- Source: Harper's Bazaar

- Author: ELLA ALEXANDER

- Date: November 13, 2020

- Format: DIGITAL

Cauleen Smith: “We’re not human without culture; art saves people”

With work now on show in London, the leading US artist opens up about the capitalist roots of Covid-19 and her post-election fears for the Black community

Cauleen Smith. Photographed by Dustin Aksland

For most artists, it’s a badge of honour to find that their work is as relevant and powerful decades after the initial unveiling. Such achievement is bittersweet for US artist Cauleen Smith, whose acclaimed film, Drylongso, is better understood now than it ever was while it was released in 1998 when she was still at film school.

The plot focuses on an art student who starts photographing Black men out of fear they may soon go extinct, a narrative that feels horribly apt in 2020 following the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor.

“I never expected it to be as relevant now as it was then,” Smith tells us in a Zoom video call from her LA home. “The film has grown in popularity and seems more useful to people now than when I made it – then, it was looked at as a sociological document. I was trying to talk about the different ways people try to save their own lives or try to look after each other.”

Smith’s work is often described as political – and certainly it explores issues of race, identity and feminism – but really what she’s fascinated in is the mundane parts of the way we live, the decisions that humans make on an everyday basis and why that matters. “Outside of the political agenda or specific policies, individuals can practice their lives in a way that can impact the world around them,” she says. “Politics obliterates that, it’s about power. I’m not interested in power or who has it. I’m interested in how we relate to one another in the world that we’re in – that’s what culture is. We’re not human without it. Based on everything I’ve learnt about human history, art saves people time and time again.”

Since Drylongso, the California-born artist has created over 40 films typically accompanied by installations to immerse viewers in her world. She quickly realised that art would afford her more freedom than the often-didactic Hollywood, and decades on she is finally receiving broader recognition. The world is finally on her wavelength.

“It’s an interesting lesson to learn that if you’re consistent in what you do, eventually it’ll be recognised,” she says. “I know I work in an eccentric way, so it’s never surprised me that my work wasn’t well-received or well-understood. There’s enough work now that people can put the disparate things together and see a whole cohering which is a nice reward.”

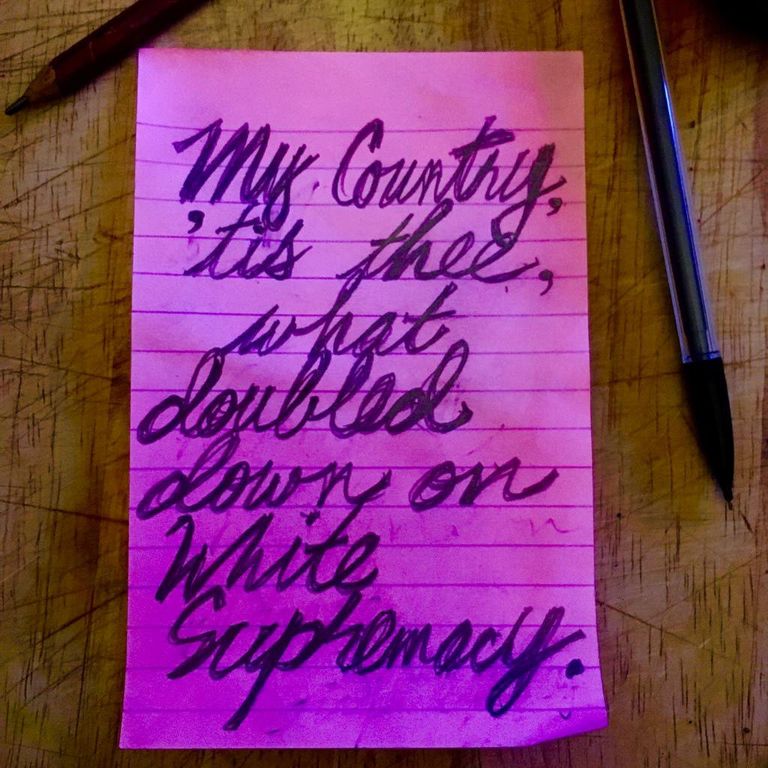

Banners have also become a focus for Smith and formed part of the 2017 Whitney Biennial; on them, she sews words and symbols to represent issues she cares about, be it racism or sexism. In her 2018 film Sojourner, an imagining of a feminist utopia, six beautiful banners appear featuring text by Alice Coltrane, an experimental jazz composer and spiritual leader whose music forms the soundtrack for both films. This year, she launched the Covid Manifesto – a tongue-in-cheek response to gallerists’ attempts to screen her films online without the immersive installation component that is integral to her work. She began scrawling witty missives on lined paper and sharing them on Instagram, only for them to fast gain traction.

“It was around the same time as we were watching our president refuse to acknowledge coronavirus because of economic concerns, she continues. “Apparently, it was ok for millions of people to die just so the stock market’s ok. I think people needed an outlet to laugh. With the scrawling scribble, people would stop to look at it because Instagram is so slick now. It caught people’s eye because it was so crude.”

Courtesy of Cauleen Smith

Public art is important to her and her work is currently on show via the billboards at Piccadilly Circus, as part of a new digital art platform called Circa, created by artist Josef O’Connor and this month curated in collaboration with The Showroom, London. Every evening at precisely 20:20 GMT throughout November, Smith’s Covid Manifesto is projected onto the billboards for the public to muse upon.

“Encountering something accidentally that disrupts your routine or shifts your attention from one thing to another is a good way of giving people something back to themselves,” she says. “Suddenly you think ‘that’s not a coca cola ad’, and that two minutes when you’re trying to figure out what’s happening is a good disruption. It’s nice when something is offered to you and doesn’t want anything back. It doesn’t ask anything of you, it’s just there.”

Smith is characteristically thoughtful when it comes to reflecting on 2020, a year that has been blighted by loss, racial tensions and political unrest. She is grateful that her world “hasn’t fallen apart” in the same way it has done for others, and has spent lockdown in LA, the longest period she’s ever spent at home in 10 years.

“I don’t mind getting on a plane every week; it didn’t feel good at the time and ecologically it was gross,” she says. “There were a few weeks in LA where the skies were blue, and the animals and birds came out because there were no cars. If people weren’t going broke, losing their businesses and dying as a result of a horrible virus, then this would be great. I hate Zoom, you don’t get the same sociality, but you also don’t get this obscene ecological abuse that we were all engaging in before.”

Our ill-treatment of the planet combined with blind capitalism is, what she thinks, has caused the outbreak of Covid-19. “This virus that is killing us lives just fine in bats,” she says. “It doesn’t want to kill its host, but it doesn’t have anywhere to live right now because we’ve taken its habitat from its host and we’ve done that so we can have more toilet paper or something? This irrationality of consumption is at the heart of this, we did this to ourselves. We are not safe on this planet because of the way we’ve treated it.”

She also believes, and it’s hard to argue otherwise, that the pandemic has amplified class and race. “Somehow being rich and white in America means you’re less likely to get this virus,” she says. “I feel a great deal of anxiety to see people put their lives at risk to make a living. That produces a weird psychology where people become defiant about being careful and not wearing a mask because they have to – they have to put their lives at risk anyway.”

In June, a video showing a police officer murder a man called George Floyd went viral. For many, it served as a brutal reminder that systemic racism and police brutality is alive and well, sparking protests around the world.

“Black men and women are routinely killed in the US,” says Smith firmly. “But this year, because everyone’s sitting at home everyone’s suddenly on board with Black Lives Matter? Really, it takes watching a man’s life being extinguished over eight minutes and 46 seconds for you to understand. Does it really take a pandemic for people to care? It’s shameful. People still wouldn’t care about any of this if they didn’t have anything better to do than watch a snuff film.”

Courtesy of Cauleen Smith

Joe Biden’s recent presidential win gives cause for hope that the future might be better. The appointment of Kamala Harris as vice president, the first woman, first Black person, and first South Asian person to assume the role, is equally, if not, more important for the Black community.

“It matters in the way it did when Barack Obama became president,” says Smith. “For my students, they came of age in a world where the US president was an intelligent, charismatic Black man. That’s the world they understand, and they think that’s normal, which is why it matters immeasurably. I see it in my students who are 19 and 20-years-old and they’re confused because this is not the world that they thought they lived in.”

Over the days leading up to Biden’s win, Smith shared a number of impassioned works about the huge numbers of the US population who still pledged allegiance with Trump. More than 72 million people voted for the former reality TV star, nine million more than 2016, meaning Biden won by just over five million. “Everyone knew that it would take a long time to count the votes, but there was hope that there would be a clear, decisive appearance of American voters who said, ‘we don’t want white supremacy, facism and rampant unregulated governments.’ That didn’t happen,” she says. “If Trump had been re-elected, I had been talking to my partner about immigration – we’d discussed where we would move to. We were only five million votes away from that, so I don’t feel safer.”

She is tired, exhausted even, by not only the far-right that have been validated under Trump’s watch, but also by what she calls “wishful liberalism” and those who are still trying to silence and marginalise Black voices when they feel the sentiment has become too extreme. “I’m not mistaken about wanting to defund the police – I want to live. I want my family to live. I want everyone in my world to be safe. I’m not mistaken about that.”

“The posts are a reminder to myself that, while we have beaten back facism for four years, we are in no way out of a dangerous place. We have a four-year reprieve; I wonder what we can do with that.”