- Source: BOMB MAGAZINE

- Author: MELISSA JOSEPH

- Date: DECEMBER 6, 2021

- Format: ONLINE

Chucka-chucka-chucka-poom-poom: Kenny Rivero Interviewed by Melissa Joseph

On learning not to paint when he (we?) should be looking.

Kenny Rivero, Downstate Tap (Aqueduct), 2021, acrylic, oil pastel, color pencil, and oil on canvas, 72 × 72 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Matthew Brown.

Kenny Rivero contains multitudes. And sometimes he paints. The surfaces of his work provide glimpses into the many worlds he traverses in a day. While he may appear to embody contradictions, a more accurate take may be that the infrastructures of these spaces can’t keep up with the pace at which he is moving through them. I was lucky enough to cross paths with him during his current exhibition, Bad Picture of Me, Good Picture of Us, at Matthew Brown in Los Angeles.

Melissa Joseph

So you don’t consider yourself a painter. Let’s start there.

Kenny Rivero

I like believing that painting is something that I am doing versus something that I am. l think my practice has more origins in my curiosity about things, and that goes beyond painting. Painting is just the best way I know how to speak. It’s where I can flex, and show off, and be vulnerable and shy, and do things I can’t do with drawing, let’s say.

MJ

But you just did a show of drawings.

KR

That was a challenge. The drawings say too much that isn’t meant to be read, and I don’t know how I feel about having to share so much personal information.

MJ

Aren’t we captured by surveillance video like eighty percent of the time we are outside? What is privacy, anyway?

KR

I guess I have a romantic idea about what privacy means that’s not realistic. I want there to be a secret. I want to have secrets!

MJ

And your secrets are in your drawings?

KR

Yeah. I don’t edit my drawings like my paintings. I am very aware of the painting being a “seen” thing, and I like that game. The drawings are meant for an intimate presentation where people get a sense of their objecthood. They are meant to be touched, to fall apart and have a lifespan.

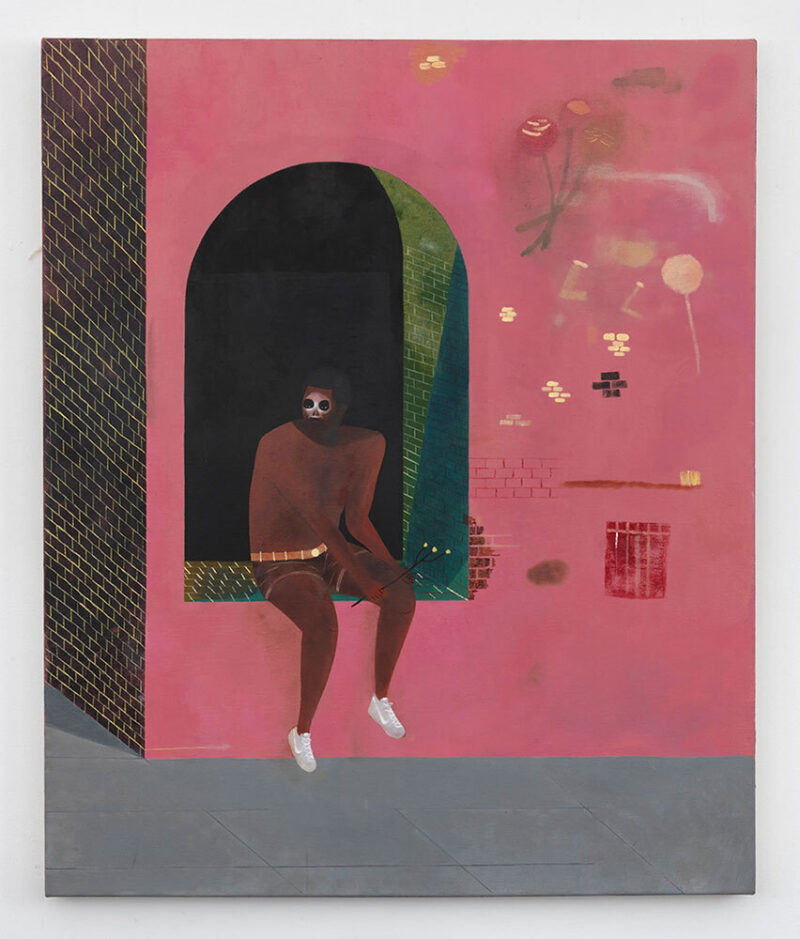

Kenny Rivero, A Watcher, 2021, oil on canvas, 36.25 × 30 inches. Photo by Adam Reich. Courtesy of the artist and Matthew Brown.

MJ

I want to talk about why I wanted to interview you. I recently read a profile about you that felt flat and uncharacteristic. Has anyone ever captured you in a way you feel is authentic?

KR

Rarely someone on the strength of their own interest who wanted to unpack the more nuanced stuff. It tends to be the Cinderella narrative of me coming from the Heights [Washington Heights in New York City] or that my life started when I was a doorman or a custodian at Zwirner.

I did an interview once and the first question was, “So give me the dirt on Zwirner.” That’s the tricky thing about it. I value those experiences, but it isn’t everything. What if I was white? Then it wouldn’t be that important. Or if I wasn’t from New York? I take that part of my identity seriously and want it to be out in the world, but not in a gross way. One article actually said I was “from the mean streets of New York” in there somewhere.

MJ

Perhaps a cheesy hook and not a judgment?

KR

Of course, but it’s reductive! Again, it’s not that I don’t want that to be part of the story; it is, but it’s also…. When do I get to talk about Legos?

MJ

Right now! Legos: go.

KR

I love Legos! The first set I ever completed from start to finish was a Millennium Falcon last year that I got as a gift. As a kid, I only had hand-me-down Legos. My world building, how different kinds of worlds collapse into each other, comes from playing with Legos, GI Joes, and any toy I could get. I had a Lando Calrissian figure for forever from my brother’s friend. I used to create circumstances for my toys to exist together, and I had this system about introducing new toys to old toys and how they had to build together before I could play with them together. I feel like that is what I am doing in the studio.

MJ

Tell us about the new work.

KR

They’re different because they were started at different points in the last few years: either brand new or works that I never finished. They’re remnants, outlaws of the studio that came together somehow.

MJ

Misfit toys!

KR

Yeah, misfit toys that I am trying to introduce to each other! I never thought about these things. I wanna cry. It’s been hard thinking about this show coming together because I have less control with them. Sometimes it feels like a chore to work on them because of how demanding they are.

MJ

People don’t talk about that enough. There is an idealized notion of painters in their studios.

KR

I want people to know how painful it can be. The investment required changes every single day. I can be painting, and it’s literally fighting me like, “Why am I touching this right now?” Working on multiple things helps me keep that in check, so I don’t paint when I should be looking. That’s been a hard lesson with these paintings because I want them to realize themselves already. That urgency paired with having to resist is the tension that I am having with them.

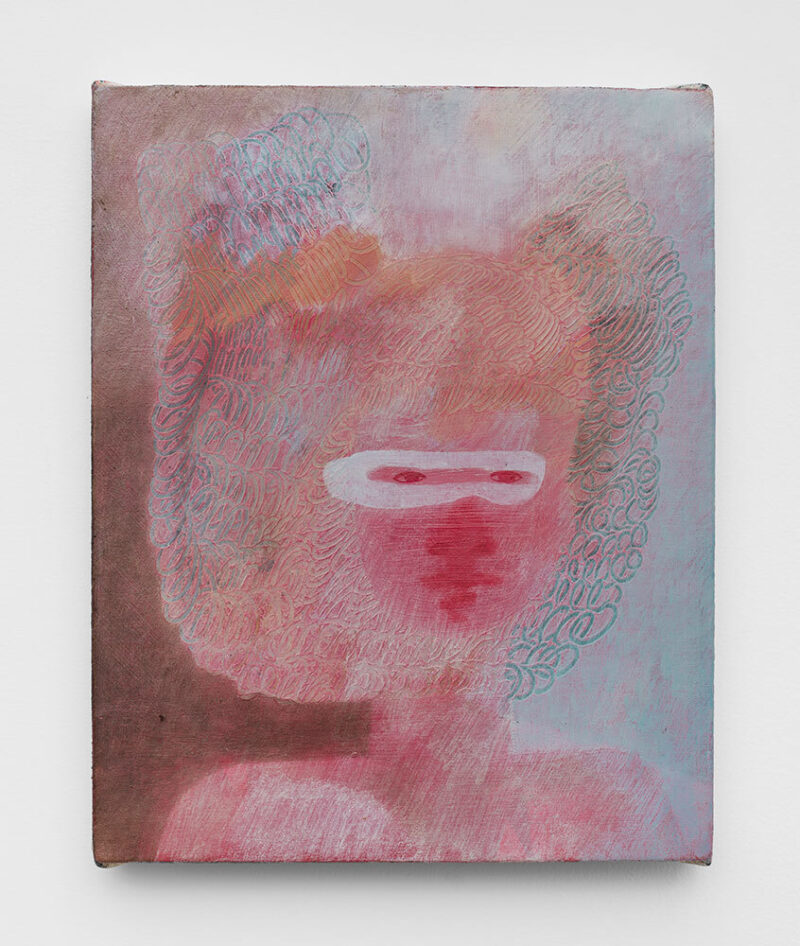

Kenny Rivero, Sheep Thief: First Gen, 2021, oil on canvas stretched over panel, 10.25 × 8 inches. Photo by Adam Reich. Courtesy of the artist and Matthew Brown.

MJ

Can you talk about where your painting sensibility comes from?

KR

I took painting with Jack Whitten at the School of Visual Arts, and he got us thinking about plasticity and what paint means as an object, not just as a color device, and my brain exploded! I realized I’d been steeped in painting forever. Thinking about the walls of the apartment I grew up in, it was the first time that I saw them as a painting, as a verb or happening, or an accumulation of different people’s lives on a surface.

I love R. B. Kitaj’s ideas around being in multiple worlds at once while being a painter. Home becomes this abstract idea that’s never really there. Thinking of New York or the DR [Dominican Republic] as home feels too fragile to trust somehow. I’m realizing that my studio is more home than anything, that my practice, me making work and being invested in and bearing the burden of these ideas, that is home.

MJ

You’re fusing images of your mother with Wolverine and your aunt with Cyclops. What’s motivating that?

KR

For a long time I was working with Batman. When I got to grad school, I started to question the politics of Batman, and it just didn’t sit well with me. One of the first paintings I did is of me assassinating Bruce Wayne. Now every time I draw Batman, it’s not about justice in the same way. It’s more rooted in Afro-Caribbean faith systems and how that world operates.

Wolverine as my mom and Cyclops as my aunt allow me to play around with the idea again. My aunt was into divination, so Cyclops was about her having this energy that projects from a third eye that’s not for destroying but rather having vision.

Wolverine is stubborn and doesn’t always consider the consequences of getting hurt. His healing ability comes at the cost of his memory retention, which for me echoes narratives of diaspora. My mom grew up in a dictatorship. She had to create this body mask in order to survive, and then, coming to this country, she had to do that in a different way because language separated her from the American Black experience. She and Wolverine both lived several generations in their own lifetimes.

Kenny Rivero, No Fuémo, 2014, collage, watercolor, and graphite on reclaimed paper. 8.25 × 5.75 inches. Photo by Adam Reich. Courtesy of the artist and Matthew Brown.

MJ

What is important for people to know about you?

KR

That I’m curious more than I am interested in making statements. Things I’m sharing aren’t about answers, just more questions. I see paintings as constantly moving, not necessarily completed. I’m curious about learning from them and seeing how they adjust the way I look at other things.

MJ

You’ve mentioned a pull toward abstraction. I don’t see this as a far jump from how your paintings begin and end.

KR

Figuration has always been something that I gravitated toward because of how it lends itself to narrative and how I can tell a story through the body about how bodies engage with space and each other. Much of the process of painting and image-finding is through abstraction, but the narrative has always been easier to talk about.

MJ

I see your figures as psychological spaces.

KR

But am I an abstract painter?

MJ

Do you need to label it?

KR

No, but in a lot of ways I am leading the conversation away from abstraction except when I talk about my process of beginning a painting. It’s all intuition within a very specific structure. I start pushing around material where there’s just a color I am interested in or a texture, and then this weird thing happens where I am thinking more like a musician. Maybe it’s a rhythm or pace, or how I’m scuffling with the brush. Chucka-chucka-chucka-poom-poom.

MJ

Wish me luck transcribing that.

KR

It’s p-o-o-m, not boom. Is Kitaj an abstract painter?

MJ

He’s in a relationship with abstraction, sure. You are too.

KR

That’s where I see these: as a circumstance of paint on a surface. But there’s imagery that occupies more space. I have always seen it as me having to make a choice, like I can’t have both, but I want both.