- Source: THE NEW YORK TIMES

- Author: RANDY KENNEDY

- Date: JANUARY 28, 2009

- Format: DIGITAL

His Nonlinear Reality, and Welcome to It

MIAMI

THE shoot the night before had lasted into the next day, ending around 9 a.m. after a scene in which the perimeter of the kidney-shaped swimming pool had been set ablaze with rubbing alcohol. So when the artist Ryan Trecartin greeted a visitor that afternoon, sleepless for more than 24 hours, he ran his hands through his hair and said, “This really isn’t me.”

He meant that he wouldn’t be much good for an interview. But he could just as well have been speaking in the voice of one of the maniacally mutable characters he plays in the videos he has been writing and directing for the last several years, characters whose hold on identity and existence itself seems so tenuous that they must keep talking to keep from disappearing. (“If I didn’t take the liberties to glue these prop knobs onto my safe space, who would you think that I’d be?” demands one, in what has become Mr. Trecartin’s signature unhinged vernacular: phrases that sound like something you might have heard before, on television or the Web, but haven’t.)

Mr. Trecartin (pronounced tra-KAR-tun) was creating these characters more or less for himself and a band of friends and collaborators from the Rhode Island School of Design when one of his works, posted on his Friendster page, was seen in 2005 by the artist Sue de Beer, who brought it to the attention of a curator at the New Museum in Manhattan. In stunningly short order, even for an art world then still moving at breakneck speed, his work was everywhere: the 2006 Whitney Biennial, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the Saatchi Gallery in London, the collection of the Guggenheim Museum. And his most ambitious work to date, the movie-length “I-Be Area,” which made its debut in 2007 at the Elizabeth Dee Gallery in Chelsea, was greeted with a kind of joyous critical consensus rarely seen in the art world.

Mr. Trecartin, a friendly, loquacious, boyish-looking man who grew up in a steel-mill family in rural Ohio and who counts the Disney Channel and “Dirty Dancing” among his important artistic inspirations, was only 26 years old.

So there has been a lot of anticipation about what he will come up with next. And for the last five months Mr. Trecartin, now 28, has been working long hours to meet it in a slightly ramshackle Spanish-mission-style house on the edge of the Little Haiti neighborhood here that he has rented for $2,000 a month and that serves as set, dormitory, editing suite, sculpture studio and site of a kind of continuous happening. The work that emerges conceived now as a trilogy, two parts video and the third a performance will take him back to the institution that helped discover him, the New Museum, where the video portions will be a key part of “Younger Than Jesus,” the museum’s first installment of a new triennial that will focus on the work of artists under 33, opening on April 8.

The raw material for Mr. Trecartin’s new work is what is happening to the world economy as financial institutions implode and the mechanisms of capitalism and credit falter. So the house he has adopted as his temporary home is fitting: it is near the city’s Design District, which has become an art-world hot spot in recent years, but in a rapidly changing middle-class neighborhood now dotted with foreclosure signs amid the crabgrass.

Even the reason he came to Miami plays well into his story line about transition. He originally arrived to make a smaller project at the request of the nonprofit Moore Space here, founded by the prominent collectors Rosa de la Cruz and Craig Robins, but they closed the space unexpectedly in October, in an example of the reordering that is beginning to unfold in the art world.

So with help from his gallery, collectors, the New Museum, the Moore Space and several of his own beleaguered credit cards, he rented the house and began making sets and costumes with his friend and closest collaborator, Lizzie Fitch, and others. As filming began, he welcomed a steady stream of friends and regulars, along with professional actors considerably more than he has used before, drawn partly from the child and teenage performers in Orlando, home of Walt Disney World and Universal Studios.

When a reporter arrived at the house the day after the all-night shoot, Ms. Fitch was still asleep in the pool house, and the sun-splashed backyard was strewn with what looked like the aftermath of a small riot or a ritual for a new Day-Glo religion. Bricks lay everywhere around a brightly colored prop wall. Lifelike models of tiny purse dogs were scattered in the weeds. A white metal bed frame from Ikea was submerged in the pool. (Ikea and Target are the main sources of furniture and props for the project because of their ubiquity and faux-designery corporate blandness, Mr. Trecartin said.) Above the pool was a wooden armature rigged with a pulley that had been used to lower the artist into the water the night before, a deus ex machina in canary yellow shorts.

Ryan Trecartin is working on a trilogy, two parts video and one part performance, inspired by the state of the economy.

Moris Moreno for The New York Times

Asked how the neighbors reacted to such doings, he said that the house on one side was boarded up and occupied by squatters whom few people had seen. The eaves and roof of the large house on the other side are covered with security cameras, like vultures. No one is quite sure what its residents do.

“There’s a lot of really weird things going on at our house,” Mr. Trecartin said. “But those guys have these huge parties and actually make more noise, so they don’t complain.”

The shoots and plots have grown substantially more complex since his days in Rhode Island and later, with many members of his group, in New Orleans, where they lived until Hurricane Katrina destroyed their house and much of Mr. Trecartin’s work.

In “A Family Finds Entertainment,” the video that brought him to public view, the fairly followable story involves a disturbed and disturbing black-toothed kid named Skippy (played by Mr. Trecartin) who borrows money from his parents, is filmed by a documentary maker, is hit by a car, is filmed by the documentary maker some more as he lies in the road, and whose soul seems to rise from his body when it hears the sounds of a rocking house party.

By “I-Be Area” Mr. Trecartin’s characters had started to serve more as vehicles for his hyperactively interconnected ideas about family, belonging, identity, gender, the Internet and the entertainment industry. But they are much more fascinating than allegorical characters generally have a right to be, with names like Pasta and Jammie, yakking endlessly, arrogantly, pleadingly, in phantasmagoric makeup and crazy clothes. The title character, I-Be, is less a person than an idea of a person waiting to hijack or be hijacked by a personality. (To make things more interesting, I-Be has a clone, and the clone has an online avatar who seems to be mounting a rebellion; the clone and the avatar are both played by Mr. Trecartin in a Southern accent that sounds something like Carroll Baker’s in “Baby Doll,” except on acid.)

In one Web interview Mr. Trecartin helpfully described a chaotic scene in a macabre wood shop near the end of the video as “a conceptual part-cyber-hybrid platform that obeys and functions within both laws of physics and virtual-nonlinear reality and potential in Web 2.0/ultra-wiki communication malfunction liberation flow, add-on and debate presentation.”

In an interview two days after the all-nighter, Mr. Trecartin, with a full night’s sleep, said the new work, as yet unfinished and untitled, was using the dire state of the economy to describe a world in a state of epic, maybe never-ending transition. It is a place where the idea of credit becomes so abstract that “credit cards start to have conceptual agendas” and where people create and use their own currencies. The Web becomes a catalyst for a “postgender world,” said Mr. Trecartin, who is gay. Transvestites would not be the usual kind but instead “astrological trannies” or “personality trannies,” choosing to exist in a state of not quite being one person.

Sitting in his office with Ms. Fitch, the walls behind him covered with circular diagrams that he said helped him keep track of characters, ideas and situations, he tried to describe parts of the numerous plots, which seem to collapse into one another like the perspectives in an Escher drawing.

“This is really hard to describe linearly,” he said at one point. At another, trying to sum up after a long, rambling disquisition, he said, “It’s all just driven by situations in a personality-based system,” causing Ms. Fitch to laugh and double over in her chair, because she has watched him go through these kinds of patient and quite sincere gyrations before.

Massimiliano Gioni, the director of special exhibitions for the New Museum, said he often used the term “hysterical realism” a phrase invented by the critic James Wood to characterize the overly manic language and story lines of fiction by writers like David Foster Wallace and Don DeLillo to describe Mr. Trecartin’s work and that of several other younger artists. But in their art, he said, the hysteria is raised to even more absurd heights, a reflection of the world they have inherited, drowning in information and images.

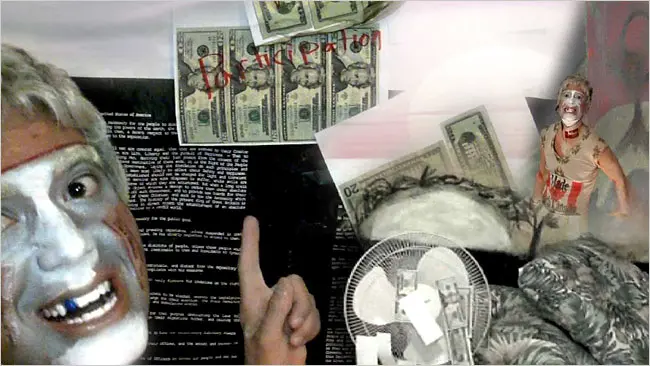

An image from the Mr. Trecartin's upcoming project.

Courtesy of the artist and Elizabeth Dee Gallery

“It’s as if information is speaking the characters rather than the other way around,” Mr. Gioni said.

Lauren Cornell, the executive director of Rhizome (rhizome.org), the online art organization affiliated with the New Museum, said that though it was too limiting to describe Mr. Trecartin’s work as being about life lived largely on and through the Web, “he really captures how the logic of it is becoming embedded in our lives.”

The garish low-budget look and feel of his work, and its near-anarchy, are often compared to early John Waters, to Paul McCarthy, to Mike Kelley and to drag auteurs like Jack Smith and Tom Rubnitz. But when asked, Mr. Trecartin said that he could not think of a work of art, video or otherwise, that had inspired him to want to become an artist. Ms. Cornell said that in long conversations with her in 2007 he told her that when he was first compared to Mr. Waters or to Mr. Smith, he had never heard of them.

“When I was young and my baby sitters came over and turned on music videos, I was inspired by that,” Mr. Trecartin said in his office, where a desk with a large Mac monitor and 10 hard drives shares space with the rumpled mattress he often sleeps on. He said he also reads obsessively, almost completely online, and is feverishly devoted to conspiracy-theory sites and TED Talks, the brainy Web lecture series.

Ms. Fitch interrupted him disapprovingly: “Ryan, I’ve seen you look at a piece of art and be inspired by it.”

Mr. Trecartin responded: “Yeah, but what? I really want to be reminded.”

He said his goal when he begins to write the dialogue in his works, despite seeming ad-libbed, is highly scripted is for viewers to leave his work with a deep emotional response to a reflection of their culture, “but in a way that they really can’t put their finger on why they felt like that.”

While he is ecstatic about his success among curators and collectors, he has an online audience that is just as important to him, one that doesn’t approach his work as art per se. Speaking of an earlier work in an online interview, he once said that if it fared well only among art-world people, “then I’ll feel like a loser.”

But judging from some of the comments on his YouTube channel, he is doing well by his other audience too. “That one hour, 48 minutes was the closest I’d come to someone who could understand me,” wrote a viewer with the screen name Scandibilly after watching “I-Be Area.” “Thank you! Thank you! I understand!”

Although he was born in 1981 into the first home-computer generation, Mr. Trecartin said he thinks that people even younger, who have never known a world without the Web, are the ones who understand his work most intuitively. He told of hiring several teenage actresses for his new video. He tried to explain the ideas for their surreal characters by simplifying them, but it wasn’t working, so he just explained it the way he would have to himself. “And they were like, ‘Oh, yeah, O.K.’ ”

“People born in the ’90s are amazing,” he said excitedly. “I can’t wait until they all start to make art.”