- Source: ASAP Journal

- Author: Alex Pittman

- Date: July 18, 2022

- Format: Online

b.O.s 17.4 / Cotton Ikebana 18??

A prompt, a parameter, a choreography, Black One Shot (b.O.s.) has been our ongoing concentration on the art of blackness. We value the complications, ambiguities, and ambivalences on which the art of blackness thrives. As we’ve said, our physics of black study amplifies the critical resonance of objects (centripetal) over the insistence on what objects must do (centrifugal). X = Object love + art of blackness criticism ≅ disassociate, distend, demand, refract, rejoice. Solve for X in no more than 1000 words.

b.O.s. will run the course of summer 2022 for five consecutive weeks. We invite you to follow and share hard. Thanks to all the contributors and special thanks to Alexandra Kingston-Reese and Wiktoria Tunska.

—Lisa Uddin and Michael Boyce Gillespie (Editors)

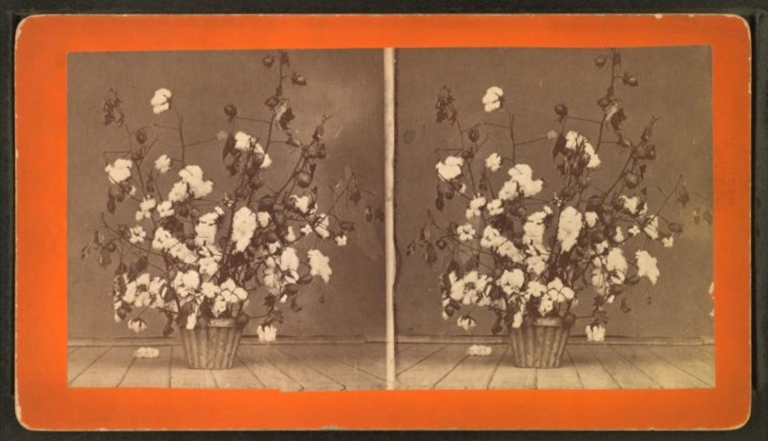

Set against a gray backdrop that occasionally ripples in a breeze, Cauleen Smith’s Cotton Ikebana 18?? (2017) opens with the artist entering the frame from the right to place a white vase on a particle board table before she exits to the left. Reappearing on the right, she sets down a bundle of cotton branches, briefly inspects them, and walks out of the left frame again only to reemerge on the right bearing more. The next time Smith appears, she begins arranging the branches in the vase, pausing here to break off a twig or there to trim a boll. Over the course of nearly seven minutes, this process of entrances and exits, of preparation and positioning that Smith performs briefly and deliberately, plays out as the cotton accumulates in the upper half of the frame. But the viewer does not have long to take in the arrangement after Smith ceases working on it. Instead, a different cotton plant, this one in the form of a 19th century photograph, is slowly superimposed on the screen as Smith introduces a quick cut to a now empty table, with the image’s gradual emergence to the digital surface mimicking the process of exposure in a darkroom. At once flowing and segmented, contemplative and task-oriented, soundtracked by the scraping sounds of its raw material and the ambient noises of its outdoor surroundings, Cotton Ikebana 18?? brings the labor of past and present aesthetic arrangement and image-making to the fore, even as it makes this labor strange. What might Smith’s estrangement of aesthetic labor do as part of a black visual practice, especially in relation to the historical source and medium that her performance references?

The image that fades into Smith’s video is a stereograph produced between 1870 and 1879 by the photographer J.A. Palmer in Aiken, South Carolina. Titled “Cotton Plant,” this artifact consists of two nearly-identical photographs that, when viewed through a stereoscope, creates a single, three-dimensional image. “Cotton Plant” becomes most remarkable when it is viewed within the commercial archive of antiblackness that is Palmer’s series, “Characteristic Southern Scenes.” Advertised as “A Large Stock of Views of Negro Groups, Cabins, Teams, Cotton Fields, and Plants, etc., kept constantly on hand,” the visual and grammatical syntax of Palmer’s stereographic collection suggests a set of equivalences between Black people, architectural features, landscapes, and flora. Arrested with his camera, the relationship between these “elements” is defined by their givenness (“kept constantly on hand”) to de-animation, extraction, and reanimation through the image-making and viewing process.

As Leon Gurevitch observes, stereoscopy—the technique of producing depth and movement from a flat, static surface—was a commercially popular form in the 19th century that was instrumental in producing imperial commonsense. Referring to how stereoscopy simultaneously reminded viewers of the body’s role in perception and ordered information about the world according to colonial categories, Gurevitch argues that the pleasures of remote control that these handheld viewing devices offered imperial spectators also anticipated the 21stcentury’s new media cultures.(1) Palmer’s “Characteristic Southern Scenes” suggests that this stereoscopic fantasy depended on severing the link between the recently abolished institution of slavery and the regimes of coerced labor that are its afterlife. Indeed, to advertise Aiken, South Carolina, as a winter destination, Palmer’s stereographic series renders Black sharecroppers as visual commodities, liberated from bondage and free to circulate as inert curiosities to bourgeois travelers in the wake of the Civil War.

Smith’s embodied citation of “Cotton Plant” is exemplary of the careful, creative ways she engages with the violent legacies of visual technologies and image-making processes throughout her work. Elsewhere, she has referred to the colonial and anthropological function of stereographs and raised the question of how to use this imagery as a device against its imperial function.(2) In other words, how might this device be used to create what Tina Campt identifies as “a black gaze,” that is, a practice of tarrying with uncomfortable visual archives that open “new ways of encountering the precarity of Black life” apart from those visual logics that position blackness only in a subordinate relation to whiteness.(3) As a subset of her broader visual practice, Smith’s ikebana videos are especially fruitful sites for considering the maintenance of a black gaze in its fundamental ambivalence. Staged in relation to antiblack institutions like the prison and the plantation, works such as Cotton Ikebana 18?? and Orange Jumpsuit, insinuate loitering, meditative practices into places designed for extraction and enclosure.(4) Where these institutions produce and exploit “densely connected social separateness” as racial capitalism’s geographical and phenomenological expression, Smith’s floral arrangements cultivate an archive of divergent labor.(5)

On Instagram, Smith frames Cotton Ikebana 18?? within the historical-political consciousness of everyday life in 2020. Here, against the logic of enclosure, she speaks of wondering at the blooming cotton while driving along the I-5 in California while she meditates on the competing promises and truth claims of mainstream political parties in the United States. But what strikes me in her captioning of this work is how she claims a space of freedom to contemplate (both to wonder and wander) in the shadow of histories of exploitation without assuming a relationship of identity with them. As she writes, “America’s economic power was founded on King Cotton. The north has the mills, the South had the raw (really really raw) materials. Cotton has enthralled this country for centuries. It captivated my attention today. … No fingers will bleed in the harvest. Yeah good.” Smith’s estrangement of aesthetic labor is especially pertinent here for a black gaze against a visual archive like Palmer’s. Where both cotton plants and Black people appear as de-animated objects for the visual pleasures of northern industrialists, Smith brings an insubordinate living labor to the processes of aesthetic arrangement and image-making. Hers is a non-extractive practice that is maladjusted to but not forgetful of racial capitalism’s visual technologies and the forms of severance they impose.(6)

- Leon Gurevitch, “The Birth of a Stereoscopic Nation: Hollywood, Digital Empire, and the Cybernetic Attraction,” Animation: An Interdisciplinary Journal 7.3 (2012): 244.

- Cauleen Smith, “‘Pilgrim’ and ‘Crow Requiem’: Screening and Talk with filmmaker Cauleen Smith and Tina Campt,” Barnard Center for Research on Women’s 46th Annual Scholar and the Feminist conference, New York, NY, March 15-April 9, 2021. Available online at www.youtube.com.

- Tina Campt, A Black Gaze (MIT Press: Cambridge, 2021), 8, 17.

- In Orange Jumpsuit (2019), Smith arranges orange flowers that resemble the shade of prison-assigned jumpsuits before leaving them outside of a detention center, where the arrangement is picked up by an anonymous person who might or might not be visiting the prison. Where Cotton Ikebana 18?? brings processes of aesthetic labor to the fore, Smith’s ikebana practices in Orange Jumpsuit appear more attuned to the politics of sartorial visibility within, as well as the possibilities of gifting that can subsist nearby, the carceral system. In an interview with Fanta Sylla published by Flash Art, Smith describes her use of the traditional Japanese art of ikebana in terms of her interest in how humans project meaning into nature in an attempt to control it. Reading this statement in light of the racial capitalist institutional settings that often frame these ikebana practices, this subset of works could be productively understood in terms of Lisa Lowe’s use of “intimacy” as an analytic for tracking the voided historical relationships between slavery, settler colonialism, immigrant labor, and liberalism. In particular, Lowe’s use of intimacy to refer to the challenge of writing subaltern history in light of the repressed spatial proximities between enslaved, immigrant, and native peoples might be understood in line with Smith’s practical commitment to drawing links between places and legacies (like the plantation and the prison) that are often denied. Lowe’s historiographical study and Smith’s black radical artistic project are united in their commitment to a simultaneously grounded and speculative practice of drawing connections across spaces of normative forgetting. See Lisa Lowe, The Intimacies of Four Continents (Duke University Press: Durham, 2015).

- Jodi Melamed, “Racial Capitalism,” Critical Ethnic Studies 1.1 (Spring 2015): 81.

- Maladjusted is a reference to Smith’s essay, “The Association for the Advancement of Cinematic Creative Maladjustment: A Manifesto,” Black Camera 11.2 (Spring 2020): 246-255.