- Source: HYPERALLERGIC

- Author: Annabel Keenan

- Date: SEPTEMBER 25, 2023

- Format: DIGITAL

Ecology From the Perspective of the Marginalized

Humane Ecology at the Clark Art Institute asks viewers to consider different interpretations of nature, including those of people who have been marginalized, silenced, and erased.

Installation view of Humane Ecology: Eight Positions at the Clark Art Institute. Pictured: Carolina Caycedo, "In Yarrow We Trust" (2023), acrylic on canvas, 144 x 240 inches (courtesy Clark Art Institute, photo Tucker Bair)

Nestled in the mountainous Berkshires, the Clark Art Institute has a close relationship with the natural world. Inside the galleries, visitors can see miles of hiking trails and woodlands that weave through the 140-acre campus. Countless works from the collection feature nature, from romanticized and sublime to cultivated and colonized. Broadening a Western, exclusionary perspective on human and nonhuman relationships with nature is the Clark’s latest contemporary exhibition, Humane Ecology: Eight Positions. Featuring new and recent works across disciplines by artists of diverse backgrounds, the show asks viewers to consider different interpretations of nature, including those of groups of people who have been marginalized, silenced, and erased altogether.

Playing on the term human ecology — the study of humans and the natural and built environment — the exhibition eschews a human-centric, hierarchical view for a more nuanced approach encompassing all organisms. The “eight positions” of the title point to the artists: Eddie Rodolfo Aparicio, Korakrit Arunanondchai, Carolina Caycedo, Allison Janae Hamilton, Juan Antonio Olivares, Christine Howard Sandoval, Pallavi Sen, and Kandis Williams. Some works engage with the theme more directly, such as Sen’s garden installed outside the museum. Comprised of plants from India, where the artist grew up, the species thrive in extreme conditions, specifically heat and drought. Their ability to grow at the museum reflects climate conditions new to the region. Other works, like Williams’s photo collages with glimpses of Black performers (dancers, models, sex workers) on artificial plants, address how Black individuals are often fetishized in popular culture, and offer a more conceptual approach to the theme.

Los Angeles-based Aparicio’s large latex rubber castings of Ficus trees greet visitors to the exhibition. The trees, introduced to LA in the mid-20th century, have invasive roots that damage sidewalks and have created debates over who should maintain (or remove) them, and how. The work raises complex questions surrounding the terms “native,” “introduced,” and “invasive” species, a theme also addressed in Sen’s garden. With colorful, anthropomorphic shapes — arms, legs, and contorted bodies — on the backside of the latex casting and the reference to Salvadoran crime policies in the title, “Mano dura,” Aparicio links the work with conversations on immigration, as the controversial policies were enacted to fight gang-related violence that led many people to seek refuge in the US in the 1990s and early 2000s. With the Ficus, Aparicio more broadly considers the treatment of Central American migrant workers who arrived around the same time as the trees and were eventually deported.

Installation view of Humane Ecology: Eight Positions at the Clark Art Institute. Pictured: Allison Janae Hamilton, “Untitled (White Ouroboros)” (2023), ASA filament, paint, resin, 42 x 28 x 8 inches (photo Annabel Kennan/Hyperallergic)

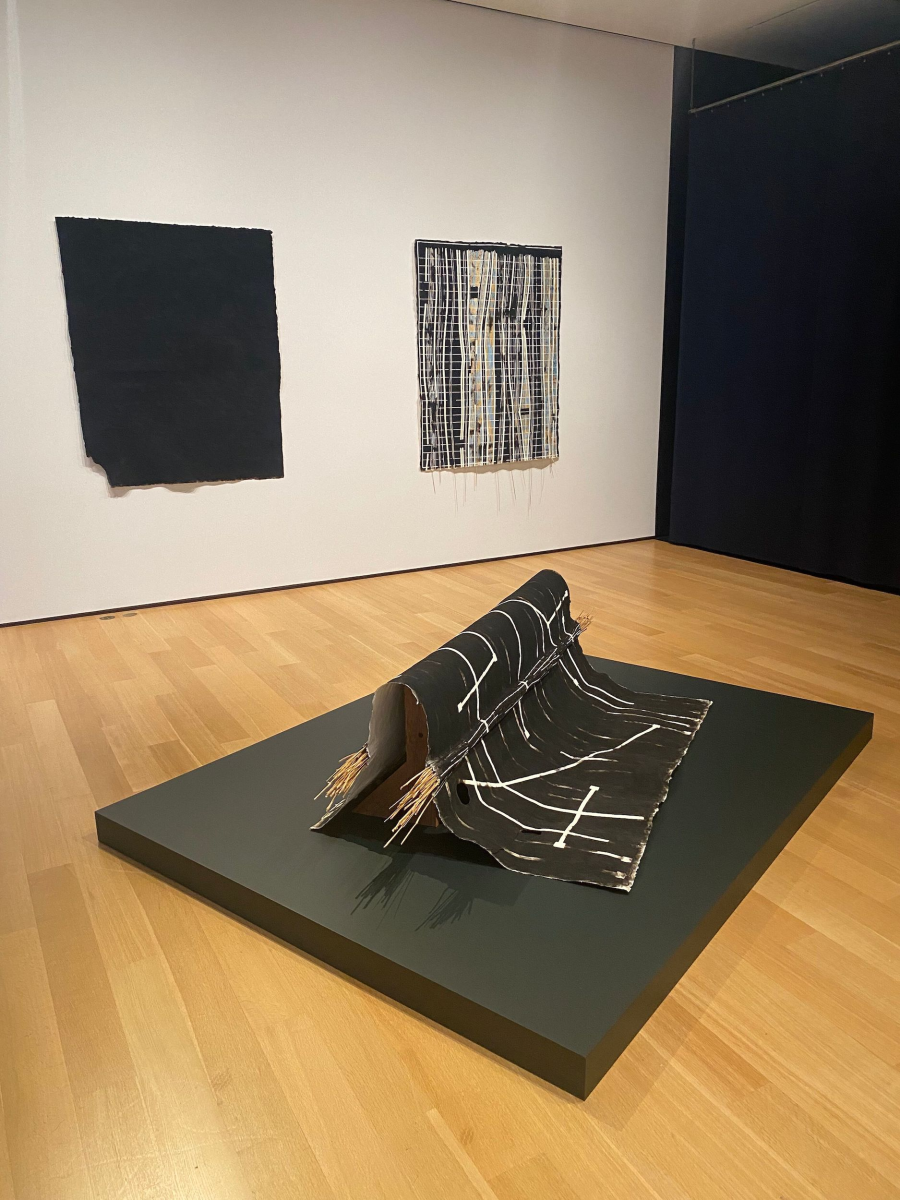

Nearby are Howard Sandoval’s soot drawings and sculptures on handmade paper embedded with bear grass stalks and seeds. The artist’s choice of bear grass, a material used in Native American basket weaving, speaks to her heritage. Scorching select parts, she references the Indigenous practice of using controlled burns to prevent forest fires. Ancestral knowledge and environmentalism are also at the core of Caycedo’s work, which pays homage to community leaders and Native elders, often female, who care for the natural world. She also depicts medicinal traditions of the Mohican people native to the land the Clark now occupies.

Howard Sandoval’s scorched works recall the wildfires that spread annually and with increasing devastation across the West Coast. When she created these pieces, the idea of a smoky, amber sky would have been considered a West Coast problem, but as smoke from the recent Canadian wildfires filled the Northeastern US, the issue took on local significance. While the artist could never have known her work would do so, she illustrates how an environmental concern new to one community can have a deep history in another.

Howard Sandoval’s pieces mark a timely link to the past, present, and — most likely as the effects of climate change worsen — future of Northeastern skies. Hamilton’s alligator sculptures outside the window represent another potential timeline. Biting their own tails in an ouroboros symbol of the infinite cycle of destruction and rebirth, the alligators are installed on platforms as if sitting in the dense woods. Native to Hamilton’s home of Florida, the animals are out of place in New England, but as water temperatures increase in the South and the Northern climate becomes balmier, perhaps there could be a future where they inhabit the forests. Pointing to the legacy of racialized imagery of alligators, Hamilton draws a parallel between their climate migration and Black communities that have historically endured the effects of environmental crises.

This relationship between marginalized communities and nature is an undercurrent throughout the show. The unknown and silenced repercussions of human behavior, from capitalism and colonization to environmental destruction, are brought to the fore, as are the beings who cultivate and care for the natural world. As the climate shifts and visitors’ relationships with nature change, their understanding of the interrelation of all organisms, including those overlooked, can — and should — evolve.

Installation view of Humane Ecology: Eight Positions at the Clark Art Institute. Pictured: works by Christine Howard Sandoval (photo Annabel Kennan/Hyperallergic)

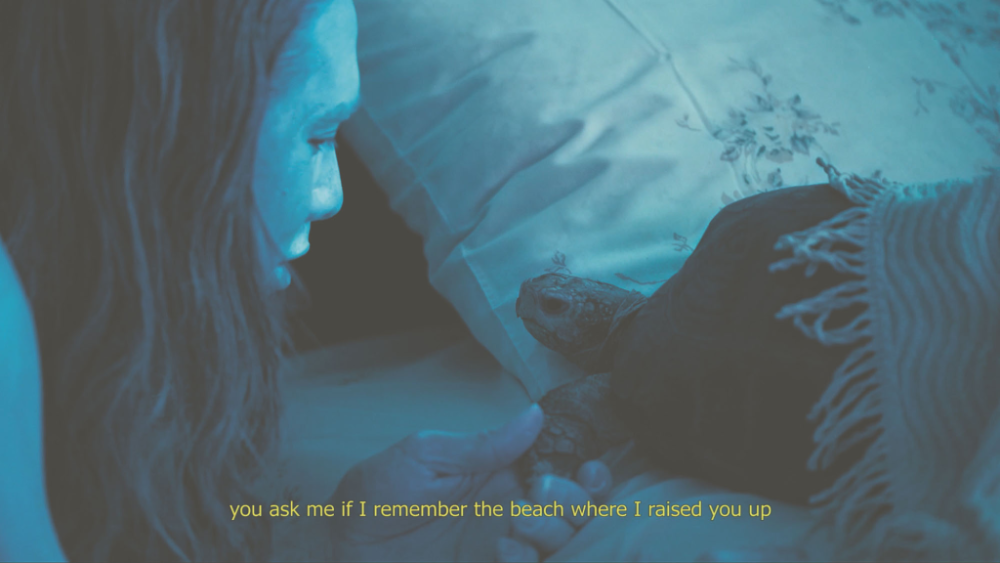

Korakrit Arunanondchai, “Songs for dying” (2021), single-channel HD video, color, sound, 30:18 minutes (courtesy the artist; Bangkok CityCity Gallery; Carlos/Ishikawa, London; C L E A R I N G, New York/Brussels/Los Angeles; and Kukje Gallery, Seoul)

Installation view of Humane Ecology: Eight Positions at the Clark Art Institute. Pictured: works by Kandis Williams (photo Annabel Kennan/Hyperallergic)

Installation view of Humane Ecology: Eight Positions at the Clark Art Institute. Pictured: works by Carolina Caycedo (courtesy Clark Art Institute, photo Tucker Bair)

Installation view of Humane Ecology: Eight Positions at the Clark Art Institute. Pictured: Pallavi Sen, “Experimental Greens: Trellis Composition” (2023), seeds, plant starts, soil, compost, rope, fasteners, ceramics, plaster, pigment, glass, pine, twine, irrigation, seasonal rain, sunlight, sticks, 46 x 19 feet (courtesy Clark Art Institute, photo Tucker Bair)