- Source: i-D

- Author: Sara Radin

- Date: March 13, 2019

- Format: DIGITAL

Honouring Robert Mapplethorpe’s Unexpected Images

Thirty years after his death, the Guggenheim hosts back to back exhibitions to celebrate the beloved artist's work, from floral still life to documenting New York's S&M scene.

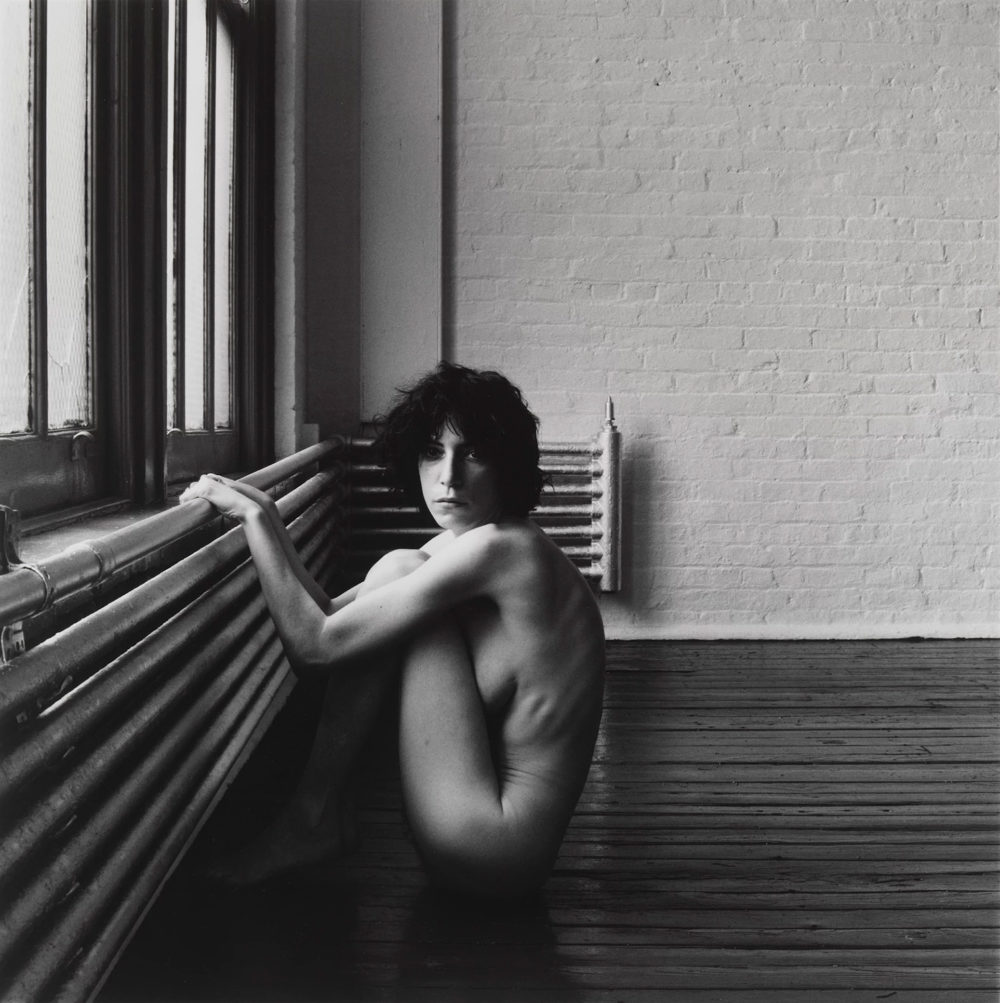

On the dedication page of Patti Smith’s 2010 memoir Just Kids, she honors her dear friend and former lover Robert Mapplethorpe, writing, “He will be condemned and adored… [but] in the end the truth will be found in his work, the corporeal body of the artist.” Thirty years after the artist’s death due to complications from AIDS on March 9, 1989, Mapplethorpe’s photography is still a compelling view into the expansiveness of the queer experience.

Born in 1946 into a large Roman Catholic family in Queens, New York, Mapplethorpe, went onto attend Pratt Institute in Brooklyn for college in the mid-to-late 1960s. There, he explored the mediums of drawing, painting, and sculpture, ultimately trying his hand at making mixed media collages before dropping out of school. Finding inspiration in the work of artists such as Joseph Cornell and Marcel Duchamp, he eventually began cutting and pasting images of men from books and pornographic magazines, combining them with found objects and paint.

According to the Guggenheim, while it was not the artist’s intention to be a photographer, Mapplethorpe decided to create his own images for these works in 1970 and thus began experimenting with a Polaroid SX-70 and later a Hasselblad, which were both given to him by friends. Drawn to the medium’s immediacy, he soon came to recognize that, “photography maybe could be art.” His experimentation with art making and photography as a means to document the fringes of society paralleled his own exploration into the confines of his sexuality.

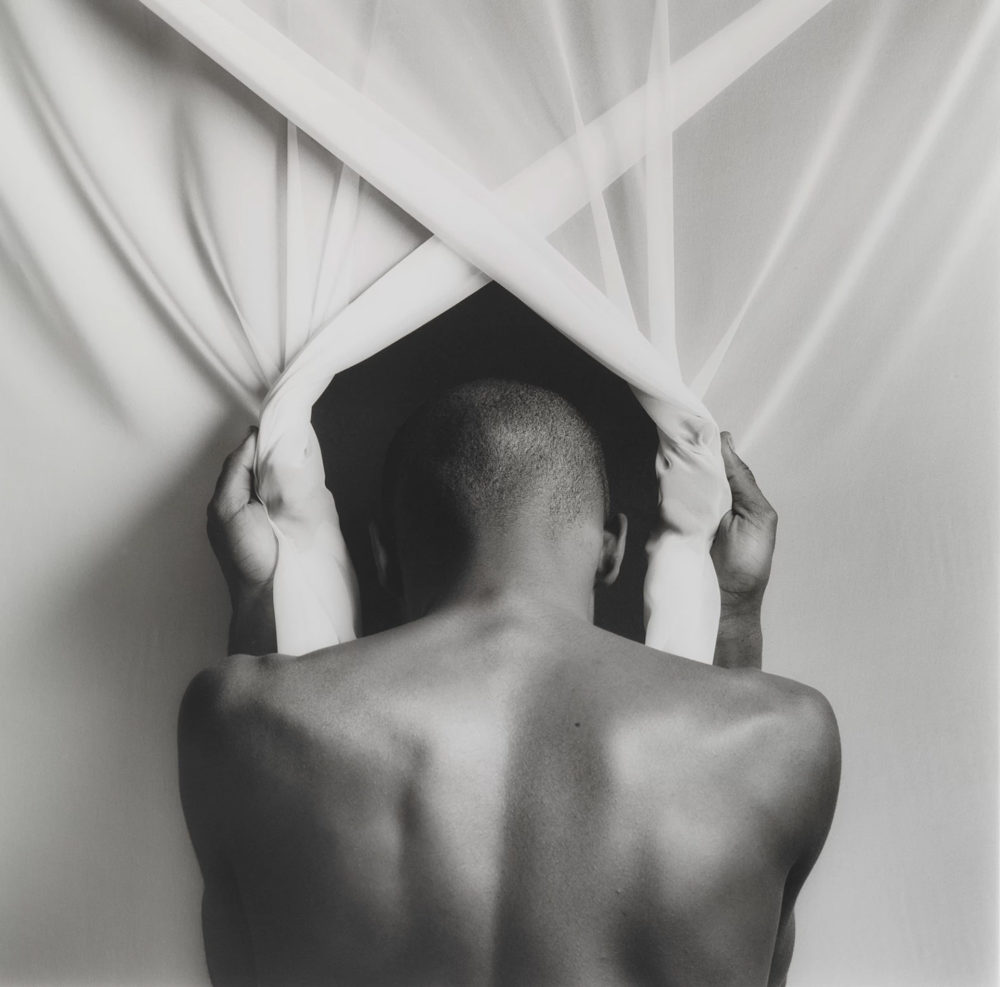

Photo by Robert Mapplethorpe. Phillip Prioleau, 1982 Gelatin silver print, 38.4 x 38.9 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Gift, The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation 96.4362

© Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission.

It was in the late 1970s that Mapplethorpe became most interested in documenting the S&M scene of New York — work that was considered shocking at the time for its erotic subject matter. In these images, Mapplethorpe created stylized and meticulous compositions of the human body, which focused on its seductive nature and inherent beauty. As a participant in the city’s downtown gay bondage scene and a keen observer, the artist felt an obligation to archive life as it was unfolding before him. Mapplethorpe told ARTnews in 1998, “I don’t like that particular word ‘shocking.’ I’m looking for the unexpected. I’m looking for things I’ve never seen before … I was in a position to take those pictures.” While in Catholicism homosexuality was considered a mortal sin, Mapplethorpe used the practice of photography to elevate the body as a perfect object worthy of its own form of devotion.

Though the artist has become well-known for his more outwardly provocative imagery that was created before the proliferation of pornography and social media, it is worth taking a closer look at his floral still lifes, a subject he explored throughout his career, which seem to mirror the sensuality of his nude portraits. According to Phaidon, who released a book of Mapplethorpe’s floral series in 2016, Jack Fritscher, a writer, publisher and one of Mapplethorpe’s lovers, is said to have called his images “holy pictures,” believing that the flowers represented “night-blooming sex organs.”

In these images, portraits of individual and groups of poppies, calla lilies, and tulips were shot with stark lighting, emphasizing the twisting of their stems and the curves of their petals while also illuminating their carpels and stamens, which are the male and female parts of a flower.

Photo by Robert Mapplethorpe. Calla Lily, 1986 Gelatin silver print, 48.9 x 49.1 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Gift, The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation 93.4302

© Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission.

While an innocent bystander unfamiliar with Mapplethorpe’s typically subversive work might see these portraits as merely simplistic images of flowers, they are innately erotic objects as flowers are actually the sexual organs of plants. In fact, Fenton Bailey, the co-director of HBO’s 2016 documentary, Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures, says that historically flowers have often been used to represent gayness in a negative sense, such as aesthetes and sunflowers, “but Mapplethorpe revealed and celebrated their carnal nature.”

According to Fenton, at the time of these creations, secret coding was not only common but also a necessity for underground gay culture. “The wink is simply that the conservative collector with a flower picture in his living room might actually have a hidden, edgier side,” he says. Thus, for Mapplethorpe, every pistil and stamen was a way of “signaling horny homosexual desire” without revealing a thing. In these images, Mapplethorpe’s sexuality was hiding in plain sight.

“Mapplethorpe’s flowers, like all of his subjects, are invested with the power of eros,” says Guggenheim’s Lauren Hinkson, Associate Curator, Collections, and Susan Thompson, Associate Curator, with Levi Prombaum, Curatorial Assistant, Collections. In this way, the artist invested each floral image with a dose of “overt sensuality and latent desire.” The photographer once said, “my approach to photographing a flower is not much different than photographing a cock. Basically, it’s the same thing.… It’s the same vision.”

But more than this, flowers represent the natural cadence of human life. Withering and dying in a rather short time period, Fenton also sees the flowers as self-portraits of Mapplethorpe, “an artist who would blossom for only a brief period before dying soon after.” Thus, there’s a melancholic element to this series, as they seem to simultaneously celebrate and memorialize the breadth of Mapplethorpe’s artistic practice and complex identity in the face of his death, which was due to a highly stigmatized illness that took his life and that of many other members of the queer community in the 1980s.

Photo by Robert Mapplethorpe. Patti Smith, 1976 Gelatin silver print, 35.2 x 34.9 cm

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Gift, The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation 96.4362

© Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission.

Yet for Mapplethorpe, bodies and flowers were one in the same — a means of capturing the beauty of humanity, which when paired together would create a “nuclear fission and a cultural freak-out that would secure his mortality,” says Fenton.

Creating his own cultural legacy as he lived, Mapplethorpe made a point to create his own foundation before he died to keep his work in circulation and his name alive. His life’s work is also currently the subject of two back-to-back exhibitions at the Guggenheim, Implicit Tensions: Mapplethorpe Now , taking place January 25–July 10, 2019 and July 24, 2019–January 5, 2020, which aim to showcase the spectrum of the cultural icon’s work.

While Mapplethorpe is honored as a cultural figure and a queer icon who pushed the boundaries of photography and brought visibility to the gay community during the post-Stonewall era of sexual liberation, his work remains incredibly relevant today, especially in a time queer media is more common, yet sexual censorship is pervasive. Still, Fenton believes, “He would have loved Instagram, although he would’ve probably been continually banned.”