- Source: ARTFORUM

- Author: DEBRA SINGER

- Date: DECEMBER 2007

- Format: PRINT

Best of 2007: On the Ground, New York

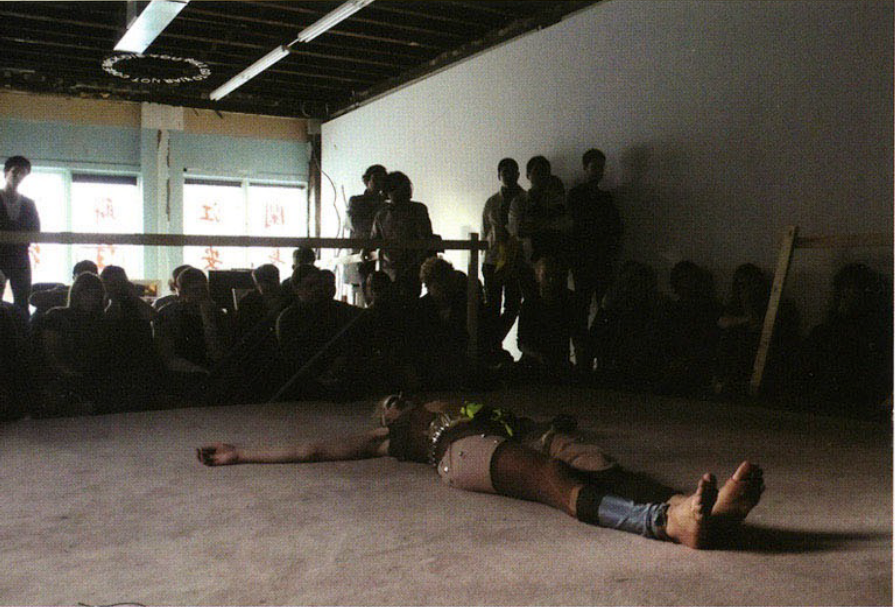

K8 Hardy and Stefan Tcherepnin, Bear Life, 2007. Performance view, Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York, 2007. From Kim Gordon and Jutta Koether, "Dead Already," 2007.

THE NEW YORK STORY may seem to be one of money, but even so, it is a tale encompassing many turns. Certainly, the celestial auction prices of an overheated art market dominated headlines in 2007, to say nothing of griping kaffeeklatsches of collectors, curators, and gallerists. Yet underdiscussed, perhaps, is how the long-bullish economy has affected sectors of the New York art scene that ostensibly linger on its fringes, enabling small galleries and alternative, nonprofit arts spaces to flourish. Indeed, the ever-expanding popularity of contemporary art-underwritten by the city’s many investment bankers, hedge-fund managers, real estate developers, and entrepreneurs, whose pockets have for years been overflowing-has meant that even those galleries cultivating a more renegade, anticommcrcial stance have sold enough to keep the doors open and, on top of that, turn a tidy profit.

Geographically speaking, this dynamic is perhaps nowhere more evident than in the continued burgeoning of the Lower East Side arts scene. While spaces like Participant Inc., Reena Spaulings Fine Art, Orchard, Canada, Rivington Arms, and Miguel Abreu Gallery are still mainstays of the area-to name only a few of the first- and second wave of pioneers to arrive in the neighborhood since 2001 (when it was considered a strange aftershock of the ’80s East Village)-a whole additional slew of modestly scaled commercial venues emerged in the past twelve months, integrating almost invisibly into the still-eclectic grit of Chinatown or else the quickly gentrifying block just north of it. There are, for example, new upstart enterprises like RENTAL-which, as the name suggests, hosts rotating shows by out-of-town galleries-as well as Sunday NYC, Smith-Stewart, and the relocated Luxe Gallery. All of them exude a spunky determination, using every square inch of their barely-bigger-than-a-bread-box spaces to showcase emerging figures; and in an LES context where art venues seem embedded in the comings and goings of ordinary life, it’s an approach that gives welcome relief from the too often monotonous grandeur of that Art Mall to its west. But, of course, one cannot help but wonder how long this environment will last: While existing architectural structures and zoning regulations will forestall any immediate replication of Chelsea in the area, satellite branches of more established enterprises, including Lehmann Maupin Gallery, Salon 94, Freemans, and Eleven Rivington (an outpost of midtown’s Greenberg Van Doren Gallery), are already beginning to appear alongside these galleries’ fledgling efforts. And with the opening of the New Museum on the Bowery this month, the Lower East Side is sure to be fully consecrated as a necessary, no-longer-underground part of the circuit.

This very dynamic, of course, inevitably leads one to consider whether the same economic forces that allowed for such a blossoming of activity have also made it ever more difficult for artists themselves to live and work in the city. For while the Lower East Side is booming not only in art bur in real estate-as was, and continues to be, the case in the transformation of both Williamsburg and Chelsea-the same is true, in a sense, of Bushwick. And there’s the rub: With each passing year, more visual and performing artists are unable to find affordable studio and rehearsal space, regularly getting kicked our of their longtime rentals throughout Brooklyn (to say nothing of Manhattan), clearing the way for upscale condos. In other words, if 2007 was a banner year for the economics of art in New York, it was, unfortunately, a banner year for a kind of exodus as well, with artists no longer just decamping to the next few stops on the L train but, more dramatically, picking up shop and moving upstate, or to Berlin, or to that out-of-town teaching job, or (the best option, in my opinion) to the affordable loft spaces of Philadelphia. This suggests a cautionary tale for our city: Unless something starts to give in 2008, we risk ending up a metropolis filled with art but lacking in artists.

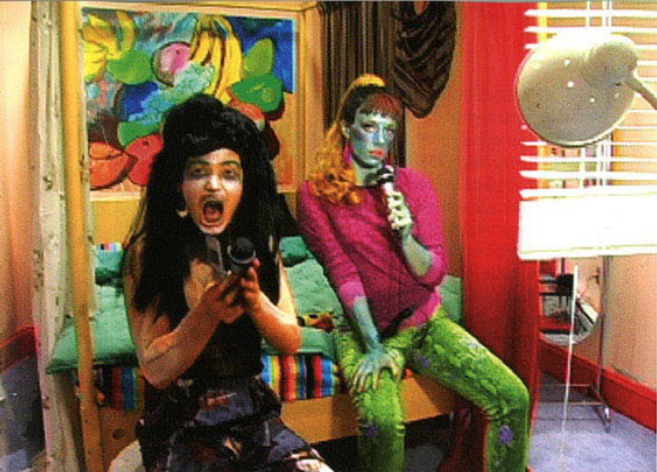

Ryan Trecartin, I-Be Area, 2007, still from a color video, 1 hour and 48 minutes.

In fact, more than one of the year’s highlights in New York came from artists who decided to forgo creative life in Gotham. Ryan Trecartin, for example, did just that, choosing to work in Philadelphia lofts with a tribe of friends and colleagues to produce a distinctive, over-the-top, DIY brand of video making for the YouTube generation. For his September solo show at Elizabeth Dee Gallery, he premiered I-Be Area, 2007, a video filled with a glittery chaos of visual effects and colorful characters-literally, given their dramatically painted faces and creative costuming-and whose elusive, layered narratives touch on themes of identity, ranging from questions of replication and cloning to community and family. (Trecartin’s work, like that of his artistic peers Paper Rad and Kalup Linzy, is both a product and a reflection of Internet and television culture mixed with performance-displaying a low-tech aesthetic of one-stop-shopping video making that is ever more prevalent with today’s democratic ease of digital production. His flamboyant, rough-hewn theatricality, on the other hand, is clearly indebted to the likes of John Waters,Jack Smith, and Kenneth Anger.) And in another of the year’s strongest shows, Michael Rakowitz (a New Yorker recently relocated to Chicago) presented The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist at Lombard-Freid Projects. Using both the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute database and Interpol’s website, Rakowitz has been conducting research on the more than 7,000 archaeological artifacts looted from the National Museum of Iraq in the aftermath of the American invasion in April 2003-making, in turn, paper-mache replicas of the ancient objects out of packaging from Middle Eastern food products and Arabic newspapers. Memorials to history now irretrievably lost, dozens of these objects were exhibited alongside traditional museum labels and accompanying texts derailing information about their origins, the events surrounding the invasion, and the key players at the Baghdad institution.

But most pertinent to an understanding of New York’s rapidly changing cultural landscape might have been, paradoxically enough, a video capturing what is being irreparably lost in another country, on the other side of the world. The subject of a solo show this year at Max Protetch Gallery, Chen Qiulin, a young artist from China, creates performance-based videos that address the psychological consequences of her country’s rapid urbanization-particularly those related to the Three Gorges Dam project, which has resulted in the progressive displacement and relocation of more than a million people. The artist typically recruits a large cast-as is the case with several videos shot in the rubble of the now-demolished village in which she was born-and then often assumes the role of the protagonist in videos centered around theatrical rituals staged in symbolically significant locations. Somehow avoiding the common pitfalls of cloying sentimentality and documentary didacticism, Chen’s best works rather miraculously track the sensibility of a society having to renegotiate its relationship with a rich cultural past in the face of a national identity, cultivated by the government, that is intended to represent modern technological power and corporate grandeur.

Michael Rakowitz, The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist, 2007-, packaging, newspapers, and glue. Installation view, Lombard-Freid Projects, New York.

Chen Qiulin. Garden, 2007, stills from a color video, 14 minutes 45 seconds.

I draw this comparison between Chen’s work and New York because the city’s cultural heritage seems in such dynamic flux, and while the sense of transition here is hardly as extreme as in Chen’s China, it goes without saying that shifting cultural conditions affect production in meaningful ways: Even beyond the question of New York’s affordability for artists, long gone is the time that a smaller scene in the experimental performing and visual arts here allowed for natural dialogue among practitioners from different fields, be they video, music, dance, or theater.

The sheer vastness of the New York context seems to limit this type of conversation, even though performing and visual artists alike would benefit from a broader, more fluid understanding of one another’s issues, accomplishments, and challenges. Indeed, it is a great paradox of the current scene in New York that more interdisciplinary work is being made than ever, yet there is insufficient exchange among artists coming out of distinct traditions-a situation engendering an inadvertent parochialism among artists and audiences alike, and unintentionally reinforcing disciplinary boundaries in turn. The fact is that even if the venues, participants, and audiences for performance-related disciplines might seem to operate in a parallel universe, separate from the art world, there are many shared philosophical and aesthetic concerns that warrant consideration.

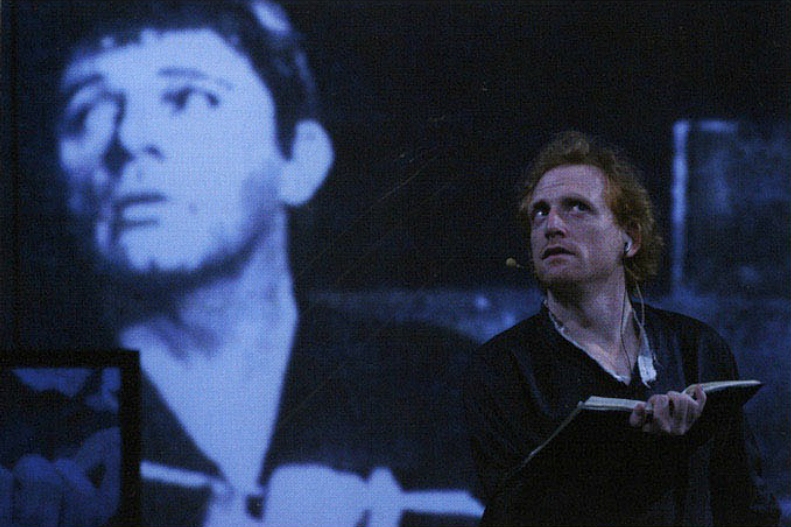

Shakespeare's Hamlet, performed by the Wooster Group in a production directed by Elizabeth LeCompte, 2007. Performance view, Public Theater, New York. Hamlet (Scott Shepherd). Photo: Paula Court.

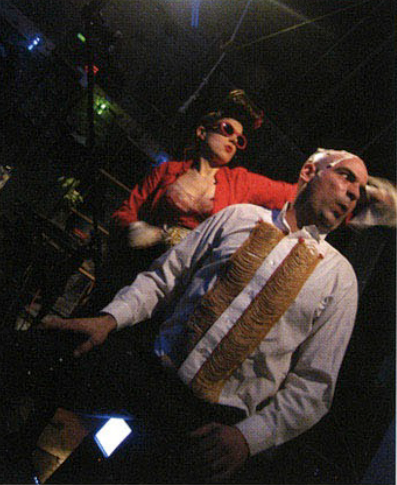

Radiohole, Fluke, 2006. Performance view, Collapsable Hole, Brooklyn, NY, 2007.

For example: Practically everyone in the art world is familiar with the Wooster Group, Richard Foreman’s Ontological-Hysteric Theater, and the Judson Dance Theater, all of which came of age in the more intimate urban settings of the late ’60s and ’70s. Relatively few, however, are aware of the younger figures who have emerged since the ’90s in the wake of these groups, and who are similarly rooted in a cross-section of installation, video, and performance-art traditions in addition to those of theater and dance. The Wooster Group and Richard Foreman, for instance, are the progenitors of such vital theater ensembles as Radiohole and Caden Manson/Big Art Group-both of which, in noteworthy live works made in the past year, wedded a lavish, low-tech, baroque visuality to layered narratives in a manner that immediately brings Trecartin, for one, to mind. Led by Manson (who creates his ensemble works at a place he maintains outside Philadelphia), the Big Art Group often situates closed-circuit cameras amid the action-Manson refers to his performances as “real-rime films”-so that actors appear both onstage and on larger-than-life screens, whether in glamorous close-ups or against faux-scenic backdrops. Exposing the artificiality of the spectacle even while creating it, Manson took up themes of war and trauma in his latest production-a traveling show titled Dead Set #3 (whose New York venue was, full disclosure, The Kitchen)-and, in tragicomic fashion, set them in a campy fusion of club life and pop culture. The mix featured performers shrouded in pink-sequined Abu Ghraib-like hoods; references to television tabloid and news shows, in addition to B horror movies; and borrowed dialogue from online pickup chatrooms.

For its part, Radiohole (a tight-knit ensemble made up of Erin Douglass, Eric Dyer, Scott Halvorsen Gillette, and Maggie Hoffman) generates outrageous productions with riotous displays of props, inexplicably captivating pranks, and perplexing plots inspired by influences ranging from Godzilla movies and spaghetti westerns to Guy Debord. (“Avant-vaudeville mixed with Richard Foreman” is how one friend described their style to me.) Earlier in the year they presented Fluke-an adaptation (of sorts) of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick-in their tiny Williamsburg garage of a space, dubbed the Collapsable Hole. Having crammed the stage with a jury-rigged junkyard set (resourcefully evoking life at sea), the cast painted eyes onto their eyelids in front of a live audience and then performed nearly the entire play with their real eyes closed, mingling the bizarrely awkward body language one might expect with moments of surprising, rehearsed agility-all while viewers were alternately laughing and feeling deep unease at the raucous stunt.

Even the more established theater groups this year warranted consideration in the art-world context, however. Stylishly distilled in its uses of appropriation, simulation, fracturing, and repetition-all strategics deeply familiar to art audiences today-was the Wooster Group’s production of Hamlet with troupe member Scott Shepherd as the lead. Based on the movie version of the Shakespearean play’s 1964 Broadway production, in which Richard Burton played the lead, the Wooster remake brings together live performers onstage and a manipulated “ghost” of the film, which his projected onto the screen behind them. Throughout the show, performers echo aspects of the film, replicating stance, staging, tone, and gesture. The palimpsest of past and present, sound and image, makes it a Hamlet experience like no other, in that the production isn’t about Hamlet at all, but rather about the fleeting uniqueness of live performance and the dominance of our media culture today: The stinging truth of our TiVo times is that greater comfort seems to lie in the distanced repetition of what we already know.

Performance by Bunny love. Bambi the Mermaid, and Eric Schmalenberger in the Annex Room as part of assume vivid astro focus's exhibition "A Very Anxious Feeling." John Connelly Presents, New York, 2007.

It must be said here that Shepherd, with his astonishing charisma and effortless stamina, seems co have single-handedly turned acting into the latest incarnation of virtuosic endurance art. He also starred in the Brooklyn-based ensemble Elevator Repair Service’s production of Gatz, a six-and-a-half-hour tour de force involving (in part) a reading by Shepherd of The Great Gatsby from cover to cover. Due to conflicts with the F. Scott Fitzgerald estate, the production has yet to appear officially in New York, but this year it has traveled around the world (including Philadelphia) to unanimous acclaim. A direct offspring of the Wooster Group in many respects, but with its own distinctive generational qualities, Elevator Repair Service draws inspiration from multiple sources, creating productions as an ensemble, like Radiohole, that are inspired by odd combinations of found text mixed with unusual choreography, low-tech props, imaginative sound tracks, and a wicked dose of whip-smart humor. In Gatz, Shepherd’s character arrives one morning at his shabby, rundown office, where he finds an old copy of the famous novel amid the clutter on his desk and starts to read aloud from it-and then doesn’t stop. Each word of Fitzgerald’s is preserved but also transformed as Shepherd’s coworkers go about their business, ignoring his behavior, until odd coincidences between the book’s plot and the actions onstage start to surface. The results are mesmerizing, being true to the text in a verbatim way but transforming the classic novel-by shifting the context around the reading-into something strange and bewildering even within its own conjured dramatic world.

Bringing such works into art-world situations, and vice versa, and subsequently mingling these various publics would only enrich our understanding of what was perhaps the most pronounced trend within the art world during the past year: the growing presence not only of performance-based video work but also of live performance within alternative contexts, ranging from venues such as Anthology Film Archives, Artists Space, and Participant Inc. to galleries like Greene Naftali Gallery, Elizabeth Dee Gallery, Taxter & Spengemann, John Connelly Presents, Foxy Production, Reena Spaulings Fine Art, Zach Feuer Gallery (LFL), and Miguel Abreu Gallery, among others. The events themselves also tend to take various forms, ranging from simply staged dance performances to live music by local bands to solo theatrical excursions to “performance art” in the more historical sense of the term. Adding to the synergistic spirit is the second rendition of the multi-venue Performa biennial, dedicated to live performance by, or related to, visual artists.

Anthony Coleman performing Robert Ashley's Entrance (1965), Miguel Abreu Gallery, New York, July 26, 2007.

But to consider again the question of New York “on the ground”: That there is such a mélange of activity-each component of which brings its own enthusiastic followers in tow-might also be understood as testifying to a recognized need in New York for more intimate settings of dialogue and exchange. And if so, this desire comes with a certain peril. Without raking a larger cultural context into account, all these activities within the art world risk being put merely in the service of creating distinctive social scenes, galvanizing the energy that live events generate for individualized purposes. Live performance could be so much more than that, even offering a small communal resistance to the totalizing economic forces at play in the city and creating a kind of underground in public.

Oliver Husain, Rushes for Five Hats, 2007. Performance view, Greene Naftali Gallery, New York, 2007. Photo: Sam Pulitzer.