- Source: ART REVIEW

- Author: KIM CORDOVA

- Date: SEPTEMBER, 2016

- Format: PRINT

CHELSEA CULPRIT MISS UNIVERSE

Yautepec, Mexico City, 7 July-9 September

Chelsea Culprit’s Miss Universe reimagines the titular parade of competitive objectification as the psychic mise-en-scène of a strip-club locker room, strewn with all the defences, reconciliations and intimacies needed to survive the pressure to perform.

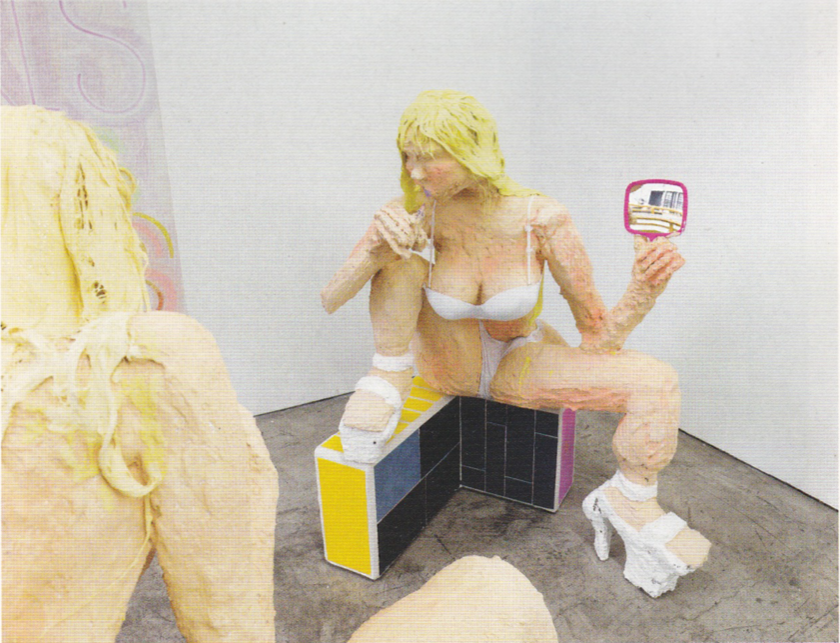

In paintings and larger-than-life sculptures of backstage dancers in thongs and bras, Culprit works to dismantle the basic-arithmetic economics of desire: more is more is more. Eschewing the soft-focus of finish-fetish, she presents stubbly figures made of painted cement, high-density foam and sand, with rough skin, thick calves, extra arms and platform dance shoes that while theoretically meant to elevate them, visually weigh them down.

Though the women are offstage and indifferent to our gaze, I struggle to see them as liberated figures, even in these moments of locker-room intimacy. A sculpture of an almost faceless woman in a silver plastic dress with ‘tickle-window’ cutouts reclines, endlessly pouring herself a Red Bull through a fountain pump in the can. Titled Tired of Being Tired (all works 2016), her exhaustion defines her. A few feet away, the dwarfed flame of a votive candle flickers in the Elephant Man-like hands of Her Fire, a woman frozen in the act of trying to light herself a menthol cigarette. Behind both women a painting proclaiming GIRLS GIRLS GIRLS mimics a flashing neon sign in a window covered with tinfoil security bars suggesting a prison or a circuit. Think Peter Halley gone to the porn shop.

Using the skin trade as an allegory for labour in general, Miss Universe offers no illusions of a world where women are safe and comfortable to self-actualize as they chose. There’s exhaustion in here, as well as pathos, hunger and confusion. Self-tanner is slathered, lipstick applied, extensions clipped in, caffeine, nicotine, taurine and sugar guzzled and huffed. They may not be performing, but these women are preparing to work.

Culprit’s mixed-media paintings on canvas further her exploration of the difficulty in women’s labour politics to have a pizza and eat it too. Rendered in the red colour of peepshow lights, her figures’ limbs are jammed into the corners, taking up all the space of the window-size picture plane with their big colour, furious movement and cheeky jokes. In Double Happiness, a woman with two sets of breasts struggles with chopsticks while attempting to eat Chinese takeout, the packaging branded with the Chinese logogram for marriage. In Cheeseburger in Paradise we see a contortionist endeavor to eat the Jimmy Buffet pun off the grill menu at every strip joint with a fluorescent ‘Paradise’ sign blinking over the door.

Niche preferences and advertisements aside, chimeras of eros generally don’t settle down to a Big Mac or pour themselves a Red Bull, as their imagined lack of need or agency is crucial to the escapism of the business of fantasy. The presence of fast food in Culprit’s paintings and its detailed rendering as focal point disrupts the spell of the stage by reinforcing her subjects’ humanity via their hunger and their hurriedness.

Yet not one of these cement or painted women completes the action she is setting out to do: her cigarette is unlit, they aren’t actually eating, the drink never meets her lips. Is Culprit commenting on the cracks in a system that encourages women to ‘lean in’, yet rewards them with a 21.7 percent pay gap? Is she holding caucus on the Sisyphean effort of just getting emotional complexity of in-between moments?

Miss Universe attempts to tap into the tragedy of a club once the lights have been turned up and the magic blown out, but while Culprit may be showing craft-be-damned four-meter-tall sculptures of strippers, they are more mannerist than grotesque, shocking or even monumental. However, the earnestness with which she recasts her protagonists as unglorified, unsentimental workers trying to get through a shift is her most powerful through-line. They seem to ask: if labour dictates value, and if gender, like labour, is performative work, what is the value of the effort that goes into putting on labour’s performance? Is invisible work worth less just because it’s invisible?

Fake twins with Fake Tans (detail), 2016, mixed media, dimensions variable.

Photo: PJ Rountree. Courtesy the artist and Yautepec, Mexico City.