- Source: Frieze

- Author: Evan Moffitt

- Date: April 28, 2021

- Format: Online

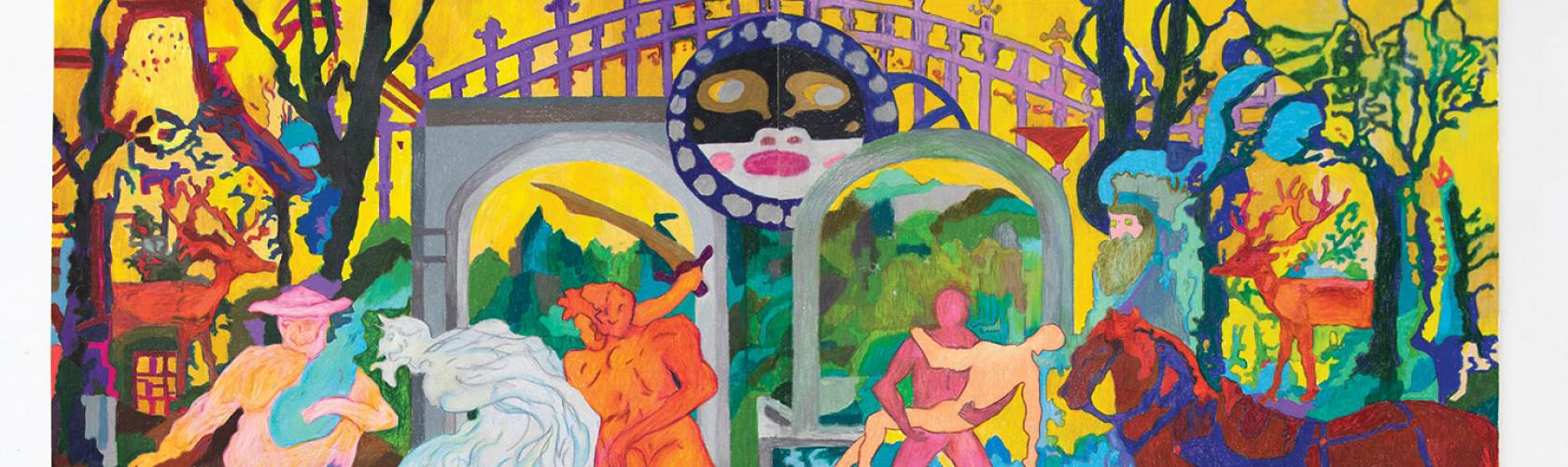

Dreaming on the Dancefloor with Raúl de Nieves

The artist’s exuberant sculptures and paintings, drawn from religious icons and club culture, are emblems of a changing New York

One night in 2014, the artist Raúl de Nieves dreamt he was standing on the edge of a cliff, with his mother by his side, urging him to jump. He shared the dream with a friend, the composer Colin Self, who’d had one very similar, inspired by the Fool card from tarot. Numbered zero, the Fool is the alpha and omega of tarot, marking both the beginning and end of a symbolic journey through the deck. Dressed like a harlequin, he walks towards a precipice with a dog at his heels, blissfully unaware that he might fall. Far from symbolizing ignorance, however, the card signals an openness to wonder and play. Only when we let go of our fears, the Fool suggests, do we become ready to learn what life has to teach us.

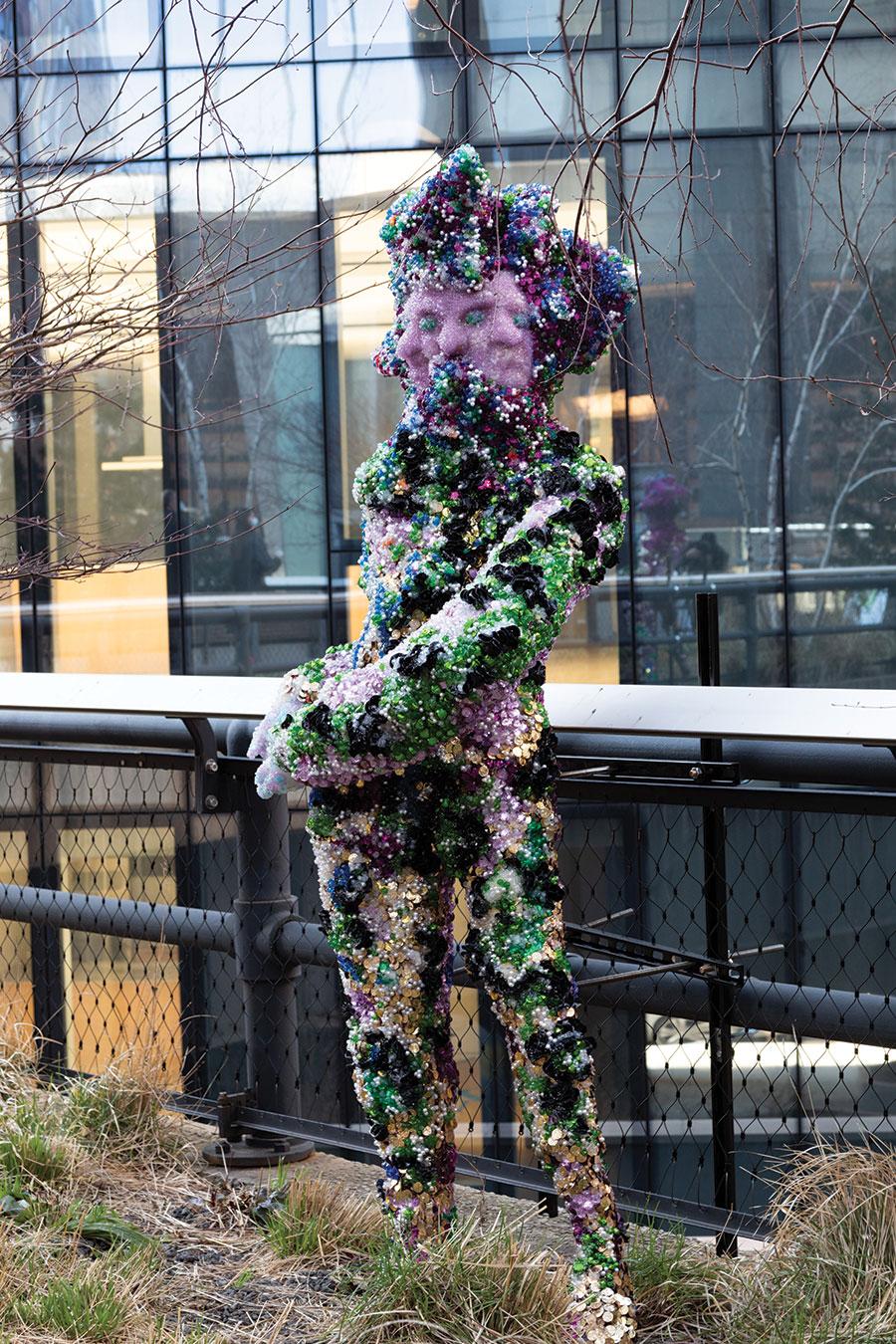

Fine Guardian, vintage military suit, sequins, metal bells, threads, glue, cardboard, plastic beads, tape, trims, mannequin, dimensions variable. Unless otherwise stated, all images courtesy: the artist, Company Gallery, New York, and Fitzpatrick Gallery, Los Angeles and Paris

In November 2014, De Nieves and Self staged The Fool – an hour-long opera for four soloists, a 15-member chorus and an instrumental quintet – at Issue Project Room, a performance space in a former Brooklyn bank. For the set, De Nieves constructed a pair of monumental doors with the Fool card designed in rhinestones across them. Self’s score drew on Gregorian chant, embellished with a Klaus Nomi-like falsetto. The libretto follows a child who jumps into the ocean and drowns, before coming back to life as an old woman, played by Self. Again, this ‘Fool’ finds herself on the brink of death, only to be encouraged to take a leap once more. De Nieves, as her loyal dog, reminds the Fool that her legacy will be celebrated after her passing. Each ending, we’re told, is also a beginning.

When I first met De Nieves in late 2015, he was a fixture of queer nightlife in New York. He was easy to spot from a distance, typically dressed in an oversized poncho or patterned sweater, with a brightly dyed, faux-fur coat and ribbons in his braids, like a cross between Frida Kahlo and Pebbles Flintstone. His raucous laugh carried across dancefloors. During a distanced visit to his new Bushwick studio in late February of this year, almost 12 months since either of us had attended a party, De Nieves seemed unusually subdued in French cuffs, his salt-and-pepper hair cut in a bob. He had recently returned from Florida, where his first museum survey, ‘Eternal Return & The Obsidian Heart’, was on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art North Miami. He spoke with hushed awe at seeing the same symbols recur throughout the show, drawn from his lifelong obsessions.

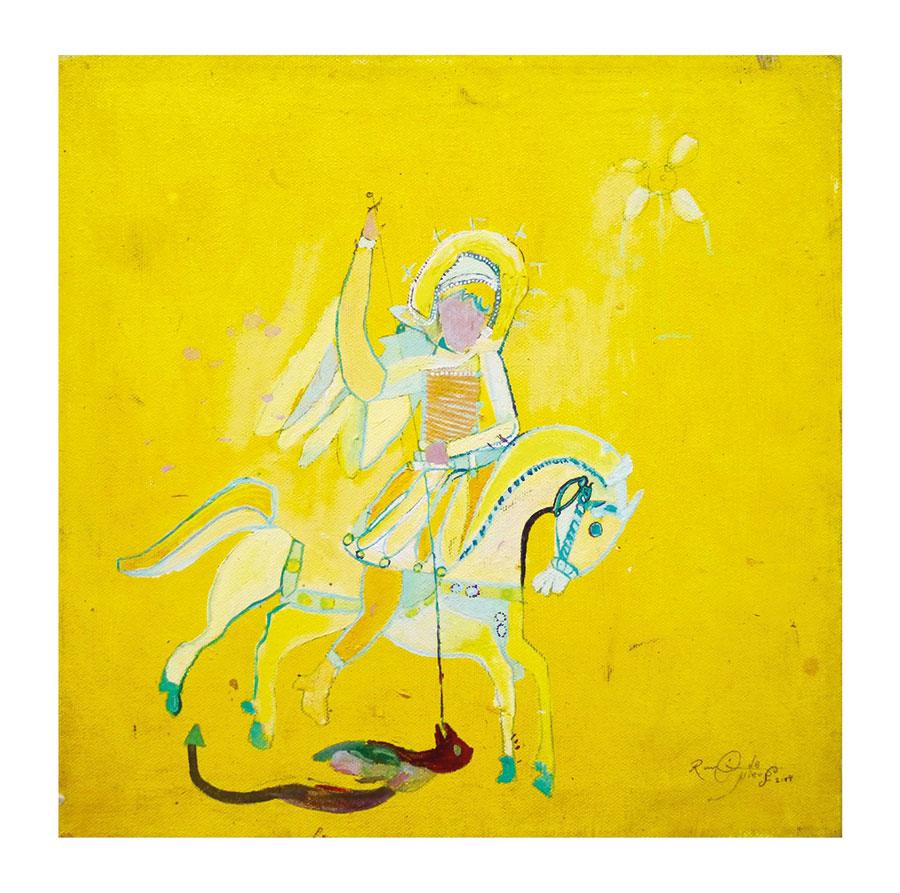

St George and the Dragon, 2003–05, mixed media, 33 × 33 cm

There were the polychrome icons of the cathedral in Morelia, Mexico, where De Nieves was born and raised, which he saw on family church visits after the death of his father when he was two years old. Back then, he would marvel at the pilgrims who crawled for miles to kiss the hand of a statue of Jesus, amazed ‘that an object could hold so much energy and make you feel part of something larger than yourself’. There was the danza de los viejitos, or dance of the old men, in which masked dancers wearing colourful sarape capes and sombreros trailing long ribbons moved in circles in the plaza, representing the constant churn of the elements. There were the mohawks and studded-leather jackets of the straight-edged punks in San Diego, California, where De Nieves’s mother moved the family when he was nine years old. ‘This was another tribe of people trying to represent their culture,’ he tells me of the wild mosh pits at shows by bands like The Locust, whose members donned balaclavas with insect eyes.

When De Nieves was 20, he was accepted to the California College of the Arts (CCA), but opted not to pay the school’s steep tuition fees. Moving to San Francisco’s Mission District – then a working-class Mexican community with a thriving crust-punk scene – he got a job as the live-in manager of an antiques shop called Gypsy Honeymoon. He became notorious for crashing gallery openings in duct-taped stripper heels. ‘There was a period when, every day, Raúl would paint his face and hands red, and dress in a red suit with a red hat,’ the artist Stewart Uoo, who was then a student at CCA, tells me. ‘He was basically doing day drag.’

le champs elysees, 2019, artist’s shoes, fibreglass, beads, glue, costume jewellery, light box, acetate tape, dimensions variable

One day, a woman came into Gypsy Honeymoon with a small embroidery of St George slaying the dragon, which De Nieves bought for himself. In Jacobus de Varagine’s Legenda aurea (The Golden Legend, c.1260), the dragon lives in a pond, poisoning the freshwater source for a nearby city. To appease it, the townspeople sacrifice their children using a lottery system. When the king’s daughter is selected, St George appears by chance and wounds the dragon with his lance. The princess hands him her girdle and, when he lassoes it around the dragon’s neck, the fearsome beast grows docile. Victory comes not with death but with dress-up, when the monster appears too ridiculous to be threatening. This image – and its story – became the subject of a series of paintings, ‘St George and the Dragon’ (2003–05), which De Nieves exhibited in his first show, in the back room of Gypsy Honeymoon, in 2005. St George reminded him of his mother’s courage in bringing him and his siblings to the US for a better life. ‘She’s my ultimate saviour,’ he says.

In 2006, after four years in San Francisco, De Nieves faced another fear: New York, where he moved with no job prospect. It wasn’t long, however, before he landed in a Chelsea gallery show, at Newman Popiashvili, after a curator visiting his apartment studio pointed to his duct-taped heels and declared that he loved ‘that sculpture’. ‘Me too!’ De Nieves remembers saying, though he had considered throwing out the shoes during his move.

Crown Me with Your Iron and Aid Me in My Fight, This and All of My Days, 2020, installation detail

He laughs about the episode now, but it was serendipitous: a shoe, he realized, is a perfect work of art. Its craftsmanship stands metonymically for its wearer as it moulds to the part of the body where one’s weight presses down against the world. Heels can be symbols of female empowerment. They’re sexy; they’re camp. De Nieves bought kitten heels at thrift stores and encrusted them with beads until they could barely stand up on their own. ‘I started to think about architecture, structure, balance, self-expression,’ he says of the sculptures, pointing to one on the floor of his studio, so heavily encrusted that its inner cavity seems turned outward, like the guts of a geode. Over time, the shoes grew legs, torsos, arms, heads – whole bodies of glittering beadwork clad in brocaded costumes that recall, variously, Mexican folkloric dancers, medieval court jesters and 1990s club kids. A breakthrough work was the life-sized figure Day(ves) of Wonder (2007–14), its beaded, go-go platform boots in bright lollipop swirls resembling the hooves of a disco satyr.

In De Nieves’s studio, we circle a number of large figures completed at the start of this year, their iridescent bodies contorted in ways that remind me of the breakdancing buskers on New York subways. The artist coated the beadwork in resin so they could be safely installed outdoors on the High Line for the group exhibition ‘The Musical Brain’, which opened last month. Here, he hopes they’ll reflect sunlight onto the drab skyline of Hudson Yards like anthropomorphic mirror balls. A rearing horse propped up against the wall alongside them – its hide a dense patchwork of plastic emeralds – is bound for the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, where De Nieves will present a solo exhibition of new work this August.

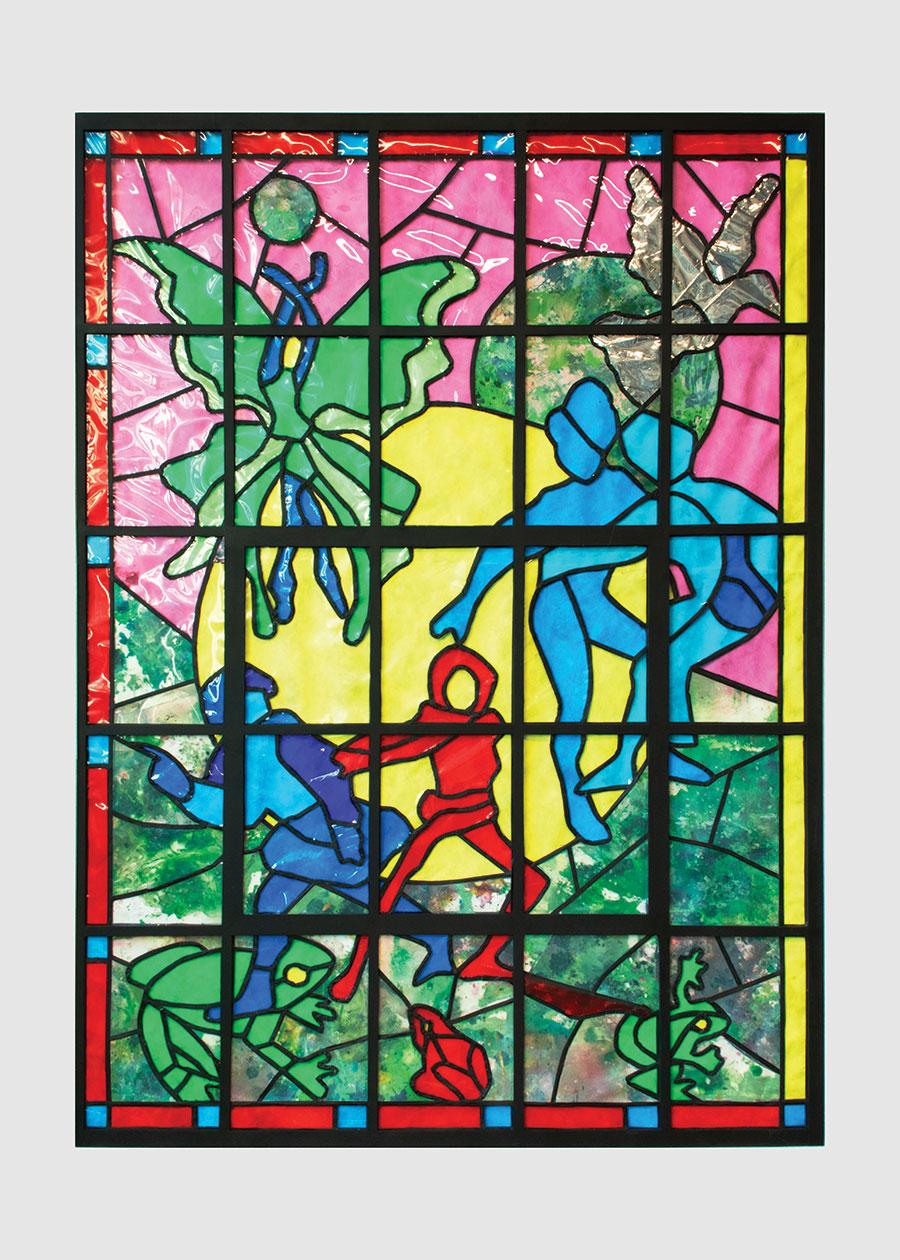

Beginning & the end neither & the otherwise betwixt & between the end is the beginning & the end, 2017, installation view, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Day(ves) of Wonder was De Nieves’s first life-sized sculpture, and its completion in 2014 spurred the return of performance to the centre of his practice. Later that year, he cut up and re-stitched elaborate costumes for The Fool from garments purchased at Mexican street markets. His own personal style also evolved into a pastiche of traditional textiles with the hard edges and glittery finish of Bushwick drag. ‘I treated myself as a sculptural object,’ he says, smoothing his grey hair with beringed fingers.

At the time, De Nieves was living above The Spectrum, an underground venue in a Williamsburg row house that hosted some of the city’s wildest late-night parties. Founded by his friend and roommate, Gage of the Boone, the club was the regular haunt of artists and musicians whose work came to define New York’s queer scene: Arca, Juliana Huxtable, Le1f, Jacolby Satterwhite. I spent my first New Year’s Eve in New York at The Spectrum, half-naked and tequila-drunk, trying to dance in a crowd so dense that I could barely move. I didn’t know as we began the countdown to 2016 that it would be the club’s last party. A week later, The Spectrum closed after its building was sold in a debtors’ court and its tenants were abruptly evicted. Then, on 10 January, De Nieves and Gage curated ‘XPRM/E/N/TAL’ – a day of queer experimental performance at MoMA PS1. For a piece called Somos monstros (We Are Monsters), De Nieves wore a jewel-encrusted bodysuit with a tall conical mask like a papal tiara, and chanted while striking a metal folding chair: ‘I want what’s not mine!’ His noise band, Haribo, followed with a raucous set called ‘DOA at the BOA (Dead on Arrival at the Bank of America)’, featuring ATM machines, inflatable gold bars and a song about overdrawn checking accounts. Making light of being perennially broke, the performance was also a ‘fuck you’ to The Spectrum’s repossessors.

Raúl de Nieves and Colin Self, The Fool, 2014, performance documentation, The Kitchen, New York. Courtesy: the artists, The Kitchen, New York, Company Gallery, New York, and Fitzpatrick Gallery, Los Angeles and Paris; photograph: Paula Court

If The Spectrum introduced me to New York’s queer community, its successor, The Dreamhouse, was the first place in the city where I felt a real sense of belonging. Tucked behind a low, mouldering facade in Queens, the former banquet hall was improbably vast, unfolding room after darkened room in which people huddled to snort lines or have sex. Limbless mannequins were piled in one corner while, in another, vacuum tubing coiled like an abandoned gorgon’s weave. The vinyl checkerboard walls were slick with sweat. At a Dreamhouse party, anyone could appear, anything could happen and one night could easily bleed into the next.

De Nieves set up his studio in the basement. Running the length of the dancefloor, its walls papered with French toile, it was just big enough to accommodate his largest-ever commission: a monumental, pseudo-stained-glass window for the 2017 Whitney Biennial. De Nieves often came there during parties, stencilling coloured plastic gels while the ceiling above him throbbed with bass. Sometimes, friends would come down to smoke cigarettes and watch him work. The finished window, Beginning & the end neither & the otherwise betwixt & between the end is the beginning & the end (2017), was installed on the east end of the Whitney Museum’s fifth floor, transforming the gallery into a gothic cathedral flooded with rainbow light. Figures ballroom dance and fight demons across its translucent surface, amongst baroque architectural facades, decorative urns, doves, flies and crossed keys reminiscent of the Vatican sigil. It’s fitting that De Nieves constructed it in the crypt of a proverbial ‘church’, where queer kids communed in the pre-dawn hours of so many Sundays.

Celebration (LIFE), 2020, installation view, The High Line, New York

The Dreamhouse closed in January 2019, almost a year before COVID-19. Since then, queer spaces across New York have shut because of the pandemic, and it’s unclear if they’ll ever come back. As the sun sets on Bushwick, glinting off the sculpture around us, I ask De Nieves to draw from a tarot deck. He doesn’t pick the Fool, but the Nine of Swords – usually a bad omen. True to form, De Nieves sees a brighter side: ‘Sometimes, things have to fall apart in order to build up and become stronger. Sometimes, you have to get cut in order to heal.’ As he says this, I notice a fly tattooed on the webbing near his right thumb, the same fly that swarms the surface of Beginning & the end. He explains that it signifies the spirit of his father watching over him. ‘It’s also nightlife culture, the desire to infest a space with joyous energy,’ he says, ‘but it’s the easiest thing to swat away. Another vulnerable aspect of human society.’ Like so many of De Nieves’s symbols, the fly can be a source of both good and bad, weakness and strength, depending on how you hold it up to the light. In that moment, I’m transported back to the buzzing hive of The Dreamhouse, with De Nieves cutting his bugs in the basement, and I feel hope for some kind of eternal return. After all, those who have gone are still with us. Each ending is also a beginning.