- Source: ARTSY

- Author: Charlotte Jansen

- Date: JUNE 26, 2023

- Format: DIGITAL

Contemporary Artists Are Reviving Vanitas, Reflecting on Death and Decadence

Cecily Brown, Aujourd’hui Rose, 2005. © Cecily Brown. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Cecily Brown, All Is Vanity (after Gilbert), 2006. © Cecily Brown. Courtesy Two Palms, New York.

Oysters, lobsters, Louboutins—and death. At Cecily Brown’s current exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum Museum of Art, “Death and the Maid” (through December 3rd), the trappings of capitalist society seem to slip into oblivion under her lively, vigorous brushwork and lucid tableaus. Skulls, mirrors, and references to paintings of the past remind us of the madness of materialism and the certainty of death, recasting the classic theme of vanitas for the contemporary age.

Historically, the aim of a vanitas painting was to point out the vain pursuits of our mortal existence. Evolving out of a distaste for decadence and wealth, fueled by Calvinist attitudes in 16th-century Europe, these paintings imparted a clear moral message. The burgeoning middle classes had suddenly been able to afford jewels, quills, luxurious fabrics, sheet music, and books. But, these paintings warned, no matter how much pleasure those material possessions may bring, all is futile in the face of death. In these still-life compositions, the transience of life was commonly represented in depictions of skulls, burning candles, flowers, and soap bubbles.

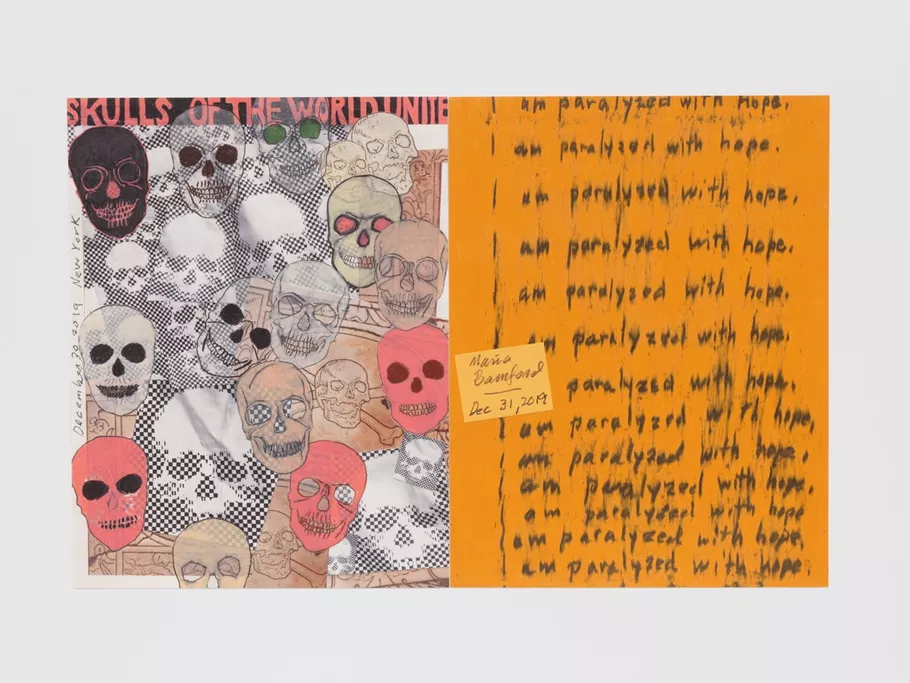

Roni Horn, Skulls of the World Unite • Orange Hope, 2022. Photo by Tom Powel Imaging. © Roni Horn. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Unlike memento mori—another genre of painting designed to remind the viewer of their mortality—vanitas works can be distinguished for their inclusion of displays of luxury and collections of items alluding to pleasure. It’s perhaps no surprise that vanitas is making its way into the works of contemporary artists—especially in bodies of work produced during the pandemic that are now being seen in public for the first time.

Roni Horn’s current solo exhibition, “An Elusive Red Figure…” at Hauser & Wirth in Zürich (through September 16th), presents outtakes from “LOG,” a body of work produced as part of a daily drawing practice she began during lockdown. Many of these humorous, diaristic works, such as photographs, notes, drawings, and collages, take delight in juxtapositions that reveal the absurdity of our attachment to things, and the transient nature of being. “Snowflakes are in season now” reads one observation, under a reproduced photograph of a snowflake. “But this is the only one around.” Found images of skulls taken from different sources (an old church; a Comme des Garçons jacket) appear in several works; others refer to disappearing, dying, and obliteration.

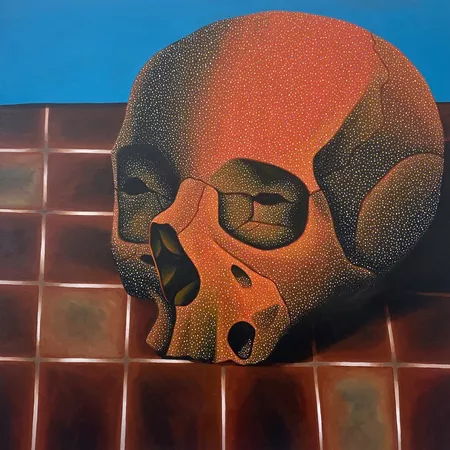

Janice McNab, Skull, 2020, Galeria Fermay

Janice McNab, Slits, 2020, Galeria Fermay

In the works of emerging artists, too, vanitas continues to evolve. Scottish artist Janice McNab’s photorealistic paintings Slits and Skull (both 2020) were painted “as a cri de coeur in the middle of the pandemic,” she said in an interview with Artsy. As even basic essential consumer goods became luxuries, the motif of the skull gained a new immediacy for McNab. Describing the two works as a “self-portrait,” she said, “I painted both parts as death and the psychic geography of our homes looped through each other in silent repetitions of eating, sex, and loss.” The skull is the image of death—but McNab modeled it out of ice cream. The real death, in fact, appears in Slits, a painted corpse of a Scottish salmon. “This is where the violence is,” she said. “In choosing it, I was trying to layer the privacy of immediate effects with a reflection on the wider eco-systemic body the pandemic also made us all increasingly aware of.”

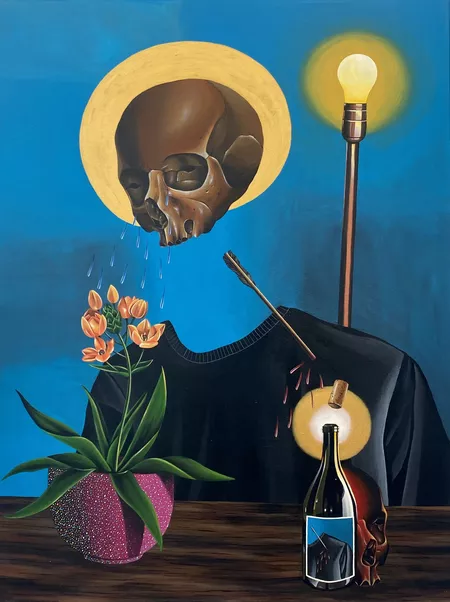

McNab is not the only contemporary artist returning to the vanitas tradition. “I have always been attracted to vanitas,” said Jaylen Pigford, an Afro-Latino painter based in Houston, Texas. “For me, I view the world as being very balanced.…Life and death, good and bad, light and dark.” In saturated gradients and quasi-mystical compositions, Pigford reimagines symbols commonly found in classical vanitas paintings, such as skulls and flowers, and introduces loteria cards and arrows “as symbols of life, death, love, pain, and sometimes just for the nostalgia,” he said. He noted that they can “help bring the viewer to a time or place in their lives when a certain object that I paint was common.”

Pigford has returned to the skull continually since 2016. Inspired by the traditions of the Dia de Los Muertos, the artist transferred the skull to canvas “as a way to bring my family members back to life, in a way, through my paintings.” Pigford does not see the skull as a necessarily morbid symbol, but rather as a reminder of our shared humanity. “A skull allows the opportunity for the viewer to place themselves in the painting,” he said. “The skull is a common feature we all share, which should tell us at the end of the day we are all the same.”

Jaylen Pigford, Dotted Skull II, 2023, Ivester Contemporary

Jaylen Pigford, The Growth, 2023, Ivester Contemporary

For Becky Kolsrud, an American figurative painter known for her parabolic depictions of women with flat planes and scintillating blues, vanitas is a recent theme: “The first time I included an image of a skull in a large painting was in early 2020. I was living in a historic house where George Hodel, the alleged Black Dahlia murderer, lived as a child when his parents built it in 1921. I was excited by the confluence of themes that touched George Hodel’s life, including Los Angeles history, film noir, Surrealist artists including Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp, and true crime, of course.”

That reference made its way into the triptych As Above, So Below (2021), which evokes a strange and symbolic narrative: In a lake, a woman holds a ghostly man’s head, in a romantic tryst; a skull sits in the foreground, while disembodied feet seem to dance on the water, as fire blazes in the background and a body, semi-nude, sprawls on a verdant hillside.

Becky Kolsrud, As Above, So Below, 2020. Photo by Jeff McLane. Courtesy of the artist and JTT, New York

In a suite of recent works presented at the artist’s solo exhibition “Ghosts of the Boulevard” at Morán Morán’s Mexico City gallery earlier this year, motifs of the moon, skulls, and disembodied figures appeared throughout. These symbols have taken on a very personal meaning for the artist and her own confrontations with grief and loss.

“The skull felt like an alternate self, and a way to address my fear of death,” Kolsrud said, reflecting on the illness and subsequent death of a friend. “I saw [her body] transform as she was dying.…I started to paint skeletons in the bath, thinking of her. I like that a skull is the most generic face. It’s the shared, timeless face.” For her, there is no moral compass in the painting, but it is a space to contemplate what it means to be here, now.

Becky Kolsrud, installation view of “Ghosts of the Boulevard” at Morán Morán, 2023. Courtesy of Morán Morán.

In a consumerist society that for the most part ignores mortality, vanitas provides contemporary artists a way to describe the perplexing nature of our times, where the only chance at immortality might be the creative act itself.