- Source: THE NEW YORK TIMES

- Author: MARTHA SCHWENDENER

- Date: JUNE 06, 2019

- Format: DIGITAL

Encountering the ‘New Order’ at MoMA

The blind spots and new possibilities of the technologies we love (and hate).

Josh Kline’s “Skittles” (2014), left, and Ian Cheng’s “Emissary Forks at Perfection” (2015-16) in the show “New Order: Art and Technology in the Twenty-First Century” at the Museum of Modern Art. (Credit The Museum of Modern Art; Jonathan Muzikar)

What differentiates the work in “New Order: Art and Technology in the Twenty-First Century” from much of the art elsewhere at the Museum of Modern Art is that the objects here are made with technologies most of us already know and love (or hate). Flat screens, computer interfaces, video games, digital animation, 3D-printing and photography are transformed here into sprawling installations, canny video art or interactive sculptures.

The work in “New Order” is drawn entirely from MoMA’s collection and organized by Michelle Kuo, who became a curator at the museum last year after serving as editor in chief at Artforum magazine for seven years. The exhibition is meant to demonstrate how much of the technology we think of as invisible — waves, wireless or abstract code — is still rooted in physical objects. And the artists, with varying success, are intent on showing us technology’s blind spots and limitations, while opening up new possibilities for its use.

Much of the art here draws a line in the sand between technology’s use in design and gadgetry. Some of the more compelling works consider how, for example, technology augments the human body, promising better health, longevity or happiness but rarely delivering on the promise. Josh Kline’s “Skittles” (2014), a large commercial refrigerator at the entrance, is stocked with smoothies in invitingly minimalist packaging. Approaching the refrigerator, however, you see the ingredients listed and they include indigestible components like chopped-up credit cards, magazines and sneakers, or a toxic cocktail mixing cold medicine, energy drinks, pain relievers and psychiatric medications.

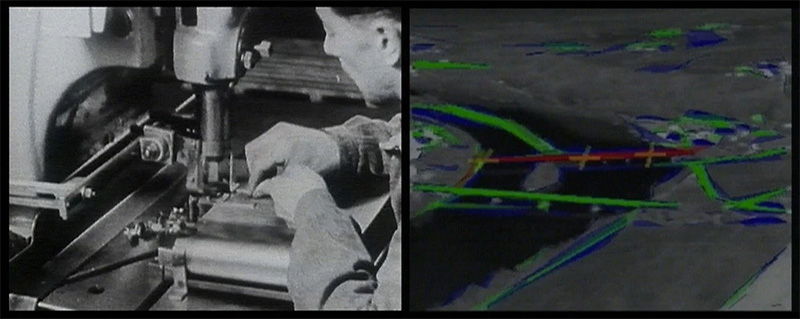

Harun Farocki’s “Eye/Machine I” (2001), a two-channel video installation re-edited to single-channel video. (Credit The Museum of Modern Art)

Around the corner, you can jump on two exercise machines and activate Sondra Perry’s workstation videos that show her avatar, as well as digital images of J.M.W. Turner’s “The Slave Ship” (1840). The juxtaposition injects a discussion of the black body in the African diaspora that’s often missing in many technology forums.

Beyond that is Jacolby Satterwhite’s neo-psychedelic, gay- and sex-positive animation featuring candy-colored bodies dancing and morphing into other beings, as well as Anicka Yi’s somewhat less successful series of vitrines with nickel-plated pins rusting in a bath of ultrasonic gel, simulating human blood. (Ms. Yi’s videos, not on view here, engage more effectively than her sculptures with biotechnology and its effect on all species.)

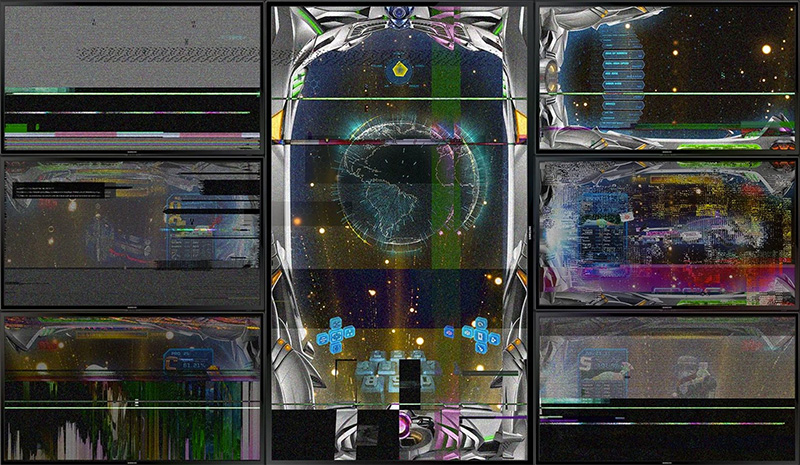

Tabor Robak’s “Xenix” also shows GPS images and weapons, reminding you of how some technologies in our everyday lives developed out of military systems. (Credit The Museum of Modern Art)

Two of the most significant works, for me, were made a dozen years apart, during a time when imaging technologies developed at breathtaking speed. Harun Farocki’s “Eye/Machine I” (2001), a now-classic two-channel video, ultimately considers what will happen when war is waged by “intelligent” machines that read images and make decisions. Tabor Robak’s “Xenix” (2013) is a slick and seductive seven-channel work that looks like a blown-up version of your smartphone or desktop and displays such comically banal details as the weather and the contents of a refrigerator. It also shows GPS images and weapons, reminding you of how some technologies in our everyday lives developed out of military systems and the many ways people sacrifice their privacy to join social media or use a Google map. Where Mr. Farocki’s work pairs images in a thoughtful, more meditative way, Mr. Robak’s reflects the full-force scramble for our attention underway every time we glance at the internet or pick up a device.

Rather than optimism or celebration, “New Order” ripples with the menacing effects and potential pitfalls of new technology, but it could use a larger dose of global thinking. It could have exhibited a greater connection between technology and the physical world with a bevy of recent films and artworks, seen elsewhere, that have highlighted the detrimental effects of manufacturing and electronic waste on the environment. For instance, films about dumping e-waste in Africa has become a genre in itself. As opposed to representing work focused mostly on gadgetry and design, with body-enhancing products, from pharmacology to smoothies, a show about technology and the physical world might also acknowledge the end result of technology-related manufacturing and pollution and their global effect on all of us.

Jacolby Satterwhite's "Country Ball 1989-2012" (2012). (Credit The Museum of Modern Art)