- Source: DOCUMENT JOURNAL

- Author: KEN LAYNE

- Date: JANUARY 2, 2023

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

Chasing divinity in the Mojave Desert

Midnight Sun Horizon, Mojave Desert, California.

For the seeker, the mystic, the artist, the outlaw, the romantic idiot, the allure of the American West endures

The closest I have come to seeing God in the desert (so far) was on Highway 395, south of Lone Pine, California—a December dusk in the Sierra Nevada’s shadow, the year of 9/11.

I was making good time in my old Grand Cherokee, the Cadillac of Jeeps, bought used with the advance on my first book—the first time I’d had wheels in five years. There is nothing so enormous and beautiful as the Eastern Sierra in winter’s fading light, on the most beautiful highway

in America.

In that purple dusk, I saw a jittery light on the horizon, due north. We were somewhere around the Highway 190 turnoff to Death Valley, near the mostly dry Owens Lake; I’ve never figured out exactly where this happened, though I still make that drive a couple of times a year and keep my eyes open. I’d just gotten married again, and my then-wife was in the passenger seat.

The size of the light was changing, and it wouldn’t stay put on the horizon. We both watched it for a while, on a stretch of divided highway with those jagged piles of black lava rock in the median, and talked about what it might be: maybe a radio tower, or a low-flying plane? Right then, it transformed—from a distant light, a curiosity, into this enormous manta ray something hovering over the sand and brush. I was transfixed, barely aware I was still driving 70 miles per hour through the night. Big, solid lights on each corner, and a jerky spotlight beam from its belly. My wife was screaming for me to Pull over! Pull over! But where?

Mojave Meditation I

Purportedly the largest freestanding boulder in the world, Giant Rock stretches seven stories high and covers 5,800 square feet. It has long served as a gathering point for believers, who claim it rests in a spiritual vortex.

I spotted a dirt turnoff with its rancher barbed wire on either side, and a loud, bumpy cattle guard. The thing was still there—much closer now. Menacing, beautiful, hazy at the edges. I could not look away. The Jeep lurched to a stop and I was out the door, running toward it. There were no thoughts in my head beyond, That’s the kind I always wanted to see.

Is that why I’m seeing it? Is it real? What does “real” even mean?

That’s when it disappeared, as I was barely out of the driver’s seat, staring into the void where something fantastic had just arrived from the ether to put on this peculiar display. Now we were blinking into the deep, dark sky, with only a few high clouds still catching a faint glow of the departed daylight. Around one of those clouds, we saw a tiny point of brilliant light make a beautiful, wide arc and vanish for good—like Tinkerbell in the Disney logo. Was that it, too?

The words “ecstasy” and “awe” have lost their real meanings in our dull and disenchanted world. Ecstasy is entrancement, astonishment, insanity! When you come face to face with the Divine, with the Gods. To stand in awe—in dread and veneration. I understood those meanings at that time. They were the only words that approached the experience. Twenty-one years later, I consider it a life-changing moment, even if its meaning remains elusive and its context suspicious.

Wilderness is the original meaning of “desert.” Like so many romantic words, the scientists have stolen it, reclassified it. They turned a term of mystery into a measurement of rainfall.

Rolling Thunder

The geological landscape of Joshua Tree is composed of relict features inherited from the weathering of its past, resulting in the fantastic and seemingly illogical formations that populate it today.

When Jesus commanded his disciples, “Get thee to a desert place, and rest a while,” annual average precipitation was not the point. It was the lack of people, of civilization—that’s why you meditate in the wilderness. That’s why you spend 40 days and 40 nights testing yourself against the wilds, in a hallucinatory battle of wits with the Devil.

In the Middle East of 2,000 years ago, wolves and bears and the majestic Asiatic lion ruled the mountains and forests of Palestine. To walk alone into the wilderness required a determined soul. Hermits, madmen, criminals on the run, holy fools—these were the solo travelers of the ancient desert. The good shepherd, that tireless hero of Jesus’s parables, led his flock to summertime meadows and mountainside forage, far from cultivated lands. The staff, with its hooked end crafted to pull the wandering sheep back on track. The rod, what cops call a billy club, to bash in the skull of any attacker.

The outlaw and the prophet are desert dwellers by necessity—by definition. They live outside the law, outside the bounds of civilization. The wild lands are home for those who cannot follow the rules of man.

Some 70 years ago, an aerospace worker named Frank Antone Martin began to question his Cold War job. A roamer since his orphan days in Ohio, Martin made his way West, laboring in the silver mines, reading Shakespeare and the Bible by firelight in the hobo camps where he often bedded down. The life of a factory employee in working-class Inglewood, California did not speak to his soul—not like those melodious psalms and sonnets did in the desert night. Assembling bomber planes for the Douglas Aircraft Company was not the way.

From concrete and rebar, Martin crafted an enormous Christ in his driveway. He hoped that Grand Canyon National Park would mount it over the Colorado River—North America’s version of Christ the Redeemer. But there were no takers for this crude statue. Los Angeles newspapers named it “the unwanted Christ.”

Double Jesus

Overlooking the high desert town of Yucca Valley is a mass of white sculptures depicting scenes from the life of Christ, amid a carefully tended native plant garden.

Daylight, Dreams, and Echoes

The otherworldly terrain of the Mojave Desert has attracted visitors for centuries, its vastness appealing to those seeking something sublime.

Only a fellow desert mystic like Pastor Eddie Garver could see the beauty—or, at least, the potential notoriety—of the statue. He brought the 10-foot-tall savior to his country gospel church, on five acres of homestead desert hillside in Yucca Valley, California. A week before Easter, 1951, the statue journeyed from Inglewood to the Mojave High Desert, strapped to a flatbed truck and dragged up the slope, its fingers breaking off against the rocks and brush. Pastor Garver was delighted, and offered the sculptor the whole hillside of sand and Joshua trees for a statuary garden, which Martin tended with his deep dedication to world peace—a world without the bomber planes he’d been building for the Pentagon’s wars.

Desert Christ Park is still there, off a side road in Yucca Valley. Martin is buried in Twentynine Palms, just down Highway 62.

The UFO is the religious vision of the technological age. Carl Jung recognized this more quickly than most, dedicating one of his last monographs—Flying Saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Sky, first published in 1959—to the mystery.

The origin of the flying saucer sighting is less important than its symbolism. At the dawn of our own meek Space Age—with nuclear warfare threatening the entire planet—thousands of Americans saw incredible sights in the sky, spinning visions of brilliant color. To Jung, these were the mandalas of Eastern religion. When the saucers hovered or landed, strange people could be found, dressed like superheroes: blue leotards, knee-high boots, flowing golden hair like Norse gods. They spoke of a New Age, of peace, of time. From the beginning, there was a psychic element—inner space, rather than science fiction’s outer space. George Van Tassel got it all.

Like Martin, Van Tassel worked in the aerospace factories of Southern California. He became friendly with a hermit who mostly lived under a rock on the north end of Yucca Valley—an eccentric character named Frank Critzer. After that hermit was killed by sheriff’s deputies in his own home in 1942, Van Tassel decided to take over his strange encampment.

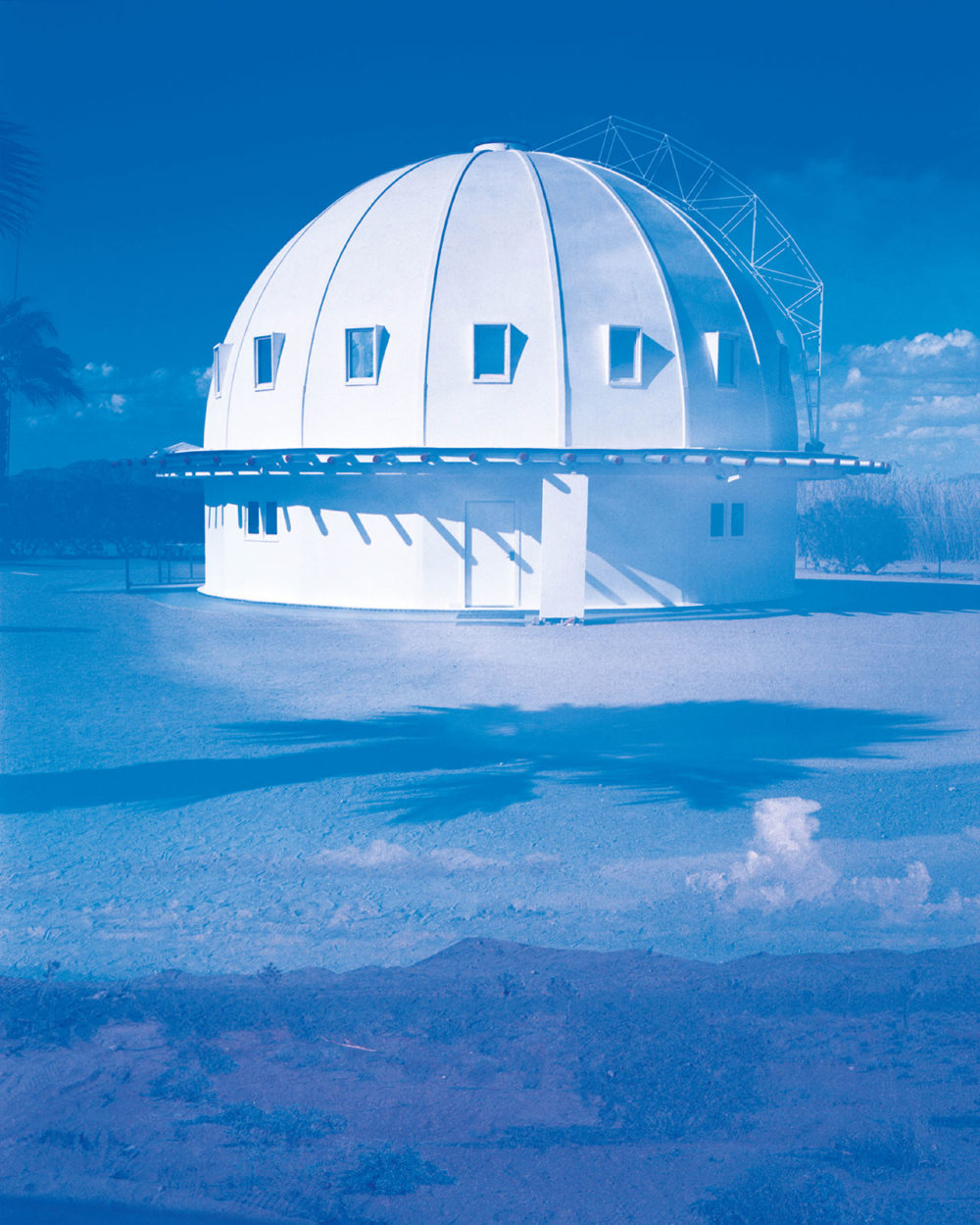

Integratron II

Erected in 1959, the Integratron is a 38-foot-tall cupola-like structure. It was designed from plans its creator-ufologist George Van Tassel—claimed he received telepathically from extraterrestrials.

He quit Hughes Aviation and moved his family to Giant Rock, where by 1953, this Ohio native (who looked like Gerald Ford) had become a practicing mystic: meditation nights under the seven-story-tall boulder, UFO sightings, and regular channelings of a “tall, Nordic” savior entity called Ashtar.

Van Tassel spent 25 years hosting annual outdoor flying saucer conventions at Giant Rock that attracted crowds of up to 12,000 believers, and building his alleged immortality machine, the Integratron—now a tourist spot, north of Joshua Tree National Park, which hosts sound experiences. Van Tassel died of an earthly heart attack in 1978.

Desert visionaries rarely have the resources of land artist Michael Heizer, who somehow burned through $40 million and 50 years building his City megalith in rural Lincoln County, Nevada. Martin built his massive concrete statues of Jesus and the apostles with spare change and Bible church offerings. Van Tassel did wonders with hundred-dollar donations from friends and supporters, remembered in small bronze plaques that remain at the site of the Integratron. But none of these projects would exist without the determination of the solitary desert mystic: Heizer may not have met Venusians, but his lifelong sense of mission is typical of the desert loner, overcome by mysterious illumination. “This land is in my blood,” he repeats in an August 2022 New York Times feature on the completion of City, now within Basin and Range National Monument, east of Area 51, where he has lived and worked for most of his life.

At the western edge of the Great Basin, beneath the wild and jagged wall of the Sierra Nevada, Mary Hunter Austin spent years among the Paiute tribes and pocket miners of Owens Valley. She conversed with the corvids and walked endless miles through shimmering heat. She gave in to it completely, becoming as mystic as the natives who reluctantly told their tales to this strange young woman from the flatlands of Illinois. “After a time you get the point of view of gods about these things to save you from being too pitiful,” she wrote in her 1903 classic, The Land of Little Rain.

Prophecy

The largest and youngest in its volcanic field, Death Valley’s Ubehebe crater is lined with colorful sediments made from streams of limestone, mudstone, quartzite, and volcanic cobbles.

The epiphanies of Austin were of a color and depth unknown to our age of Instagram banalities about Joshua trees: “Tormented, thin forests of it stalk drearily in the high mesas […] The yucca bristles with bayonet-pointed leaves, dull green, growing shaggy with age, tipped with panicles of fetid, greenish bloom. After death, which is slow, the ghostly hollow network of its woody skeleton, with hardly the power to rot, makes the moonlight fearful.”

The somber acknowledgment of the desert’s brutality is the desert mystic’s special burden; it’s what creates its bittersweet sense of eternity. Whatever magic one encounters is littered with death and deprivation. The divine is aware but indifferent. From the age of five, Austin had frequent visions, and conversed with an “I-Mary,” who she credited as the author of her trance writings.

The home she designed in Independence, California—a tiny 19th-century town on Highway 395—is a historic landmark today. The surname Austin was the result of her marriage, which ended in 1905 when she moved to the bohemian colony of Carmel-by-the-Sea, and Stafford Wallace Austin went to Death Valley. Looming over Independence is the Sierra peak that now bears her name, part of the rugged John Muir Wilderness.

Even the paradise of Carmel could not keep Austin from the desert. She wound up in Taos, New Mexico, that ancient pueblo center that has long drawn the world’s mystics, and in 1930 published, in collaboration with Ansel Adams, her last major work, Taos Pueblo—prized especially for Adams’s eerie, monolithic photos that today bring to mind Heizer’s City.

Carl Jung knew the power of raw nature and preindustrial magic better than any 20th-century European. His search for human meaning took him from Africa to India to the same landscape that lured J. Robert Oppenheimer and Georgia O’Keeffe: the ancient pueblos and enchanted wildlands of New Mexico.

Sound Silence

In the year 2000, an earthquake split Giant Rock in two, exposing its white granite interior. A group of spiritual thinkers interpreted its fracturing as a message from Mother Earth herself.

Jung lived a life of prophetic dreams and paranormal coincidence, from his earliest years of consciousness. Finding his psychiatry patients sickened by the suffocating disenchantment of modern life, he sought answers in wild nature, archetypal images, and preindustrial societies. Taos had already been tamed by cultured tourists, watching the Corn Dance—“hungrily too, with reverence,” as Carmel poet Robinson Jeffers put it. But a century ago, it was still more like the 1500s than any other permanent settlement in the 48 states.

During Jung’s travels through the American West, from late 1924 into 1925, he was part of the Taos-Santa Fe zeitgeist: artists and thinkers and hangers-on, entranced by a landscape and culture that had long moved on to a very different timeline. Jung had a memorable conversation with Taos pueblo elder Ochwiay Biano, regarding the busy visitors who flocked to his ancient land.

“The whites always want something, they are always uneasy and restless,” said the elder, identified by his English name Chief Mountain Lake in Jung’s autobiography, Memories, Dreams, Reflections.

I don’t know what I saw two decades ago on the 395, and it hardly matters. I can’t do anything about it—whether it was a holographic projection by some secret military unit, or space people from wherever they’re from now, or an interdimensional entity, or whatever theory you can enjoy tonight on the internet. It seemed to be not only “intelligently controlled,” in UFO speak, but also alive. It noticed me from afar—just another driver on the road to Sierra ski resorts during the winter holidays—and then it was right there, like some living, electrical plasma with its great, weird eye jerking around. And as soon as I got out of the car, it was gone. Look at me, and wonder.

That’s what’s stayed with me in the years since: a sense of wonder, a lessening of cynicism, and an awareness of the wild possibilities within this life, this reality. Living without any real-world acknowledgement of the supernatural—whether religious or folkloric or the usual combination of both—is a very new development for humanity, barely a century out of 300,000 years of homo sapiens.

Dawn of a New Age

The Mojave Desert is characterized by extreme temperatures, swinging violently from biting cold to vehement heat under the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada mountains.

While I’ve yet to experience anything like that again, there are strange, time-stopped moments just as memorable: coming around a narrow canyon bend to the surprise of a big male coyote, who is just as surprised and disappears up that canyon wall like a bighorn sheep; or standing behind the house at night as three or four baby Mojave cottontails leap over each other in some weird, moonlight game—the purest joy and surprise as they bounce ever higher; or sitting on a hilltop at sundown with the clouds turning five different colors and the ravens passing overhead in a hurry, all yakking about the dusk-time family party before darkness.

The desert still welcomes the seeker, the mystic, the artist, the outlaw, the romantic idiot. Largely the property of the US government around islands of tribal lands, the American desert remains substantially undeveloped once you branch off from the interstates and Sun Belt sprawl of Las Vegas and Phoenix and Albuquerque. There are all-but-abandoned towns in the Great Basin that are too far away for vacation-rental weekenders, and vast public lands in every direction. This patchwork of national parks and monuments and forests—from the San Bernardino Mountains of Southern California to the White Mountains of Central Nevada—is the largest protected desert preserve in the Western Hemisphere, second in size only to Africa’s 20,000-square-mile Namib-Naukluft National Park. You can get lost there pretty easily, and on purpose if you like—on purpose like the Manson Family in the Panamint Range (now part of Death Valley National Park), where Charlie thought they’d find the secret passage to the Underworld, where they’d wait out the apocalypse.

As water for industrial agriculture and exurban development becomes costlier in this thousand-year drought, and as the value of raw desert as a crucial carbon sink becomes better understood, the Southwest might stay much the way it is, long into the next millennium. Which is good news for those seeking God, Yucca Man, E.T., La Llorona—whatever they figure is out there, in the night. The spirits of the night need quiet and darkness.