- Source: THE BROOKLYN RAIL

- Author: Ksenia Soboleva

- Date: FEBRUARY 1, 2023

- Format: ONLINE

Eve Fowler: New Work

Eve Fowler, Florence Derive, 2023. 16 mm color film transferred to HD video, Duration: 11:25 minutes. Courtesy Gordon Robichaux NY and Morán Morán, Los Angeles. Photo: Greg Carideo.

In her beautiful book on the art of translation, Kate Briggs offers a compelling reason for a writer’s desire to write. “I write because I have read,” she states, quoting Barthes, reminding her reader that creativity does not exist in a vacuum. This simple thought resonates with me not only as a writer, but as a writer who often writes about other people’s work. To engage with the work of another, whether to praise or critique, is inherently a form of generosity. It means to be in conversation, to share a lineage, to touch each other. I imagine my words rubbing against the materials of every single artwork I read.

Perhaps this is precisely why I have found myself continuously drawn to Eve Fowler’s art, which often takes the work of others as its subject or its starting point. While Fowler’s career in 1990s New York was launched with photography—many will be familiar, for example, with her portraits of male hustlers in the West Village and on Santa Monica Boulevard—my first encounter with the artist was through colorful text pieces that repurposed the poems of Gertrude Stein. A queer icon whose own creative work has received less attention than her collecting and hosting practices, it is not surprising that Fowler should choose to bring attention to Stein’s poetry. Since the 2010s, Fowler has played with the poet’s words and presented the resulting text pieces through vernacular media, such as posters and billboards. Fowler’s investment in Stein is part of a larger commitment to highlighting women and non-binary artists, which is most poignantly illustrated in her films with it which it as it if it is to be (2016) and with it which it as it if it is to be, Part II (2019)—the title naturally taken from Stein’s poetry. In these films, Fowler captures women artists at work in their studios. The first centers her closest friends, such as A.L. Steiner and Nicole Eisenman, while the second focuses on the late career of artists like Harmony Hammond and Etel Adnan.

The exhibition of Fowler’s work currently on view at Gordon Robichaux shows us that her feminist pursuits are far from abandoned. Fittingly titled Eve Fowler: New Work, the solo show consists of a film, a series of collages, and a nine-channel video installation.

Upon entering the gallery, the viewer first encounters Florence Derive (2023), a film portrait of the eponymous French artist, projected onto the wall. For ten minutes, Derive quietly sits in her studio and gazes directly into the camera—at times revealing a gentle smile, at others withdrawing into a more pensive mode. A voice-over, read by Derive herself, tells the artist’s story of childhood and coming of age as a trans woman. It begins with recollections of meaningful moments she spent with her grandmother, listing all the things she was made curious about: hatpins, hammerhead sharks, hummingbirds. These observations come across as intensely poetic; after all, isn’t the list at the core of poetry? The blissful narrative, however, takes a turn when Derive starts remembering the coded homophobia and transphobia she faced. Emotionally abused by a high school teacher who hated her effeminacy, Derive was made sufficiently insecure about her potential for a “successful” future that she failed her classes and was expelled after the eighth grade. Finding enough community and confirmation at a new school to graduate, Derive shares how attending art school allowed her to fully find her sense of self. Derive recalls: “What came out of this introspection, first and foremost, was that my teacher was right. I was always a girl on the inside. And now I am one externally. There was never any divide or split. Rather, there was a long, slow reconciliation of my two halves.”

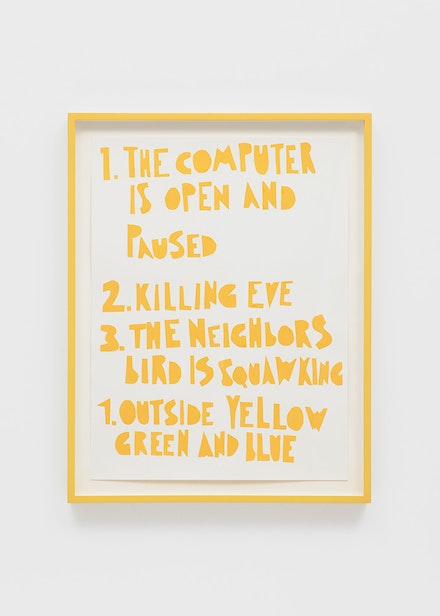

Eve Fowler, The computer is open and paused, 2022. Collage on paper in artist’s frame, 24 x 18 inches. Courtesy Gordon Robichaux NY and Morán Morán, Los Angeles. Photo: Greg Carideo.

Fowler’s portrait of Derive is a tender meditation on how lived experience is translated into language. The clever decision to record Derive’s text as a voice-over, rather than having her read it out loud in front of the camera, hints that it is Derive’s memory that speaks.

Moving into the next room, one finds a series of seven collages. Cut irregularly from colored paper (yellow, green, and blue), letters cluster up into words that in turn form lists. While the expectation of those familiar with Fowler’s work might be that these are fragments of Gertrude Stein’s writing, they are actually Fowler’s own words and observations. Casual yet lyrical, the references to LA, cars, and birds gain more context when viewed from Fowler’s perspective—not to mention the phrase “Killing Eve,” an allusion to the television show that finished last year. While these lists do not have the same playful rhythm of Stein’s poetry, Fowler’s words draw out tenderness from the mundane and give us a rare glimpse into the artist’s consciousness.

Eve Fowler, Labor, 2023. 9-channel video installation, Dimensions variable with installation, 20 videos, each 3 minutes. Courtesy Gordon Robichaux, NY and Morán Morán, Los Angeles. Photo: Greg Carideo.

The second, smaller gallery space of Gordon Robichaux houses the nine-channel video Labor (2023), installed over nine monitors that are hung on three vertical poles. Set against a striking view over the city, the videos reveal vibrant colors and textures, all structured by the movement of hands. Shown here are twenty women and non-binary artists, most of them friends of Fowler’s, filmed in the process of making their work across a range of media. Contrary to Fowler’s earlier films capturing artists, this one is entirely focused on hands. I recognize the hands of Siobhan Liddell and Leilah Babirye, whose artmaking I’ve had the pleasure of witnessing myself. I manage to spot Liliana Porter and Reverend Joyce MacDonald, among others, through the work they’re making. I cannot help but read this close observation of hands as deeply erotic, as hands hold particular significance in lesbian and queer culture. Sitting in the darkened room, I become mesmerized by the gestures of fingers, the brilliant hues, the shapes that emerge.

The way in which Fowler pays attention comes with a seemingly effortless grace that conveys the sincerity of existing in the world as an artist. Studying others, Fowler is perhaps searching to find herself. There is a humility in her foregrounding of other artists, a kind generosity. Yet there is also a degree of reserve, a distance and restraint. Fowler is there, of course—particularly in the collages—but we don’t get to see her. We don’t get to see her hands cutting the paper; we don’t get to see her eyes gazing into the camera. And so that which is missing becomes, inevitably, the object of desire.