- Source: Artreview Magazine

- Author: Ross Simonini

- Date: JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2018

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

Brian Belott, interviewed by Ross Simonini

On Dada, dissonance and what separates a professional artist from the pedestrian artist

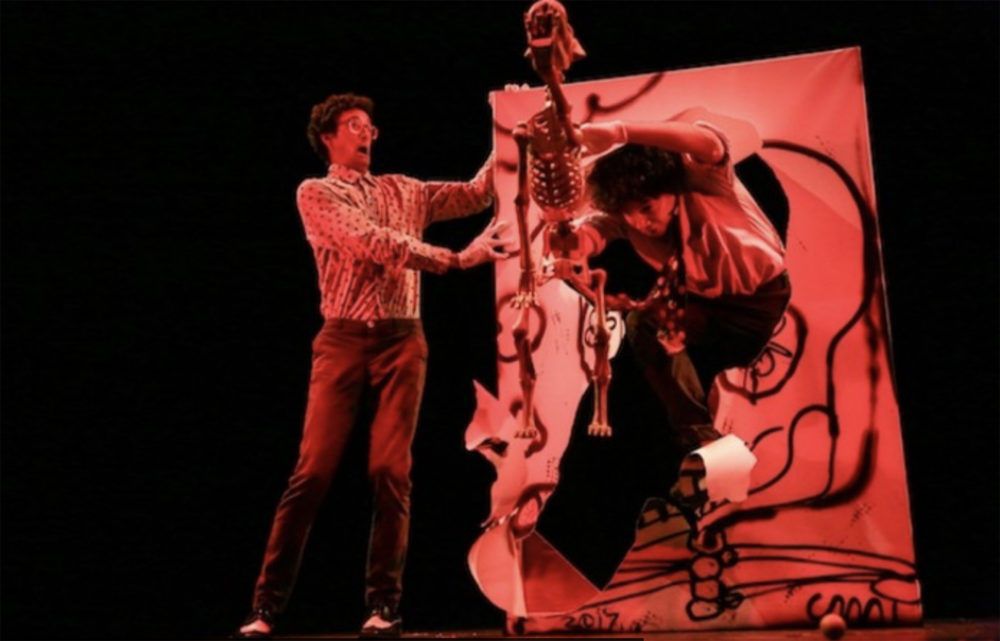

People Pie Pool (detail), 2017, performance. Photo: Chris Sanders. Courtesy Performa 17, New York

In November, Brian Belott performed People Pie Pool, a massive ensemble work commissioned for Performa 17 in New York. The performance involved (in part) five comedians, a handful of basketball players, four academic lecturers, exercise instructors, an improv troupe, dancers, marching bands and an ‘orchestra’ that performed with can openers, golf balls and tissues. In this way, the event recalled a vaudevillesque variety show, alternating between old-fashioned knee-slapping fun and abstract stretches of tumbling, punishing absurdity.

At one point in the evening, Belott staged a parody of an art auction in which paintings by major artists (Joe Bradley, Katherine Bernhardt, Jamian Juliano-Villani, Eddie Martinez, etc – all friends of Belott) were destroyed on stage and run through a paper shredder. Finally, each painting was stuffed into a single plastic pen to be gifted back to each artist. Belott narrated the ordeal with the kind of stuttering, pun-filled nonsense and slapstick humour that characterises many of his performances, including the preposterous ‘fashion show’ held at London’s Serpentine Galleries in 2016. The auction, with its anarchic approach to the market, also recalled the stunt Belott used to raise funds for the event, in which he travelled to various museums in New York (the Whitney, the New Museum, etc) and sold his work for ‘arbitrary’ sums.

Belott identifies his impulses as ‘Dada’ and seeks to invent a perfect mess of an experience, something like what Andy Kaufman achieved for his famed show at Radio City Music Hall in 1979, in which he took the entire audience out for milk and cookies. To do so, Belott often works with a community of artists and friends in New York, including – full disclosure – this author. For People Pie Pool, I conducted a children’s choir while standing in the middle of the audience. I’ve also collaborated and exhibited with Brian, and once, at Performa 15, we (along with 30 other singers) surrounded a ridiculously long dining table of benefactors and demanded to be fed by them.

Belott is also well known for his paintings, which, like his performances, are both thrilling and uncomfortable to experience. He likes to prod his viewer’s sense of good taste with glittery, gaudy colours and childish humour. He usually works in long-term series, most of which collide painting against a collage of dollar-store materials, including socks, wall fans, rocks, calculators, remote controls, marshmallows and hair gel. The work strikes a curious balance between the simple chromatic pleasures of Henri Matisse and the crude energy of art brut.

Belott’s most recent exhibition, Dr. Kid President Jr. (2017), at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise in New York, was a kind of conceptual ‘collage’ of children’s art. For part of the show, Belott forged paintings of his favourite children’s-art. This work sat alongside hundreds of masterful children’s drawings, culled from the astonishing archive of art educator Rhoda Kellogg. The show also included art classes for youth in the surrounding Harlem community, most of whom plastered their own scribbles and finger paintings on the wall.

Together, the onslaught of work created a bewildering soup of authorship that left most viewers unsure of what they were looking at. As he often does, Belott had cloaked himself in the mundane, this time inhabiting the underappreciated artistry of the young, those invisible outsider artists living among us. The gesture was not unlike his approach to recent performances, in which he has transformed himself into a collagist working at the directorial level, an impresario attempting to spin an impossible number of plates just to watch them all come crashing onto the floor.

Brian Belott: What are you doing?

Ross Simonini: I’m calling you.

But you just called a second ago and hung up.

That was an accident.

This is so inprofessional. Let it be known that the interviewer is inprofessional.

I don’t think that’s a word.

It is.

So it’s been a few weeks since we last saw each other at People Pie Pool. What do you make of it all now.

It could’ve been a fever dream for all I know. The whole experience was hell for me. It’s been half a year of working on this goddamned thing. My studio is filled with debris and all I’ve heard in response is ‘good job!’ That’s meaningless to me. I’m too callous for all those niceties. The only comment I remember is, one woman came up to me and said the performance reminded her of The Eric Andre Show [surreal television show on the Cartoon Network’s Adult Swim]. And that’s exactly what I wanted.

Organised chaos.

It’s all mashups and unlikely combos. He’ll have someone who’s doing speed metal vocals against a priest reading from Corinthians.

The same kind of juxtapositions going on in your show.

I’ve been doing this stuff like since high school, since the 80s, collaging people together. I’d do Dada-inspired performances with poets and dancers and a brass quintet scattered in the audience. I wanted to simmer all different attitudes. I wanted a smorgasbord. I wanted endless confusion, and I was obsessed with Dada.

What did you pitch to Performa as the commission?

I told them Charles Ives [composer], Ernie Kovacs [comedian] and the Marx Brothers. That model, the Marx Brothers model, which is essentially three hyper brothers who were all forced into the vaudeville circuit by their pushy mother – this is something I live by. You know how I am. My friends and I have a certain type of brat-pack thing, and at the drop of a hat, I can create a reverberating fugue of calamity with them. Me and [Matthew] Thurber will go nuts and then Billy [Grant] will join in, and for a few seconds you have the Marx Brothers.

You think of a lot of your work through the lens of Dada.

I couldn’t help but think about how Dada is celebrating its 105th birthday. Dada is old. It’s a grandfather, and I wanted to commemorate it. But then I started thinking about people like Stravinsky and Schoenberg. These were revolutionaries. But once they had achieved the badass, transgressive work that put them on the map, both of them went back to making traditional classical music.

Neoclassical. Why do you think they’d do that?

Because keeping your twenty-year-old sharp teeth bared is hard work. Eventually you just want to go back to loving art. And I think that’s an inevitability about being a punk. It’s not a sustainable thing. So commemorating Dadaism is a strange thing. If you’re going to commemorate something that happened in 1915, you know that by now all those punks are old and on their yachts. Maybe the true ones are dead. So the act of historicising Dada is against Dadaism itself. The very notion of Dadaism is an uncontainable wild beast, and now it’s being commemorated? Someone like Tristan Tzara, a wizard, the trailblazing father of it, he knew true Dadas are against Dada. It’s so Tao… or what’s his name?

Lao Tzu.

God bless you.

So how’d you address this?

Well, initially I just wanted people to go crazy onstage, having conniption fits, but I realised that everyone had already seen that. That’s not Dada any more. So I started hiring people who would not be seen as freaks, or punks. Sober-minded people. But the funny thing, the physicist talking about supercolliders, and the lecture about cryptocurrency – these subjects are far out.

Did you actually direct anyone?

I just wanted people to do whatever would excite them most, whatever makes them most comfortable. Wear whatever clothes you like. I think, to make a real event, it has to go beyond the subjective wishes of the director. I tried to make a piece that is beyond my taste. I think that’s an important, generous, dimensional way to make art. Sometimes.

Do you try to do that in your paintings as well?

I do, when I integrate found photography or amateur work, like in the kids-art show, or when I use found sound. I’m always going to grab for what turns me on sensually. But you can also go against that, towards gross subject matter. I think always choosing materials that define your own taste is limiting. It’s just checking a series of boxes, and that’s not what I want to be about as an artist. I think too many artists are just doing what makes them feel good. In my mind, an artist is someone who travels through culture and ideas and attempts to challenge the mind, to go to uncomfortable territories.

Who does that?

[Mike] Kelley. [Bruce] Nauman. Artists that switch it up. They don’t focus on the same material. They try and pick subject matters they don’t understand. And so, to finish what we were talking about earlier, to truly be Dada is to do that, and to be truly Dada would require exploring something totally contrarian to Dada as we know it, like an accountant for the military, or something incredibly dry and horrible. Like someone collecting Coca-Cola memorabilia from the 1930s. That would be Dada. It would have to be opposed to its own history.

Dissonance.

Yeah.

And you could endlessly get off on this dissonance.

Yeah, I guess, until that becomes such a style that I just need to become a solitary artist, like [Giorgio] Morandi, and then I’ll just spend the last 30 years of my life painting still lifes.

The final manoeuvre.

But you have to have an audience for this to work. There have to be expectations you can foil. Otherwise it’s just your inside joke with a small group of friends. Something has to be on record. I’m not interested in art that only three people know about.

But when you leave five-minute long messages on my phone, singing and ranting – that’s a private artwork. It’s on record, but it’s for an audience of one.

Yes, but at the end of the day I’m interested in what separates the professional artist from the pedestrian artist. A grandmother can bring me to tears with her poetry, but she is not an artist. To be an artist, you have to clock in daily, and show your work to a community. Everybody is not an artist.

But what about your children’s art show? You brought kids from the neighbourhood into the space, hung their work on the walls of a major gallery and called it art.

Everyone is an artist until a certain point. Then you pass through the doorway and you have to work to be an artist. What’s interesting about that is that kids who can barely form a sentence can make art as good as any Ab-Ex painters, but then meanwhile, you have all the Ab-Exers drinking themselves to death to try and get back to where the kids were.

When does this door close?

The kid who is thirteen or sixteen will not make as interesting a finger-painting as younger kids.

Do you remember when this change happened for you?

Yeah, I got extremely pretentious. I starting drawing drippy Dalí stuff. The awkward time is when I wanted to grow up too quickly. I think all artists want everything to happen immediately. A kid wants to hurry up and be accepted as an adult, get a car, have sex. It’s how people are. And the hurry-up attitude is also in the parents and the teachers. They’re pushing the kids along. It’s happening now more than ever. People are spending $40,000 on kindergarten! My kid learned the ABCs at 14 months! My kid can spell ‘xylophone’ at 18 months!

But Rhoda Kellogg, for instance, said, no… slow down… leave the kids alone. They can make brilliant art if you just respect them. Do not give them crap materials. Give them expensive materials. It’s amazing what she did. A trailblazing visionary! Her collection is more important than all of Henry Darger’s work, and yet she is unknown. She expanded procedures in classrooms, while that little pervert did nothing.

So how can you celebrate professionalism on one hand and naivete on the other?

You have to draw a line in the sand. An artist is someone who is cursed to make art. It’s not like breathing.

But you’re not cursed to do it professionally. You could walk away at any time. Why don’t you?

It wouldn’t matter! I’d still make art. For instance, some of my favourite work is the sound scribbles that I do. I walk around with a tape recorder and imitate all sorts of personalities, commercials, psyches, musics, genres. So even if I stopped making saleable paintings, I would have to continue to make these sound things. Or else I would hate myself. Or I would have to get into broadcasting or voice acting. I’d have to use my voice or body or colour sense. That’s what I’ve been doomed to do.

In high school I worked at [retro-diner restaurant chain] Johnny Rockets at the mall, and the only way I could survive it was by making up jokes and stories, doing bad breakdancing, speaking in a fake Irish accent to customers. I’d do that even if I was in jail. I’d imitate the warden. It’s the way I process the boring world around me.

Do you remember when you decided you wanted to be professional about art?

I was spoiled. My father was an artist and by example he encouraged me. He had a studio. I spent a lot of time in the darkroom with him. He also painted the house, decorated it, filled it with humour, music and food. His presence as an artist permeated every aspect of how I grew up. And everyone naysayed him. My grandparents told him to get a real job, which only made me want to show them up. I was affected by that. My father really suffered to be an artist. He was cursed. He became an artist when it really wasn’t popular. It was the 1970s. His parents were doctors. He was cursed more than I am.

Could you break the curse? If you made work privately, would that help?

No. It’s necessary to make work and hand it to the community. You have to deal with the frame, the install. You have to learn to talk about it, do the press release and be the face that stands next to the work. Making art alone is only half the job.