- Source: ARTFORUM

- Author: EDITORS

- Date: JUNE 01, 2019

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

CONFESSIONS ON THE DANCE FLOOR

Reveries From The Gay Bar

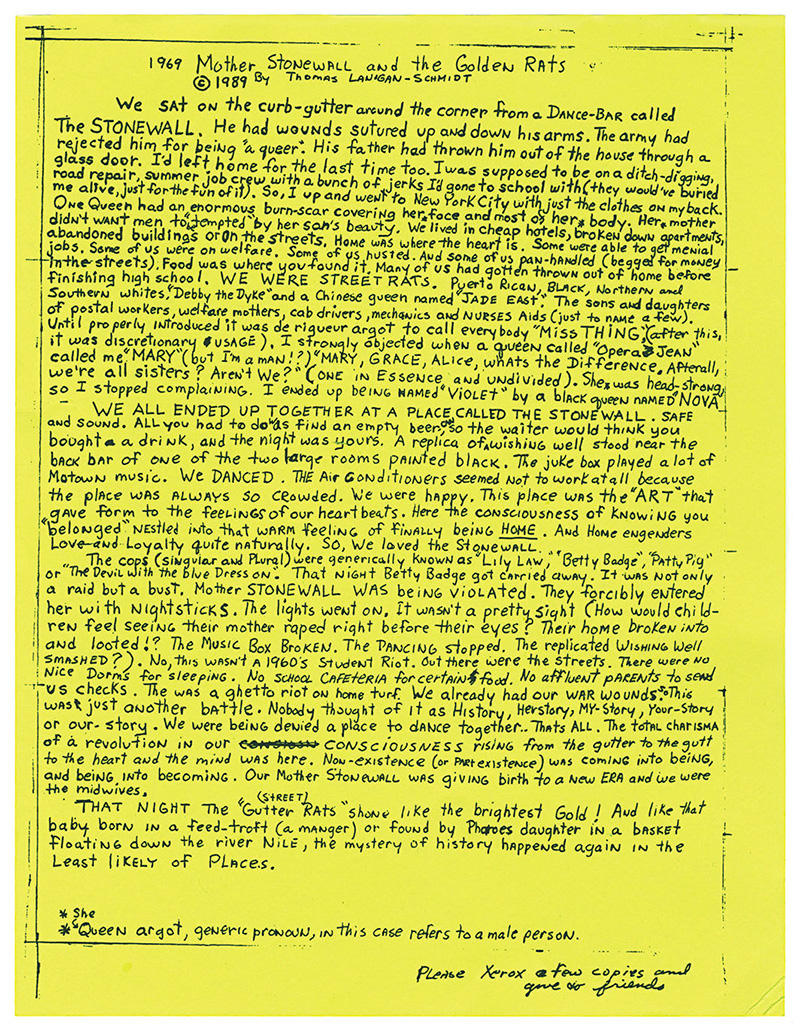

Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt, Mother Stonewall and the Golden Rats, 1989, Xerox, 11 × 8 1⁄2".

“WE ALL ENDED UP TOGETHER AT A PLACE CALLED THE STONEWALL.” June marks the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall uprisings. To celebrate the occasion, Artforum invited some of our favorite artists and writers to share an early or particularly vivid memory of a gay bar. Our only proviso: Keep it quick and dirty. Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt’s classic 1989 broadside “Mother Stonewall and the Golden Rats” kicks off the package. Our twenty-four gorgeous respondents offer not an exhaustive view but a festival of testimonies to Mother’s surplus grit and glamour.

Stonewall Inn, Christopher Street, New York, 1969.Photo: Diana Davies.

MX JUSTIN VIVIAN BOND

Back when I was growing up, the legal age for entering a bar was eighteen. So on my eighteenth birthday, my best girlfriend and I got extremely drunk and made our way to our small-town gay bar, the Bull Ring, in Hagerstown, Maryland. Her older cousin was gay, and he’d told me that the most elegant woman he’d ever seen was in fact a man he saw at the Bull Ring. He described her as being dressed like a 1940s movie star. I had to see this woman. We looked everywhere. Sadly, I never saw her—but I’m pretty sure I eventually became her. Regardless, I had sex with my friend’s cousin, who gave me my first and only Quaalude before entering me on the floor next to his washing machine. So let’s consider that whole night a win!!!

Mx Justin Vivian Bond is a House Witch, a Cabaret Enchanteuse, a Voluptuary, and a BadAss! Glamour is Resistance

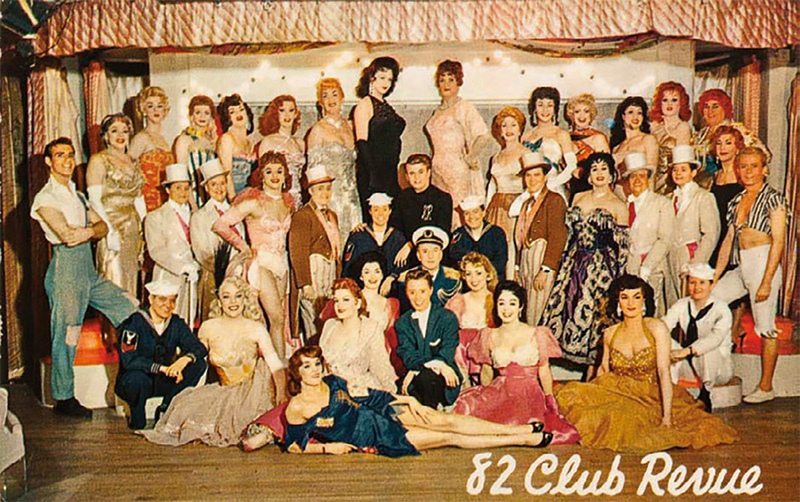

82 Club postcard, late 1950s.

JUDITH BUTLER

I am not sure about my earliest memory of the gay bar, but I do know that I was in bars very often starting at the age of eighteen, or just before. They seemed to be spaces of freedom and excitement, islands in an otherwise unfriendly world. In New Haven, in the late 1970s and early ’80s, the bar Partners was known for its upstairs-downstairs configuration. Men were upstairs, and drag shows became regular events, a kind of pre-Provincetown testing ground for the up-and-coming.

Oddly, the same structure characterized the gay bar I went to outside of Albany in the mid-’70s. In Albany, however, the different strata reflected different vibes: There was dancing to disco on one floor, slow cruising on another, and I was, well, not so very sure about what was happening in the recesses of the building. The whole place was warm, if not hot.

By the time I started going to bars in NYC in the late ’70s, there was the feel of a celebration and a political movement. We spilled into the street: For brief moments, we seemed to own the neighborhoods. If you wanted a bar for women only, you had a few options, but one of them, Sahara, was expensive and I felt awkward in my sweatshirt. Another, on West Fourth Street, was great, but today it seems to be a looming bank. Over the years, so many people and communities, so many real and potential pleasures, were driven out of those neighborhoods, the ecstasy replaced by dispossession. HIV shot mourning and politics into the scene, and for most of us, divisions between women and men seemed to break down. The public refusal to acknowledge HIV’s seriousness, the state refusal to fund its research, gave rise to rageful and pointed action. And the realization that alcohol and drugs destroyed some people’s lives and relations gave way to a broader reflection on how communities can and must sustain each other.

As categories of gender opened up, the sense of community became ever more complex and the tasks of solidarity more challenging. But somewhere in the course of all these changes there was a sense that desires were to be lived and honored in a network of supports. There’s still a gay bar around where I currently live: the East Bay. It has a retro feel, and maybe even cultivates that as a market niche. It would not be where I now go to find community, but I certainly once did. The gay bar changed my ideas of movement, dance, collaborative ecstasy, connection with those I did not know, anonymous solidarity, all of it happening in an aura of a generalized permission to live, to breathe, to desire, to find “your people” for a time.

Judith Butler is Maxine Elliot Professor of Comparative Literature at the University of California, Berkeley.

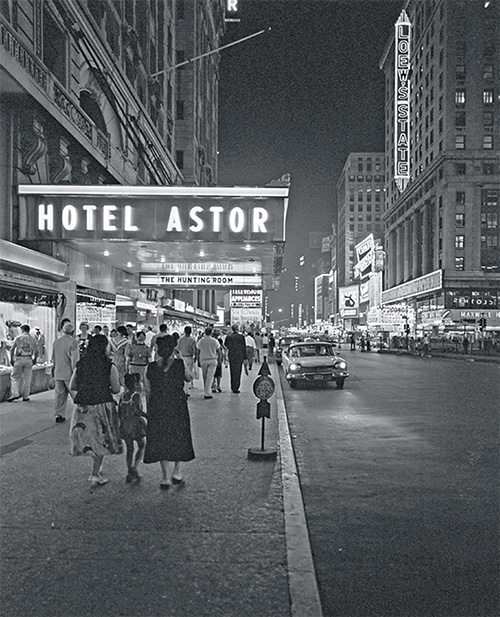

Hotel Astor, Times Square, New York, 1958. Photo: Marty Lederhandler/AP/Shutterstock.

SUR RODNEY (SUR)

As a tall, muscular gymnast not yet of legal age in 1971, I started exploring Montreal gay bars. I found most to be dark, dingy holes with a small stage for drag shows. Not really my interest. A year later, on a US West Coast adventure, I discovered something different. The traffic moving in and out of one bar piqued my interest. I walked into a lobby that had a bulletin board I read with amazement. So many men being open about what kind of hookup they were looking for. I’d discovered a leather bar. When I entered the main bar, the interest I was attracting was noticeable. Maybe riding commando under my tight, hip-hugging white jeans and T-shirt meant something to these guys. That’s when I discovered I was desirable.

Sur Rodney (Sur) is a writer, artist, and archivist based in New York and London.

Rage, West Hollywood, CA, ca. 2000. Photo: Amanda C. Edwards/Shutterstock.

ALEXANDRO SEGADE

I remember not being able to go into the bars in Hillcrest, the gay neighborhood of San Diego, near where I went to high school. And then I moved to LA for college and was still not old enough to go to the bars on Santa Monica unless it was an all-ages night, but that was OK, I looked young for my age and maybe even was; it was the early 1990s. Madonna’s Truth or Dare and Calvin Klein underwear: An aesthetic, a particular brand of gay sensibility had been implanted into the imaginations of us UCLA freshmen gay boys, and with it a vision of a gay club was conjured, promising to be the place to play out that fantasy or try on that identity or act out that acting challenge. And so I remember taking a bus from Westwood into West Hollywood with Malik and Jamie and Sonny on all-ages night, searching for this elusive thing that, now that I look back at it, we already had but thought we might find at Micky’s or Rage or Trunks (no, we knew it wasn’t at Trunks, tbh) or the Probe, where you could really dance—they all blur together in a loud, warm-weather rainbow night of freedom rings and tanks and red Gap jeans (was that just me?) and Caesar cuts and lines to get in and wristbands. Older men looking at us and none of us knowing what to do about that, we weren’t drinking, just standing in circles dancing together sober, looking over our shoulders for someone else to vogue with or talk about voguing with, but ending up together at the end of the night, lying on the carpeted floor of the apartment and contemplating safe sex while listening to CDs.

Alexandro Segade is an artist based in New York.

CYRUS DUNHAM

One summer in high school I studied abroad in a small town in Italy and was totally obsessed with this British girl who was there living with her aunt. I knew I was gay or whatever, but I definitely wasn’t going to tell anyone. The girl started fucking an Albanian guy and I left, heartbroken. I went to Rome to spend a week with my mom’s friend. He could tell I was sad. The second or third night I was there he put me on the back of his friend’s motorino and took me with a big group of guys to a gay discotheque in the outskirts of the city. He and his friends let me get drunk, took me around and pointed out which go-go dancers were infamous for sleeping with Catholic bishops and priests. One especially hot dancer was apparently the pope’s boyfriend. That really cheered me up. I found my adolescent girlhood so unbearably boring. If these people were fucking the pope and dancing on tables, then maybe there was hope for me to have fun someday.

Cyrus Dunham is a writer based in Los Angeles. Their book A Year Without a Name will be published in October by Little, Brown and Company.

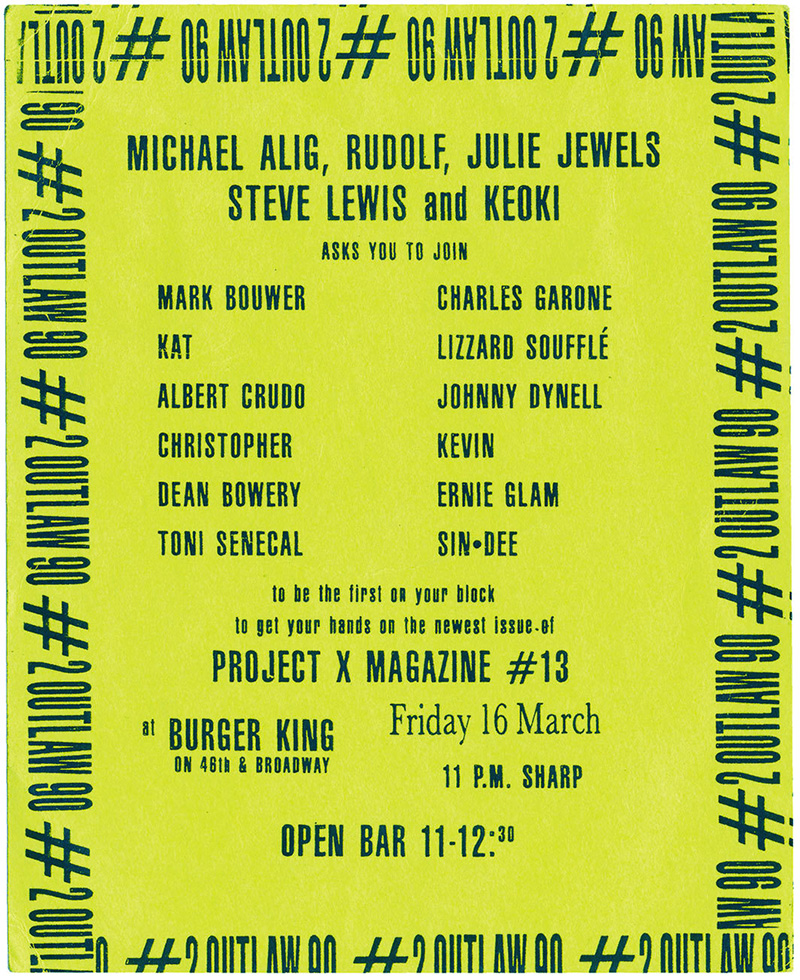

Project X, flyer for an “Outlaw Party” at Burger King, 1990.

BJARNE MELGAARD

I truly believe that nightlife can be a radical way to transcend into queer identity. For me, that path began in Oslo in the 1980s when aids was killing thousands and nobody did anything. At first the disease seemed far away, in the USA, but soon HIV-infected men began to appear and talk about a gay plague in Norwegian media, and we all went and got tested every time we gave somebody a blow job.

I was eighteen and identified as an anarchist. I had long purple hair and heavy eye makeup and wore communist T-shirts with oversize suits. I was convinced that the only option was revolution, with the extreme left taking over Oslo. Problem was, at that time, the young Oslo anarchists hated gays, so I never got to do much except argue about the fact that queer identity was crucial to any revolution—something I still believe.

One night, one of my comrades said, “You wanna check out Metropol?” I never looked back.

Metropol was the first gay nightclub in Norway that absolutely everybody went to—every weekend, even in the middle of the week. I met my first fuck there—a punk kid with blond and green spiked hair who, despite his look, was into the Pet Shop Boys.

After I dyed my (very long) hair purple for ages, it got so damaged that I had to cut it all off. I adopted a short haircut and a mix of jeans and Junior Gaultier and went as much as possible to Metropol, a place where you could be queer and believe in the revolution. It was my second home. It was also a home for the trans community that was harassed every day, everywhere, and we all had fun just screaming “fuck you!” together at the healthy Norwegians who hated us.

Now I’ve been to basically every gay bar in Europe, and I haven’t experienced anything else like Metropol’s warm, cool, anything-goes atmosphere. Old mixing with young, punk with bourgeois, immigrants with Norwegian queens, disco with Eurotrash hits. In those disturbed times, amid an epidemic, it was all about inclusion and the will to fight and take care of the sick.

And it was a time when nothing was digital, so if you wanted to fuck or meet somebody to fall in love with, you had to go out.

Bjarne Melgaard is an artist based in Oslo.

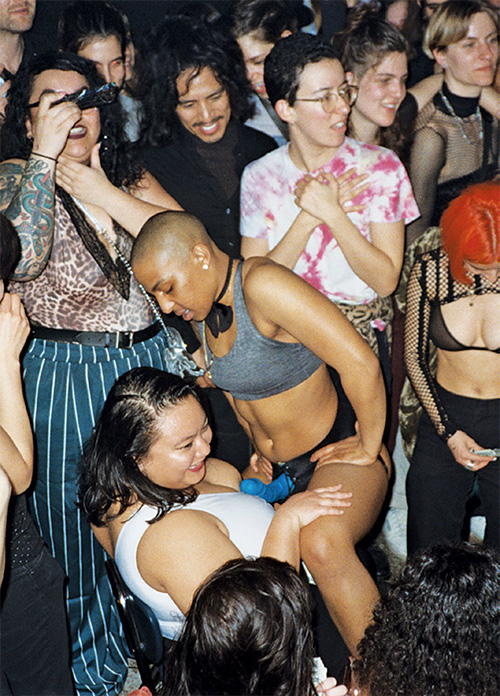

GUSH party, H0L0, Brooklyn, New York, March 22, 2019.Photo: Peyton Dix.

ANGAL FIELD

Mid-gender-transition, I avoided nightlife, uncertain about my new body and how to move it. At GUSH, an intersectional, lesbian-leaning party in New York City, performers gave lap dances with strap-ons, and I found revelatory haptic possibilities and dance moves in a crowd that shared desire.

Angal Field is a writer, photographer, and director based in new york.

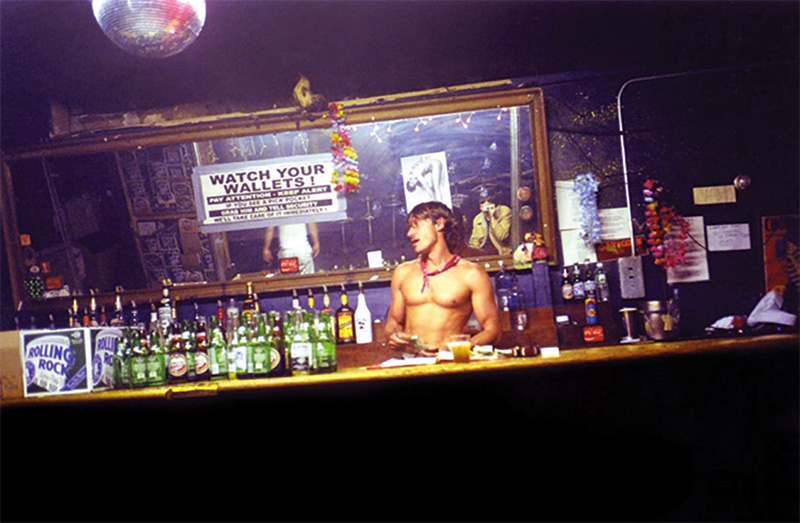

Ryan McGinley, The Cock, 2000.

EVERY OCEAN HUGHES

That time JD Samson and I were in a lesbian bar and the whole room asked us if we were in costume. We were not. And that time I sat down next to Queen Latifah and smoked her smoke. And at the Cock on Avenue A in New York you’d get a free drink if you were topless for the “Thong Song,” that’s the picture. I still know a lot of the people on the floor from those nights.

Every Ocean Hughes is an artist and writer.

SAM MCKINNISS

You want my most vivid memory? Not likely. I’m kind of an alcoholic. But I do remember turning twenty-eight at Metropolitan in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. I got the crowd there on the patio out back to sing “Happy Birthday” to me seven or eight times over the course of a long evening. Complete strangers as well as everyone I knew. It was obnoxious but that’s what I wanted. The magic of gay bars is the permission to do whatever you want, and they have booze there. When my little sister turned twenty-one she asked me to take her out for her first legal drink. So I took her to the Polo Club in Hartford, Connecticut, now closed, where the drag queens would pull hot guys onstage, rip their pants off, and then everyone would applaud their naked genitalia. Oh we had fun.

Sam McKinniss is an artist based in New York.

DOUGLAS CRIMP

I touched on this memory in my book Before Pictures (2016): In my early college years in New Orleans, around 1963–64, my first gay-bar experiences weren’t in fact in gay bars but rather in a Greek sailors’ bar where men danced traditional dances with each other. When I think back on it now, it’s not the sailors I remember particularly; it’s a couple of dockworker regulars, butch queens, not in full drag but wearing full-face makeup and carefully coiffed DAs. I wish I’d been gutsy enough to pursue them.

Douglas Crimp is Fanny Knapp Allen Professor of Art History at the University of Rochester.

CARLOS MOTTA

Going to Las calles de San Francisco, a 1990s gay bar in Bogotá, was like descending into the underworld of necro-eroticism. One night at showtime (around 1 AM), the club went dark and five long boxes were wheeled onto the stage. Suddenly, Corona’s “Rhythm of the Night” began blasting from the speakers and a dim red light was cast on the boxes, which slowly opened: They were coffins! Inside lay very hot and well-endowed dancers—fully erect. The audience didn’t shy away from engaging the “dead”: Folks touched them, sucked them, and jerked them off. Eventually they rose from their graves to perform go-go routines. While gay life in Bogotá for a seventeen-year-old wasn’t all that easy, Las calles de San Francisco made sure it wasn’t boring!

Carlos Motta is an artist based in New York.

YOUSSEF NABIL

It was November 1991 in Cairo. It was my birthday and I was just turning nineteen. My best friend from school, Karim, took me to a bar for a drink with his friends. The bar was in an old Oriental Palace Hotel in the chic neighborhood of Zamalek. It was exactly as you would imagine: a palace ballroom with a piano player, dim light, lots of cigarette smoke. All the customers were men—the only women you could see were the servers, who were all Egyptians and very at ease talking and laughing while bringing drinks to the boys. It was a mix of foreigners and locals, every social class and every age, all together. It was beautiful to see that scene in Egypt. People were happy to have finally found a place to meet. It definitely opened my mind to a whole new world that I hadn’t known could exist. The bar is now closed but every time I pass the hotel, I remember my first time there with Karim, who sadly died of AIDS a few years later.

Youssef Nabil is an artist based in paris.

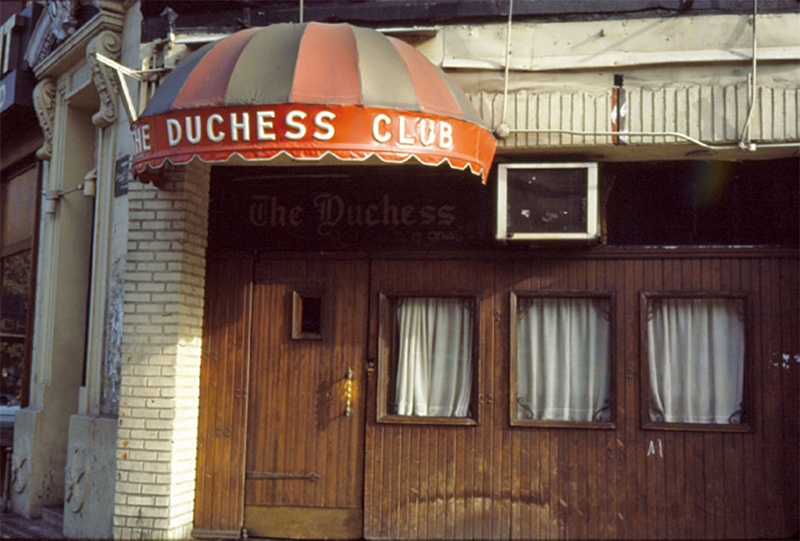

The Duchess Club, Grove Street, New York, ca. 1980s. Photo: Lesbian Herstory Archives.

EILEEN MYLES

The Duchess in Sheridan Square, 1979. I spent time there in the first few years I was in New York. It was a very mixed-class bar, which gave the impression that once you dove into the lesbian realm your sense of time and place got lost. Lots of women looked very bridge-and-tunnel which I didn’t like since I had come to New York to be a poet and meet artists and that wasn’t the scene in the Duchess. Basically it was anyone who was gay, which didn’t imply a specific style or social class. But my strongest memory was the night I completely drunk threw a drink in the face of my then girlfriend who was cheating on me. I had just gotten my first grant that day and I was out celebrating. I was very quickly thrown out of the Duchess (and even barred from drinking there for a while) by a short but very tough butch who of course I was yelling and swearing at but nonetheless I landed out there on the sidewalk on my ass like in cartoons.

For the purposes of writing another Stonewall piece, I’ve been researching Stormé DeLarverie, the swank bulldagger who famously threw the first punch at Stonewall, and apparently she was working at the Duchess ten years later (as a bouncer) at the same time I was thrown out, so I’m pretty sure it was her.

Eileen Myles is a poet, novelist, and art journalist in New York. Their most recent book of poems is Evolution (Grove press, 2018).

JACOLBY SATTERWHITE

One fun memory I have of queer nightlife was the time Grindr and Visionaire commissioned me to “activate” a room at the Standard High Line in New York. I wallpapered the place with a CGI rendering of a Central Park cruising site, filled the jacuzzi with vodka bottles in paper bags, and sent around platters of poppers and other party favors. Patrons were invited to dress up in major clothes and hardware from the David Casavant Archive and perform transgressions in front of my green screen until eight in the morning. That party was the origin of all sorts of myths: There were tears, drugs, notorious fights. Also, I left with eight hours of footage of some of the most inspirational bodies, which I later made into art.

Jacolby Satterwhite is an artist based in New York.

Gay Liberation Front pin-back button, ca. 1970.

CATHERINE OPIE

In the summer of 1983 in San Francisco, at a bar on Valencia Street called Amelia’s, I came into my community of sapphic sisterhood. Thursday night was the ritual dancing to Joan Armatrading and Sister Sledge’s “We Are Family” with more disco thrown in. We waved our hands in the air, pressed our bodies gleaming with sweat against others, and talked about who was hot in all leather. We could be our true selves: Softball-playing lesbians mixed with the leather-clad crew—all were permitted. Good music in a safe space was formative to my identity, to getting brave and coming out. I was there to watch first—and then to cruise.

Catherine Opie is an artist based in Los Angeles

JOHN WATERS

The first gay bar I went to was in Washington, DC, and so square. I thought, “I might be queer but I’m sure not this.” I wanted to be in a Stonewall-type bar—drag queens, hustlers, and other angry perverts—and I later found such a place in Baltimore. It was called Pepper Hill and was located right next to the main police station. I was looking for a riot in those days but alas, that never happened here in gay dives.

John Waters is an artist, writer, and filmmaker based in Baltimore.

STEWART UOO

I was a shy, timid, asexual, closeted, unformed college-aged art-band member standing outside a Seattle pizza shop at night while on tour in 2009. Across the street, sparkling drag persons stumbled out of a taxi carrying fanciful shopping bags with their hair bouncing in the wind as they paraded past a pack of cheering butch studs and into a gay club. The theater of that moment had me enchanted with joy and a mischievous curiosity that had me wanting more, more, more!

Stewart Uoo is an artist based in New York.

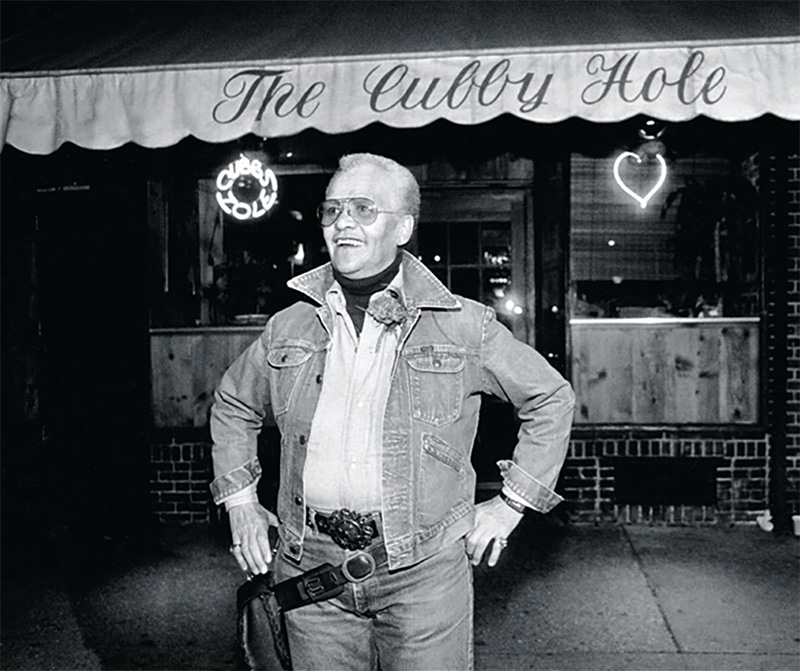

YVONNE RAINER

Vesuvio’s in San Francisco was more “bohemian” than gay. In New York, it was either the Duchess or the Cubbyhole. But I barely remember anything about those places. I have more vivid memories of hanging out in the Cedar Tavern and Max’s Kansas City, but those were definitely not gay bars!

Yvonne Rainer is an artist based in New York.

The Spectrum, Ridgewood, New York, January 26, 2019. Photo: Luis Nieto Dickens.

RAÚL DE NIEVES

gage of the boone and I first connected at a Tracy + The Plastics concert in San Francisco. It was the beginning of a more than fifteen-year friendship that has spanned space and time. He sees the club as a place for community and possibility, and this view has enriched my life in so many ways. We transplanted ourselves to New York, and in 2011 gage started the Spectrum in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, to resist the closure of DIY queer venues in the city. The Spectrum became an incubator, a protected space for queerness and exuberance. My nights there were spent dancing and communing with all those around me. During the day, the location was activated as a studio and workshop. I even found affordable housing in the apartment above! In 2016, it moved to the Dreamhouse in Ridgewood, New York, (which closed in February), and I again experienced all the fervor and joy that nightlife has to offer, on the dance floor and beyond.

Raúl de Nieves is a multimedia artist working and living in Brooklyn, New York.

CHRISTINA QUARLES

If ever I want to bring up an “I knew them when” reference, I’ll most likely be pulling from some night at a queer party—a testament to the innovation, foresight, and creativity bred when we queers get together. Some of my favorites: dancing to Big Freedia in 2009 at Glasslands in Brooklyn; being served apps by Wu Tsang and Ashland Mines at their weekly Wednesday-night party, Grown (at M Bar in LA in 2010); seeing Kelela perform in the basement of a mainstream West Hollywood gay club for the afterparty of the 2012 premiere of Wildness (documenting another infamous party in LA that Wu Tsang and Ashland Mines helped create); seeing Christeene and SSION and House of Ladosha and so many more at Los Globos (LA, 2012) and Light Asylum (Brooklyn, 2010), and Mykki Blanco (2012) and everyone else at Mustache Mondays (La Cita in LA); witnessing a stripper dressed only in an inspiring groin-bandana with artist Tschabalala Self in 2015 at Yale’s favorite after-school hangout, a gay bar that shares its name (not coincidentally) with our class’s 2016 thesis exhibition in New York: Partners.

Christina Quarles is an artist based in Los Angeles.

CHRISTIAN HOLSTAD

It was a warehouse party in Minneapolis in the late 1980s. I passed through a set of curtains and found myself dwarfed by a six-foot-four-inch African American man wearing gold lamé thigh-high platform boots with matching short-shorts and a white Afro wig that enveloped most of his head. As he danced, he raised his arms to the sky in ecstasy, revealing huge clumps of black-light-lit deodorant that matched the wig.

Christian Holstad is an artist based in New York.

JEB (JOAN E. BIREN)

The first lesbian bar I ever went to was Phase 1 in Washington, DC. I remember going there in 1970 with other radical lesbian feminists and dancing all together in a big circle. The women who had been going to the bar for years were dancing in couples and were not pleased to have us taking up their space. It took us a while to learn to respect the codes and customs of working-class bar culture.

JEB (Joan E. Biren) is a photographer and filmmaker who keeps trying to retire and a social justice activist who will never retire.

PAUL MPAGI SEPUYA

I came out in 1995. I was thirteen. I don’t recall my first gay bar, but I remember my first gay coffee shop, Third Rock, in San Bernardino, California. We were in high school and wearing handmade rainbow-bead necklaces. I remember people of all ages, a pool table, sofas. Then there was that party . . . was it TigerHeat? In West Hollywood? Also all ages. In New York, I remember going to Kurfew, “America’s Largest Young Gay Dance Party,” at the Tunnel nightclub just before it closed. Somewhere on Third Avenue above Fourteenth Street I remember seeing Amanda Lepore for the first time. The thing I had wanted to see most on my first visit to New York was David LaChapelle’s portrait of Lepore as Marilyn at Tony Shafrazi Gallery in SoHo. Third Avenue and Third Rock.

Paul Mpagi Sepuya is an artist based in Los Angeles.

Bonnie and Clyde, West 3rd Street, New York, ca. 1980s. Photo: Lesbian Herstory Archives.

AMY SILLMAN

In 1973, we frequented Augie’s at 3729 North Halsted in Chicago’s North Side. It was full of women who were way older than us: We looked more like little Andrea Dworkin spin-offs in shapeless flannel and denim overalls, with hair that was cut with a kitchen knife. They were like butch versions of Cher, sleek, tan white women with acrylic-influenced clothing and hair, all teased and shaped into immobile forms with Aqua Net. They wore tight, clingy shirts with loud patterns, and high-waisted trousers that showed off their flat stomachs and lithe hips. They had thin gold belts that weren’t ironic. They actually knew the Hustle.

Then in 1975, still a kid, I hit New York: Everything was cooler there. We went to Bonnie & Clyde’s at 82 West Third Street, where a much more diverse crowd of black and white lesbians mingled and crushed: fierce downtowners, poseurs, incredible dancers, scenesters, divas, stone butches, and jaw-dropper phallic femmes with sideways caps and weaponized nails. Their style was off the charts, way better than anything I’d seen in Chi-town. I was ashamed of my midwestern attire. If I ever learned to be a dandy it was there, where dancing meant getting out on the floor and fully commanding your little piece of ground, showing off your micromoves made unsmilingly as though you couldn’t care less, entirely blasé, an attitude of precise auratic indifference, which by the way I found later could be combined to some effect with dorky midwestern clothing.

Amy Sillman is an artist based in New York.