- Source: Frieze Magazine

- Author: Evan Moffitt

- Date: March 11, 2016

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

Body Talk:

Jacolby Satterwhite talks to Evan Moffitt about animation, sex and choreography

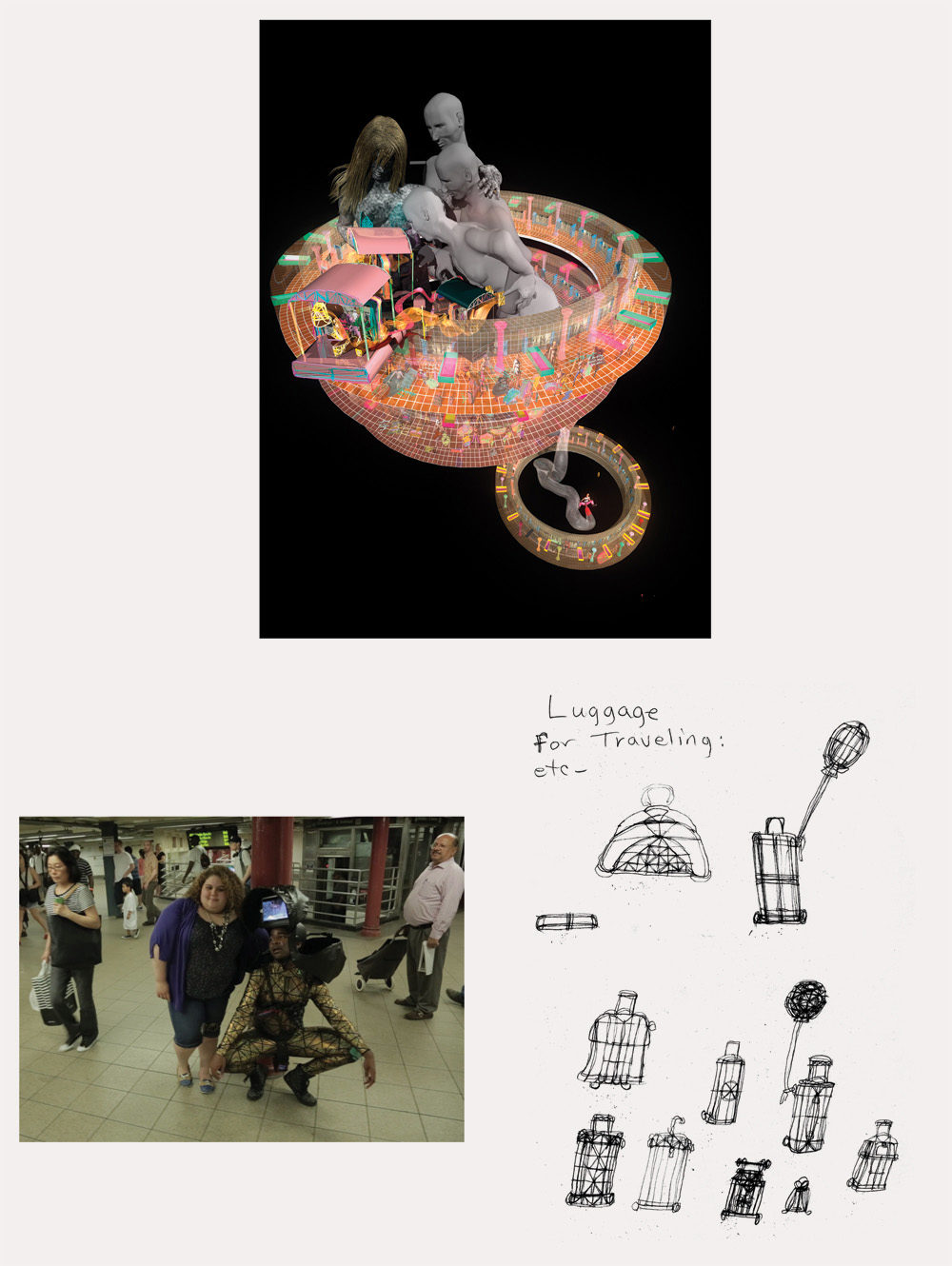

Jacolby Satterwhite’s videos, made with the digital animation software Maya, are filled with seemingly infinite painterly detail. Their frames glide in axial movements like a joystick or drone. In his six-part film suite Reifying Desire (2011–14), Satterwhite’s avatars dance and copulate on platforms floating in vast, star-speckled expanses of mottled purple and brown – a cosmic cyberscape governed by digital technologies that enhance and proscribe sexual pleasure. But the bodies in Satterwhite’s videos are not bionic; they are usually the artist himself, filmed in front of a green screen or in queer performance spaces. Grounding his digital worlds in real ones, Satterwhite explores art history and popular culture, from painting and film to early music videos and club dance styles. Such reference points give his works a political charge that, due to their hypnotic intricacy, is not always readily apparent.

When I sat down with Satterwhite at his Brooklyn apartment, in front of a hacker’s battery of glowing screens and servers, we spoke about the phenomenology of sex, the viscosity of images and the influence of his mother on his artwork.

Reifying Desire 6, 2014, digital collage. Courtesy the artist and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

Evan Moffitt: What is your relationship to painting, and what drove you to digital animation?

Jacolby Satterwhite: As a kid, I was inspired by my mother and by Bible School to draw. I was most familiar with 2D media, even though I was hugely into gaming as well. At art school, I felt like I pushed painting as far as I could but, being an African-American artist and a gay artist, I could not escape the 400 years of oppressive history attached to the medium. Eventually, I threw away all my paints and primers, picked up a camera at Wal-Mart and started to perform in front of it. Around the same time, I watched my mother make the same drawings she had been making since I was a child. She was mentally ill but, over the course of her life, recorded seven albums and made over 10,000 drawings. I saw how, over time, her drawing skills refined themselves, how the line weight shifted. She was making these drawings with an enigmatic language like a Gertrude Stein poem – that’s where the title of my 2014 show, ‘OHWOW’, came from: How Lovely Is Me Being As I Am. I realized that Patricia Satterwhite was the artist hero I should have had all along. So, I decided to make her a rubric for the way I thought about art. That’s why I began performing. The first thing that struck me about my mother’s language was that her words appeared to be scores and, since all of her drawings were about objects, I connected that to the way bodies perform in space.

So, your desire to escape the institutional confines of art history brought you to performance and video, and then, almost paradoxically, back to drawing?

Right. I became more of a dada artist and a fluxus thinker, because I started thinking about chance and language and the surrealist potentiality of mixing incongruent languages together – whether it was the way my mother’s work articulated the function of a spoon, or how a sex toy functions in relation to my own perception of it or to the archives I brought in from a collaboration with another performer. I felt confined by the fact that every gesture I make as an African-American artist would be placed under the umbrella of politics, so I tried being less contrived and didactic. I know that I have a lot of loaded images in my videos, but there are many ways in which to read them. Working with a bareback porn star, for instance, raises the sexual discourse surrounding the preventative HIV medication Truvada; dealing with the work of a mentally ill woman – my mother – brings up the discourse of outsider art. I think that synthesizing these ideas allows me to address things that are naturally gestating within my millennial body.

Making a work with scale and spectacle is like building a computer motherboard. Sometimes, you get lost in the circuitry but, if you look closely, you can get information out of it. Animation can function as a disguise but it’s my job as an artist to warp reality and give the viewer multiple opportunities to expand on as many discourses as they wish, or simply to enjoy the formalism of the work – that triangle or the colour of this light, the viscosity of an image. Because that’s political, too; that’s desire.

Can you talk about your new commission from San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, with Nick Weiss of the electronic duo Teengirl Fantasy?

The album I’ve been producing with Nick involves selecting from over 155 acapella tracks written and recorded by my mother between 1994 and 1998. They’re performed in the folk tradition of the American South – just her singing and tapping her thigh or a pencil on a table as a metronome. And her pet parrot.

Her parrot?

Yes, he was a backing singer. The songs were recorded on a consumer Kmart cassette tape at home between the times my mother spent in a mental institution. We digitized them and have been using every genre of electronic music – dance, noise, drum and bass – in experimental cacophonous arrangements to make as many tracks as possible, which will be pared down to a powerful album. When Nick and I listen to the lyrics and build on my mother’s melodies, I come up with a template of what I want, such as an acid house sound. I visualize my videos so far in advance now that I make the songs first. Technically, I’m quoting the tradition of music videos but, for me, it’s more of a concept album based on folk tradition, utilizing Ableton Live software and affordable prosumer synthesizers. I’m taking cassette tapes from the 1990s and doing something with them that only these new media can allow me to do, which makes it interesting: I’m reconsidering what folk means now.

Reifying Desire 6, 2014, digital still. Courtesy the artist and Morán Morán, Los Angeles

What does the title of your work Reifying Desire mean to you?

Reifying Desire was an attempt to decipher the schematic diagrams my mother made over the course of 15 years. Sometimes, the drawings are of relatives and sometimes they are of crystalline objects underneath a sentence. It was fascinating to see her use objects to express things that cannot be communicated through basic language. So that became the formal rubric for the animations. I would combine her schematics with somebody else’s language, body or mythology, or my own dance movements, paintings and ideas.

I called it Reifying Desire because I focused on objects of desire that are sometimes indecipherable, because they can’t be described by common language. The title was an oxymoron: the videos never reified anything. The series just kept expanding and evolving.

The harness that you wear in Reifying Desire 6 is studded with smartphone screens playing your videos, like prostheses. Do you believe technology is becoming a bionic extension of the human body?

The harness structure echoes my mother’s drawings, which were always of hybrid objects – like a remote-controlled dick on wheels or a tampon that has battery-pack chargers inside of it. When I wore screens on my crotch, chest and head that were playing the videos, it was like an extension of the virtual in real space. I became a computer-generated character in the flesh. I wanted my body to no longer be human, to become a punctuation mark or some kind of musical note, a kind of pivot that facilitates a narrative.

Alongside more art-historical references, your work also alludes to subcultures like leather fetish and voguing.

Formally speaking, voguing is the only dance style I can use to get my body to form right angles for 2D images that look dynamic in a sequence. I can select and duplicate certain movements to make a perfect triangle, or the angular forms in a Piero della Francesca painting, for example. Voguing is more phenomenological than any other dance style because you are miming a makeup kit, or a lever and a pulley and a hammer.

By appearing in your works, you put your body in a position of vulnerability. When I saw Reifying Desire 6 for the first time, I was struck by the moment where you, the porn-star blogger Antonio Biaggi and your avatars are having sex in a Bodhi-like tree as though you are strange, fornicating fruit. It is very difficult to distinguish in that moment between the sexual and the violent, the sacred and the profane.

I wasn’t trying to be sensational by having sex on camera; every chapter of Reifying Desire is a specific type of gestation cycle. Animation is always about key frames; it’s always about a beginning and an end. I thought it would be funny to close out the gestation cycle in Reifying Desire by getting someone who was known for inseminating other men to have sex with me and produce a kind of binary code. The egg I lay hatches a new human language that metastasizes until it’s out of control.

Lee Edelman’s 2004 book No Future sees queerness as an end – could barebacking, with its transmission of the virus or disavowal of procreation, be interpreted in the same way?

Yes, exactly. I was light-hearted in my decision to cast Antonio and it wasn’t meant to be political, but it ended up coming across that way. The film came out in 2014, which I think was a threshold year for gay sexual politics. Truvada has changed everything. I also wanted to see how sex would be perceived in a CGI film by a public audience. How does that shift in virtual space? Not many people saw it as sex. Some did, but it doesn’t feel like a trigger when you put it in a museum. I’ve seen people take their children around the work unguarded.

Digital animation has enabled you to transform sex not just into a way of transmitting fluids, but a way of transmitting ideas – a kind of body language.

A language, a choreography – a new hybrid form of communication.

Jacolby Satterwhite is an artist based in New York. His work is included in ‘Electronic Superhighway (2016–1966)’ at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, UK, until 15 May. His project, En Plein Air, will premiere at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, USA, in May 2016.