- Source: JOAN MITCHELL FOUNDATION

- Author: JENNY GILL

- Date: AUGUST 4, 2022

- Format: DIGITAL

In the Studio: Raúl de Nieves

Raúl de Nieves in his studio. Photo by Ambera Wellman.

Raúl de Nieves is a Brooklyn-based artist and a 2021 recipient of the Joan Mitchell Fellowship. We interviewed him about his work and studio processes in June 2022. The following is an edited transcript of that conversation.

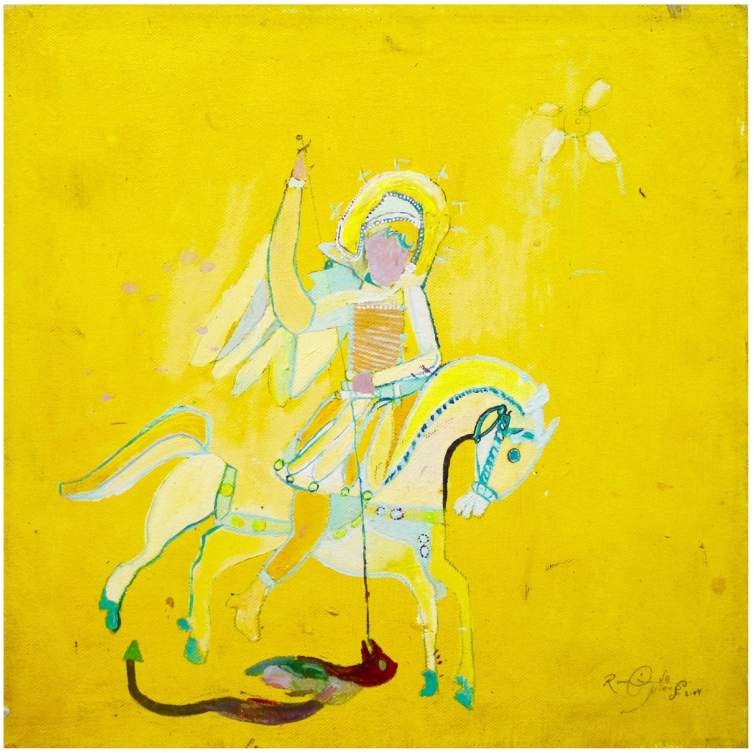

When I started making art, I was mainly focused on 2D work. There was one subject that I was painting quite often, which was an image of St. George and the dragon, which I found to be a really great motif to take on. When this image was presented to me, I was in San Francisco. I had just moved there and I had applied to CCA. I was 19 years old, and I think there was a form of despair because I was like, oh my gosh, this school is going to cost me like $220,000. As a 19 year old, I was like, what does that even look like? I think about it even to this day and I don’t understand it. So I decided to not go to the school, and then was like, well, I need to find my own guidance. For some reason, this image became like a teacher of mine.

The story goes that there is this dragon that’s housed next to a pond near a town. And now this dragon has to have some sort of conversation with the rest of the town, because the town needs the water in order to survive. The dragon gets painted as a demon or someone that’s creating problems. So the town starts to feed him whatever they can in order to get a drop of water, until they’re starting to run out of food for their own needs.

Raúl de Nieves, St George and the Dragon, 2003–05. Mixed media, 13 x 13 inches.

Fear is, I think, the pivotal point of this character—that people were fearing this dragon monster demon. So St. George decides that he’s going to defeat this fear. And once he goes, he realizes that it’s not a dragon, it’s literally a snake. He brings the snake back to the town and says, “This is what we’ve always been afraid of.” Nobody knew what this dragon even looked like.

I felt that the story that was being told through this character had so many facets of understanding. Obviously, it comes from a religious background, but when I think about work that is made in times past up to the times now, there’s a sense of spirituality that I always find a connection to. So this image really allowed me to feel that I could become each one of the characters being portrayed in this body of work. For me, this story really resonates as this way of focusing on finding what it is that we are afraid of in order to defeat it and to learn from it. To become friends with those fears so that you really could be that like inner strength for yourself.

When I moved to New York, I started to develop more of a studio practice, and really started to experiment with materials. I suddenly became so aware of things that I recognized in my upbringing, which was this craft motif. The notion of the hands and the way that I was reminded of how work was made in Mexico really reflected upon things that I wanted to investigate.

Raúl de Nieves, Try cry try, 2019. Artist worn shoes, fiberglass, beads, glue, costume jewelry, light box, acetate tape, 36 x 30 × 30 inches.

The bead became a very prominent material in my work that I still use often. I’ve been accumulating beads for quite a while, just trying to understand how accumulation really builds a new way of understanding time and process. Apparel is a huge aspect of my practice, because I feel like it really gives you a sense of who you are—the way that we present ourselves to the crowds, and to ourselves, too. I think about what gives us that inner strength to be that person that we think we are, or that you want to become. I started using personal items like my shoes to unfold these moments of my life, through the idea of adornment—like taking this shoe and just accumulating it with this craft material, the bead, so that I could somehow understand how things were slowly changing.

When I’m working in my studio, I’m constantly thinking about the way these objects can actually have movement and activation. These shoes that were once worn by me are now these abstract, almost natural formations of time. A lot of people say that my work reminds them of coral reefs or bacteria growing onto an object.

Raúl de Nieves, Basilio, 2019. Tape, acetate, glitter, house paint, and wood. 41 x 41 inches each, 704 x 176 inches overall.

The materials that I’ve chosen tend to be things that are readily available—really just what’s in front of me. And I’m trying to figure out how to shift its relationship to what we understand that it does. Like making a faux stained glass window out of paper and tape was something like a fantasy. It’s something that comes from a traditional way of seeing artwork being portrayed, as stained glass, but obviously having the production quality to blow glass and to cut glass and use steel really requires a larger studio practice. So I think the facade and this idea of make believe has always been another aspect of how I create. It sustains its architecture and creates the illusion. For me, that was another way of realizing that we have this aspect within ourselves to just look around and find what is in front of us to reintroduce it to a new language.

My last exhibition, Carnage Composition, which was at Company Gallery in May, is about this idea of what I call the Book of Hours. It’s about the hours that we spend trying to just realize what is happening in our surroundings and in our heads and trying to manifest this abstract notion. In the exhibition, there’s sculpture, there’s costume work, there’s painting, there’s installation, and it also has a performative quality, because I think as you experience these exhibitions, you start to realize that these objects do have a connection back to the body. You want to think about how they’ve been activated and why they’re standing still.

Raúl de Nieves, installation view, Carnage Composition, Company Gallery, New York, 2022.

Raúl de Nieves, installation view, Carnage Composition, Company Gallery, New York, 2022.

The main sculpture in the Carnage Composition exhibition is titled The Death of Every Days, and it’s this human/snake being in contraction with this architecture of iron. This work really has shifted the way that I’m thinking. I think this goes back to the idea of having an outside source help you to realize a bigger picture. The metal work was conceived through an idea, but I sought out a fabricator to help me put this thing together. That was one of the things that the Joan Mitchell Fellowship has allowed me to do, because I know I have this much money to experiment and upscale my practice. Like, not everything needs to be made out of paper and tape. It’s a grant, and it’s a way to just develop new ideas, but also to build new relationships beyond just the current projects. Like now me and the metal worker are like, “When can we start a new project?”

I think this work really has this aspect of where I started and where I’m going. This idea of building off a shoe to then create an almost life-size sculpture. It’s still made out of beads, so the core is this almost fragile material, but now it’s suspended through these beams of steel that create this new narrative. It’s like the marriage of two things that maybe shouldn’t be together, but now they actually make sense.

I think this piece is about evolution. I worked on it for almost two years and it had an earlier iteration. It was supposed to be for an exhibition at the ICA Boston, where I made a series of these sculptures that are all like a metamorphosis of a horse and a human. This specific sculpture was the last one that I was working on, and I knew I was being extremely ambitious with its size and the weight of it all. So, it didn’t end up making the show because there was an accident that happened to it during transit, moving it from the studio to the museum. It got a crack on it. So once it had a crack, I was like, okay, well, let’s put that thing aside and I’ll think about it later.

Raúl de Nieves, installation view, Carnage Composition, Company Gallery, New York, 2022.

So for awhile, it was sitting in the back of my studio, just taking up space. But it was like when an accident or a mistake happens, you learn so much from these experiences, because it’s the time where you’re like, “what happened to this that is now giving me an opportunity to think of how I can fix this problem, or learn from it?” For me, it wasn’t about fixing this sculpture. It was about seeing what would happen if I pulled it all apart. So it gave me an understanding of this evolution of itself. And I think that’s why even the title, The Death of Every Days, it’s almost like, in an everyday action, we learn something new, and sometimes things resonate longer than others, but it gives you this idea to remember that.

I think the hardest times we’ve experienced are the times when we’ve learned the most about who we are as people. You get to know yourself sometimes more through the mistakes that you’re making, because you don’t want to keep going back to the same mistake, you want to move forward. And I think that’s something that my art practice has always given me—this relationship to really see an actual image of myself within the work. It’s a constant realization of learning something here. So I think this work also really summed up what I was feeling through this new way of experiencing life over the past two years, with COVID showing us that things have to change. That we need to evolve as humans and figure out a new plan.

Raúl de Nieves, installation view, Carnage Composition, Company Gallery, New York, 2022.

When I’m making things, I am trying to build a narrative somehow, but not have it be this concrete thing where people have to see exactly what I’m doing. I think within my practice, people constantly reference this idea of my culture reflecting back into the work. Even going back and talking about St. George, there is this almost religious motif that goes back into it. I think it is because I am connected to these motifs of using these traditional ways of thinking and creating sacred spaces at the end.

The gallery is an experience for the viewer. It allows you to see or think, maybe, what’s going inside the mind of the artists. But then even through your experience of these situations, it’s almost like you’re also allowed to tell your own story of what’s happening. When I go back and think about St George, it has a very prominent historical idea, but I’ve been able to tell the story in a different language. So I think that’s something that’s really important for me to continue to allow for others to just be able to connect to things in their own way, and find themselves in whatever aspect it is.