- Source: Émergent Magazine

- Author: Valeria Biamonti

- Date: Issue Six

- Format: Print

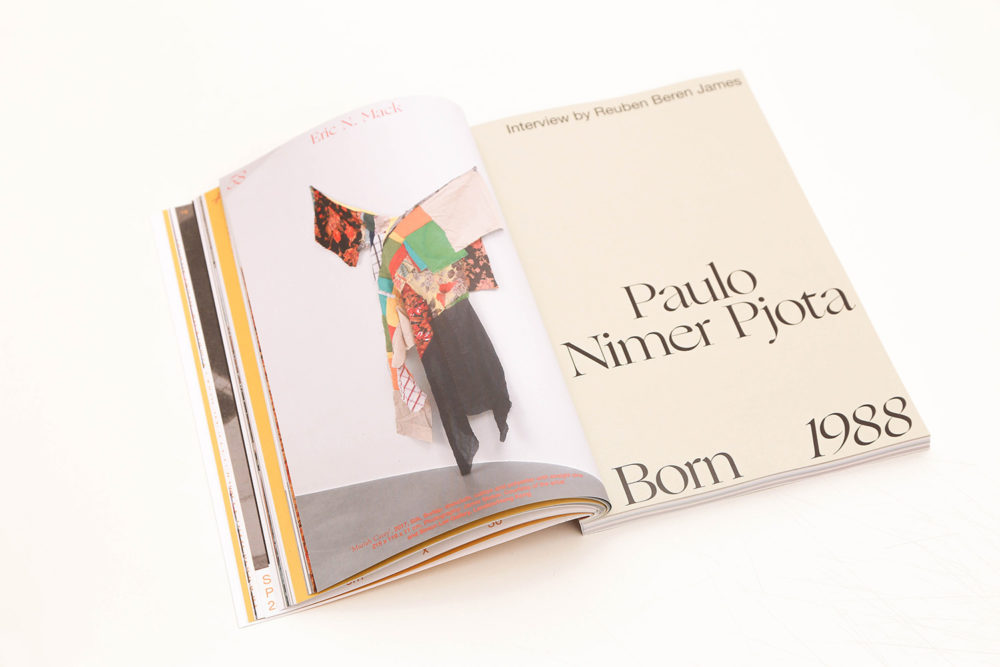

Eric N. Mack

Interviews

The term ‘painting’ has always been quite close to your practice, and to how it is interpreted. How do you experience the relationship between your work and painting?

I think the work comes from citing problems that come from painting. Questions in regards to depth and materiality, proximity. The physical intimacy of a viewer. Also, issues like that of abstraction–whether a painting can really hold emotional meaning for the viewer…I began with Belgian linen, cotton, standard kinds of material surfaces to paint on, transform further by switching these conventional surfaces out and find those surrogates that connect with life differently. I felt like the most engaging manner I could deal with surface, and all of these questions had to do with the sculptural dimension.

In the last decades, there has certainly been a shift in how the medium of painting can be understood and experimented with, expanding the field beyond the confines of the canvas. How would you like your practice to contribute towards new possibilities in painting? How do you relate to painting’s past?

I have always connected to my sense of history and precedent. I think of the Blinky Palermo cloth pictures as a poignant moment for me, which brought up important questions. ‘Is this a readymade? Is this an abstraction? Is this a landscape?’ Particularly, ‘How is this an object–beyond just a simple picture?’ I connect with attitude through gesture. I imagine an object’s presence in a specific space and how this presence changes the space’s overall dynamic and understanding.

Found images and objects play a fundamental part in the poetics of your practice. I find it fascinating the way you bring objects together, objects that have previous histories and that suddenly become something else.

I am a formalist. A lot of my connection to the work has to do with visual phenomena, the composition, or the attempt at finding form. There are ways I feel challenged by form. When, for example, I see whether it can contort itself into something else. You know, by the simple means of cutting, folding, re-stitching…Towards the end of the process, the lasting meaning shifts come.

Do you conceive the viewer’s engagement with your work early in the process? Do you have specific expectation of the viewer?

I think a lot about the viewer. I think the viewer isn’t very different from me. I feel like there’s…a want for complexity. I want something to be able to appeal to anyone but at the same time to be able to speak its own language. Sometimes, when things speak so distinctly, there isn’t any exclusion. I like contradiction in a work. There are many different approaches, which opens up the conversation. There are so many expectations when the art viewer comes into the gallery or museum. I like reducing those components to more simple forms, more bodily forms, allowing there to be a kind of reward in examining the artwork. You know, you look closer, and you see something else. From afar, you may not get it completely: When the question about the work’s nature is meant to be asked.

How important are the titles of your works?

It’s its own process, I think. There are times when language comes into play really specifically. I like to use jargon, a word that pertains to specific kinds of labour, or subdivisions, regional slang, using dialect, which presents opportunities to give voice and emotion to art objects. Sometimes the work is made of readymade materials and surfaces, and often the titles end up being readymade. They come from lines of songs, or the name of local businesses that I walk past every day, a friend’s baby…They can all be fair game and talk about life.

Do you feel like your work is autobiographical?

It is unavoidable. The compelling thing is empathy involved in the process of abstraction.

I can personally sense a performative element in your work. Not in the sense that the work itself is performance. It’s more the visibility of the process in the finished piece, the installation of the work, its relationship to architecture, which are performative…

I like that the moving blankets have a kind of installation element. Their thick-ness and materiality… They were almost able to contain walls-that the fabric could be attached to the gallery walls would allow the space to be affected in several ways. The gallery could become more insulated by each work installed. Many of those blankets buffer sound in music studios. Outside their use as a protective blanket for art objects and furniture, there are other uses that I am interested in that the viewer happens upon. A lot of the performance I am interested in is a bit invisible. It is evident through the gestures of placement, the use of space, anticipation, and rhythm. Allowing the fabric to drape in a precise way… Having to reach to the ceiling and also to reach low, near the ground…Space is then able to be activated by the placement of works. I think that kind of physical stretch is essential.

How much does the installation process of the work influence its final form? How do you prepare a show?

It depends on the works. I think about focal points beforehand. What you see as you enter into the room, and what is the last thing you see. It ends up being like a vignette, several vignettes. Untreated fabric can be difficult material to work with. Unlike the traditional primed canvas, the artist is not in complete control when it comes to fabrics’ undisciplined, ‘floating’ character.

Do you see this as a challenge or as an opportunity to let chance seep into the work?

Both things have to happen. I usually have works that have to be attached to the wall precisely, and other artworks that would be moved around many times, which are a lot more about a degree of improvisation. But I work with image. Again, I work thinking about the lasting image of a work-the way something drapes, for example. I measure the width of the draping, and I make sure that it can be replicated. Still, there is a degree of improvisation that I think is very important for a work to feel like it can live in the space.

What about more site-specific works, like Halter, the Missoni commission for the outdoor biennial Desert X?

I made many drafts for that piece. I had never done anything at that scale. A lot of my process has to do with accumulated lessons, formal lessons. The way that something could be distributed, for example. Or an understanding, which came from previous work experience, of the way that fabric acts in mass. I wanted to restage prior works with entirely different fabrics, scaled up. It was vital for me to have this concrete proposal of what was going to happen. In this case, there was less room for improvisation. I am grateful we were able to use Missoni fabrics; it came from a recent archive. I was honoured to be able to work with this legendary brand. The quality of the textile was outstanding–how durable and flexible. One of the main stipulations was that the fabric should be translucent. The knit was perfect for that. So it was not opaque, but rather a kind of screen to look through.

Where do you normally source the fabric you use?

My go-to place in New York is Mood Fabrics, a famous fabric store from Project Runway. But when I travel, I generally go to local fabric shops. In Milan, for example, it was amazing. They have scrap piles of fabric, and you weigh it. It was perfect for me since I use fabric reminisces more than anything. I usually only need one or two yards to create. I also go to the Salvation Army, vintage shops…I’m getting better at eBay, so I’m doing more of that, but it is still difficult since you can’t touch the fabric, and you can only rely on the picture.

What’s your view on sustainability of the textile industry?

It is an important topic, especially in fashion, because there is so much over-production and waste. I think it is crucial that is has become more of a focal point in the industry. Like, you have significant brands that allow that to be central, their pitch for the season. It is entirely reflective of issues like climate change. And also on a more humanitarian level, with regards to factories and labour, allowing people, the workers to have a voice.

Do you think the way you work can say something about it? Could it potentially bring awareness?

I think the way that I work ends up being a model for other forms of making. The fact that the work still holds elegance and mystery and the fact that it can communicate with space. I feel like I see a lot of those references in the fashion industry. You know, looking at the patchwork quilt as a model, which ends up being revisited by many brands… It has a direct correlation to sustainability. Also thinking about the quilters from the American South, women that worked in factories that produced denim jeans and corduroy, who then could do with the reminisce of the fabrics and ended up making beautiful quilts from them. There’s even an opportunity to go beyond sustainability–a kind of a new life, what is going to happen after the regeneration.