- Source: THE BROOKLYN RAIL

- Author: ASHTON COOPER

- Date: APRIL 2016

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

CHELSEA CULPRIT

BLESSED WITH A JOB

The art historical canon is chock full of fallen women, Jezebels, and harlots, from Degas’s ballerinas to Picasso’s demoiselles. Whether they were actually being employed as artists’ models or captured as they went about their daily lives, women outside the realm of respectability have indelibly formed Western culture’s image of “woman.” In her 1992 book The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity and Sexuality, Lynda Nead writes, “The female nude not only proposes particular definitions of the female body, but also sets in place specific norms of viewing and viewers.” The Chicago-based artist Chelsea Culprit’s exhibition of paintings (and two sculptures) at Chicago-turned-New York gallery Queer Thoughts, tackles these histories of representation. The setting for Culprit’s portraits of women is the strip club, a space where she worked as a dancer ten years ago. Culprit’s paintings come from her lived experience, as if Manet’s Olympia had started making images of her own life.

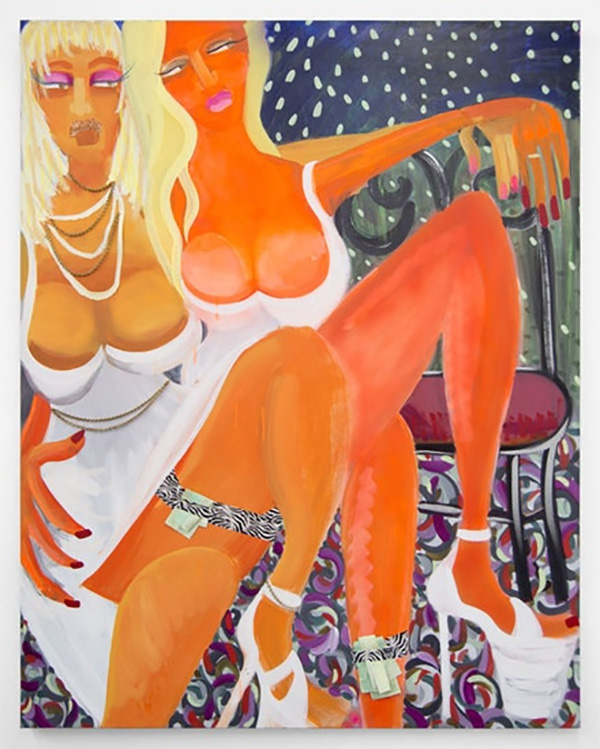

Chelsea Culprit, Fake Twins with Spray Tans, 2016. Oil and mixed media on canvas. 60 × 48 inches. Courtesy Queer Thoughts.

Culprit is one of many young women artists, from Mira Dancy to Amy Bessone, who are consciously choosing painting as the right arena to think over the iconography of the “female.” Just this week, I received a press release for a show of four women who are all painting abstract-y female nudes and are supposedly “beyond the gaze.” This conceit makes me feel uneasy. Just because women are painting women doesn’t mean we’ve somehow moved beyond the gaze, beyond “norms of viewing and viewers.” Rather than aping historical tropes, the work must create a new language that pushes viewers beyond convention. In her show, Culprit uses sculptural elements, camp, and references to reified art historical tropes as tools to begin to dismantle oppressive visual histories.

A large (106-by-75-inch) painting titled Slow Monday (2014 – 16) sets the pace for Culprit’s show—all of the other paintings are hung on its horizon. The oil and mixed media work depicts a bevy of cartoonishly seductive dancers (as well as a manager/pimp figure) looking out at the viewer à la Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. (Picasso seems to be popping up in a lot of young women’s work—from Nina Chanel Abney’s gigantic painting Hothouse (2016), on view in the Whitney’s Flatlands show, which also recalls Les Demoiselles, to recent paintings by Dana DeGiulio that point toward his Synthetic Cubist still lifes.) In Slow Monday, and in most of the works on view, Culprit embeds some of the strategies of sculpture, and even performance, in the canvas surface (using paint as an element of her performances led Culprit to start making paintings five years ago). Sculptural elements, like an actual gold hoop earring or canvas shoes that hang below the stretcher, bring the works into the audience’s space. Viewers must navigate a high heel made of glass with rib-like straps that hangs from a chain just in front of the painting. Beyond these elements, the large size of the works combined with the snug gallery space forces the viewer to confront the women on the walls.

Culprit’s works have a certain campy sense of humor that she uses to undermine the high art nude’s circumscriptions of the body. In her 1964 essay “Notes on ‘Camp,’” Susan Sontag writes that “the essence of Camp is its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.” She goes on to say that “Camp sees everything in quotation marks. It’s not a lamp, but a ‘lamp;’ not a woman, but a ‘woman.’ To perceive Camp in objects and persons is to understand Being-as-Playing-a-Role. It is the farthest extension, in sensibility, of the metaphor of life as theater.” Culprit is exposing the fraught landscape of gender normativity through the artifice of the represented, sexualized woman. She uses camp to undo codes of sexiness. For example, in Elektra (2016), the figure’s breast is pierced with an actual nipple ring while her faux leather thigh high boots spill out of the canvas to form a bulging sculptural element underneath. In Fake Twins with Fake Tans (2016), fake money is adhered to the canvas surface as if it had been slipped into the underwear of the woman depicted.

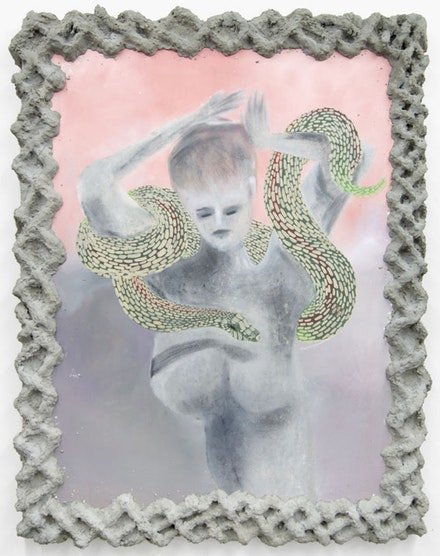

Chelsea Culprit, Midnight (2014 – 16). Oil on canvas with cement frame. 64 × 50 inches. Courtesy Queer Thoughts.

Midnight (2014 – 16) tackles the trope of women with snakes. The oil on canvas work, which portrays a gray figure with a snake entwined around its arms and upper body, feels like a reference to Laocoön but of course the serpent also looms large for the original fallen woman Eve, Medusa, and Cleopatra, who legendarily committed suicide via asp. The work has a chunky, twisty frame fashioned from cement, which at moments splatters onto the canvas itself, making a case for messiness and indeterminacy. The primary figure itself is painted with a kind of gray cotton candy-like fuzziness. Its large bosom could point to its femaleness but could also be pecs in the vein of Michelangelo’s muscle-clad women. Here, again, the figure is “not a woman, but a ‘woman’,” not an Eve, but an “Eve.”

Culprit also makes reference to Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, who painted well-heeled prostitutes on the streets of Berlin the year before WWI began. Kirchner emphasized that he was painting from life, from “real” women, but Culprit’s painted images are mediated by ten years of memory, giving us the understanding that what we are seeing is fiction as much as it is truth. Kirchner’s anxiety about urbanization and modernization is projected onto the bodies of the women he paints. If Kirchner was using women’s bodies as containers for his own anxiety, Culprit is displaying the way that oppressive social forces and norms are inscribed on the body, the way that our very bodies act as archives for oppressive images and normative cultural regulations. By making reference to histories of painting but undermining them through a strategy of camp, Culprit is working through how a woman painter might begin to undo how we see and understand images of women.