one was painted by a different student, so I would feel like I was doing some sort of exercise you might be doing in school,” he explained.

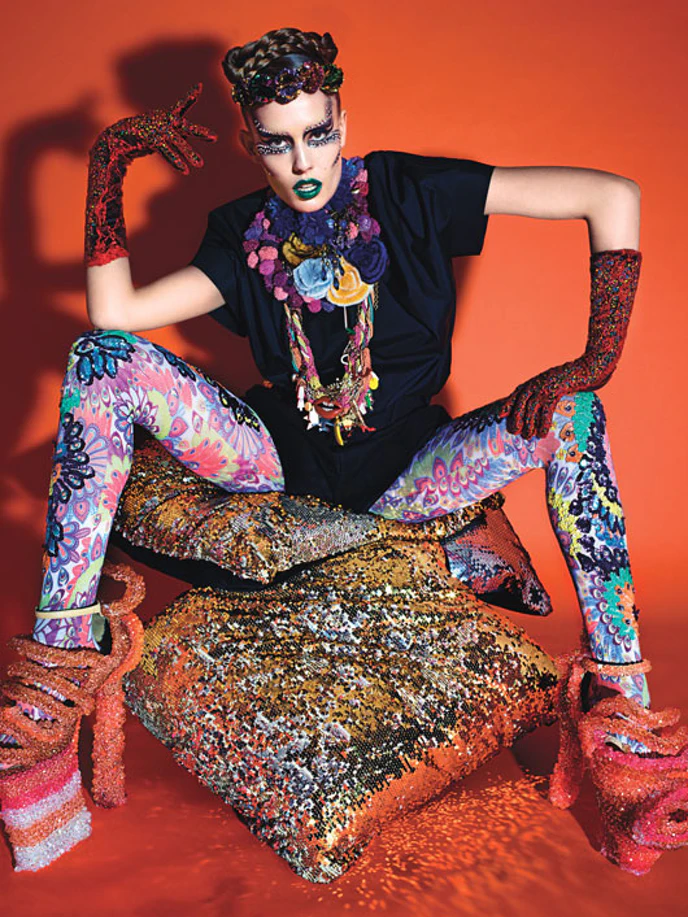

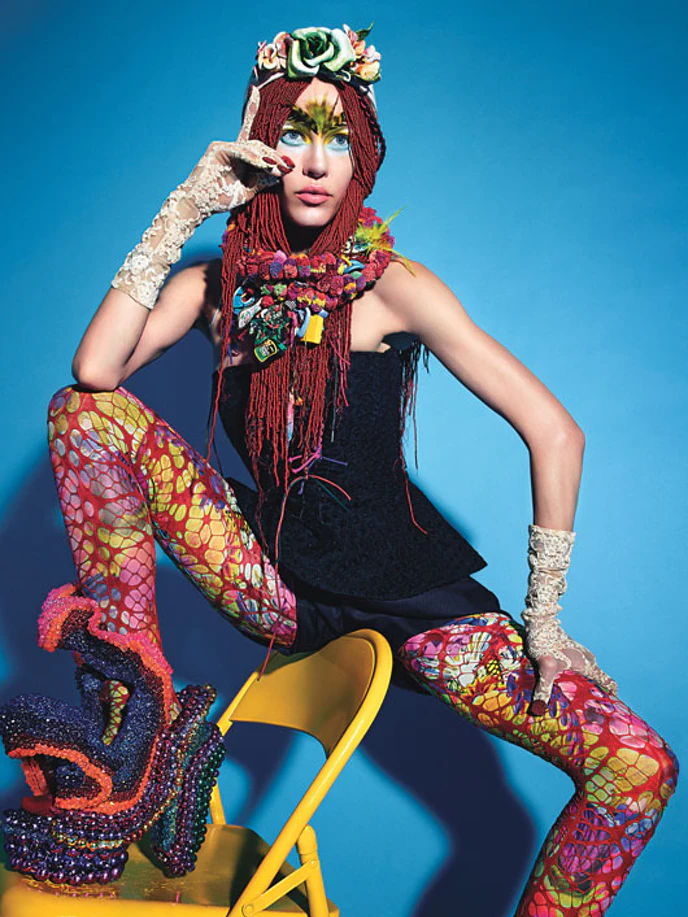

De Nieves still has plenty of Saint Georges around his New York studio, along with other vestiges of San Francisco: beaded sculptures, elaborate costumes, and bedazzled panels, many of which work off of de Nieves’ knowledge of furniture and jewelry he picked up from working in a Victorian home-based antique shop. Though often over the top, many are in fact still quite practical, like the shoes he makes that resemble sculptural abstractions, even if de Nieves, never one to be overly precious with his materials, has kept them mostly wearable—much to the delight of the stylist Panos Yiapins, who had Mario Sorrenti photograph them alongside pieces by Fendi, Gucci, and Dolce & Gabbana in a W story in 2013.

Rave New World

Dolce & Gabbana rayon and silk appliqué top. (From top) Pebble London pom-pom and tassel necklace, Butler and Wilson charm necklace, Pebble London charm necklace; stylist’s own Swarovski Elements lip piece.

Beauty note: Lime-colored lids come courtesy of Dolce & Gabbana Smooth Eye Color Quad in Dazzling.

Photographer: Mario Sorrenti Stylist: Panos Yiapanis

Fendi cotton shirt and shorts. (From top) Gucci crystal flower necklace, Pebble London pom-pom necklace, Butler and Wilson charm necklaces; Raul De Nieves shoes; stylist’s own flower necklace, and gloves and tights throughout.

Beauty note: Bling out your eye makeup with Nordstrom Eye Gems in Heavy Liner.

Photographer: Mario Sorrenti Stylist: Panos Yiapanis

Stella McCartney cotton blend top. Giorgio Armani silk shorts. InDecorous Taste headband; (from top) Pebble London pom-pom necklace, Butler and Wilson charm necklace; Raul De Nieves shoes.

Beauty note: Trace a powdery blue line under lower lashes with Estée Lauder Pure Color Intense Kajal Eyeliner Duo in Black/Blue.

Photographer: Mario Sorrenti Stylist: Panos Yiapanis

Escada cotton blazer. (From top) Missoni choker, Pebble London pom-pom necklaces.

Beauty note: Slick glistening green and purple on lids with Sephora + Pantone Universe Color Cube Lid Liner Stain in Emerald and Make Up For Ever Aqua Cream in 26, respectively.

Photographer: Mario Sorrenti Stylist: Panos Yiapanis

Carolina Herrera silk chiffon blouse and silk faille dress. Sorcha O’Raghallaigh eye piece; (from top) InDecorous Taste necklace, Heaven Tanudiredja necklace; InDecorous Taste bracelet.

Photographer: Mario Sorrenti Stylist: Panos Yiapanis

Chloé silk crepe top, silk organza top, and silk crepe skirt. Bart Hess headpiece; (from top) Pebble London pom-pom necklace and charm necklace, Elephant Heart necklace; Raul De Nieves shoes; stylist’s own embellished mask.

Photographer: Mario Sorrenti Stylist: Panos Yiapanis

Calvin Klein Collection silk and cotton blend bustier, silk crepe organza shirt and skirt. (From top) Heaven Tanudiredja necklace, Pebble London pom-pom necklace; Pebble London necklaces (worn as bracelets); Raul De Nieves shoes.

Photographer: Mario Sorrenti Stylist: Panos Yiapanis

Sportmax cotton twill blazer. Versace satin shorts. Pebble London pom-pom necklaces and charm necklaces; Versace fringe belt; Raul De Nieves shoes; stylist’s own headpiece.

Beauty note: Perfect your canvas for striking makeup with By Terry Cellularose Brightening Serum.

Photographer: Mario Sorrenti Stylist: Panos Yiapanis

Givenchy by Riccardo Tisci silk blouse. Pebble London crown; Givenchy by Riccardo Tisci choker; (on right hand) Pebble London necklace; (on left hand) Butler and Wilson necklace; Raul De Nieves shoes. Versace triacetate blend blazer, satin top and shorts. (From top) Elephant Heart bubble necklace, Reid Peppard for Phoebe English necklace (both worn as headpieces); Butler and Wilson necklaces (worn as bracelets); Raul De Nieves shoes.

Photographer: Mario Sorrenti Stylist: Panos Yiapanis

Céline silk and polyamide dress. Fred Butler headpiece; (from left) Pebble London charm necklace, Butler and Wilson charm necklaces, Missoni choker.

Hair by Recine for Recine Luxe Hair Oil by Rodin; all wigs stylist’s own, styled by Recine; all eyebrow appliqués stylist’s own; makeup by Aaron De Mey at Art Partner; manicures by Yuna Park at Streeters. Models: Aymeline Valade at Women Management; Doutzen Kroes at DNA Model Management; Nadja Bender at NY Model Management; Caroline Brasch Nielsen at Marilyn Agency. Prop and set design by Philipp Haemmerle. Lighting technician: Lars Beaulieu; digital technician: Xanny Handfield. Photography assistants: Johnny Vicari, David Shechter. Fashion assistants: Helen Rendell, Ai Kamoshita, Andreas Grill, Philly Piggott.

Photographer: Mario Sorrenti Stylist: Panos Yiapanis

That same year, Carine Roitfeld had Karl Lagerfeld photograph de Nieves’s shoes for Harper’s Bazaar, and de Nieves created a set of custom necklaces for the boutique Maryam Nassir Zadeh. All that fashion collaboration has made de Nieves even more determined to link up with another spectacularly long-haired personality: Gucci’s Alessandro Michele.

“I’m a dreamer,” de Nieves said with a shrug, which further accentuated the giant blue bow around his neck he’d picked up at a wholesale shop. He intended to bedazzle it himself, after seeing a similar $1,000 version at the Gucci store, where he’d recently bought a pair of platforms after making “a little bit of money.” “They’re so beautiful, but I f—ed them up already,” he added. “I wore them to the biennial opening and partied really hard, so they got scuffed.”

Photo by Paul Quitoriano, Visual Editor: Biel Parklee.

De Nieves will soon need those shoes for more openings. Next up is another major biennial, Documenta, where he’ll be performing in some of his elaborate garments crafted from beads and patches, which are also on display at the Whitney. Then there’s a residency in Mexico, a project on Fire Island, and another couple of residencies in Italy and Greece.

Still, de Nieves is staying grounded. Every day, he heads to his studio. “I think for me, staying in is a form of sickness,” he said. “I like coming here. It humbles me a little bit more, because I walk in here and I’m like, Woah, I’m crazy. And I like to think I’m crazy,” he added, rolling up his sleeve to show off a recent tattoo. It read, in a barbed-wire scrawl, “loca.”