- Source: MOUSSE

- Author: David Everitt Howe

- Date: February-March 2017

- Format: PRINT

Craft Store Meets Dark, Dark Disco

RAÚL DE NIEVES AND DAVID EVERITT HOWE IN CONVERSATION

Raúl de Nieves’s Ridgewood studio is located in the basement of THE DREAMHOUSE, the reincarnation of Bushwick’s legendary underground club and community space Spectrum—which miraculously ran illegally in a townhome for several years as a decadent, sexualized paean to queer party culture. De Nieves has been a fixture of this extraordinary nightlife/performance art scene for several years as well, both as a front man in the bands HARIBO and Somos Monstros, and in his own capacity as a performer and fantastically dressed man-about-town.

Rejoice, 2016. Courtesy: Company Gallery, New York.Photo: Kyle Knodell

Raúl de Nieves and Doron Sadja, performance at ISSUE Project Room, New York, 2017. Courtesy: the artist and Company Gallery, New York. Photo: Cameron Kelly Media

Nightlife provides the literal bones for his work; many of de Nieves’s sculptures began as outrageously chunky high heels, inspired by the kind he ’d wear out to parties. From there, they’d grow up, literally from their feet, into garments and objects—“disco” agglomerations of beads and thread, sequins and hot glue—forming characters featured in folkloric, epic narratives revolving around life and death, beginnings and ends, and the journeys made in between.

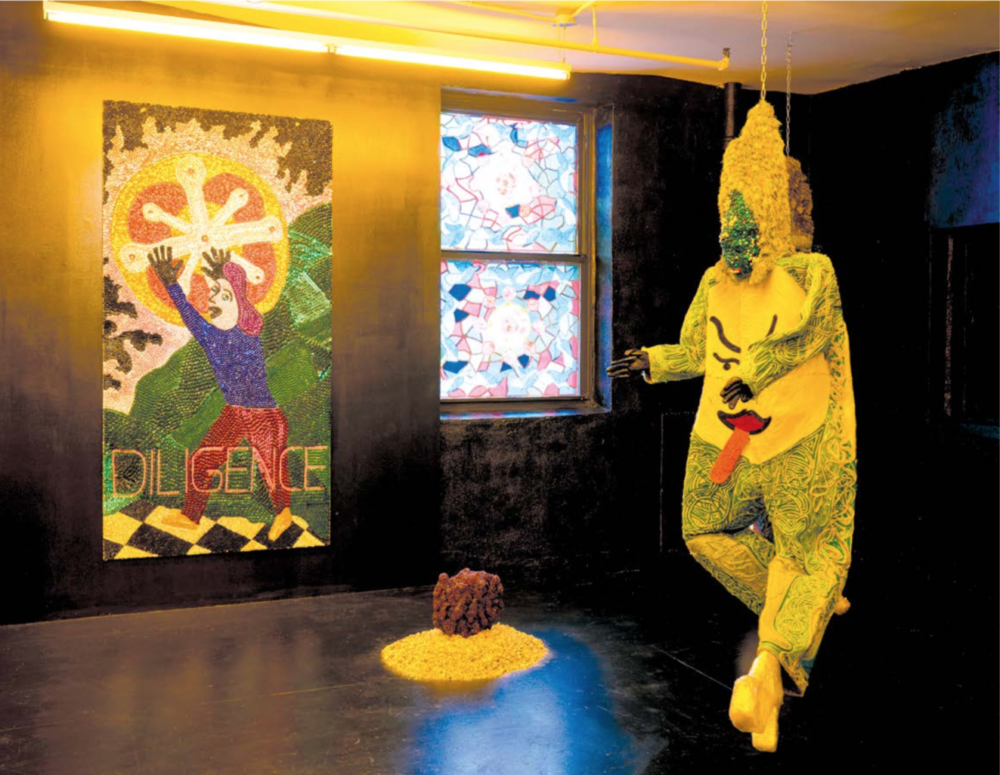

In his studio, these impossibly intricate, fantastical, and lifesize people—which resemble a queer, camp version of Nick Cave ’s costumes—stood next to hyper-colorful, stalactite-like sculptures and an in-process mural. All are destined for the 2017 Whitney Biennial. There was a woman made of densely coiled white threads, her face a burst of fire-red sequins surrounded by boughs of dried brown grass and a red cross, holding an apple as if she were Eve, The longer I slip into a crack the shorter my nose becomes (2016). An accompanying male figure—Man’s best friend (2016)—also in white, featured the same red sections, this time surrounded by a kind of furry material. And there was Somos Monstros 2 (2016), an incredibly intricate “man” (the genders of these are somewhat ambiguous) made of vintage military trim, plastic beads, and costume jewelry. These were joined by de Nieves’s “stalactites,” which look like they’re cut from the same cloth as Jeffrey Gibson’s Native American craft sculptures, except more freeform and unwieldy.

We sat down and chatted over coffee, and I touched all the work while I still could.

DAVID EVERITT HOWE These costumes came from your show El Rio at Company, no?

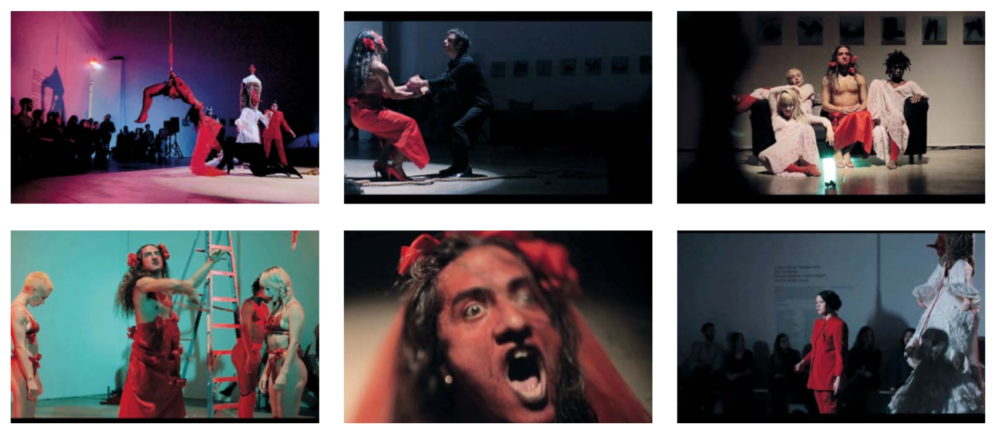

RAÚL DE NIEVES These are new. I made them because I was in a show at the ICA Philadelphia in November, called Endless Shout, which was performance-based—Micki Pellerano, Monica Mirabile, and I came up with the performance The Way and the Body (2016), and made these costumes for it. I also performed as Somos Monstros—we ’re essentially a noise band that plays metal instruments, like actual metal. But yeah, we try to perform “incognito,” wearing these.

DEH So you can wear The longer I slip into a crack the shorter my nose becomes?

RDN Yeah, you can.

DEH [peering at the sculpture up close] How are these threads attached?

RDN It’s all glued. It ’s just easier. I’ve sewn stuff before, but it just doesn’t have the same quality; I can’t clump as much of it, you know? And it becomes more like this automatic, repetitive task. I pressed the yarn down onto the garments, so it ’s like each individual string was from a spool of yarn, and now they’ve become these creatures. This figure is supposed to symbolize the giver, and she ’s presenting you with life. The whole thing is about the circle, the beginning and end, the experience of life. And Man’s best friend is her companion. He’s too tall for this room so their heads have been switched, but he signifies the dog. [he’s connected to his female companion with a leash]

DEH Are these “tales” taken from actual mythology? Or are they your own?

RDN I definitely work with stories that I’ve learned, but I try to fit them into my own narrative. I think that’s the importance of the storyteller: you can shift anything to fit your own vocabulary. It’s really fun to work in this manner, because [the works] have this sculptural element, but then obviously—

DEH Sorry, I’m touching it—

RDN No, you can touch it. But then the sculptures are actually activated. Like all my work, these were made from shoes, and now they’ve turned into these—

DEH From your shoes!?

RDN Yeah, they were a shoe at one point.

DEH A high heel?

RDN Yeah, and so obviously it’s not a shoe—well, it ’s still a shoe for someone.

DEH People always associate your work with Nick Cave, which makes sense, but the point of Nick Cave ’s work is to cover up identity—race, gender, sexuality—whereas this stuff is so gay [laughter], or queer, rather. It shows a very specific kind of identity, in a way.

RDN It ’s funny. People say, “Your work reminds me so much of Nick Cave,” and I find that interesting, because we have very different backgrounds. The self-adornment thing is something I saw as a child, you know, these characters on the street, costumed. I’m from Mexico, and on Sundays at the square there would be these old men dressed up, doing ritualistic dances. It’s tradition. I think that’s why I work so much with this adornment of the self, and also channeling other beings through costuming, with forms of presenting ourselves. I love dressing up, I like to create my own self.

DEH For going out?

RDN Yeah.

DEH Do you still do that?

RDN Yeah.

DEH Cool. Like—upstairs? [laughter]

RDN Yes, upstairs. How convenient. I’m all, “Time to go out!” Then I’m suddenly at the party.

DEH I’m always whining, “Ugh, I don’t want to go to Bushwick.” From Red Hook it takes an hour and a half to get there.

RDN Yeah, that ’s fucked up.

DEH I did it to myself. [looking at the sculptures again] These are amazing. It’s like Nick Cave, but craft-store Nick Cave.

RDN All these beads are what kids use to make friendship bracelets. I love the material, because it takes time. And time is the most important aspect of this. The material becomes secondary.

DEH How do you mean?

RDN You would usually never think to buy fifty bags of beads and glue them all together. When I started making sculpture I chose beads, because I wanted to think of accumulation and mass and weight and balance, and I think that’s why I also focused on something that was so personal to me, which were my shoes.

DEH [looking at UUU, MEE (2015-2016), a beaded high heel of black-and-white stripes] Wow, this is fucking amazing.

RDN It ’s really cool, right? This is where I started exaggerating these forms.

DEH It ’s so drag queen.

RDN But it ’s my shoe.

DEH It reminds me of Leigh Bowery, and his graphic, crazily proportioned costumes.

Celebration, 2016, El Rio installation view at Company Gallery, New York, 2016. Courtesy: Company Gallery, New York. Photo: Kyle Knodell

Raúl de Nieves and Doron Sadja, performance at ISSUE Project Room, New York, 2017. Courtesy: the artist and Company Gallery, New York. Photo: Cameron Kelly Medi

The Way and the Body (stills), 2016. Starring Raúl de Nieves, Micki Pellerano, Monica Mirabile, Sigrid Lauren, Tara-Jo Tashma, Kathleen Dycaico. Produced by the Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania. Courtesy: the artist and Company Gallery, New York

Raúl de Nieves (Morelia, Mexico, 1983) is an artist, performer, and musician based in Brooklyn. His work en-compasses narrative painting, decadent multimedia performance (often with his band Haribo), large-scale fi-gurative sculpture, live music, ornamentally crafted shoes, and garments. De Nieves has exhibited widely, including at Mendes Wood DM, São Paulo; the Museum of Arts and Design, New York; Rod Bianco, Oslo; Shoot the Lobster, New York; and elsewhere. He has performed in and around New York at Artists Space, BOFFO, The Kitchen, Performa 13, and Real Fine Arts, and at other venues in other places. In 2015, he was included in Greater New York at MoMA PS1.

David Everitt Howe is a Brooklyn-based critic and curator. He received his BFA from the Savannah College of Art and Design and his MA from Columbia University. He has recently mounted major solo exhibitions and performances by Charles Harlan at Pioneer Works, Dynasty Handbag at The Kitchen, and Emily Roysdon at Participant Inc, while his writing has recently appeared in BOMB, Frieze, Mousse, and Art Review, where he’s a contributing editor. Currently, he’s Curator/Editor at Pioneer Works and Online Art Editor at BOMB.

El Rio installation view at Company Gallery, New York, 2016. Courtesy: Company Gallery, New York. Photo: Kyle Knodell

RDN I saw this video of him performing on stage, and he’s wearing a dress and singing “fuck you”—I’m dying—and he puts himself on a table and starts waving his legs. And then all of a sudden a human being pops out of him; he had on this crazy costume where it looked like he’s just a fat person, and then this girl literally bursts out of him like she’s covered in blood, and it’s the nastiest thing ever. And then he feeds her pee.

DEH Amazing. I see him in your use of colors and the super-graphic shapes and crazy heels. And the weird headgear.

RDN And the weird headgear. I love headgear. I mean, this fucking sheet is like the coolest headgear ever [pointing to a costumed mannequin in the corner, with a sheet draped over its head].

DEH I would wear that. To work.

RDN I was playing with this idea of the shoe, and almost creating a memento of it, because shoes speak to me in so many different ways. I think that was the challenge: to keep the form alive but also abstract it so it becomes more a creature of itself.

DEH These “stalactite” works are very different than the others.

RDN For sure. My work is very faceted. I started out as a painter, and now I think of these costumes as wearable paintings. You can actually crawl into them and shift them. When I was drawing and painting, I felt like the works were so hard to live or experience. But these costumes allow the character—the work—to come alive, like in reality. That’s why I think the figure is always so important to me, because it allows anyone to walk in and form their own ideas about what it’s about.

DEH Especially with an exhibition it’s much more open-ended, whereas in a production like The Fool, at the Kitchen, it ’s going to be much more led by you and Colin Self.

RDN There it tells the journey of the self. We start out the show by doing this tongue-twister title, to see all the stages of the beginning and middle and end, and you can’t forget that without the beginning there is no end, but the end and the beginning—how do you get into those, you know? My practice is multifaceted; I’m trying to find all those stations that I can somehow weave together to create a story.

DEH The works manifest differently, too.

RDN They do. That’s why they have this fantastical aspect; I want to tie myself to traditional ideas of understanding life. I gave up the idea of being formally religious. I was raised Catholic, and it ’s so strict: “This is how it is, and it’s bad otherwise.” I want to think more about the bad side. I want to feel guilty.

SIRI I didn’t quite get that. Hey, Raúl.

RDN In The Fool we’re dealing with the self being afraid of the self, and confronting that fear and what that means.

SIRI I didn’t quite get that.

DEH Shut up, Siri!

RDN She’s, like, literally on drugs. For the Whitney I’m making this giant mural that’s going to be about forty feet, in this stained-glass format. The fly is one of the main characters in it; the fly symbolizes humility. We are like flies, yet we’re disgusted by their presence. They’re these things that cultivate from nothing and reproduce like crazy. And they eat shit; they eat your dog’s shit and your shit. At my old studio we had a mulberry tree, and in the summer it was so amazing, because all these mulberries would fall onto the floor.

DEH What is a mulberry? Is it a fruit?

RDN It ’s a fruit—dark, like a blueberry.

DEH And you can eat it?

RDN You can eat it, and they’re usually wild, and in the summer these mulberries would rot on the floor and become a cesspool of flies.

DEH Gross!

RDN It was so disgusting, so I hated flies. My friend would always think of the fly as the devil. One day I was like, “These fucking flies, get them the fuck out of here!” I was going crazy. Then I look over and, ohhhhh, my god, they’re fucking.

DEH That’s so gross. But how did you even know they were fucking?

RDN They were literally on top of each other, having sex. I was staring at them.

DEH You’re crazy.

RDN And now they’re all over my work. I really appreciate that, this idea of confronting your fears. You know you’re afraid of it, then once you realize there’s nothing to be afraid of—the only thing you can be afraid of is yourself—you’re the only one who can actually create damage, you know?

DEH And create your own fears.

RDN That’s the one thing I’ve learned through this practice: that it’s giving me so many ways to understand why we’re here. These lessons we’re supposed to experience, the fear, has always been something I’ve been trying to understand. Why am I afraid of things? Am I afraid of death? What will I do when my mom dies? I ask myself all these questions.

Day(Ves) of Wonder, 2007-2014. Courtesy: the artist and Company Gallery, New York