- Source: THE ART NEWSPAPER

- Author: Cristina Ruiz

- Date: NOVEMBER 2014

- Format: PRINT

Artist interview: Ryan Trecartin, LONG DARK NIGHT OF THE SOUL

Shooting after hours contributes to the hallucinatory feel of Ryan Trecartin's dizzying films.

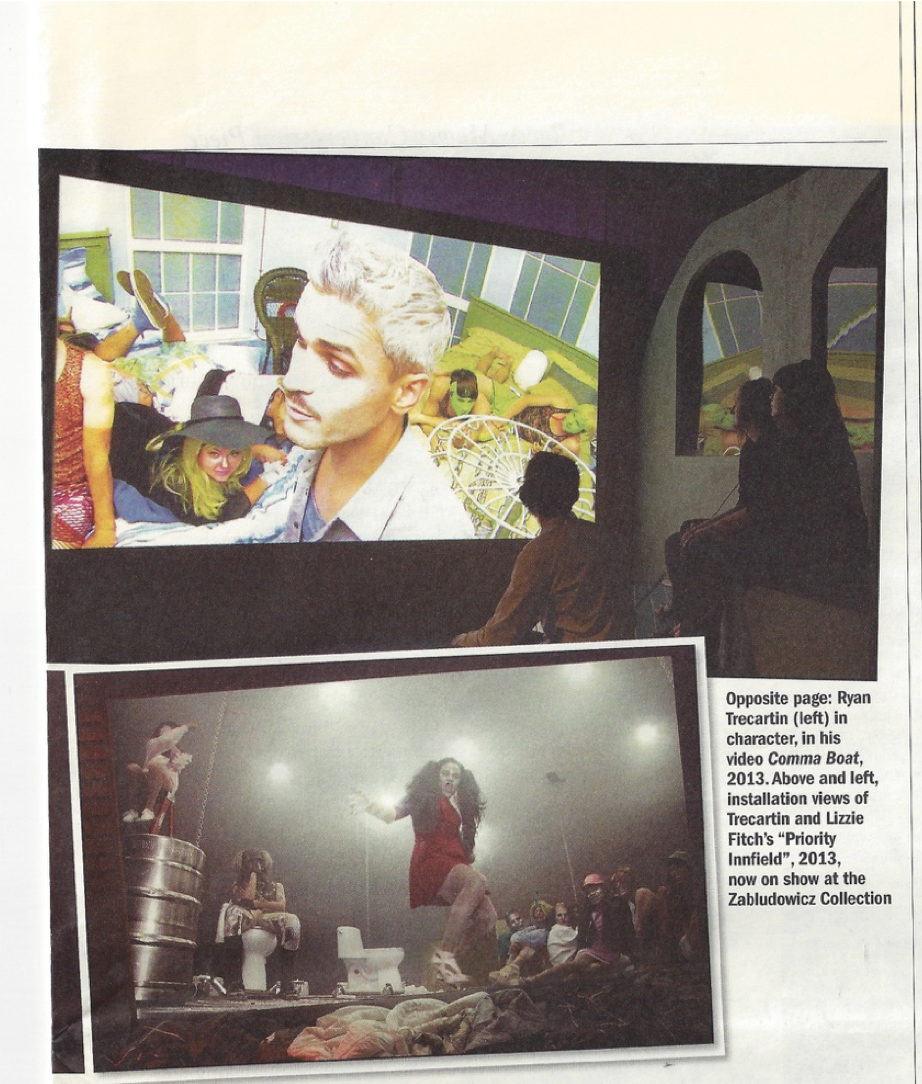

The internet and the cultural innovations it has introduced are changing the ways in which we speak, act and relate to one another – but advances in technology are outpacing our ability to understand them. These, broadly, are the underlying themes of Ryan Trecartin’s films, which are made in collaboration with fellow US artist Lizzie Fitch. The fast-paced editing, hallucinatory animations, loud soundtracks and characters’ disjointed speech and actions merge to create portraits of the YouTube generation that are at once exciting, disturbing and alienating assaults on our senses. Four of the duo’s films made waves at the Venice Biennale in 2013. Now they are on show at the Zabludowicz Collection in north London, in the artists’ first show in Britain. We spoke to Trecartin just after it opened.

The Art Newspaper: Your installations seemed designed to induce total surrender in the viewer. Is that their purpose?

Ryan Trecartin: I definitely think of them as providing an experience that, at first, functions similarly to a ride and almost uses the language of a theme park or a natural history museum. The movies are intended to be entertaining, but this is always merged with the ideas that drive the material and the conceptual basis for the work. I hope that, after surrendering to the experience, there’s a process of reading the work that can happen over multiple viewings. I think of them as something that gets read rather than just watched.

There is a hallucinatory, nightmarish quality to your films. You examine the way technology is changing our behavior, language and relationships. Is there an element of warning built into that?

One of the reasons I work with the movie form is that you can suspend multiple intentions or strains of thought within the same work. Sometimes it’s just about exploring and revealing things, and trying to show a reflection of something that enables you to see it in a more raw way than how you experience it in real life, where you’re possibly desensitized to it. I don’t necessarily think of warnings, I think that everything is potentially positive and exciting, and it’s just about how technology gets used. The works perhaps seem nightmarish because the darker side of things is a symptom of really exciting, creative changes in the world. Destruction, perversity and dysfunction can ultimately allow for movement and for states of being to evolve.

But some of the people and situations are really menacing.

The characters sometimes perform cruel actions that would mean something very different if you were in a virtual state where getting rid of someone doesn’t mean you’re actually getting rid of them.

Like a video game?

Yes. So an action can mean many different things. I think that certain topics are really scary in one context and then potentially playful, creative and inventive in another context, so I like to show that. Then I complicate the context it’s actually happening in, so that it remains unclear.

A lot of your work seems to focus on today’s self-publicizing, narcissistic, reality-TV youth culture. How do you think your work will evolve as you get older?

It’s evolved a lot since the first movies. People associate the way in which language is evolving with youth culture, and for a long time that was the place where it was acceptable to butcher and invent language. But if you really listen to people of all ages, you can hear that this extends to all of us. We’re staying younger and younger as a species – not just physically, but also in our mindset. Culture is not something that is just handed down to people any more; we’re all making it together, and this has a profound effect on language. Technology also accelerates the way in which language is changing. I like to take things that people see as “tween” and put them in more adult and more destructive, friction-filled settings, and draw attention to the fact that youth is no longer related to the number of years lived.

You don’t speak like the characters in your films, though.

The characters exaggerate, extend and manipulate these changes in language. The movies are not documentaries – in other words, unmediated versions of real life. I have lots of different ways of behaving or speaking in different situations. This is a formal situation – an interview – and it differs from the way I talk when context shifts. People have multiple ways of behaving rather than static states of being that they maintain consistently; it’s like accents and way of exchanging language that are no longer tied to specific cultures or places. The internet has given everyone a bird’s-eye view of the world.

It must be easier for younger viewers to understand y0ur work, compared with older ones who are less familiar with new technology.

I feel as though it’s more of a state of mind. There are older people I know who are really quick to understand how things are changing and evolving, just as much as younger people. People who are raised with access to the internet, movies, reality TV and the news are obviously able to understand certain things in my work that those who weren’t around [those media] will never understand in the same way. At the root of the movies, though, are basic issues about humanity and relationships that anyone can understand.

There are narrative snippets in your work, but never enough to construct a coherent story. Is that intentional?

I do think of the movies as stories. Although they have a non-linear feeling, there’s actually a mesh of many different linearities that don’t necessarily function in complementary directions. I don’t try to hide information from the story, but I like showing the secondary information around it. So in Center Jenny [2013], which is about an educational system where people are learning about their ancestors through misguided forms of sorority culture, there’s a character named Sara Source who brags about how super-privileged she is, and how her family funded a war. So there’s this big, upsetting idea that never gets developed, and it’s clearly part of the plot, although it’s mostly used to shine light on less important things. It doesn’t get resolved in any way that’s going to feel satisfying. She also tells us that her vacations involve dropping canned food on poor people. If I were to make a mainstream movie – and I definitely want to make some in the future – that idea would be developed a lot more directly. But I don’t feel that that’s what this work is about right now. Articulating the nuances around the reflections of larger plot ideas sometimes has more impact than just following the larger plot idea exclusively.

Your characters often speak in banalities – a lot of them very funny – and then they’ll suddenly say something profound.

It’s really important to have the more profound moments surrounded by entertainment. That’s a reflection of the world we live in, and it’s also how I like to receive information. Humour can be a great delivery system for complicated ideas.

Do you write all the dialogue? Do actors improvise?

An early work like A Family Finds Entertainment [2004] was almost entirely scripted, as was I-Be Area [2007], but by the time I made the “Any-Ever” movies [2009-11], I was working with friends with whom I had worked quite a few times, so there was a lot more collaboration. I was still shooting in the way I used to, where I would have a scripted line and would feed it to the actor, along with direction about performing an action or inhabiting a particular vibe. No one would see the script. I like it when performers don’t know where a story is coming from or where it’s going, so there’s a certain open-mindedness to what they’re saying. People can’t act in the traditional sense because they don’t know what the wider story is, and that naivety can make a sentence more transcendent. Actors bring their own interpretations and associations to fill in the “blanks”; you can’t feed someone that, because what they add to the sentence is better than anything I could give them. A lot of improvisation happens because an actor will hear the sentence incorrectly, and their “misunderstanding” transforms it into something much more interesting. And then I respond, which takes us even further off the script, but what ensues is a real-time process of call and response. Lately, I’ve been expanding that process by feeding performers long paragraphs and asking them to interpret what they think I said.

So they would never go away with a script and learn their lines?

No. If I think a line is essential the way it’s written, I’ll just keep feeding it to them until they say it. If the line is more of an idea, or a topic I’d like to cover, we’ll keep filming it until I feel that I’ve got an inspired version of it. So there’s a lot of improvisation, but it all starts from the script.

And a typical shoot will last one day?

It’s one day, but we usually start around 4pm or 5pm and end at 8am. We always film at night, so our shoots are really, really long. We usually start off getting really good footage, and then things often take a turn and the shoots get a little wack for a while. But then it takes another turn for the better once people start getting tired and weirdly poetic; those last four hours of a shoot are usually really special. When the sun’s about to rise, people get that crazy sleep-awake feeling.

There’s so much in your work that the viewer almost needs to watch a film and then process it before coming back to it.

The plots have spaces in them that are meant to merge with memory or lived experience. Ideas congeal or start to coalesce during time away. There’s a process of mingling them with your own associations that needs to happen, and that process is important for picking up a work and leaving it and picking it up again. It’s a bit like reading, in that way. I hope that the movies can be experienced through different framing devices, and that brings out different aspects of the content. When people watch them on Vimeo, where they can stop and start them whenever they want, that brings out different content then if they see them in a cinema, where you’re thinking of things as scenes in a cinematic narrative that moves from A to B – or in an exhibition space, where it’s much more game-like, where you’re navigating the space and going in and out as you want.