Installation view

I is Someone Else, 2020

Photograph courtesy of Morán Morán

David Wojnarowicz I is Someone Else

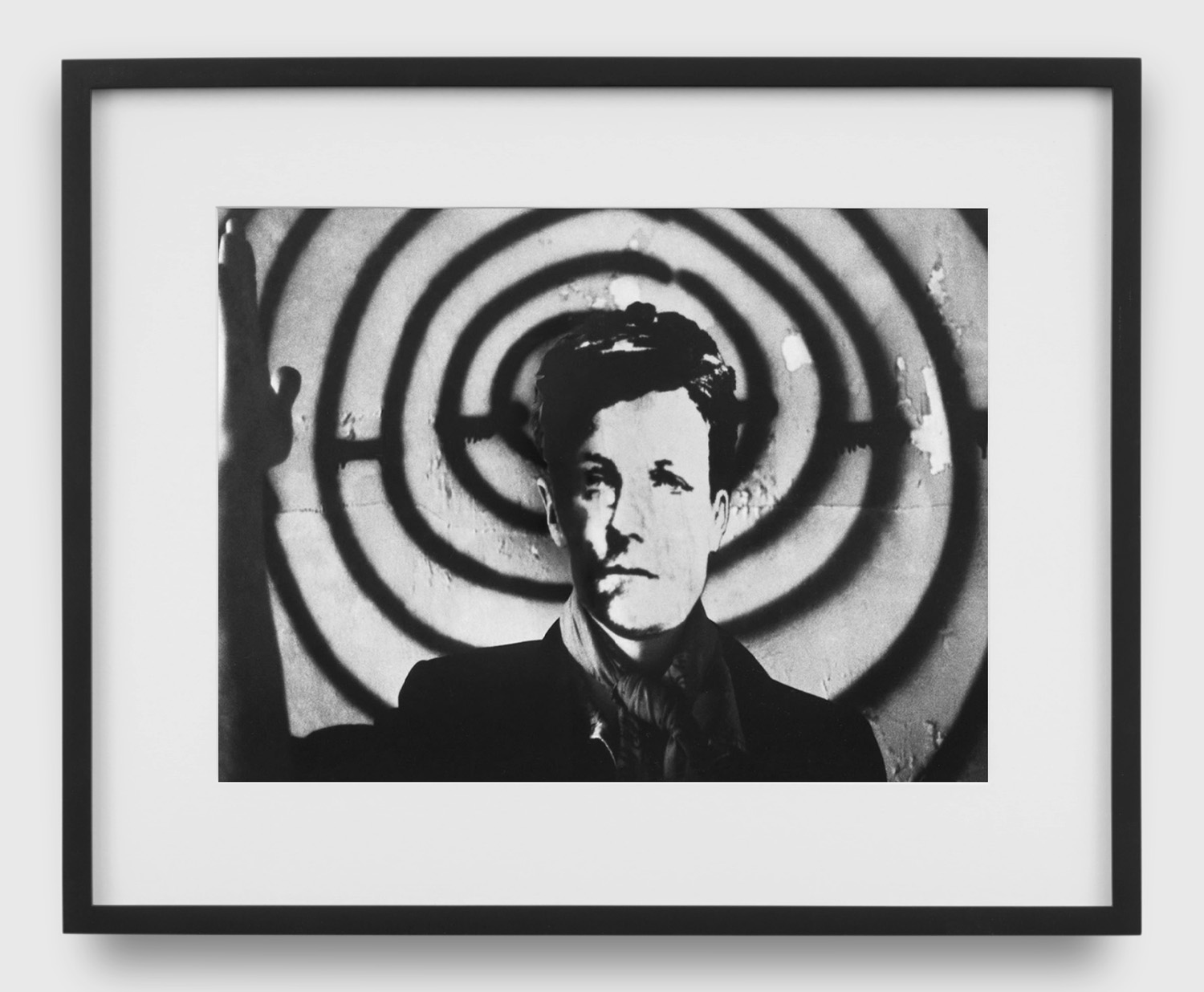

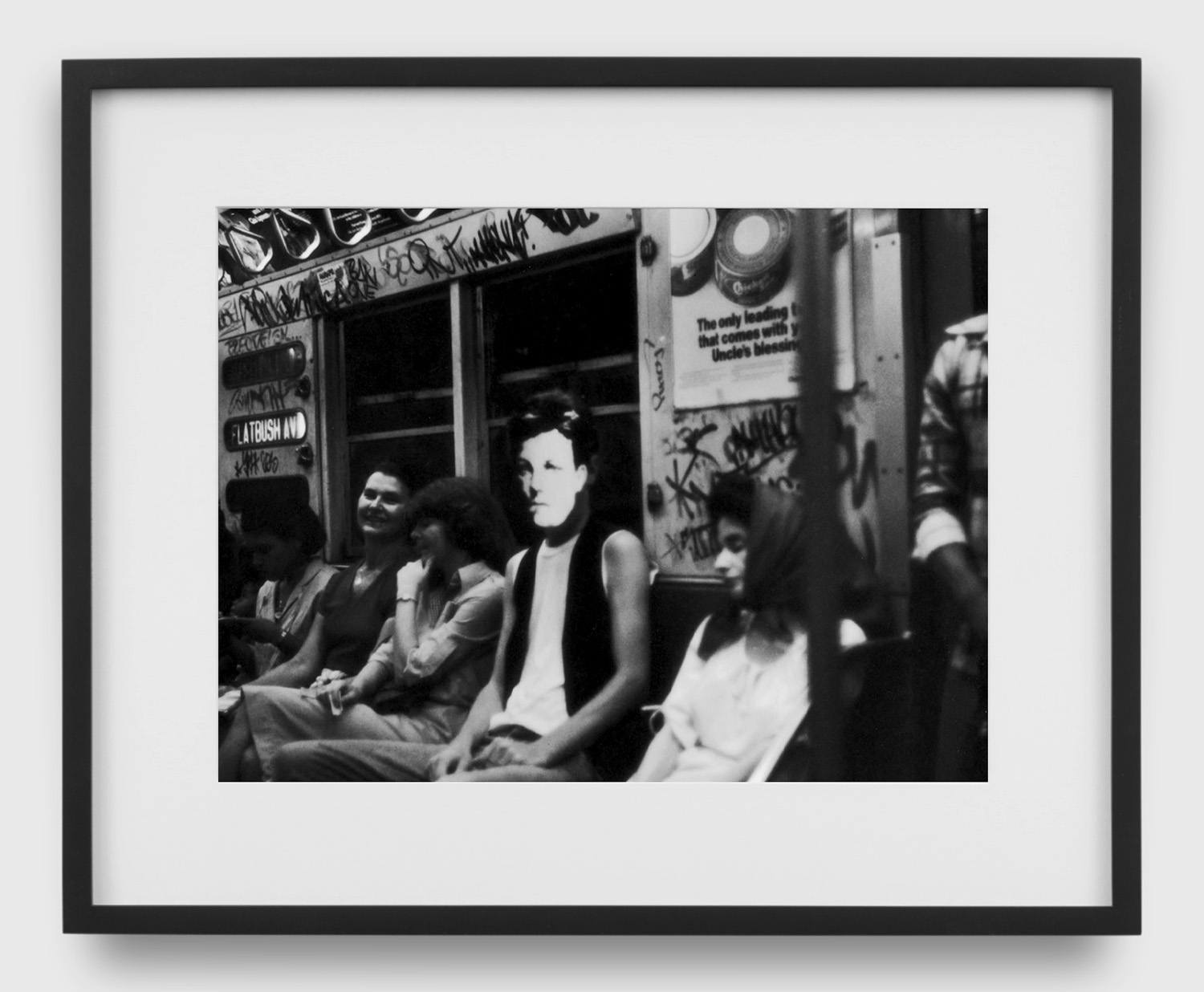

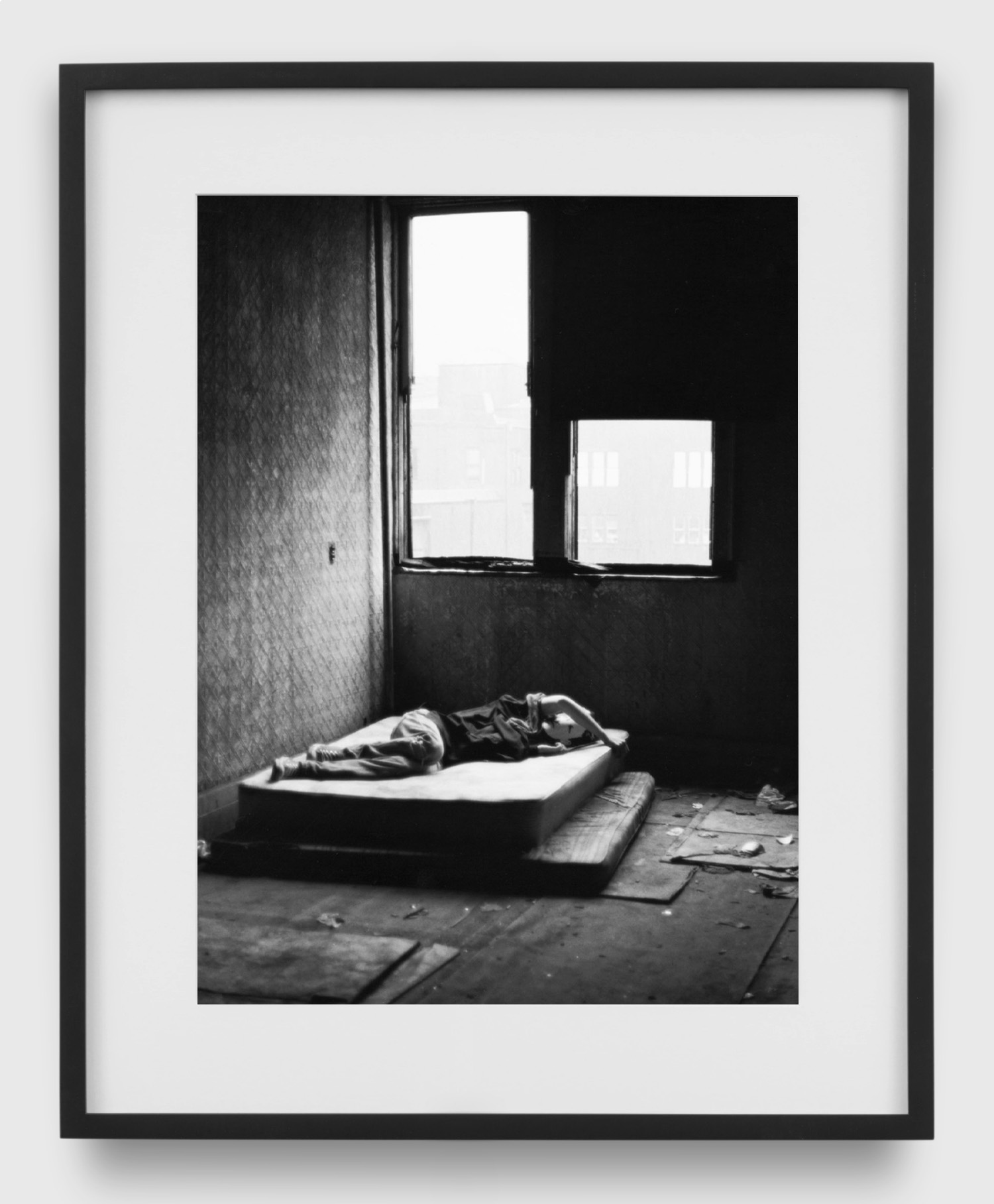

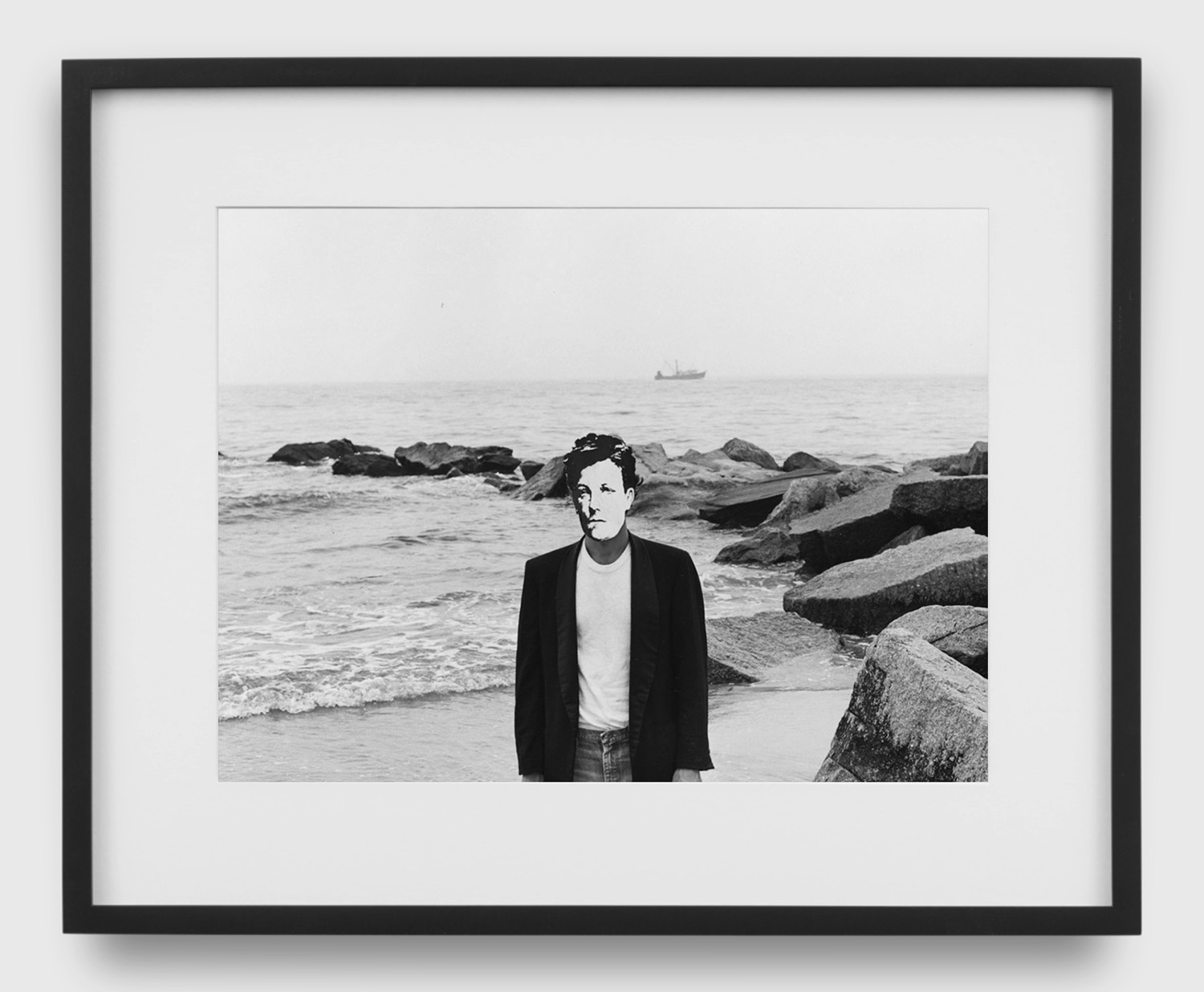

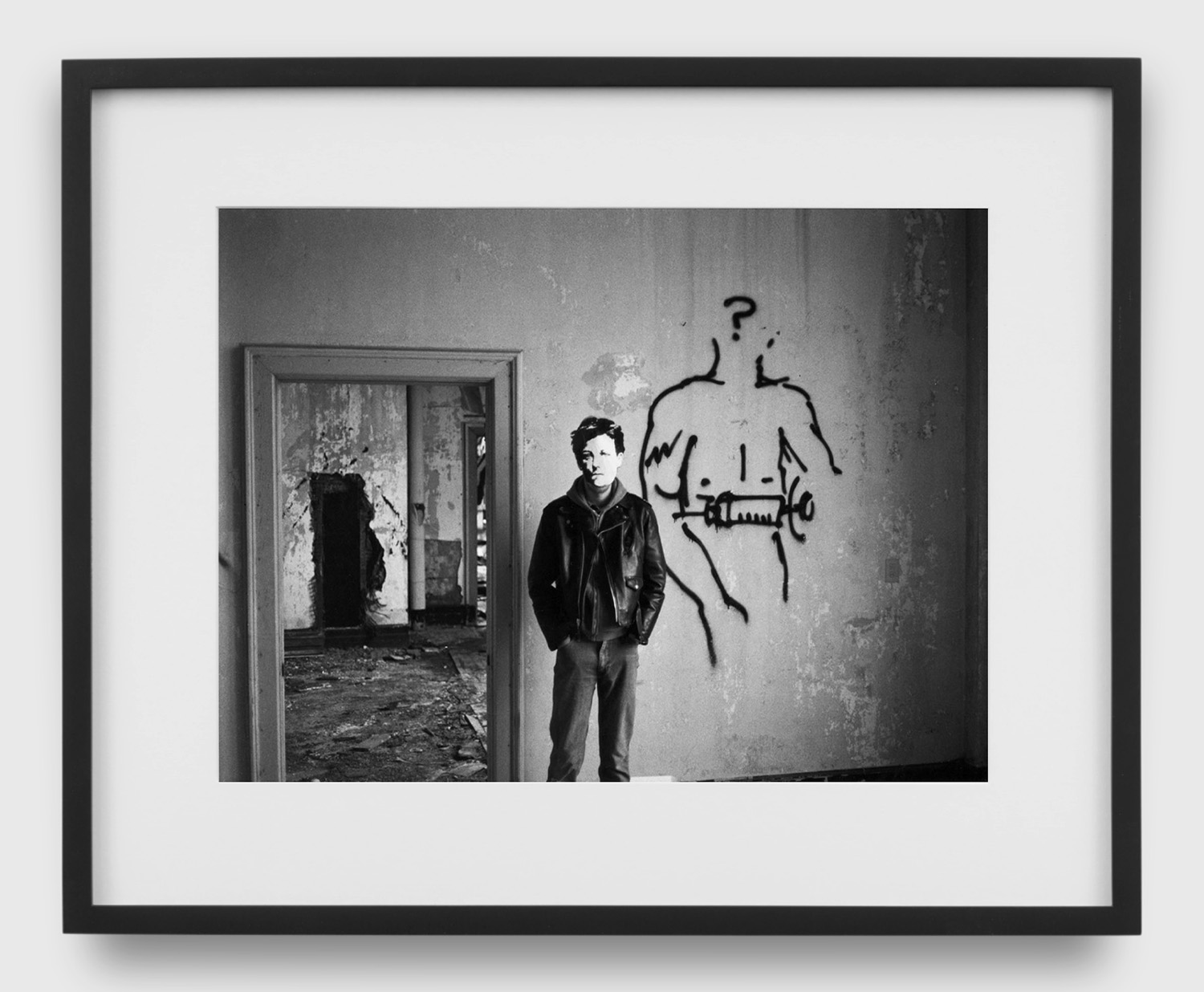

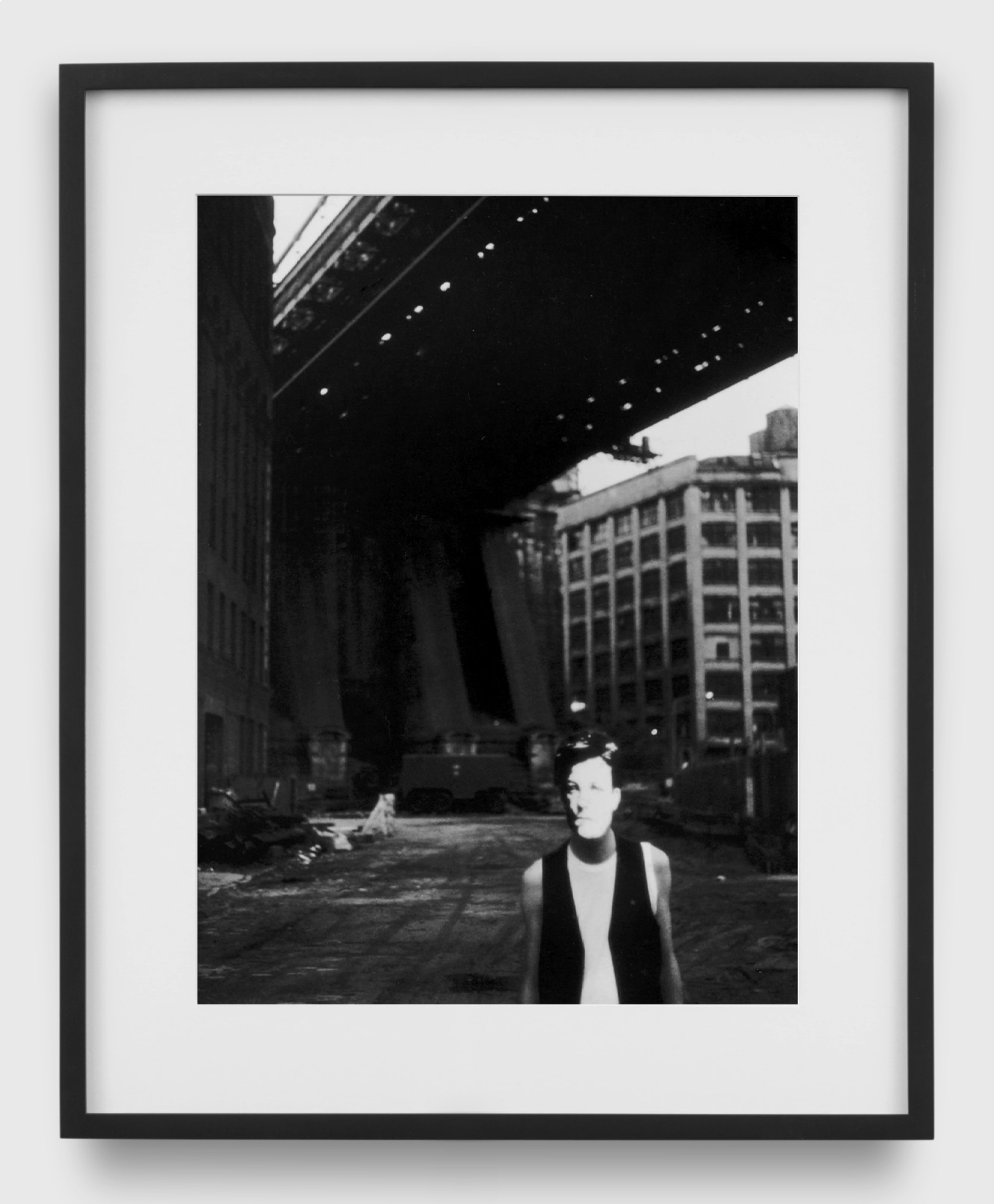

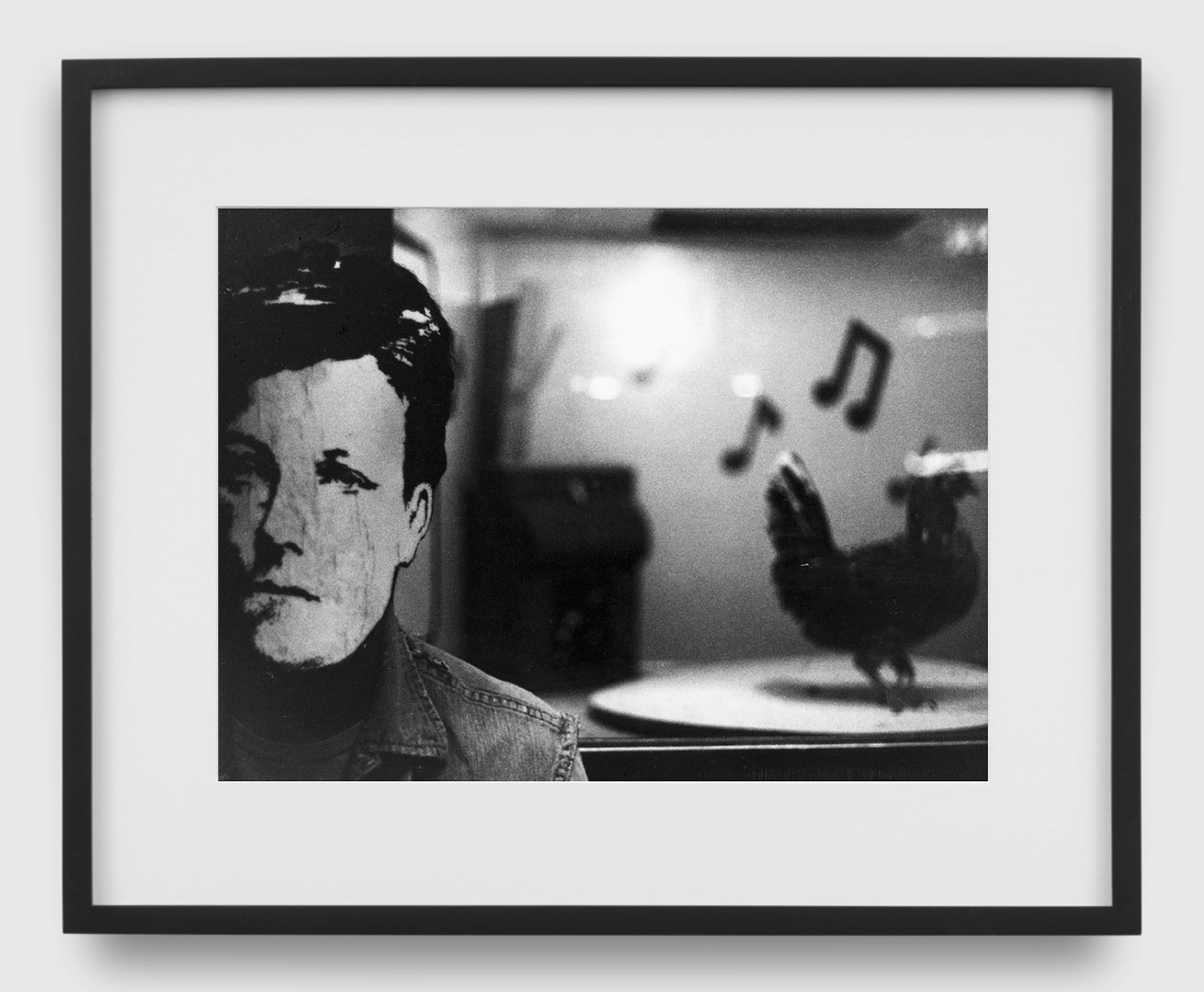

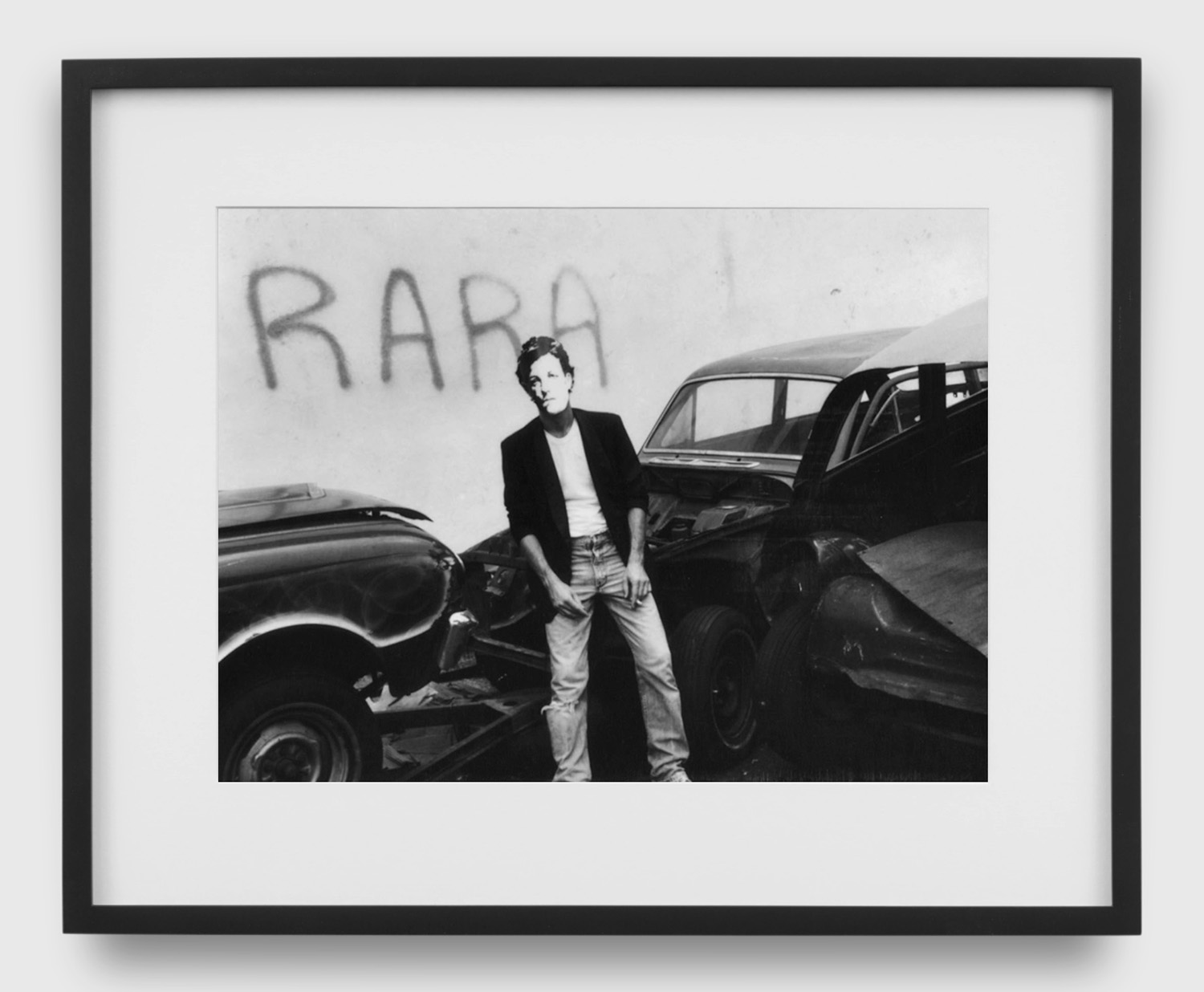

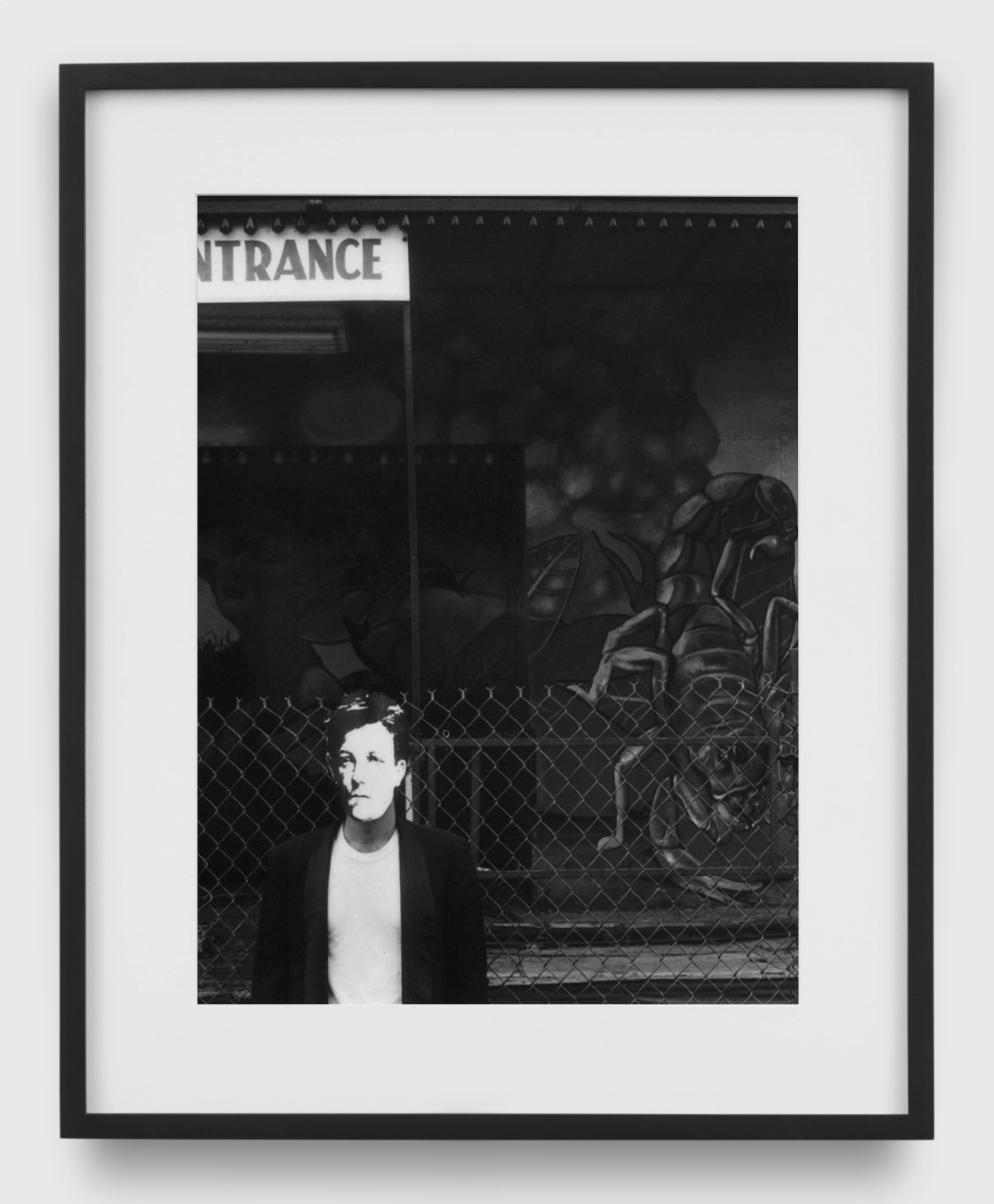

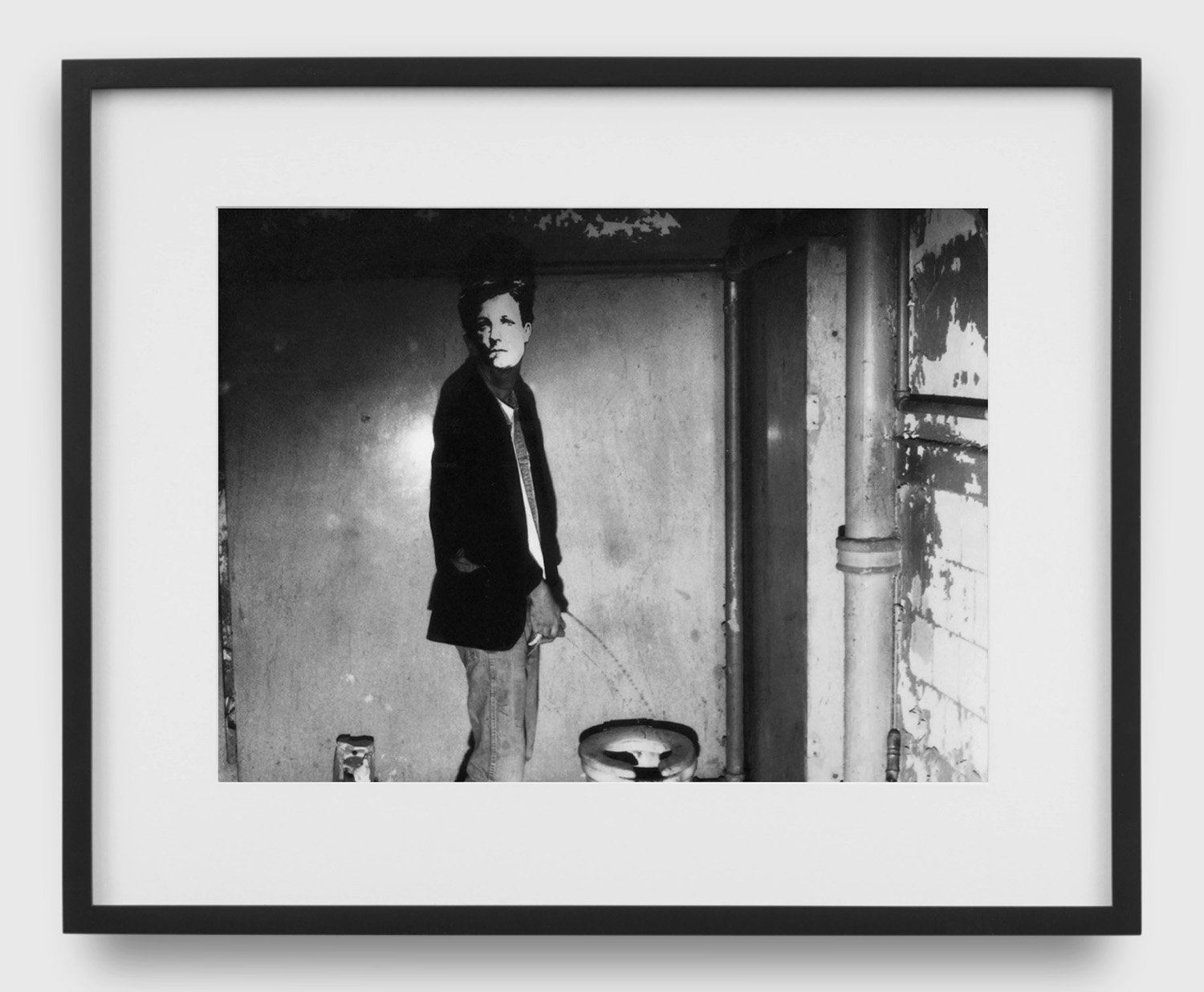

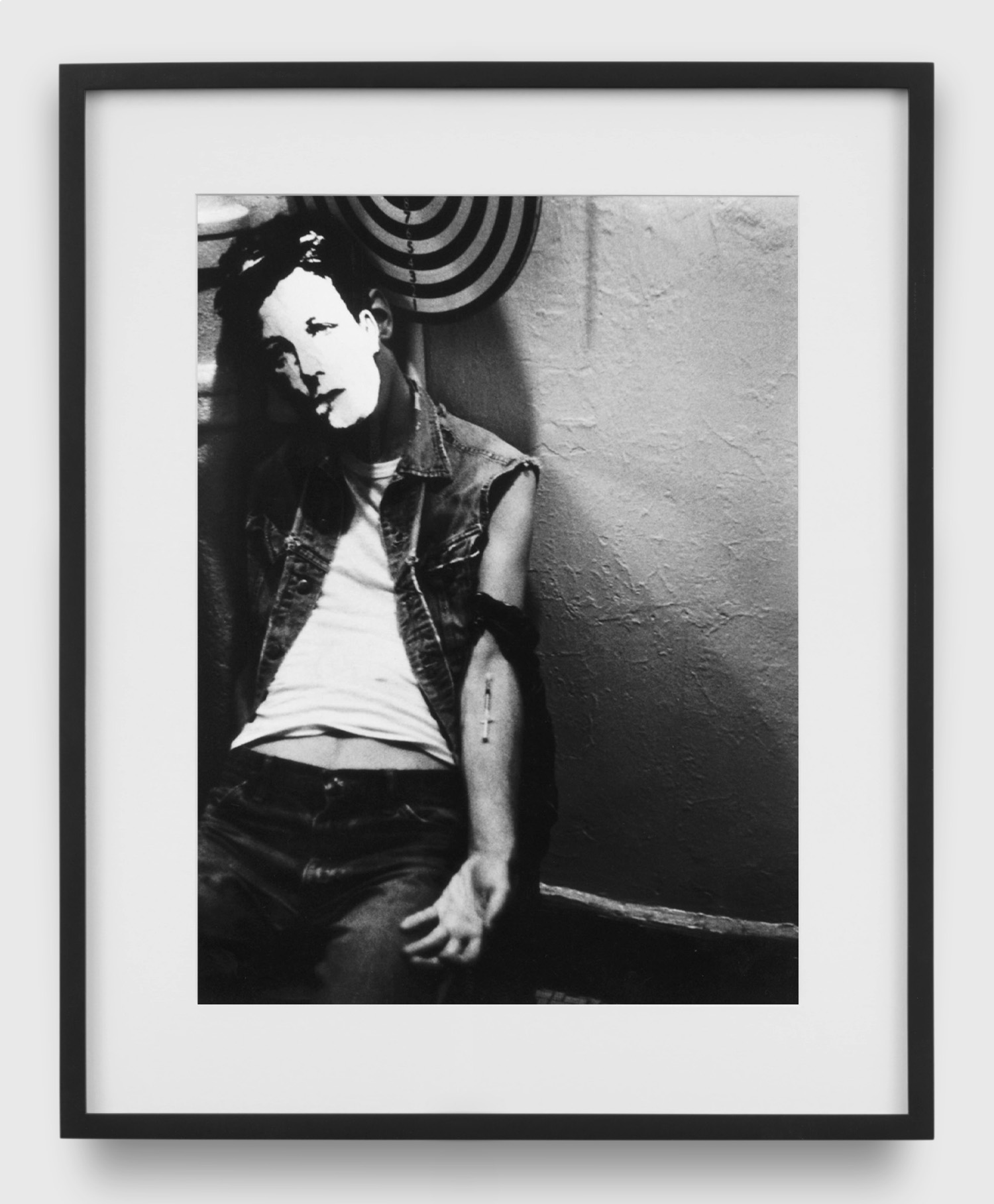

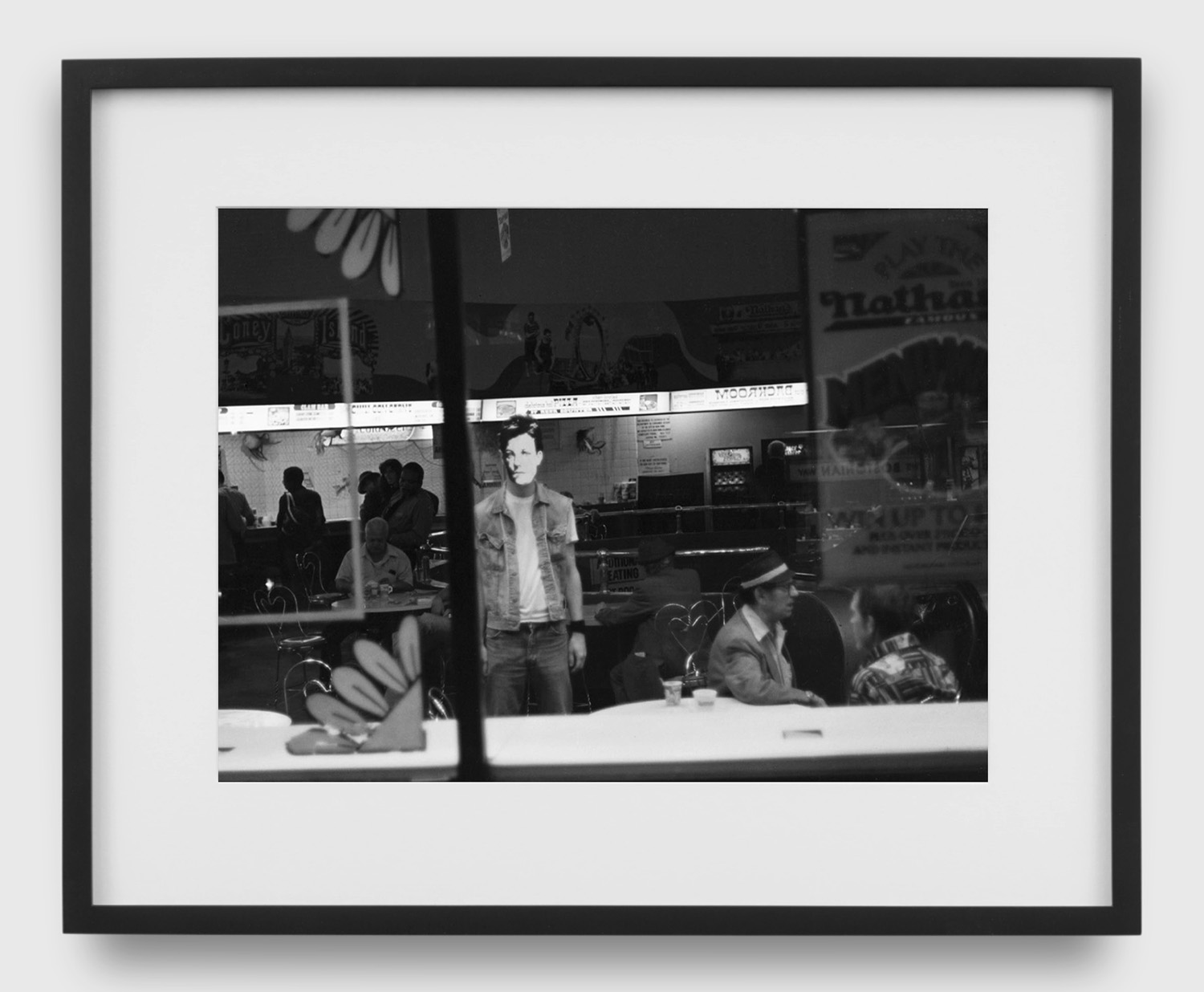

Morán Morán is pleased to present David Wojnarowicz: I is Someone Else, the gallery’s first exhibition of the artist’s work, which will include both photographs and film. Originally executed in 1978-79, the Rimbaud series is one of Wojnarowicz’s earliest bodies of work and this exhibition presents the series in its entirety. In addition to the 44 Rimbaud photographs, the film Beautiful People (1988) will be on view. The following is an essay by Evan Moffitt, commissioned for the occasion.

EYE HOLES

I see David Wojnarowicz in moments of crisis. His face is like an omen to me. Those dark, heavy-lidded eyes floated in and out of the moldering West Side piers in the decade before they came tumbling into the Hudson River. That thousand-yard stare, memorialized in gorgeous portraits by his friend and lover Peter Hujar, burned with righteous indignation. I saw him on November 9, 2016, in a crowd on 5th Avenue and 56th Street, as we gathered before Trump Tower. In that moment I thought I felt some of the rage he held inside for years “like a blood-filled egg.” My own blood trickled down my shoulder where his 1982 stencil of a burning house had been freshly etched into my skin. Lately, many people have found themselves in a country they can’t recognize, but decades ago, Wojnarowicz reminded us that America has always been this way.

“Photographs can save lives by creating informational vehicles from which all of us can draw in order to make informed decisions affecting the health and well-being of our bodies and our sense of identity in a country that trades heavily on the illusion of the One-Tribe Nation,” Wojnarowicz wrote in 1990. He recognized the biopolitical power of the camera in an age of disinformation. I wonder what he would make of a president who spouts bunk science on TV in the middle of a viral pandemic. He might be more surprised by the way the world now talks of “vectors,” a concept best articulated by the HIV/AIDS activists he knew in ACT UP, with their ethics of mutual care. What would he think of our masks?

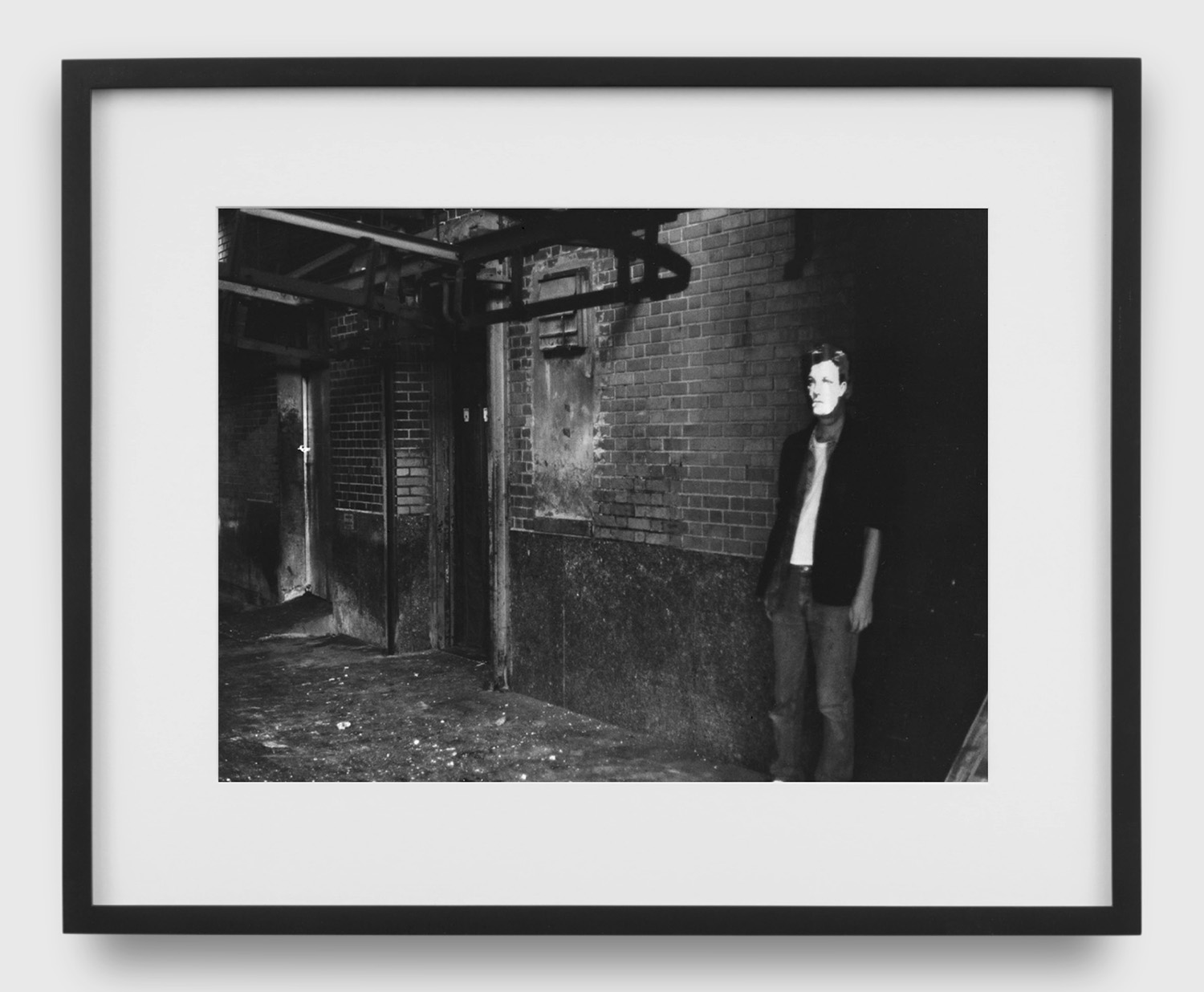

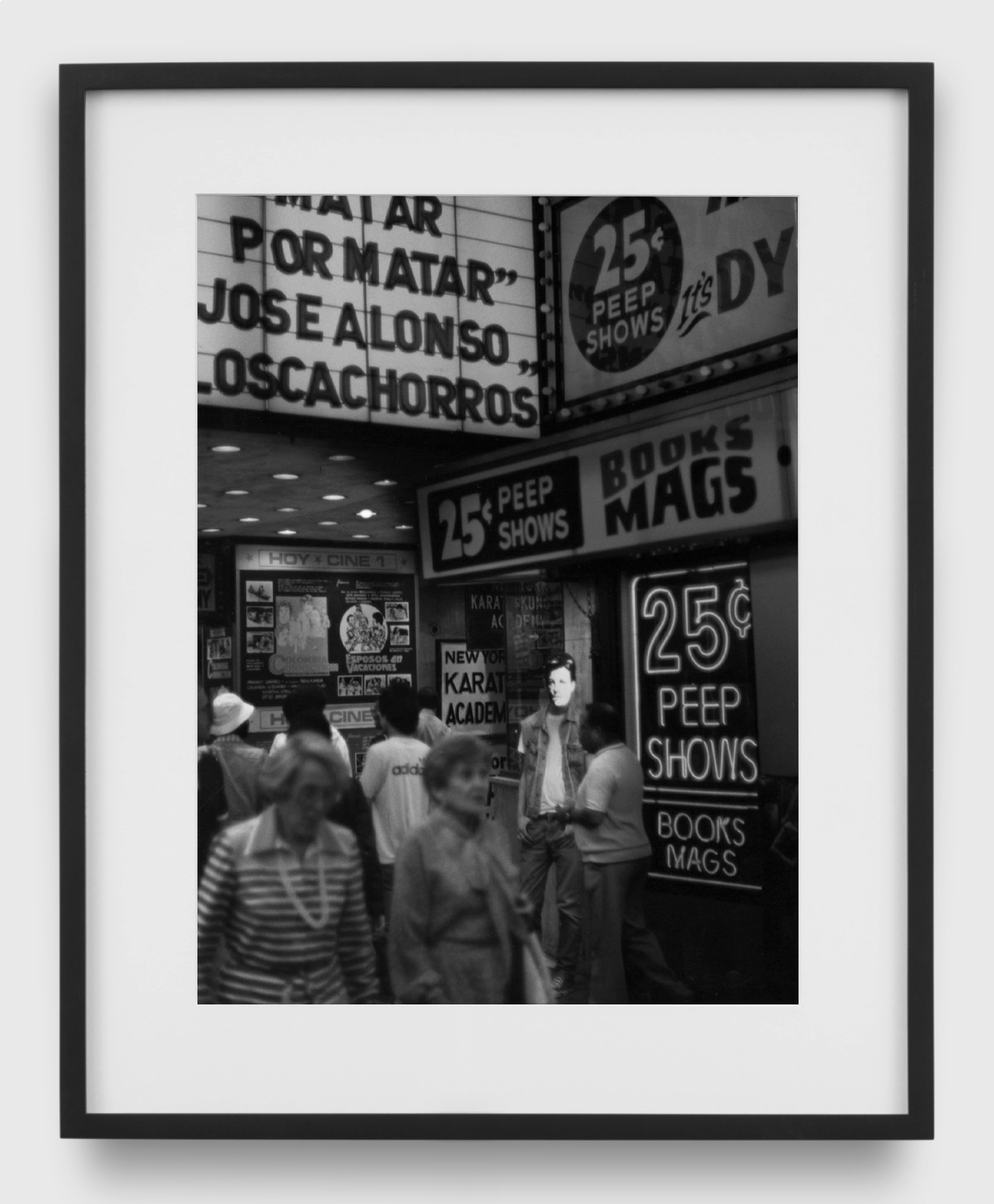

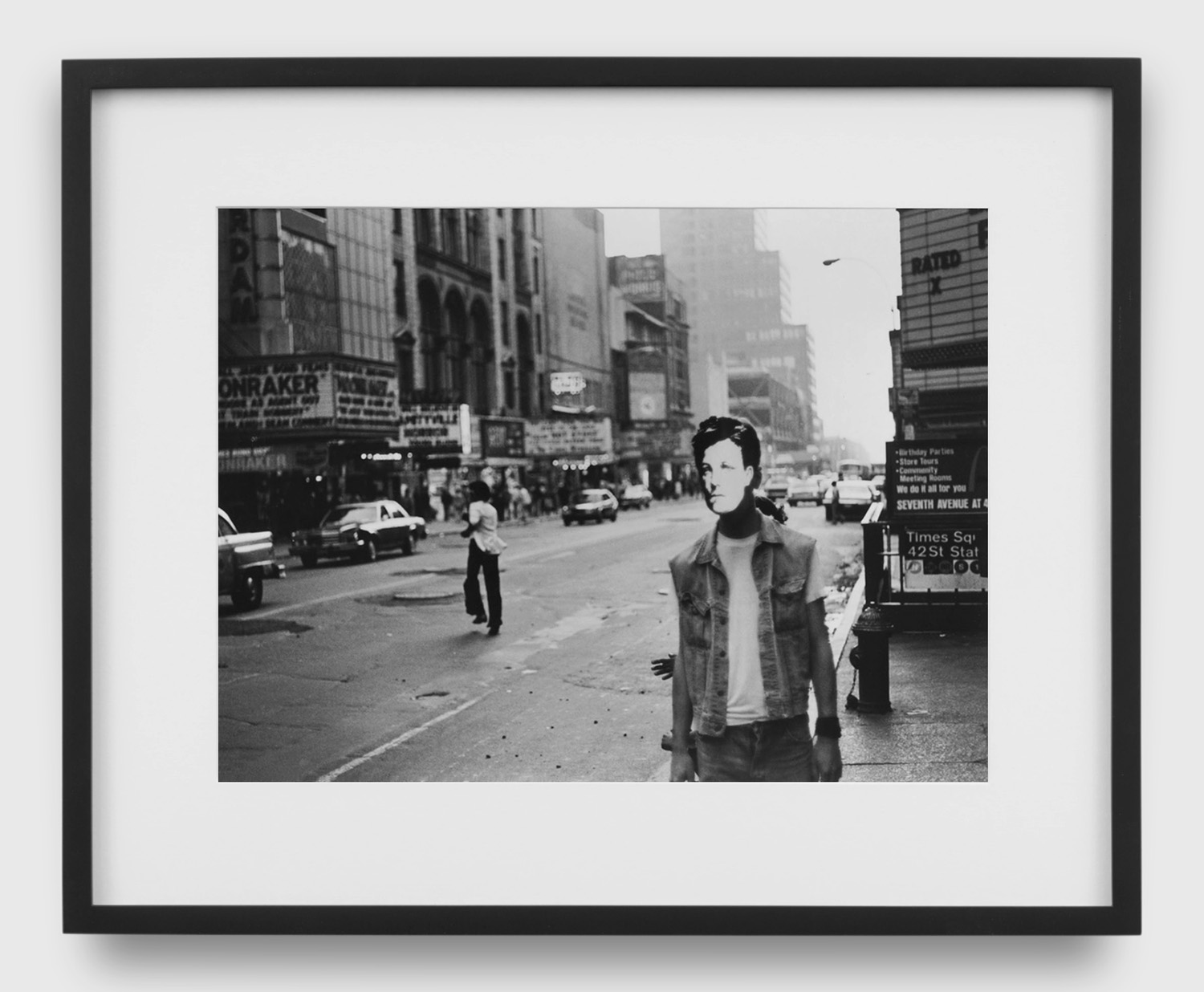

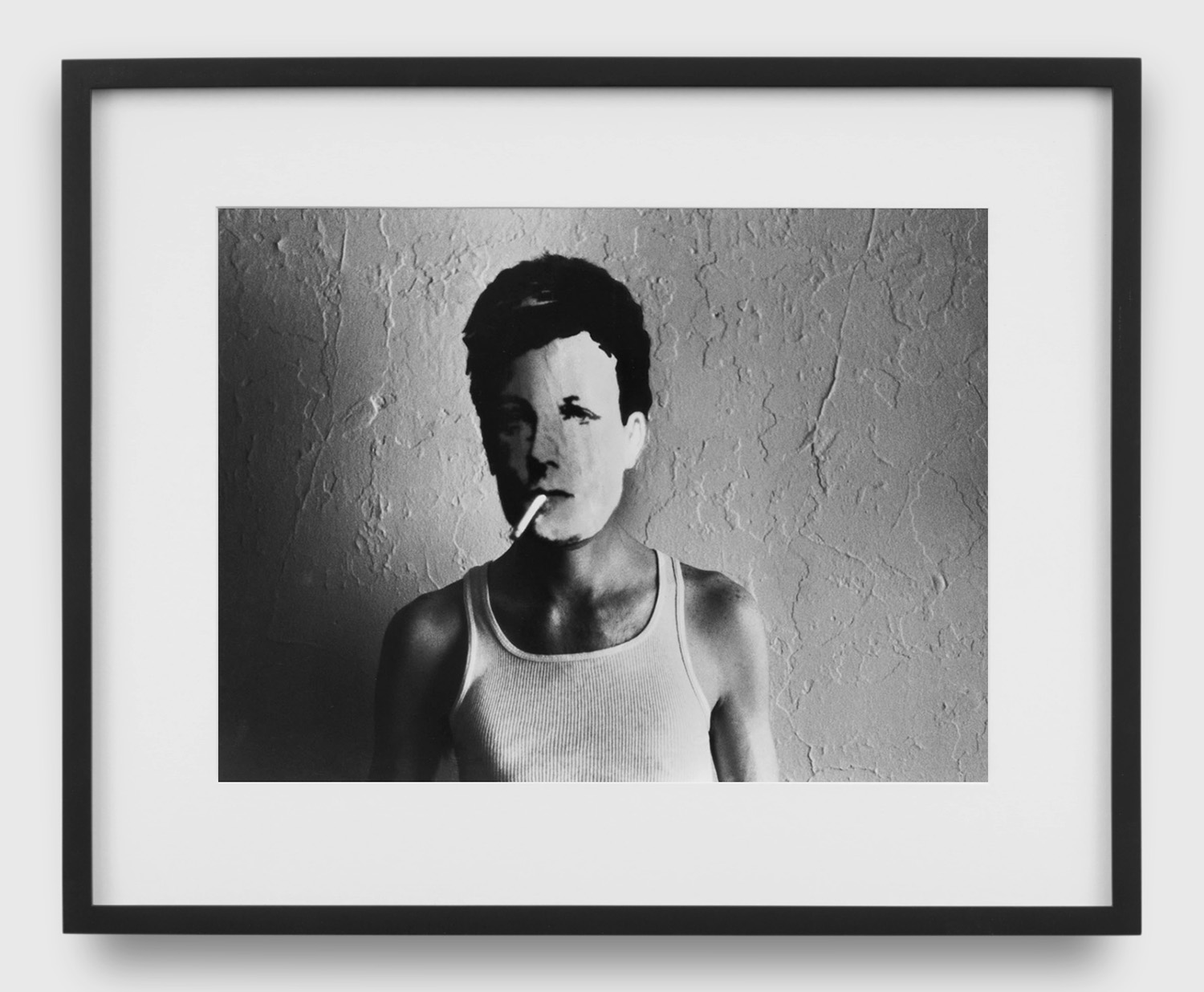

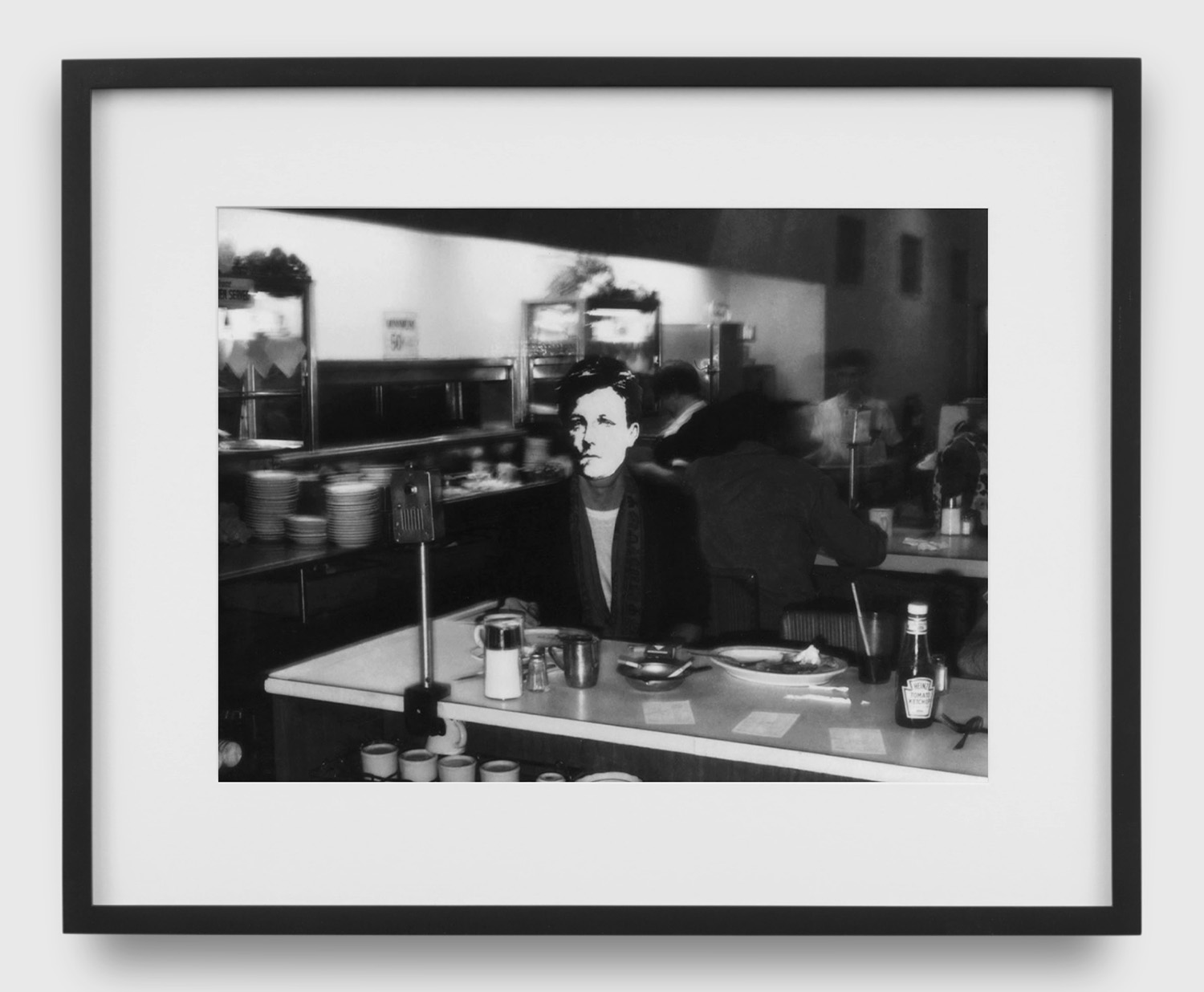

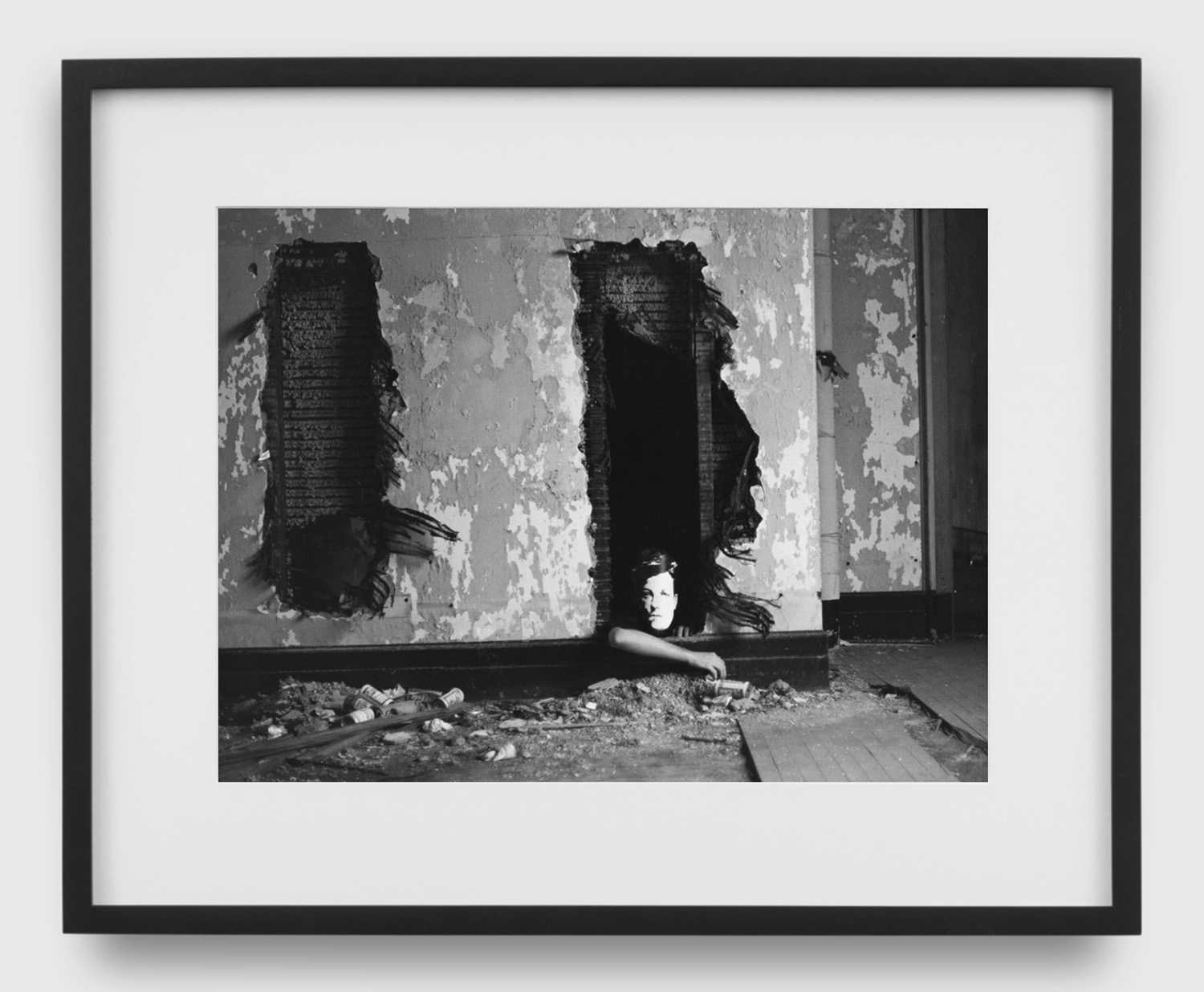

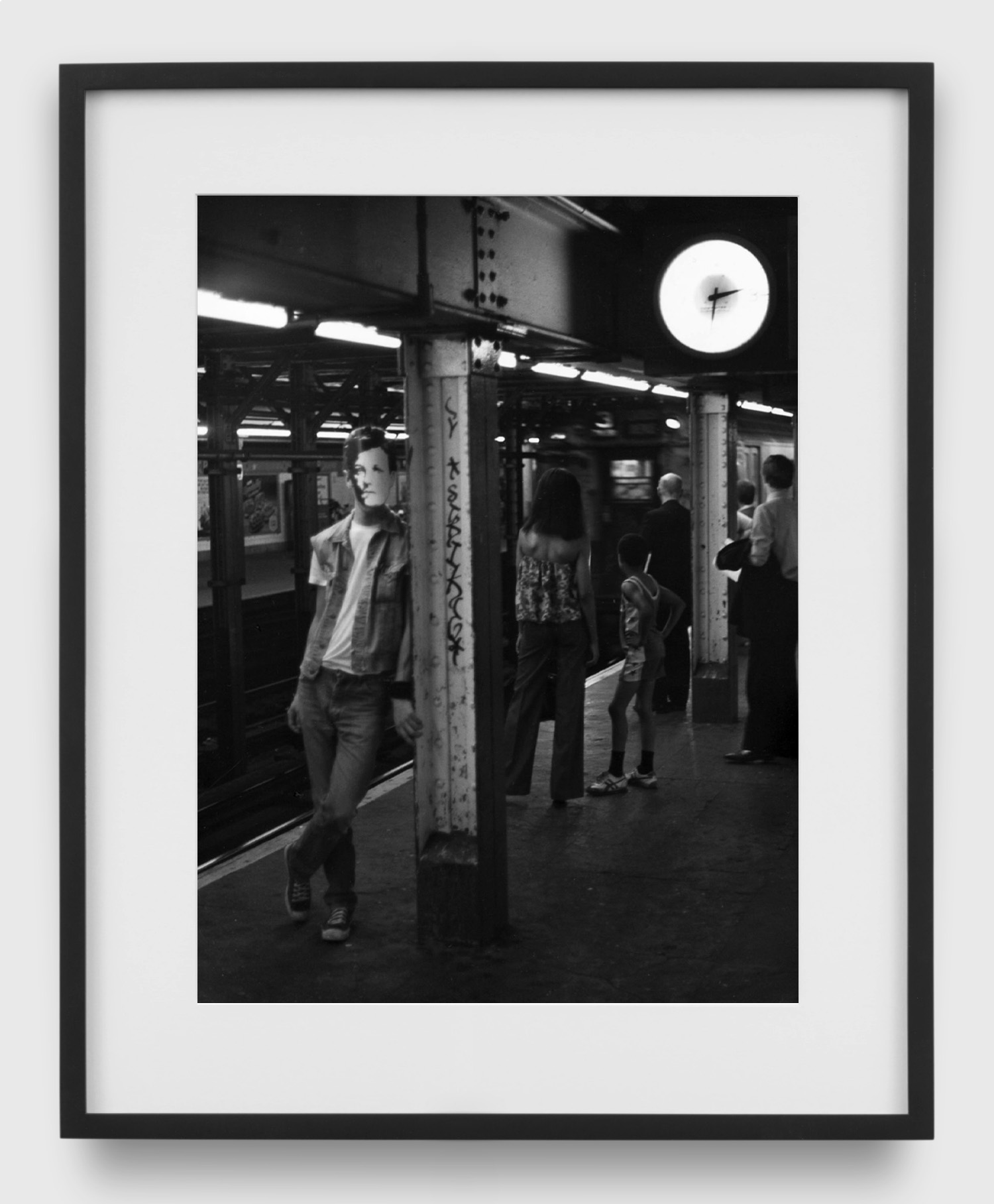

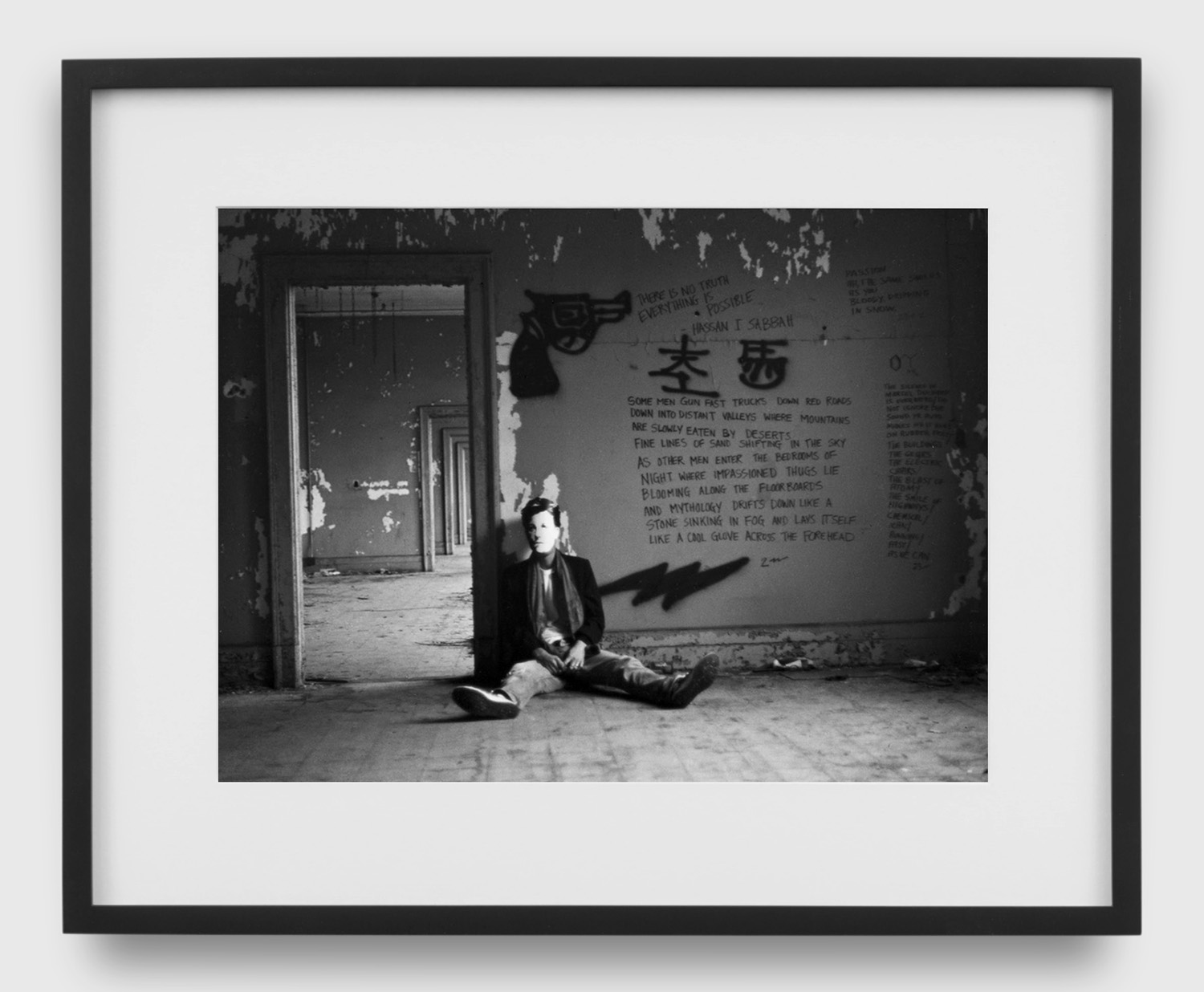

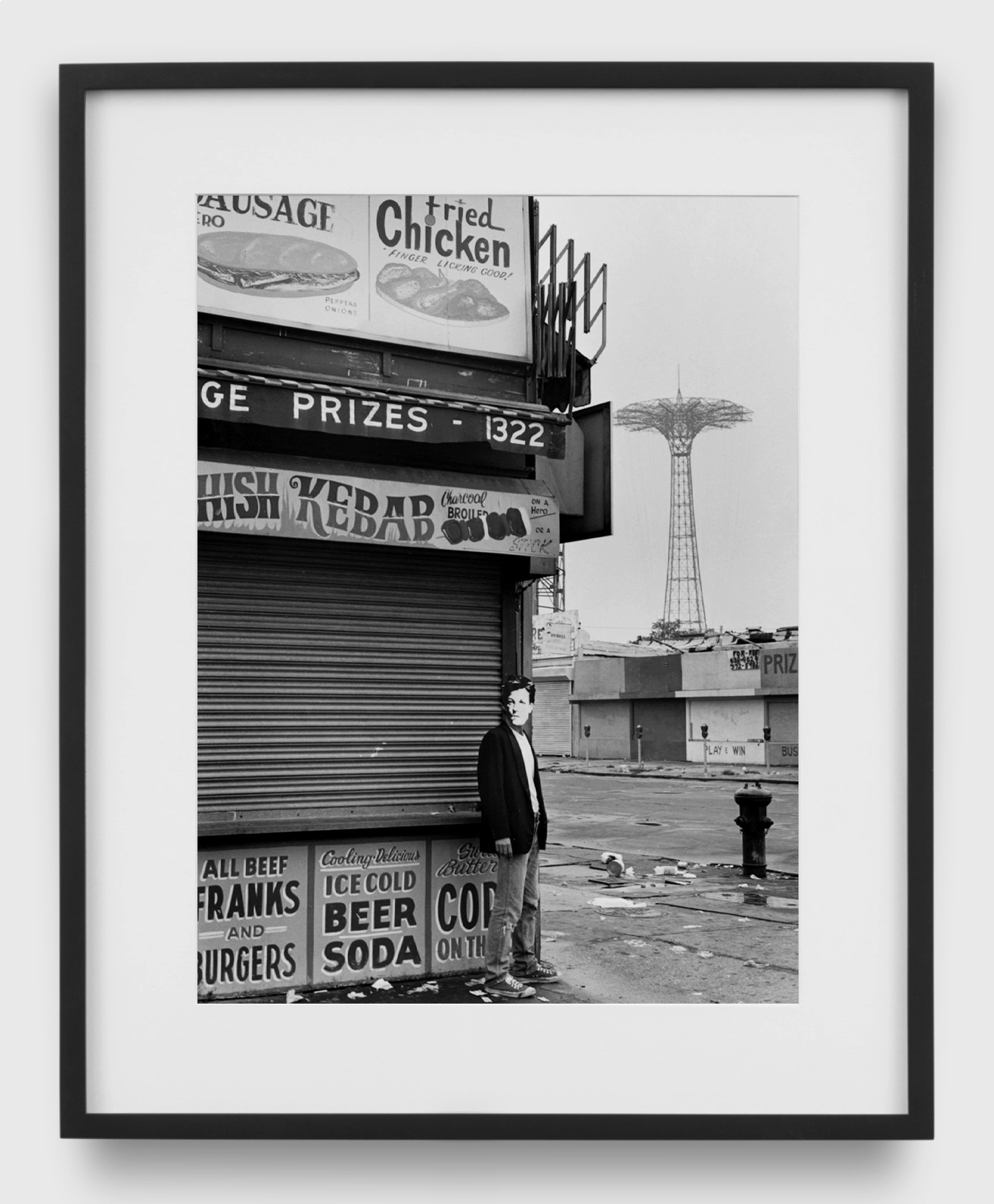

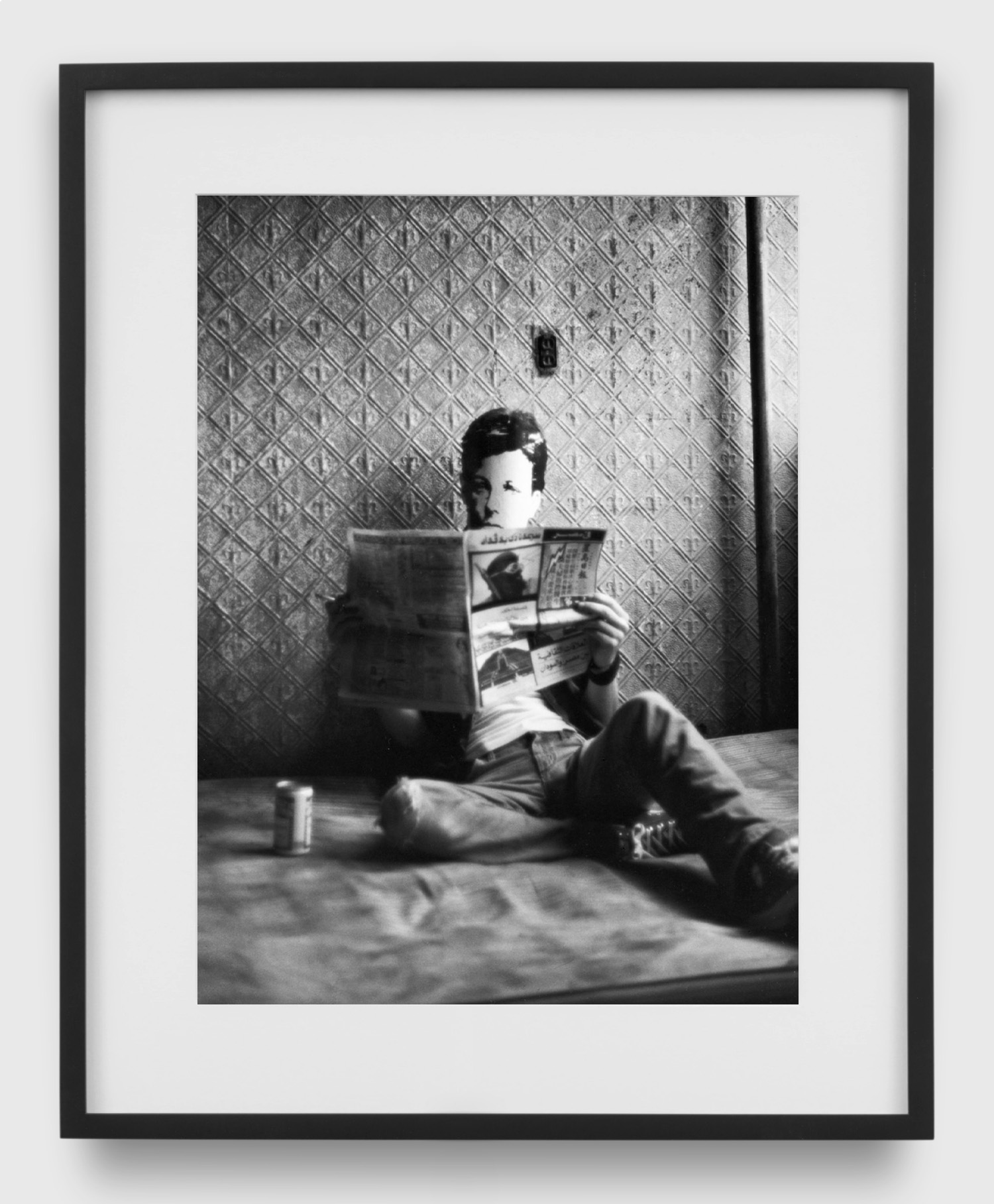

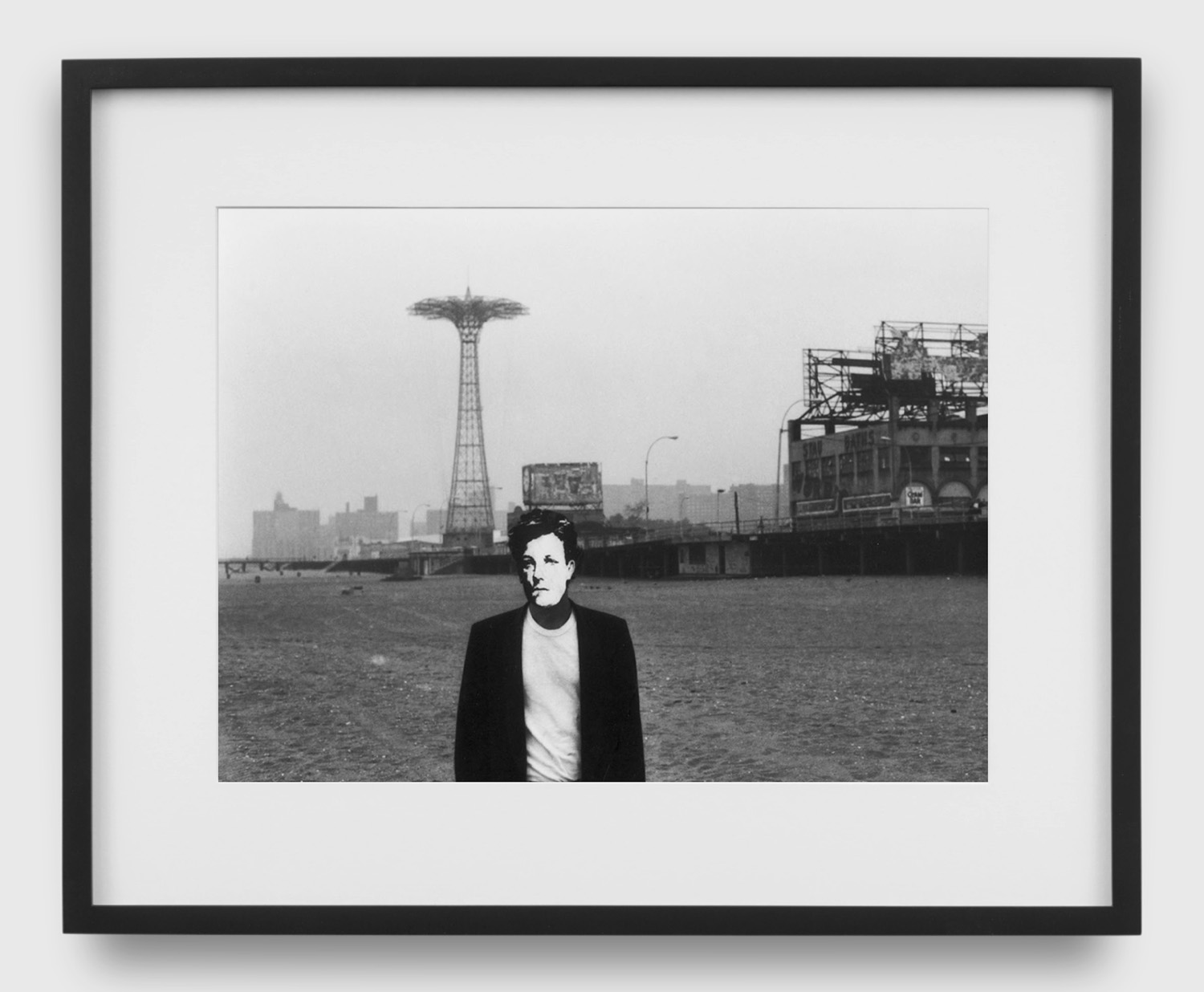

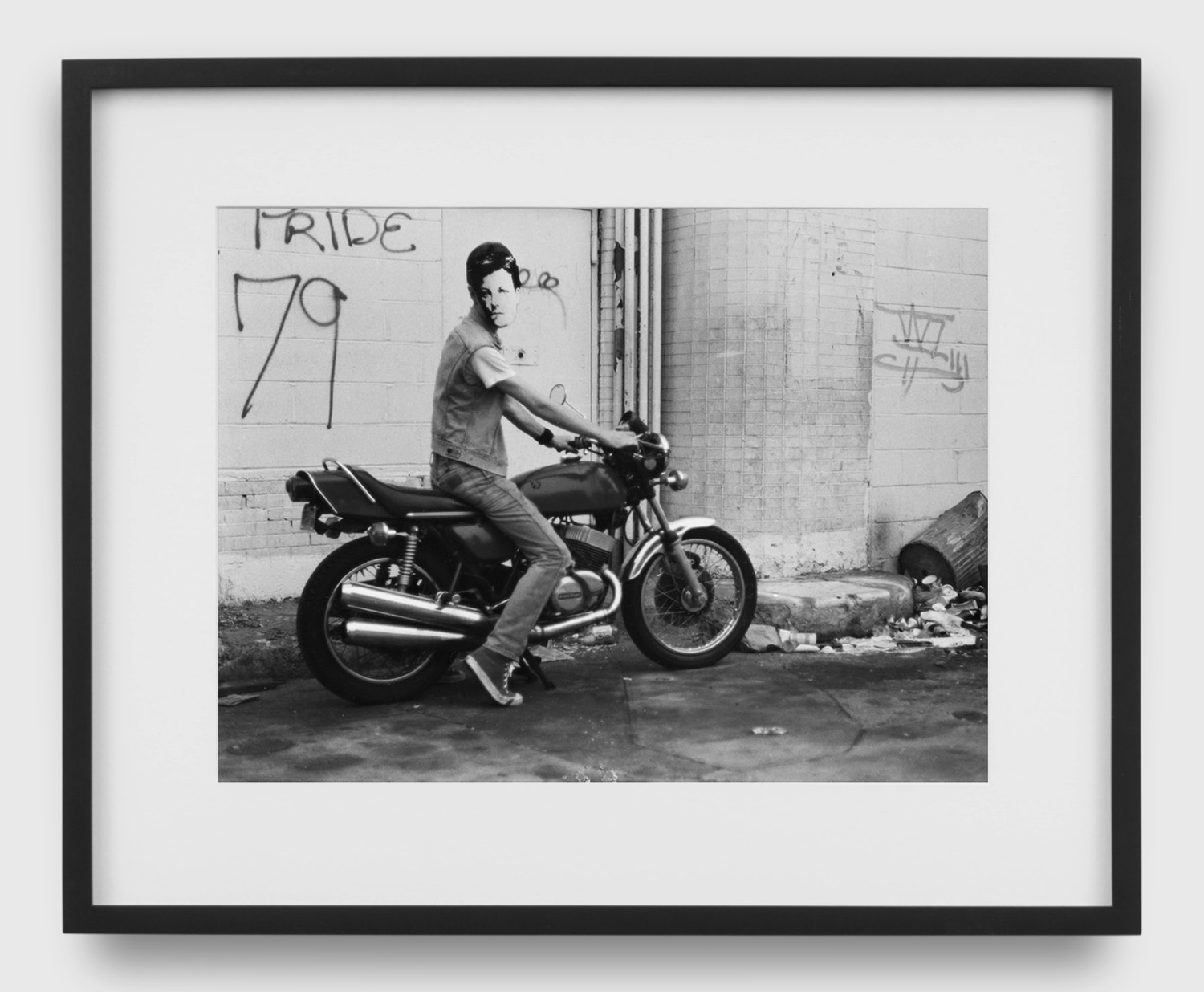

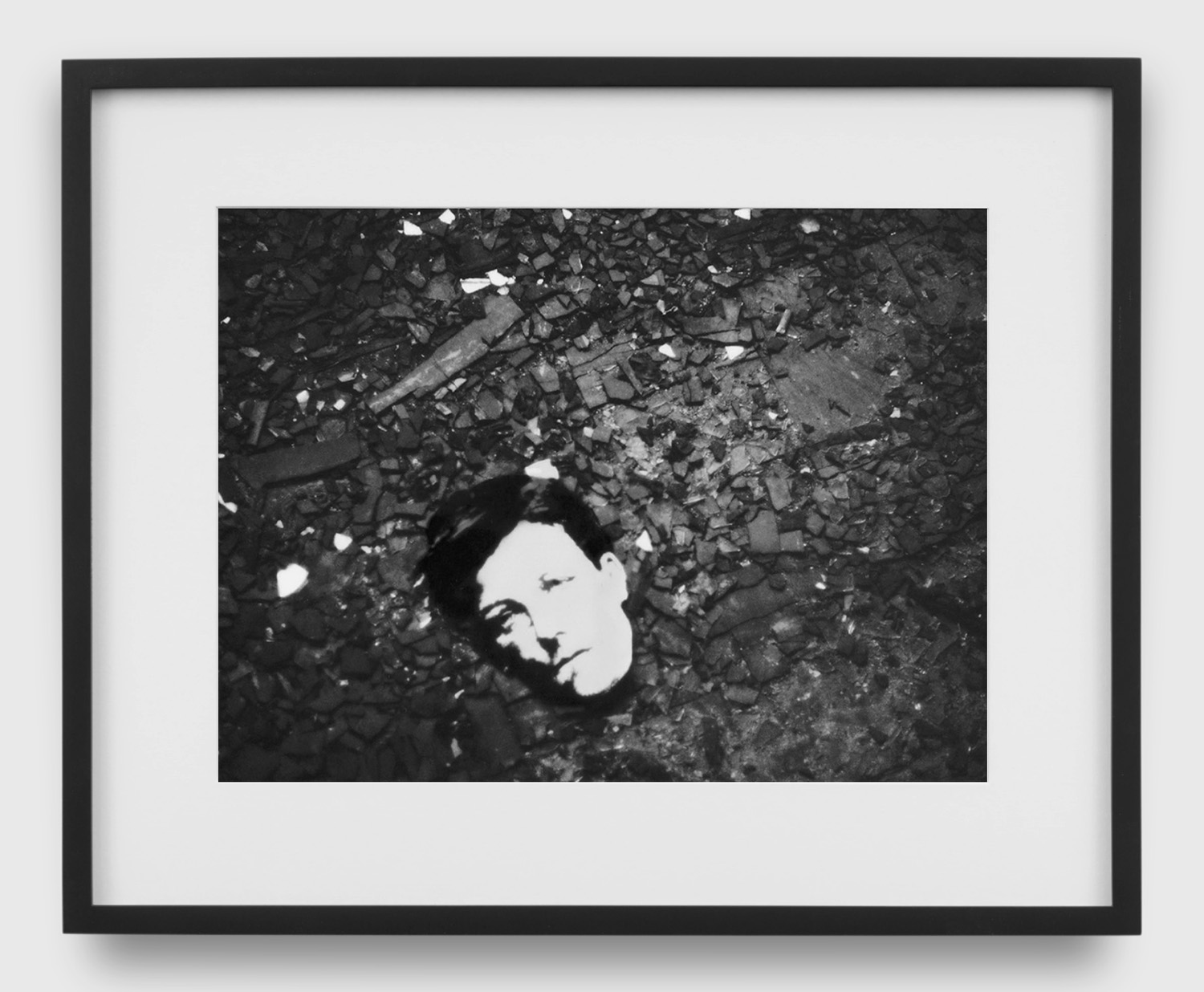

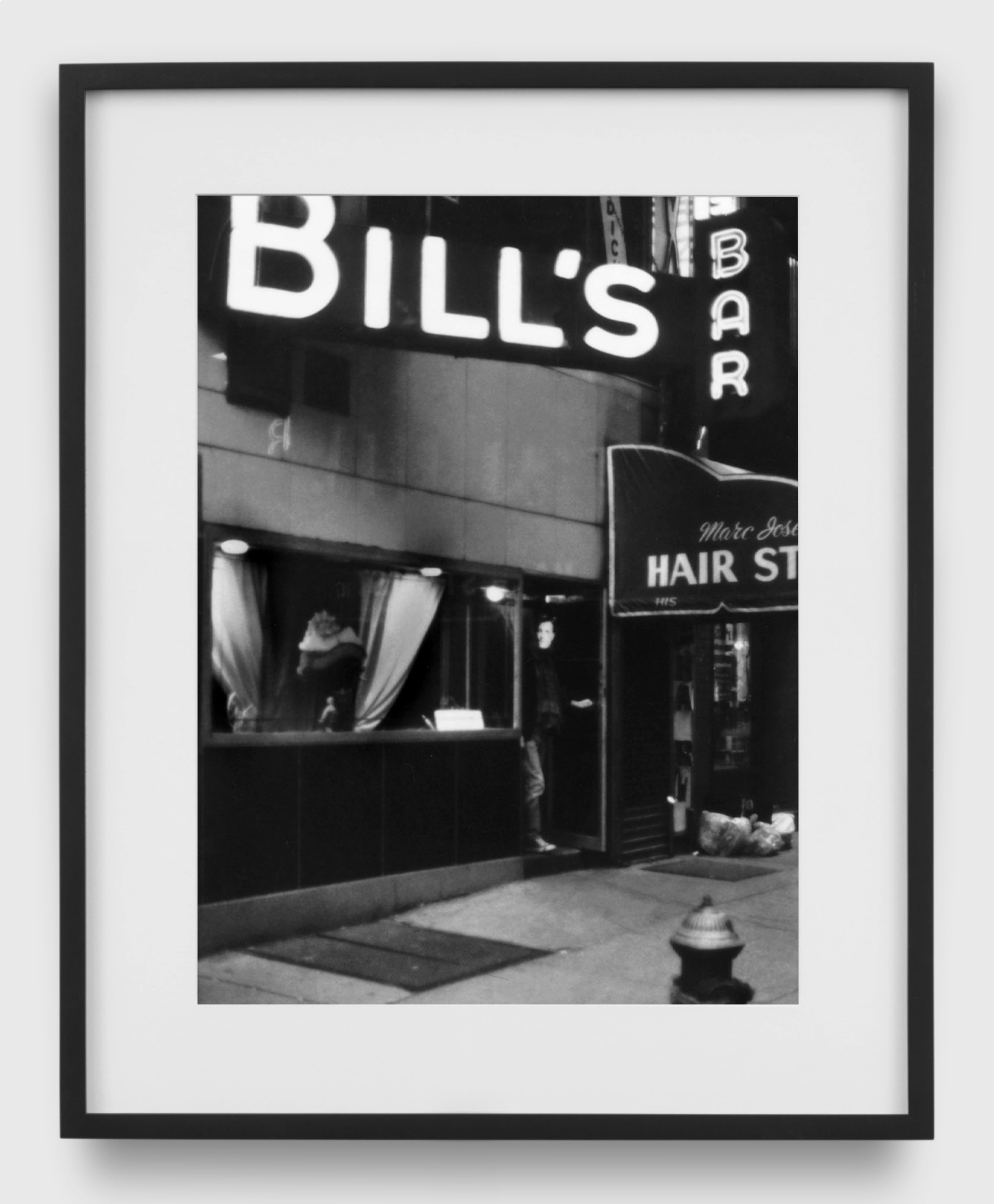

I’m wearing a mask when I cycle to Coney Island in late March in preparation for this essay. Writing feels impossible with so much death in the air. I pass refrigerated trucks awaiting corpses on my way down Flatbush Avenue. The day is bright and gelid. It was cold, too, when Wojnarowicz came to Coney with his boyfriend, Jean-Pierre Delage, in January 1979, to take photographs for a series he had been working on. I don’t know what I’m looking for on the empty beach beneath the Parachute Jump, a palm tree of cherry-red steel, but I think of Wojnarowicz’s photograph of Delage standing on the trash-strewn boardwalk, a cardboard mask of Arthur Rimbaud strapped to his face, the Jump still and silent behind him. Rimbaud, the notorious hedonist, wandering through the ruins of a pleasure park. Throughout Rimbaud in New York, which Wojnarowicz completed in 1979, the homosexual French poet haunts the streets of a New York that is falling apart, finding lonely pleasures in the rubble. Here is Arthur shooting heroin; Arthur waiting for the 3 train; Arthur cruising the unpaved underpass of the Manhattan Bridge. The photostat mask, which Wojnarowicz enlarged from the cover of his paperback copy of Rimbaud’s Illuminations (1886), is worn by the artist but mostly by his lovers and friends, as specific a reference as it is profoundly anonymizing.

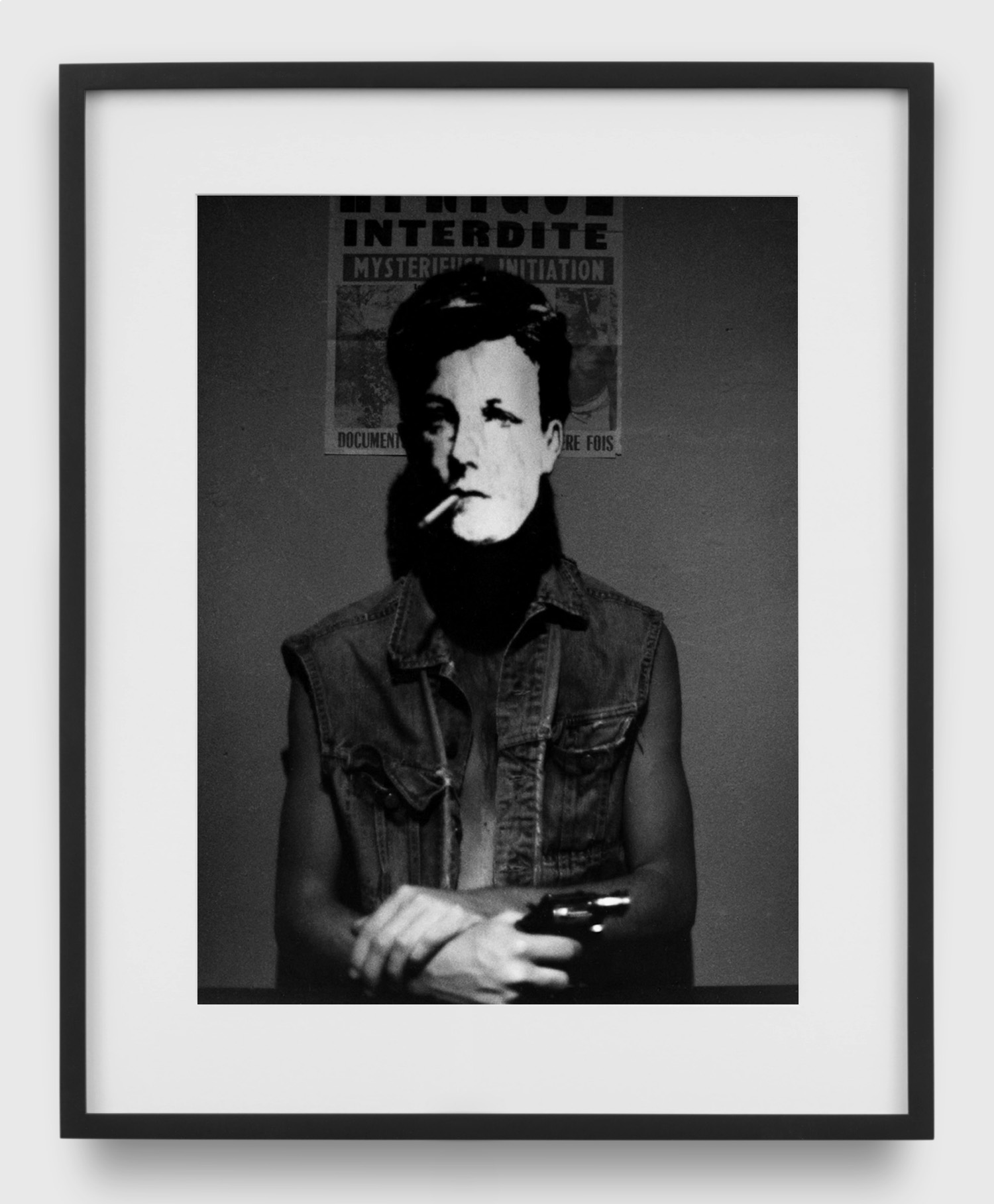

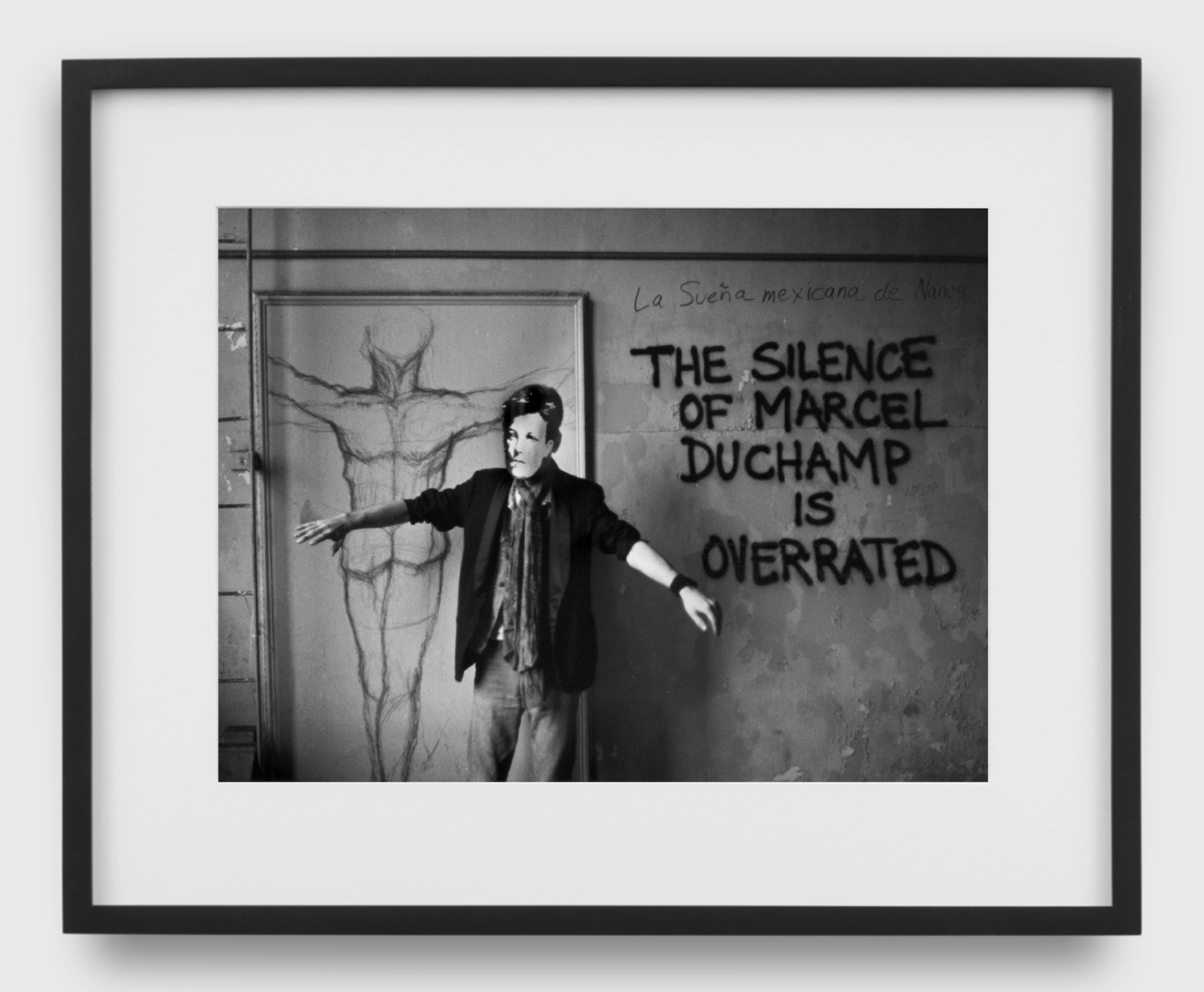

In Season in Hell (1873), the poet vows to destroy all that binds him to European civilization, words that then must have rung with shocking iconoclasm. Rimbaud wished to lose himself in “sin” until his own subjectivity disappeared: “I ought to have a hell for my anger, a hell for my pride, – and a hell for my caresses; a concert of hells.” Music to Wonjarowicz’s ears. Like Rimbaud, the artist had always considered himself an outcast, even before he fled his abusive father at age 14 to hustle in and around 42nd Street. (Here is Arthur, another refugee of a broken home, emerging from a Times Square peep show.) But the image of Rimbaud, the mask, first came to Wojnarowicz while he was cruising along the Seine in late 1978. There, he spotted a poster bearing the same photograph of the Symbolist and peeled it from the ancient embankment walls. It was around then, too, that he met Delage at a popular cruising spot in the Tuileries, writing later in his diary that he had hooked up with “a stranger leanin against the midnight doors of the Louvre.” He began working on what he called “the Bolt book,” after a lightning bolt he used to symbolize Rimbaud’s “vision behind the eyes.” Rimbaud in New York, which Wojnarowicz shot upon returning to New York, contains many French cues that are often overlooked: here, Arthur poses with a gun in front of a poster for a certain ‘Mysterieuse Initiation;’ there, his face floats beside a singing Gallic cock. More than anything, though, New York is the subject, a city of “hard street energies, manic violence… and tension,” as he wrote in his diary days after arriving from Paris. Like his outlaw idols, Rimbaud and Jean Genet, Wojnarowicz felt most at home in places the state wrote off as criminal or perverted. To be a man fucked by men then was to say Fuck You to the Man.

Rimbaud’s teenage jaunts through Paris coincided with Baron Hausmann’s wholesale destruction of the medieval city, a warren of narrow streets where sewage often flowed between brothels and bistros and where the young poet loved to sip absinthe. “I would drag myself through stinking alleys, and, eyes closed, offer myself to the sun, god of fire,” he wrote in Season in Hell. Some blocks took decades to fill, leaving behind gaping wounds in an already blighted urban landscape. In 1979, New York’s own massive redevelopment plan had stalled due to huge budgetary shortfalls, and millions of tons of landfill along Manhattan’s southern tip lay barren and strewn with garbage. Battery Park was, for nearly ten years, the image of a city in the midst of erasing itself, and a metaphorical backdrop against which Rimbaud in New York was taken.

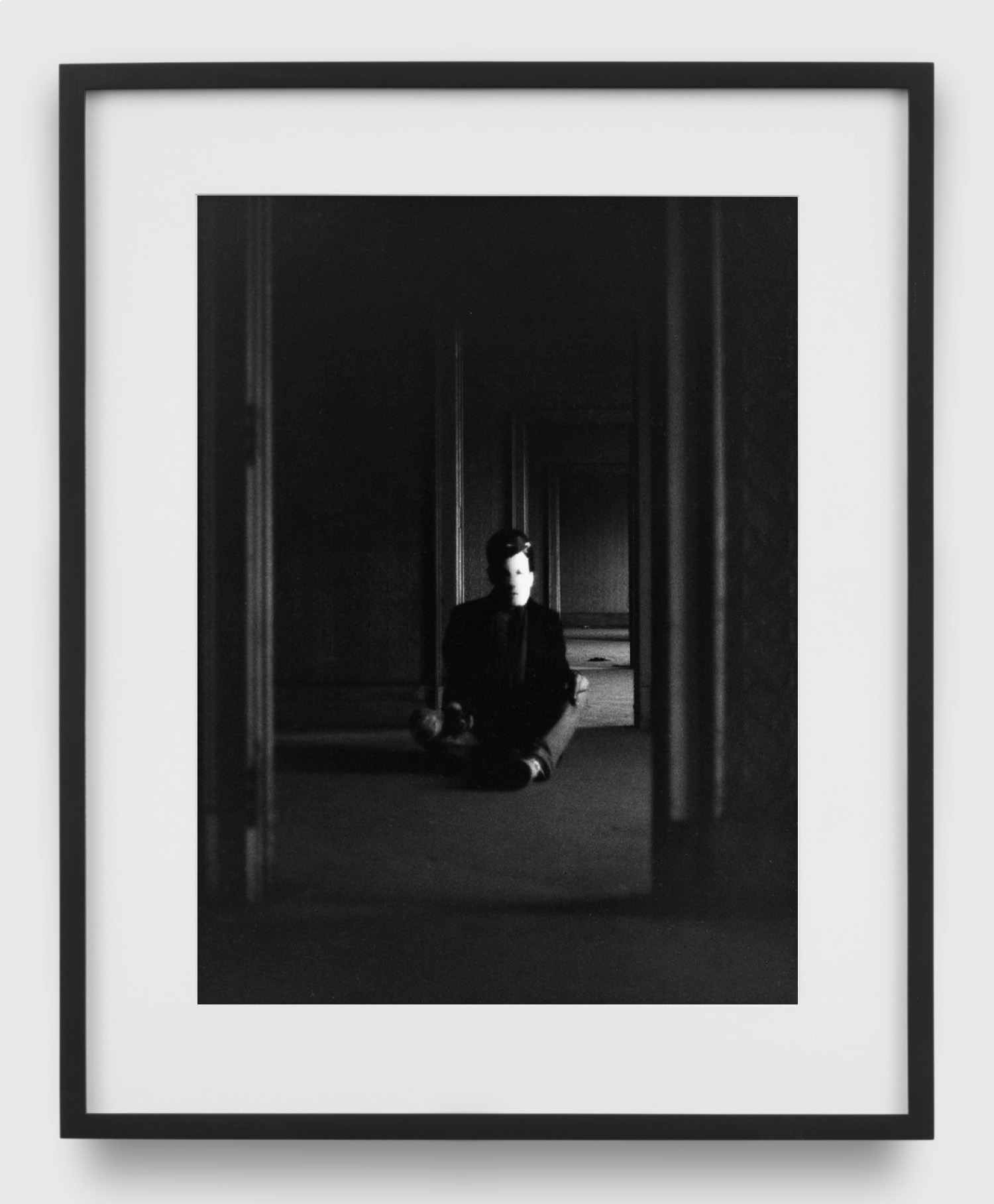

Wojnarowicz’s early journals and the accounts of cruising he published in his first book Close to the Knives (1991) connect the desiring body with the architecture of New York in much the same way that the Symbolists had hoped to collapse together orders of sensory experience. He loved the way light poured through holes in the wooden piers, illuminating the cocks, hands, faces of men passing through their shadowy interiors. Entropy appeared to have designed these spaces for voyeurism. So many of Wojnarowicz’s photographs and films are bathed in this light, in some sense reproducing the technology of the camera. Perhaps the holes in the landscape left by the ravages of late capitalism and “urban redevelopment” were a kind of aperture, too, through which he could see the future of the city more clearly. Now those holes are plugged so fully it can be hard to tell that they were ever there.

If a photograph flattens a man, a Xerox obscures him even further. The mask makes Rimbaud what Craig Owens called a “specular image,” a symbol rather than a direct representation. It speaks to everyone who has ever felt lonely at the margins. As Rimbaud formulated, “Je est une autre” – “I is Someone Else.” In these photographs, this I, or eye, is a kind of hole through which we can see layers of social difference often hidden from view. “A photographic image can be a disruption of previously unchallenged power,” Wojnarowicz observed. Like so much of his work, these pictures shoot the myth of our One Tribe Nation full of holes, so we might finally be able to see some light.

Evan Moffitt

New York City, 2020

To ensure the health and security of our community, we will be implementing enhanced safety measures in accordance with government regulations. With these concerns in mind, kindly note that we will be taking the following precautions:

– All staff and visitors are required to wear masks.

– The gallery will admit a maximum of six visitors at a time and have reduced staff on-site.

– All staff and visitors must maintain a social distance of no less than 6 feet.

– Appointments are encouraged.

Thank you to everyone at P•P•O•W, New York and the Estate of David Wojnarowicz for their generous support of this exhibition.

Dates

September 26 - November 07, 2020Opening Reception

Saturday, September 26, 11am - 6pmLocation

937 N. La Cienega Blvd.Los Angeles, CA 90069

Artist

David Wojnarowicz

Installation Views

All images: I is Someone Else, 2020. Photography courtesy of Morán Morán

Installation view

I is Someone Else, 2020

Photograph courtesy of Morán Morán

Installation view

I is Someone Else, 2020

Photograph courtesy of Morán Morán

Installation view

I is Someone Else, 2020

Photograph courtesy of Morán Morán

Installation view

I is Someone Else, 2020

Photograph courtesy of Morán Morán

Installation view

I is Someone Else, 2020

Photograph courtesy of Morán Morán

Installation view

I is Someone Else, 2020

Photograph courtesy of Morán Morán

Installation view

I is Someone Else, 2020

Photograph courtesy of Morán Morán

Installation view

I is Someone Else, 2020

Photograph courtesy of Morán Morán

Installation view

I is Someone Else, 2020

Photograph courtesy of Morán Morán

Installation view

I is Someone Else, 2020

Photograph courtesy of Morán Morán

Installation view

I is Someone Else, 2020

Photograph courtesy of Morán Morán

Artworks

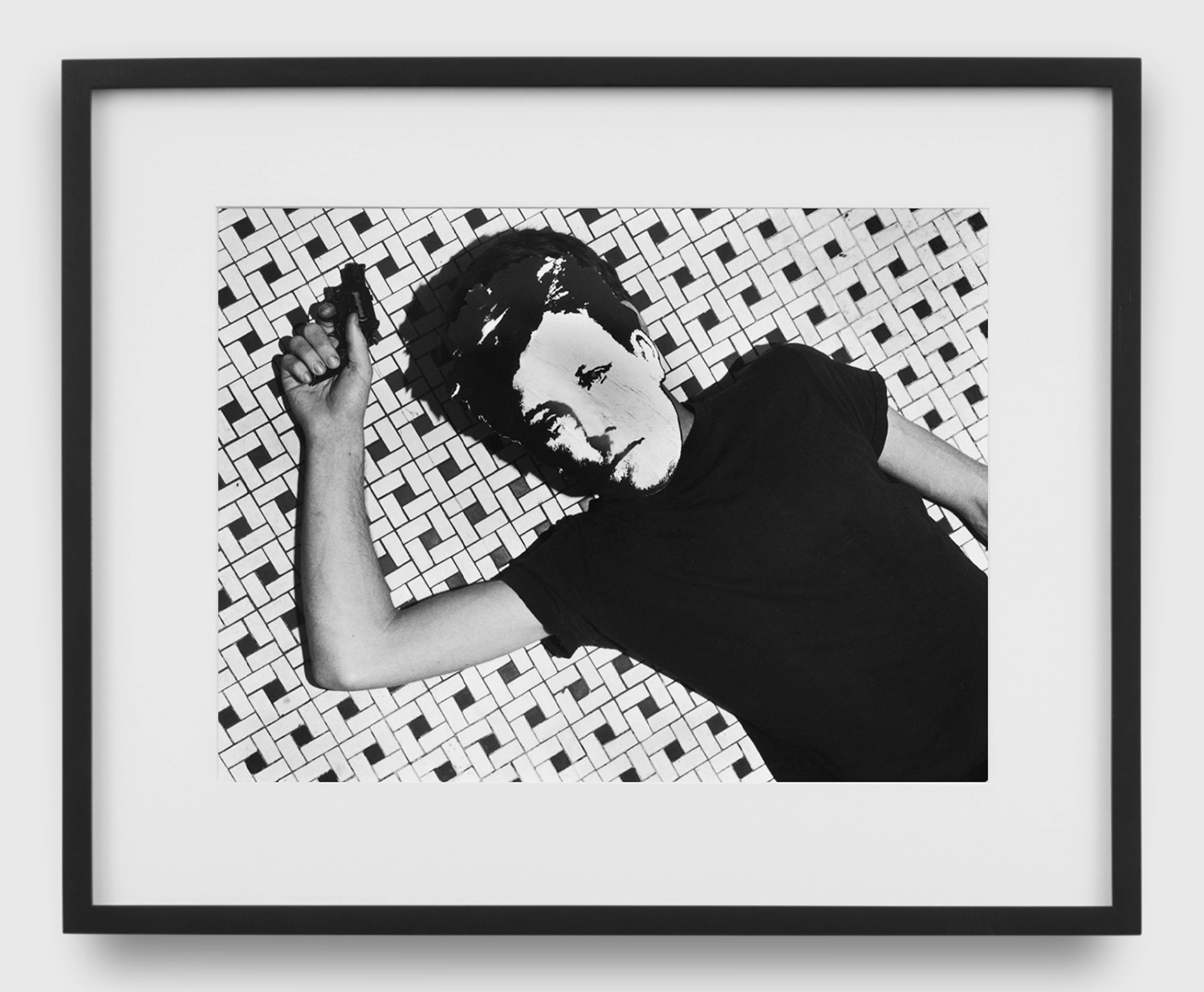

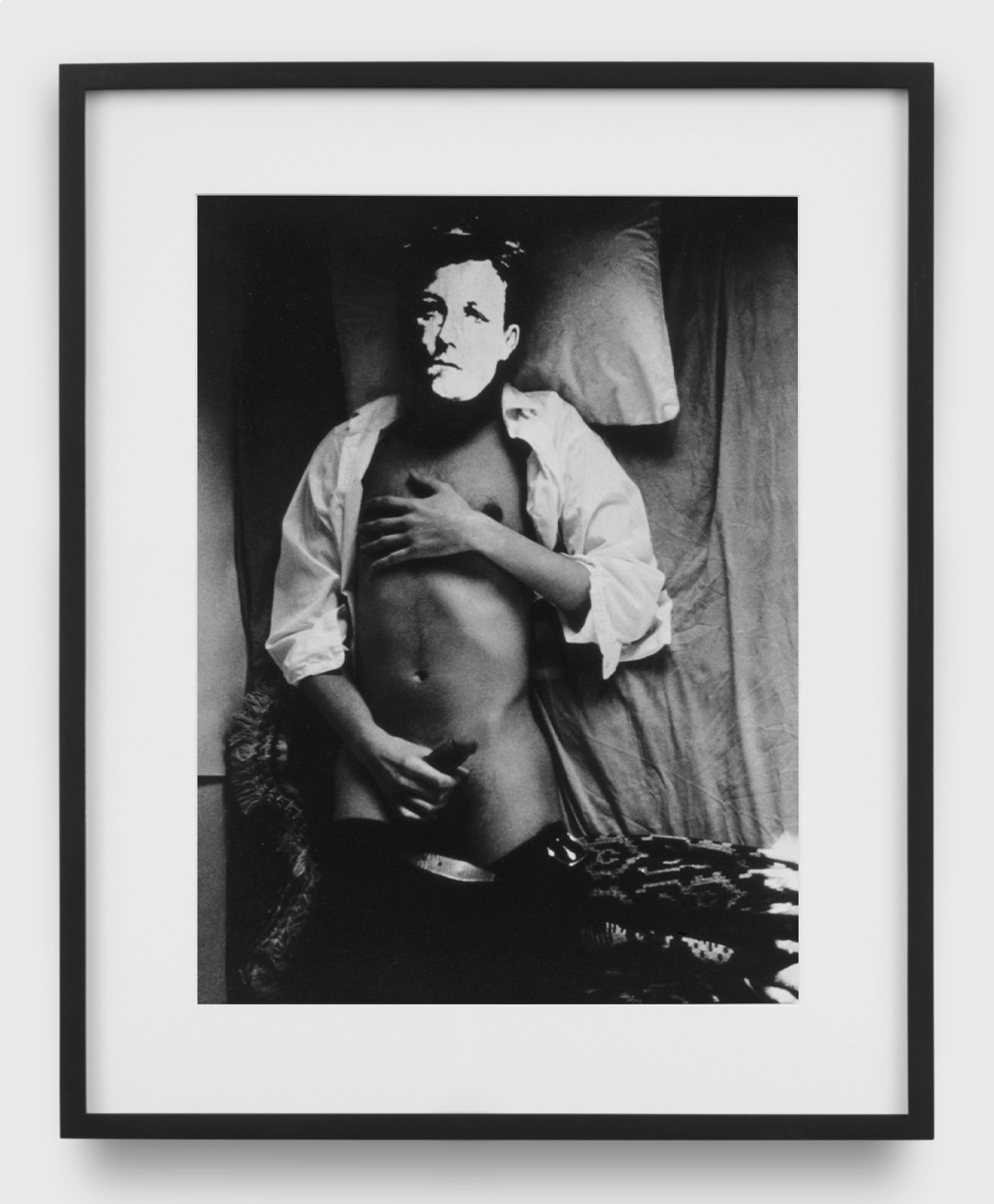

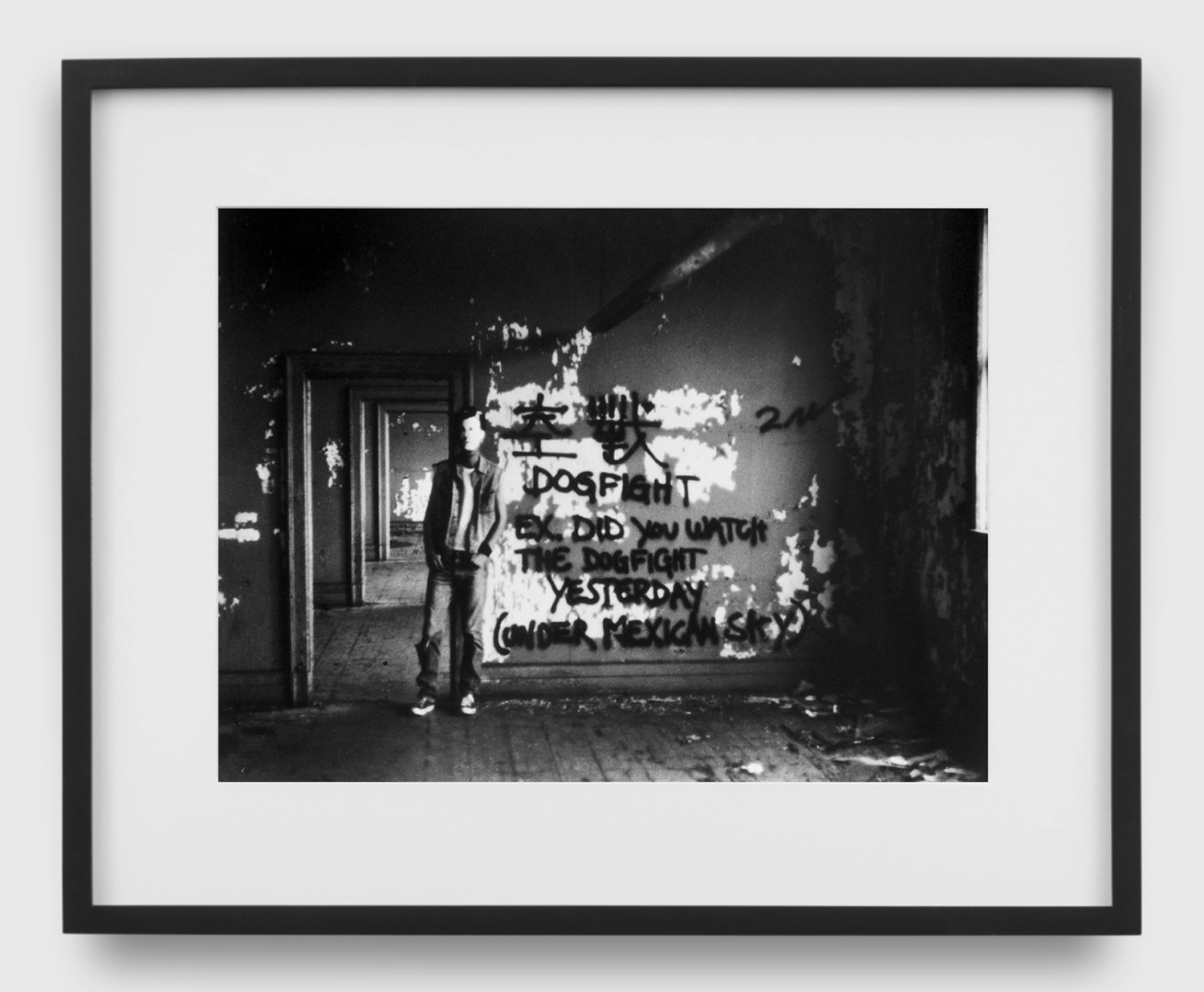

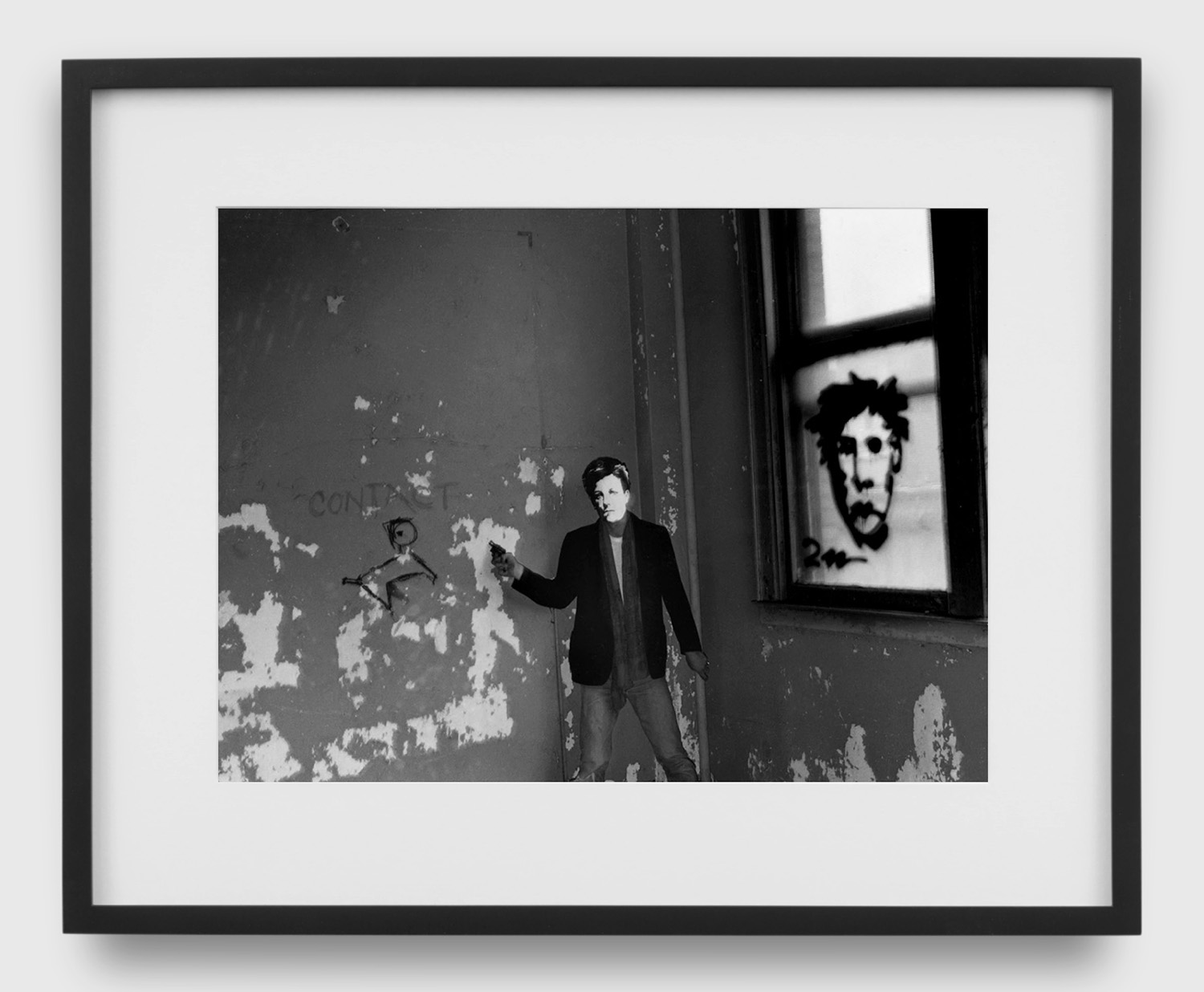

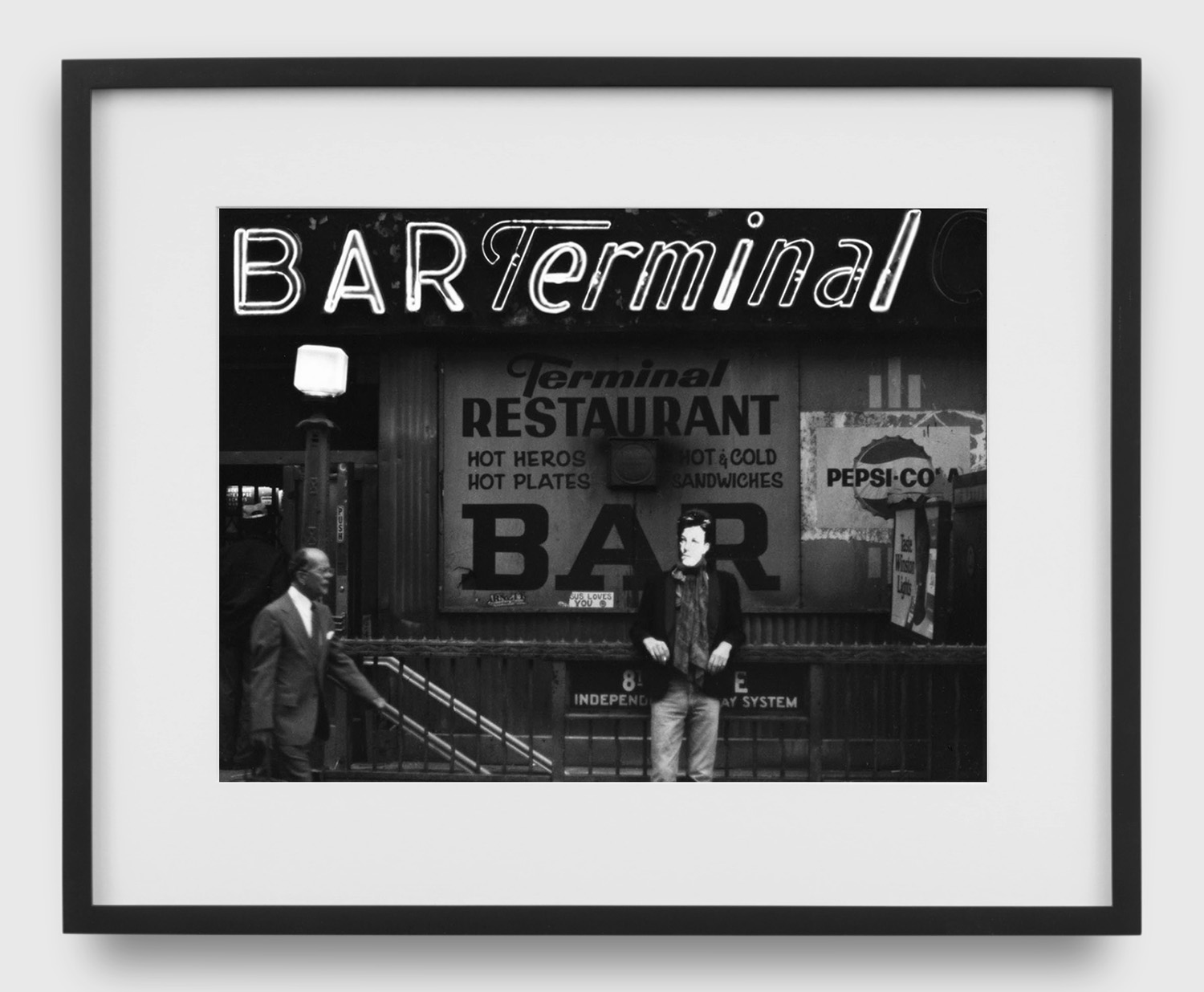

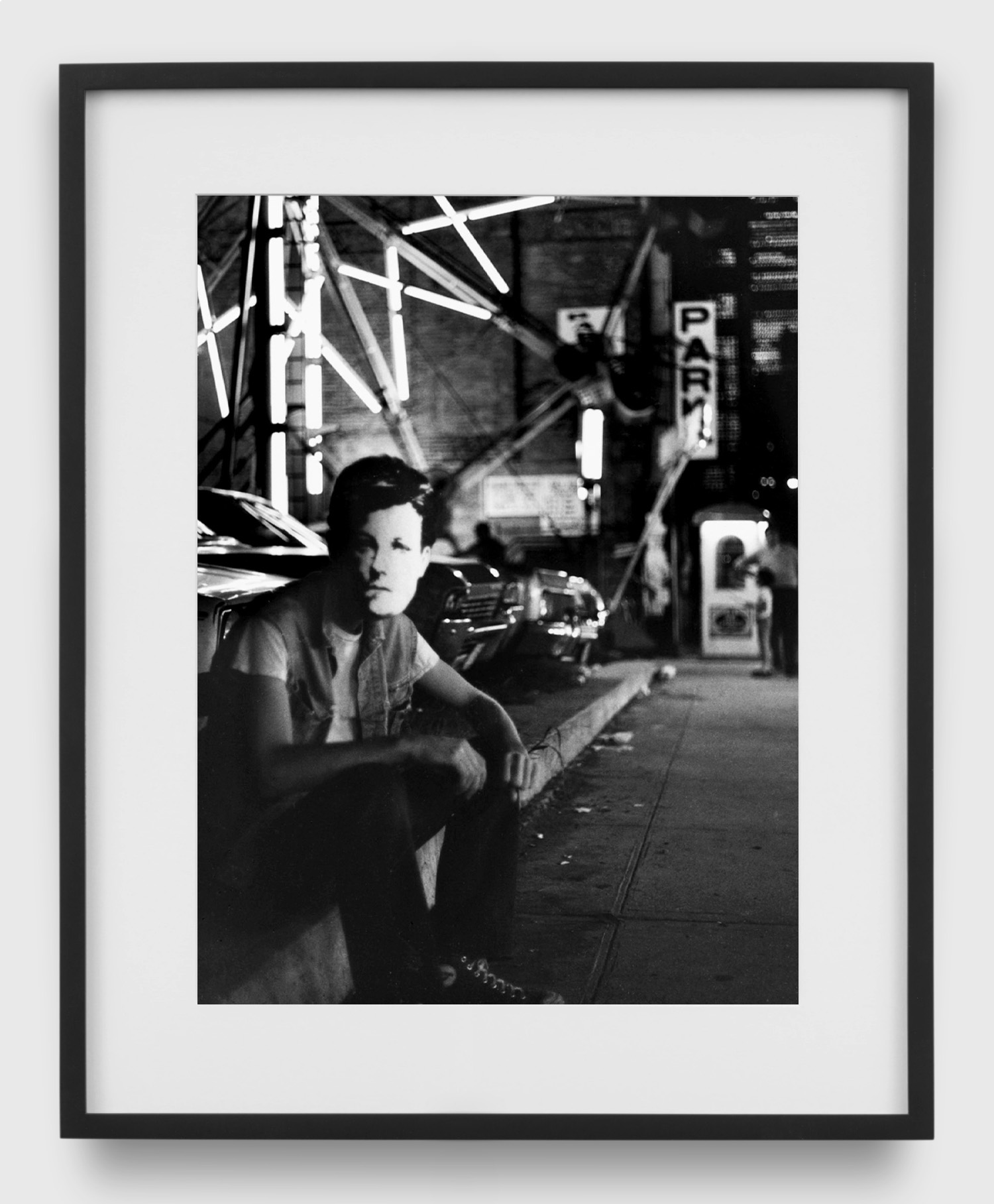

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

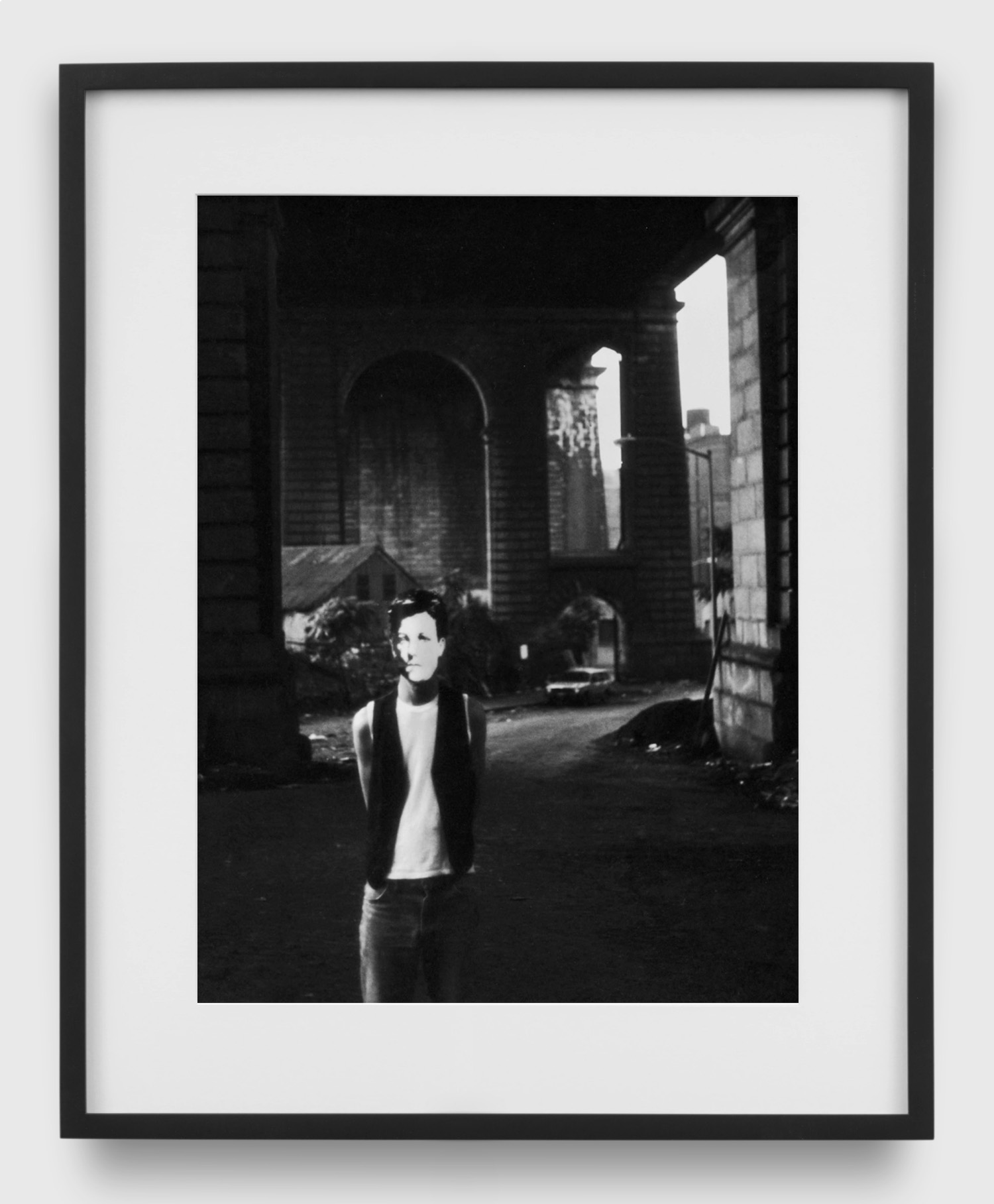

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 13 x 9.75 inches (each); Paper size: 14 x 11 inches (each)

(Image size: 33 x 24.8 cm [each]; Paper size: 35.6 x 28 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

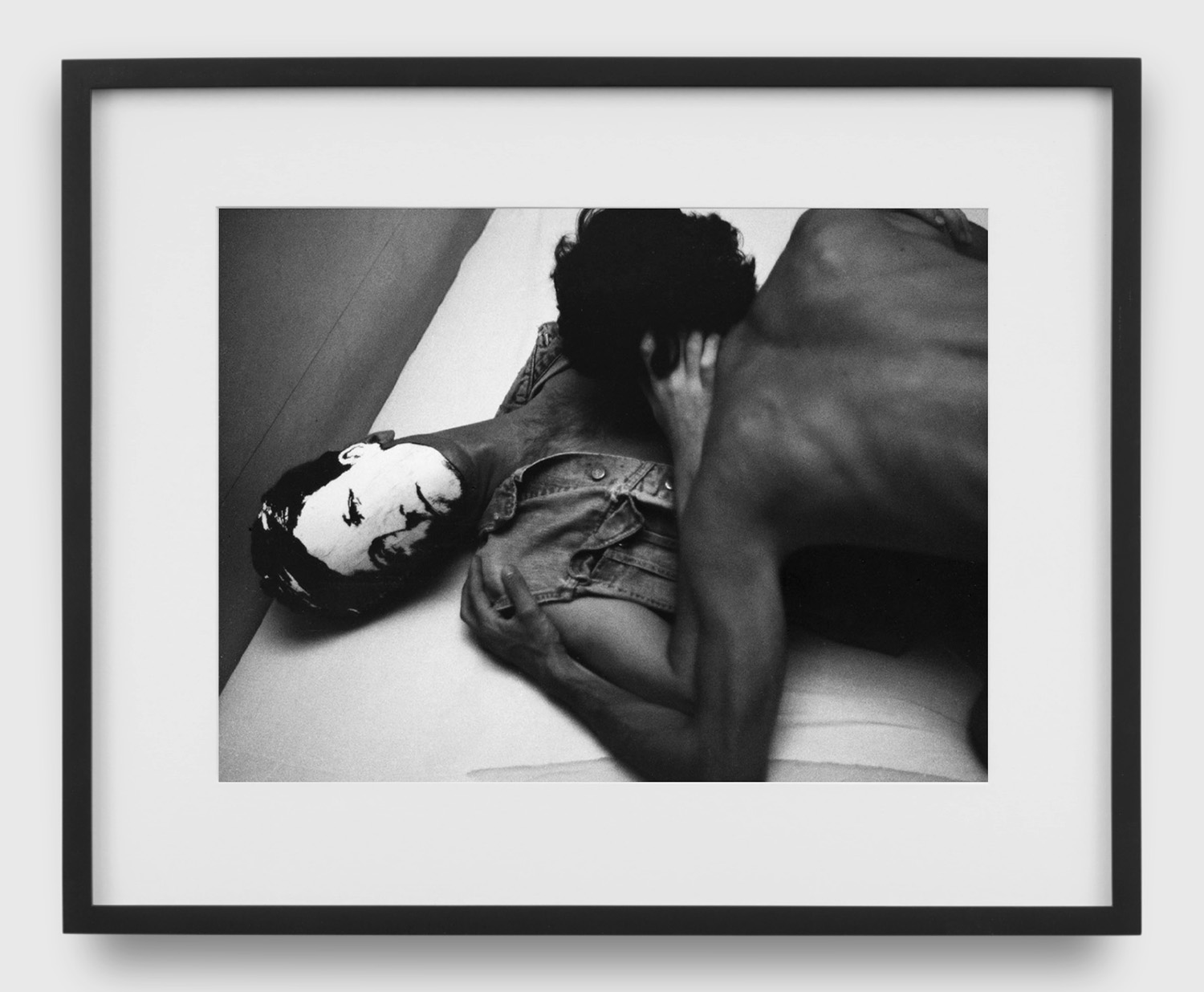

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 13 x 9.75 inches (each); Paper size: 14 x 11 inches (each)

(Image size: 33 x 24.8 cm [each]; Paper size: 35.6 x 28 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

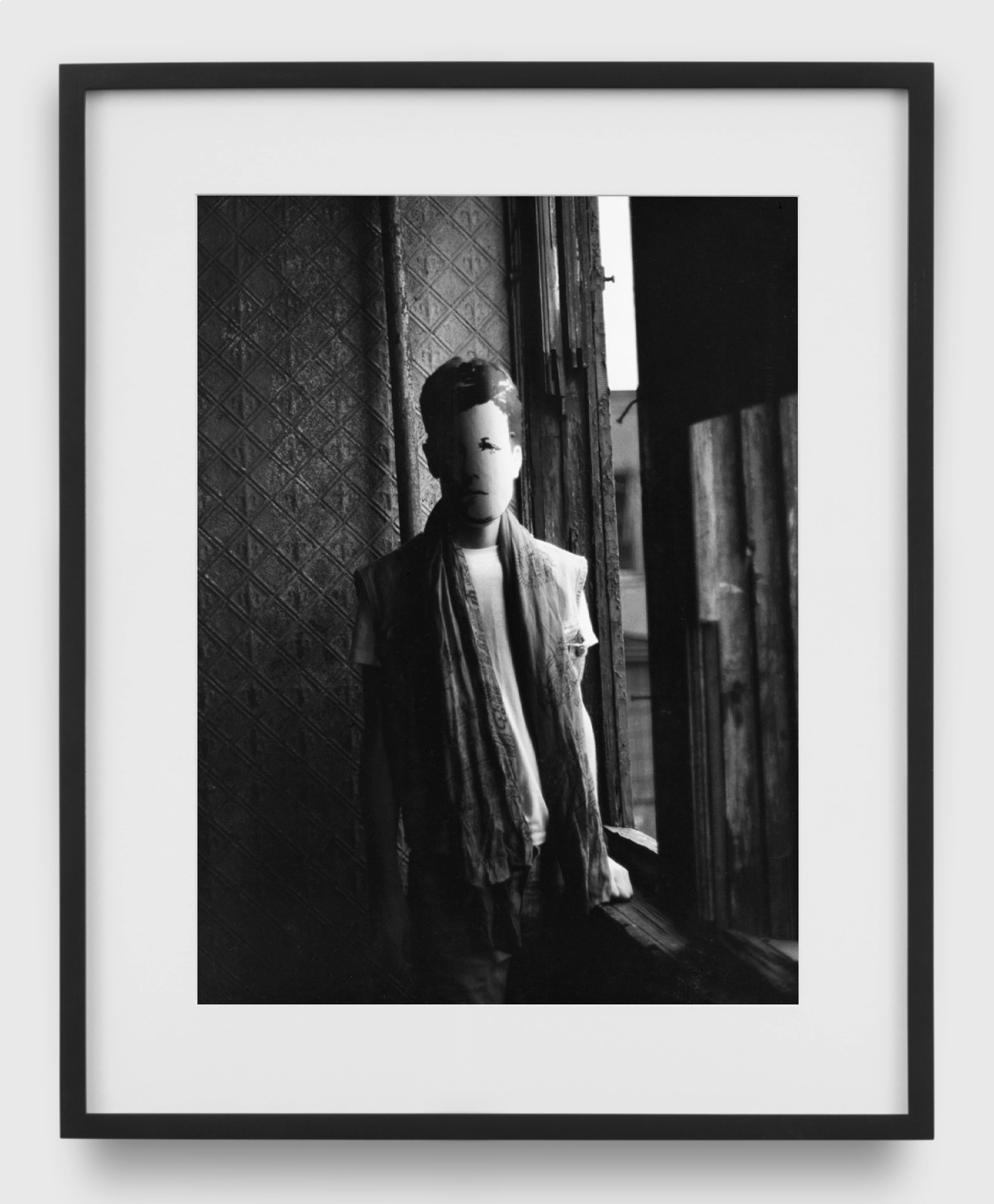

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 13 x 9.75 inches (each); Paper size: 14 x 11 inches (each)

(Image size: 33 x 24.8 cm [each]; Paper size: 35.6 x 28 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 13 x 9.75 inches (each); Paper size: 14 x 11 inches (each)

(Image size: 33 x 24.8 cm [each]; Paper size: 35.6 x 28 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 13 x 9.75 inches (each); Paper size: 14 x 11 inches (each)

(Image size: 33 x 24.8 cm [each]; Paper size: 35.6 x 28 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 13 x 9.75 inches (each); Paper size: 14 x 11 inches (each)

(Image size: 33 x 24.8 cm [each]; Paper size: 35.6 x 28 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 13 x 9.75 inches (each); Paper size: 14 x 11 inches (each)

(Image size: 33 x 24.8 cm [each]; Paper size: 35.6 x 28 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 13 x 9.75 inches (each); Paper size: 14 x 11 inches (each)

(Image size: 33 x 24.8 cm [each]; Paper size: 35.6 x 28 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 13 x 9.75 inches (each); Paper size: 14 x 11 inches (each)

(Image size: 33 x 24.8 cm [each]; Paper size: 35.6 x 28 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 13 x 9.75 inches (each); Paper size: 14 x 11 inches (each)

(Image size: 33 x 24.8 cm [each]; Paper size: 35.6 x 28 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 13 x 9.75 inches (each); Paper size: 14 x 11 inches (each)

(Image size: 33 x 24.8 cm [each]; Paper size: 35.6 x 28 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 13 x 9.75 inches (each); Paper size: 14 x 11 inches (each)

(Image size: 33 x 24.8 cm [each]; Paper size: 35.6 x 28 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 13 x 9.75 inches (each); Paper size: 14 x 11 inches (each)

(Image size: 33 x 24.8 cm [each]; Paper size: 35.6 x 28 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 13 x 9.75 inches (each); Paper size: 14 x 11 inches (each)

(Image size: 33 x 24.8 cm [each]; Paper size: 35.6 x 28 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 13 x 9.75 inches (each); Paper size: 14 x 11 inches (each)

(Image size: 33 x 24.8 cm [each]; Paper size: 35.6 x 28 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 9.75 x 13 inches (each); Paper size: 11 x 14 inches (each)

(Image size: 24.8 x 33 cm [each]; Paper size: 28 x 35.6 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz

Arthur Rimbaud in New York Portfolio, 1978-79/2004

44 framed gelatin silver prints

Image size: 13 x 9.75 inches (each); Paper size: 14 x 11 inches (each)

(Image size: 33 x 24.8 cm [each]; Paper size: 35.6 x 28 cm [each])

Edition #6 of 6

Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P•P•O•W, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

David Wojnarowicz and Jesse Hultberg

Excerpt from Beautiful People, 1988

Super 8mm film on digital video, b&w and color, silent (excerpt 2 minutes and 30 seconds)

Courtesy the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and P.P.O.W, NY, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles