- Source: The Guardian

- Author: Ralf Webb

- Date: October 18, 2021

- Format: Digital

He’s a poet and the FBI know it:

how John Giorno’s Dial-a-Poem alarmed the Feds

After receiving hundreds of thousands of calls, the poet’s project almost broke the New York telephone exchange – leading to an FBI investigation. Will it cause similar chaos in the Instapoet era?

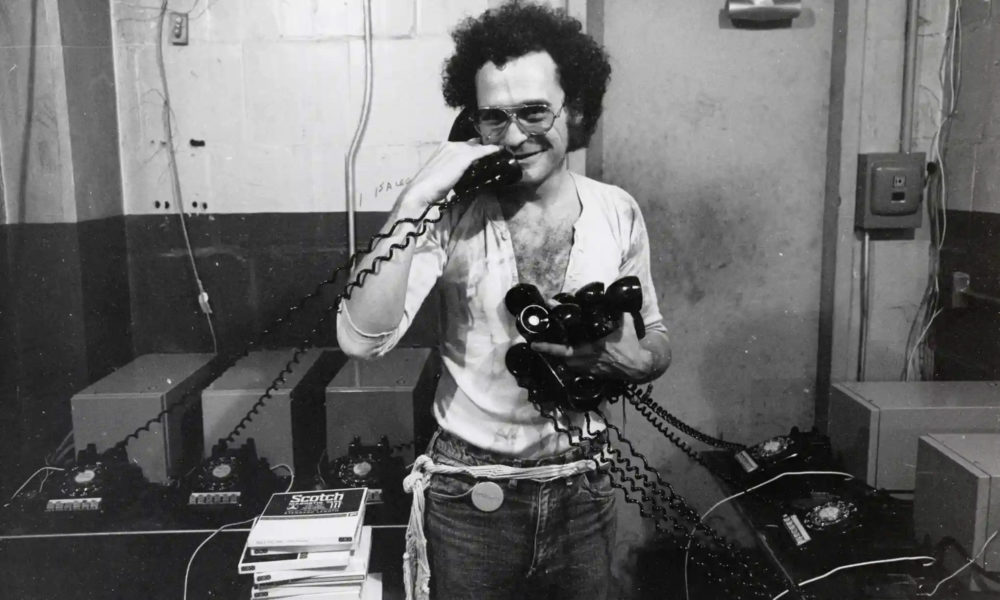

‘A poignant expression of the need and loneliness of people’ … John Giorno's Dial-A-Poem in 1970. Photograph: Studio Rondinone/Courtesy The John Giorno Foundation, New York, NY

In 1968, the poet and visual artist John Giorno was on the telephone when he was hit with an idea. It came to him that “the voice was the poet, the words were the poem, and the telephone was the venue”. He imagined utilising the telephone as a medium of mass communication, in order to generate a new relationship between poet and audience. This would become Dial-a-Poem: one telephone number that anyone could call, 24/7, and listen to a random recorded poem – liberating spoken poetry from what Giorno termed “the sense-deadening lecture hall situation”. As part of New York’s avant garde scene, he quickly enlisted talent, tape-recording the likes of John Ashbery, Bernadette Mayer, Anne Waldman and David Henderson reading poems at 222 Bowery, his loft. He found a project sponsor, 10 answering machines fitted with these recordings were patched together and connected to phone lines and Dial-a-Poem went live.

In 1970, the project moved to MoMA, expanding to host a total of 700 poems by 55 poets – including Black Panther poets and queer erotic poetry. As the project gained press coverage, calls to Dial-a-Poem skyrocketed into the hundreds of thousands, putting immense strain on the Upper East Side telephone exchange. It’s a powerful image – thousands of people who, through some collective desire or curiosity, stretched the project and its public infrastructure to breaking point. Giorno was interested in the pattern of the calls. He imagined bored office workers phoning from their desks, or people tripping on acid, unable to sleep, dialling at 2am. The project’s popularity, for him, was “a poignant expression of the need and loneliness of people”.

As part of the first posthumous exhibition of Giorno’s work in the UK, at Almine Rech, London, Dial-a-Poem is once again live. You can dial-a-poem in situ, at the gallery, using an installed push-button phone. Excitingly, you can also dial from your own phone/device, for free, 24 hours a day: poems on-demand, without a subscription fee. The phone number is +44 (0)20 4538 8429.

Rhyme hotline … Dial-a-Poem had received more than a million calls by the time it lost its funding.

Photograph: Studio Rondinone/Courtesy The John Giorno Foundation, New York, NY

I first dialed while walking around the park, in a leather jacket, in the rain. One of Giorno’s own poems played down the line. He read: “Big fat raindrops bejewelled with radioactivity soaked into this black leather jacket.” It was a thrilling, uniquely poetic moment of synchronicity – and I was hooked. I called while in the supermarket and got Denise Levertov. I called while brushing my teeth, and got Tom Weatherly. Dialling a poem is a weirdly intimate experience – vaguely voyeuristic, clandestine, as if the poets are directly addressing you, to confess, shock or enlighten, while you remain anonymous.

Ilya Kaminsky has said that a great poet speaks privately to many people at the same time. In this sense, poetry is a private language, shared. Does such an exchange benefit from – even necessitate – intimacy? Recent poetry projects have probed this idea: Amy Key’s Poets in Bed podcast (an “ongoing experiment in intimacy”) features contemporary poets reading work from beneath their own duvets. In 2014, the New York-based Alex Dimitrov launched Night Call, a performance project for which he read his poems to strangers in their beds, proposing that to be in a person’s space is “often more intimate than sleeping with them”.

Can social media, our current means of mass communication, facilitate such an intimate poet-audience exchange on a larger scale? Instapoets such as Rupi Kaur and Atticus have amassed millions of followers by sharing their poetry on social media platforms. These poets use those same platforms to sell merchandise – “ergonomic” brass pens, jewellery, magnetic poetry sets. As a result, their work reads like a successful amalgamation of poetry and advertisement. This suits the medium; it could be argued that social media functions more effectively as a marketplace than a means of truly connecting with others. Participating in social media is inherently transactional: in exchange for access, we are constantly (by degrees unknowingly, tacitly or willingly) trading away our privacy – our geolocation, browsing habits, contacts – so that companies can more effectively advertise to us, and we become more productive consumers.

It seems difficult to generate the conditions for intimacy in such a compromised setting. During lockdown, however, there was a proliferation of poetry events held on video conferencing apps. Their relatively democratised nature (many were free, anyone could join, regardless of location) sparked overdue conversations in the literary world about how accessibility is often overlooked at physical venues, and the London-centricity of the scene.

At these online events, during and after a poet’s reading, heart emojis would bloom in the chat-box – an expression of audience appreciation that, being spontaneous and non-obligatory, often felt more authentic than IRL applause, while harking back to naive, less mediated and commodified forms of online communication (remember MSN Messenger?) But there was IRL applause, too: at an event’s close, audiences would be invited to turn on their mics and cameras, and clap. You’d briefly glimpse people in their homes; alone or with lovers; eating, smoking; illuminated by the screen, sometimes by candlelight – visual testimony to the private-yet-shared exchange between poet and audience we’d taken part in.

Dial-a-Poem received more than a million calls before it lost funding and ended in 1971. There were complaints of indecency, claims that the poems incited violence. The FBI investigated, and, in Giorno’s words – an observation that seems to prove Dial-a-Poem’s cultural worth – “the trustees [were] beginning to freak out”. Afterwards, Giorno produced a series of LPs featuring the Dial-a-Poets. In the liner notes of one, he wrote: “We used the telephone for poetry. They used it to spy on you”, referencing the not-unfounded surveillance paranoia of the Watergate era. It’s tongue-in-cheek, but reminds us of the vulnerability and value of intimate and unmediated exchanges between artist and audience.