- Source: THE NEW YORK TIMES

- Author: JON MOOALLEM

- Date: MARCH 23, 2017

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

In the Land of Giants

Communing with some of the biggest trees on Earth.

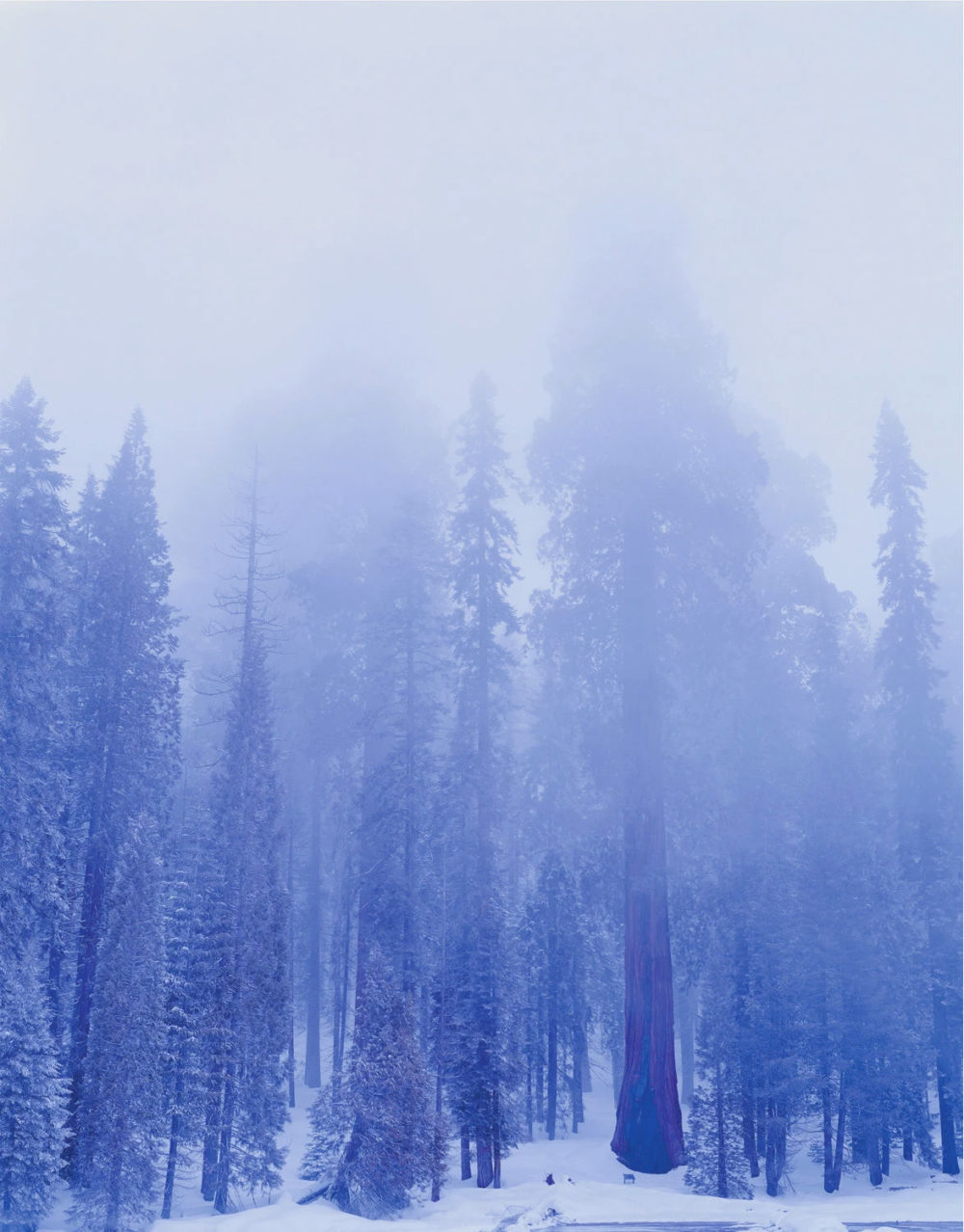

Titans in the fog in Sequoia National Park, California. Credit David Benjamin Sherry for The New York Times

The trees are so big that it would be cowardly not to deal with their bigness head on. They are very, very big. You already knew this — they’re called “giant sequoias” — and I knew it, too. But in person, their bigness still feels unexpected, revelatory. And the delirium of their size is enhanced by their age, by the knowledge that some of the oldest sequoias predate our best tools for processing and communicating phenomena like sequoias, that the trees are older than the English language and most of the world’s major religions — older by centuries, easily, even millenniums. The physical appearance of a tree cannot be deafening, and yet with these trees, it is. Facing down a sequoia, the most grammatically scrambled thoughts wind up feeling right. Really, there’s only so much a person can do or say. Often I found myself expelling a quivering, involuntary Whoa.

The first time that happened, I was driving into Sequoia National Park from the foothills of central California’s Sierra Nevada, south of Yosemite. Suddenly, the Four Guardsmen came into view: a tight quartet of elephantine sequoia trunks through which the road passes. The trees have tops, too — those trunks lead to crowns — but that’s immaterial; the trunks are all you have a hope of registering from inside your car. They fill the windows and function as a gateway. They were like living infrastructure, rising out of the snow.

The rental-car company had given me a squat Fiat micro-S.U.V., which, though it was equipped with all-wheel drive and seemed to be handling capably enough, was so strikingly unbrawny in appearance that crunching up the icy, winding mountain road, I wasn’t brave enough to push it any faster than a feeble crawl. Now, with the squeeze through the Guardsmen ahead of me tightening, I slowed even more. I heard myself letting out an anticipatory holler, like a Hollywood fighter pilot banking through a dogfight, and threaded the needle at nine miles an hour.

There are more than 8,000 sequoias in the Giant Forest, the three-and-a-half-square-mile centerpiece of the park. The largest grow more than 300 feet tall and 30 feet across, barely tapering as they rise until, about two-thirds of the way up, the scrambling madness of their branches starts. The branches are crooked and gnarled, while the rest of the tree is stoic and straight. The branches are grayish and brownish — average American tree colors — while the trunk, particularly in sunlight reflected off snow, hums with a dreamy reddish-orange glow. The branches often seem to have nothing to do with the sequoia they’re attached to; they are trees themselves. In 1978, a branch broke off a sequoia called the General Sherman. It was 150 feet long and nearly seven feet thick. All by itself, that branch would have been one of the tallest trees east of the Mississippi.

The General Sherman Tree is one of the park’s primary attractions. It’s 275 feet tall, 100 feet in circumference, and known to be the largest tree on Earth, by volume. (The National Park Service drives home its massiveness on a sign in front of its trunk this way: If the General Sherman were hollowed out and filled with water, it’d be enough water for you to take a bath every day for 27 years.) The General Sherman is not far off the Generals Highway, which runs through the park. It is a tree with its own parking lot. Though the pathways were ice-crusted or snowed under when I visited last month, I watched tourists of all shapes and sizes hobble and skitter over them toward the tree for photographs: the Italian dude with the soul patch posing with double thumbs up; the overweight couple huffing, “You make it to the tree?” to a few young women returning to their car; the young man looking up at the tree, eyes closed and still, face in the sun — a tranquil image of cosmic, momentary oneness were it not for his self-aggrandizing sweatshirt, which read, I AM NOT A GOD BUT SOMETHING SIMILAR. And then there was the woman with a moaning child in her arms. She was whispering, “Last one, I promise,” while her husband set up a tripod and timer, far, far away, struggling to frame his teensy family against the universe of the tree. Eventually the man found he had to reposition and walked right in front of me. When we made eye contact, he said, “It’s big!”

Exactly, yes. And still, it’s not just that the trees are big; it’s that everything about them is also big. The raised columns of bark running down their trunks are bigger than the bark on ordinary trees. The gullies between those columns are wider and deeper. The fire scars are bigger. (Sequoias are mostly fire-resistant, even when wildfires or lightning burn away at their bases, opening triangular, vaulting caverns in their trunks, like grottos in a sea cliff.) The burls on the trees are bigger. Even the woodpecker holes are bigger, which seems illogical — you’d expect woodpeckers to hammer out the same size holes, regardless — but honestly, they are. Every element of a sequoia is freakishly, but also flawlessly, proportionally big. And this creates a subconscious sense that you’re not looking at a normal tree that just kept growing until it became very tall but a tree that was somehow supernaturally inflated to unimaginable dimensions, all of its features swelling like some fantastically transformed mushroom or a cursed cartoon man bloating into a giant. This aspect of the sequoia’s size is also a tricky thing to pick up from photographs. Even if there’s a fence or person in the shot for scale, the human eye can find a way to correct for the sequoias’ unacceptable gigantism: It reads the fir trees near the sequoias as bushes, to make the sequoias seem like ordinary trees; or it flattens the perspective, so that, say, four far-off sequoias appear to be right alongside six cedars in the foreground — fusing all of them into a single line of 10 perfectly boring-size trees. In one of these ways or another, virtually every sequoia picture I took wound up a dud. Later, when I texted a friend what I thought was the best one, she mistook it for a shot of my backyard.

“I feel like I’m in a fairy tale!” a woman named Angela Fitzpatrick announced one afternoon. Fitzpatrick and I were the only two people who had shown up for a snowshoe hike led by a nonprofit group called the Sequoia Parks Conservancy. The park’s sparse winter crowds heightened the otherworldliness of the trees. So did all the snow. The woods were hushed around us, a cradle of pure whites, reds and greens.

Fitzpatrick was an information-security analyst from Tampa, Fla., who had been flown out to audit a credit union in a nearby town, then planned an extra day to see the trees. She was excellent company, equally not-shy when it came to fumbling expressions of stupefaction and delight. At one point, falling behind, I realized I hadn’t yet touched a sequoia, so I veered off and patted one. “It’s soft!” I shrieked. “What the hell?” (The trees’ outer layer is spongy and fibrous — a defense against burrowing bugs.) “That’s crazy!” Fitzpatrick said. She hustled back to put a hand on the tree. We stood side by side for a second, pressing and kneading it. “I’m so glad you touched that!” she said.

Later we stopped short in front of another sequoia that looked perfectly healthy on one side, but was chewed up by fire on the other, leaving a 150-foot-tall concave husk from ground to crown — a pillar of charcoal. It was shocking: a baleful black chamber the color of new asphalt, or volcanic rock, or Mordor. Deep in, at the rear, I could see another opening, a twisting pit through the mulchy ground toward its roots.

Is that even alive? we asked our guide, Katie Wightman. Of course it was, she said; a tree like this might endure for centuries. Then she asked, “You guys wanna get inside?” We did.

Sequoias, when photographed, defy efforts to maintain a sense of their true size. Note the teeny-tiny sign at bottom right. Credit David Benjamin Sherry for The New York Times

There’s a type of enchantment we feel from afar, for certain places and things, that’s hard to pick apart or defend after years of feeling it. I used to live in San Francisco and had encountered the sequoias’ cousins, the coast redwoods, many times. They were, in my mind, the slightly less spectacular of America’s two spectacularly large tree species: taller than sequoias, in many cases, but plainer — more conventionally treelike and slender, with pinnacled, Christmas-tree tops and duller, browner bark. But mostly they were just more accessible, at least to me. Their range runs from south of Monterey up the coast into Oregon. One of the most famous groves, Muir Woods, was close enough to the city that I once chaperoned my daughter’s preschool field trip there.

Sequoias, on the other hand, existed only at the edges of my personal geography. In all the world, there were only about 70 native groves of them, flecked across a relatively thin stretch of the Sierra, far east of San Francisco and Los Angeles, beyond the Central Valley’s citrus groves and almond fields. It was arbitrary, but I’d lived my life in California predominantly on a north-south axis, road-tripping more often along the coast than inland to the mountains. Redwoods were creatures I ran into from time to time without trying, while sequoias remained effectively hidden. They were the giants I needed to search out and pursue. And this implied something, too, about the alluring enormousness of the world that contained them.

Now I wanted to go see some of the oldest, biggest trees on Earth so I could feel small. The literature of sequoias is, counterintuitively, also a celebration of smallness. There’s a promise of renewal and transcendence in the juxtaposition of self and tree. The ecstatic naturalist John Muir, among the first to go gaga for “King Sequoia,” wrote that “one naturally walked softly and awe-stricken among them … subdued in the general calm, as if in some vast hall pervaded by the deepest sanctities and solemnities that sway human souls.” (Muir also made “wine” by soaking the trees’ cones in water and drank it as a “sacrament.” He wrote, “I wish I were so drunk and Sequoical that I could preach the green brown woods to all the juiceless world.”)

It seemed like a particularly good moment in America for humility, for perspective-taking, for recalibrating my sense of scale and time. But the night before I was supposed to fly out, a snowstorm unexpectedly hit the Sierra, provoking a long and brutally disincentivizing warning on the National Park Service’s website. “Roads may close,” it said, and tire chains were now mandatory — equipment I’d always found irrationally intimidating, even more so, perhaps, than the prospect of skidding off a mountainside. The alert concluded: “If you’re uncomfortable driving in the mountains during winter storms, consider postponing your visit.”

I suppose it was typical winter-mountain stuff. But in my inexperience, I panicked. And I continued panicking until I eventually reached the park — a day later than I had planned, after deciding to indulge that panic and spend a night at the base of the mountain, betting the roads would at least partly thaw in the morning. “Snow panic,” a friend called it, a friend who had been considering meeting me in the sequoias and was now bowing out. It was a familiar strain of jittery duress and intensifying fragility that comes from trying with all your energy to figure out exactly how bad the future will be.

In retrospect, I recognize that the weather was just one more uncertainty — and one too many — to withstand; already, I worried that a strange-but-minor injury on the ball of my foot might become inflamed and keep me from hiking around the park, and that a scratch in my throat was the beginnings of my daughter’s flu. And beneath the foot and the flu were other worries — namely, about the recklessly accelerating gush of world events that I’d been pummeling myself with many times an hour online. All it took was returning after a few hours away from Twitter to discover a long record of outrages stacked up and hardened like signs of ancient droughts or fires preserved in the rings of a tree. The timeline was quickening, tightening; there were certain days on which we’d all lived through centuries. When I called William C. Tweed, a former ranger at the park, he told me, “On a good day, the sequoias remind us that we’re not really in charge of the world.” I wanted that. But the snow was a reminder that not being in charge also means being powerless. That kind of smallness didn’t feel liberating at all. I hated it.

Sequoia National Park was established in 1890, at a moment in America not so wildly different from our own. It was an era of intensifying inequality, vulnerability and dislocation. Urban industrialization upended rural tradition, and populist uprisings, like the Pullman Strike and the Haymarket Riot, pitted an exasperated working class against a government that seemed to collude with the corporations exploiting it. As a labor leader in San Francisco named James Martin wrote, with society seemingly in “chaotic condition, there is ample scope for the most dismal speculation.” And so, in 1885, a collective of radicals, including Martin, decided to build an alternate society, applying to purchase government land in the Sierra where they could construct a glimmering socialist utopia. Kaweah Colony, they called it. Fifty-three individuals filed claims for 8,000 adjoining acres, centered in the Giant Forest.

American settlers had been enraptured by the giant sequoias since they first stumbled onto them 30 years earlier, and yet the government had never seen any reason to protect the land; in fact, the federal Timber and Stone Act, under which the Kaweah colonists were purchasing their acreage, was meant to encourage logging in the West. And this was the colonists’ plan: They’d be lumberjacks, bankrolling their utopia with that enormous storehouse of wood. All they had to do was build a road in and out of the forest — 20 grueling miles straight up a mountainside pocked with jagged eruptions of granite. A tremendous job, but doable, they decided. They were optimists, after all.

By the end of the following year, there were 160 Kaweah colonists on site, throwing themselves at the road-cutting project and establishing the structures of their new civic life. The colonists split into “divisions,” then subdivided the divisions into hundreds of different “departments,” like a Hand-Craft Department and an Amusements Department. They exchanged man-hours as currency and got a lot done; Kaweah quickly turned into an egalitarian cooperative. “Brute passions,” Martin reported, were “surrendering to moral restraint,” and an “inoffensive and charming rivalry exists to outdo the other in neighborly acts.” Colonists picnicked together, dried fruit, sewed clothes and never spanked their children. One photo shows dozens of them posing in front of one phenomenally large sequoia — a tree so unmistakably magnificent they named it the Karl Marx Tree.

By the summer of 1890, the colonists had pushed their road within a few miles of the sequoias. They decided to pause there and start felling pine trees, to scratch together the money they needed to finish. But that fall, Congress created Sequoia National Park, only the second in what would become America’s national park system. The government didn’t try to seize private land for the park; in this case, the Kaweah colonists didn’t technically own the acreage. Their application to buy it had never been officially approved. Only private citizens were allowed to purchase land under the Timber and Stone Act, and because all 53 original Kaweah claimants had used the same San Francisco address on their paperwork, officials had flagged it, suspecting they were a large and devious corporation. (Logging companies were, in fact, grossly abusing the law, coordinating groups of locals — sometimes just by buying rounds at the local saloon — to claim chunks of land on their behalf.) The colonists were aware of this bureaucratic hiccup, but had gone ahead, expecting it would eventually be resolved. In the end, it wasn’t. They were stripped of the land, and the government claimed the road they built as well. Several members were charged with federal “timber trespass.” America renamed the Karl Marx Tree after General Sherman.

Historians now see evidence that the government’s actions were influenced by the Southern Pacific Railroad, which was moving to protect its own interests in the area. That is, the Kaweah colonists spent four years working as unpaid labor on a nightmarish infrastructure project to improve land for the same exploitative governmental-industrial complex from which they thought they were breaking free. They had tried to resize themselves — to create a smaller, separate and more perfect world in which their lives and values could be bigger — but the real world was still all around them, and in it, they were still painfully, negligibly small.

It’s hard to diagram the Kaweah story as an allegory of any contemporary ideology of good and evil, heroism and villainy. It gets confusing: The federal government, partly at the behest of an underhanded corporation, sabotaged a community of hardworking and benevolent utopians — but only to create something fundamentally idealistic and to protect an irreplaceable ecological wonder from capitalistic loggers. And yet, the loggers were the utopians. The capitalists were socialists! Which would have been fine, except that the government had mistaken them for an underhanded corporation.

Baffled, I called William Tweed, the retired Sequoia park ranger, who has also written about the colony. “You reach a stage in life where what you most frequently see in history is irony,” Tweed told me sagely. “Perhaps the lesson for 2017 is that ideology rarely explains what happens.”

The General Sherman Tree, 275 feet tall, 100 feet around. Credit David Benjamin Sherry for The New York Times

It was almost dusk on the first evening by the time I rented my Fiat at the San Jose airport and reached the entrance to Sequoia National Park. I pulled into the tiny outpost of Three Rivers, Calif., and headed straight to a place called the Totem Market to rent a set of tire chains, still toying with the idea of pushing up the mountain that night.

The market is a combination gift shop, bar, deli and full-service tire-chain-rental depot — a sleepy-seeming establishment with wagon wheels and barrels on its roof. But inside, the scene was incongruously lively. A couple dozen mostly younger people stood around the bar, shouting conversation over that song that goes “Amber is the color of my energy” again and again. It felt like a rehearsal dinner; I couldn’t figure out how everyone knew one another. Then a woman in full Park Service garb — green wool pants, khaki shirt, government-issue leather boots — stepped out of my peripheral vision to order a beer.

Almost all of them were “parkies,” as one man eventually put it. They were giving a going-away party for one of their supervisors, who was leaving for a new detail at a park near San Diego. Someone pointed him out: an older, smiley, muscular man in a T-shirt that said, “Yard Sale.” They eventually sang “Happy Birthday” to someone, too — a younger guy in a camouflage hat, holding a generous glass of red wine lazily aloft and squinting. At one point, another man dropped a pint, and it shattered. The entire room shouted and applauded. Then Yard Sale graciously, dutifully appeared with a broom and — maybe, I wanted to imagine, just to leave his troops with one final image of how a true leader behaved — swept up the glass.

Off in a corner, I struck up a conversation with Thor Riksheim, a tree-size Park Service veteran with an impressive mustache. Riksheim directs historical preservation at Sequoia. He had recently restored the only Kaweah Colony building remaining in the park, a remote cabin that the government calls, a little ruthlessly, Squatter’s Cabin. The colony had been conspicuously written out of the official story of Sequoia National Park, and its road has long since reverted to a trail. But Riksheim spoke affectionately of the cabin, which he called “Squatty’s,” and the colonists, too. (He also called the General Sherman Tree “Sherm,” as if they’d gone to high school together.) Right away, I liked him immensely. It was clear his connection to the trees was deep and singular. He was currently living in another historic building he had restored in the heart of the Giant Forest — in the shadow of the famed Sentinel Tree, a cluster known as the Bachelor and the Three Graces and other sequoias. It was touching how privileged he seemed to feel, how proud. “I’m Giant Forest, population 1,” he told me.

To a human being, a 2,000-year-old sequoia seems immortal. But I noticed that people like Riksheim who have lived closely with the trees aren’t prone to mistaking their longevity and resilience for indestructibility. To know sequoias means being cognizant of their weaknesses, understanding them as provisional objects in some vaster, slower-moving natural flux. In fact, there’s a prominent exhibit at the park’s Giant Forest Museum chronicling how the government nearly undid the trees’ entire ecosystem through misunderstandings and mismanagement. By the 1930s, the Park Service had constructed a small resort town for tourists in the center of Giant Forest. There were restaurants, cabins, a gas station, a hotel and a grocery store — nearly 300 buildings, erected over the sensitive and shallow root systems of the sequoias, which never reach more than about six feet below the surface. The Park Service vigilantly fought back the beginnings of forest fires; this seemed wise, fire being a reckless and destructive force, but it actually kept the sequoias from reproducing. (It was not yet understood that, among other ecological benefits, heat from wildfires opens the trees’ cones and allows them to spread their seeds.)

All of this was gradually corrected. Then droughts started intensifying. The climate was shifting. The Park Service is now contemplating “assisted migration” of the sequoias: manually planting them farther north to keep pace with climate change. But of course, Tweed, told me, it’s now conceivable that the Trump administration might not allow climate change even to be mentioned at national parks’ visitor centers. Or that the administration, which picked a Twitter fight with the National Park Service on Day 1, might decide to privatize management of those lands. Who knows, Tweed said: “The worries are deep and profound.”

That is, there is another time scale on which the trees are vulnerable, on which the trees are small and come and go as we do: sprouting, growing up, suffering through storms, receiving scars, losing limbs, before they finally drop. Every so often, the imperceptible turbulence and instability in which the trees exist does upend them. Apparently, the first thing you hear when one is falling is a blistering and percussive crackle — the roots snapping, one at a time, underground. It may be far less likely, at any given moment, that one of the sequoias in the park will keel over than that one of the tourists will, but it could happen. It must happen, every now and again. Earlier this year, a famous sequoia with a road tunneled through its base, known as the Pioneer Cabin Tree, farther north, near Sacramento, toppled over in a storm. At the Giant Forest Museum, I saw photos of another one that flattened a parked Jeep in August 2003.

The canopy in Sequoia National Park, where the branches are large enough to be impressive trees in their own right. Credit David Benjamin Sherry for The New York Times

I don’t know why, but I could not stop thinking about this while trundling around the park that weekend: I kept privately picturing them cracking and crashing down. It was a tremendously upsetting image, but still never felt possible enough to scare me.

Late one afternoon, I lay down in the snow at the base of one for a while, watching as the fog poured in through its crown, and I remembered how untroubled Riksheim sounded at the bar the previous evening when, lowering his voice, he mentioned that there was a particular sequoia near his house that he was keeping an eye on. He could wake up dead tomorrow, he said. “It’s just that flying, fickle finger of Fate. Every once in a while, it’s going to point at you.” Then he fluttered his long, bony index finger through the air and lowered it with a sudden whoosh. Out of nowhere: crash. And I realized that his experience of it — a feeling of forsakenness, of arbitrary cruelty — would be essentially the same as the tree’s.

Two days later, I was snowshoeing around alone when I discovered I was standing in front of the same sequoia I had lain under. There, in the sloping snow at its roots, I saw my imprint. My back and legs and arms were joined into a wispy column, with the perfectly ovular hood of my parka rounding off the top. It looked like a snow angel, but also like a mummy — an image of both levity and dolefulness, neither all good nor all bad. I took a picture of it: what little of myself was left after I’d gone. The figure looked smaller and more delicate than I thought it should, but the Giant Forest was so quiet that I couldn’t imagine who else it could be.