- Source: ARTSY

- Author: AYANNA DOZIER

- Date: OCTOBER 18, 2022

- Format: ONLINE

Across Figurative Works, Black Artists Use Self-Expression to Redress British Colonialism

Anya Paintsil

Blod, 2022

Art for Black Lives

During an 1986 interview with scholar and artist Coco Fusco, legendary Black British artist-filmmaker Judah (née Martina) Attille stated that British arts and media is informed by Eurocentric ideas that negate and belittle its own role in colonization. In particular, she drew attention to the dry, mainstream politics that Black British artists are expected to internalize and reproduce across their work—thus leaving Black art and film to resolve and redress numerous falsehoods about their histories and lived experiences, which, critically, leaves no room for pleasure.

New generations of artists are creating enriching political arguments to change notions of empire and British colonialism while integrating self-expression. In honor of Black History Month in the U.K., Artsy is partnering with Art for Black Lives to offer a collection of limited-edition prints by eight of these artists, including Shannon Bono, Cece Philips, Emma Prempeh, Alfie Kungu (who identifies as a person of color), Tunji Adeniyi-Jones, Anya Paintsil, and the artistic duo of Stella Murphy and Olivia Sterling. All proceeds from the sale, which continues through December 7th, will go towards Black Trans Alliance—a Black-, queer-, and trans-led nonprofit organization that protects and amplifies the voices of Black trans folks in London and beyond.

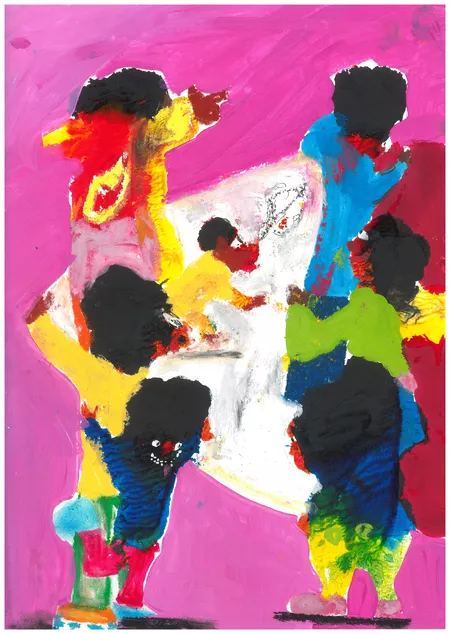

Alfie Kungu

Party, Party, 2022

Art for Black Lives

Emma Prempeh

Red, White, Blue and Brown, 2022

Art for Black Lives

Featuring a range of figurative styles, the prints deliver a sample of the narrative-oriented approaches emerging out of the Black British arts scene. In Prempeh’s Red, White, Blue, and Brown (2022), we see a woman sitting on the floor with a glass in one hand, raising it mid-air as if for a toast. She casts her head back to the viewer, brimming with a smile. In front of her lies an old-school vinyl record player system with speakers. The original painting’s brushstrokes create a hazy filter over the image that still shines in the print, placing it somewhere between personal memory and a Polaroid photograph. Red, White, Blue, and Brown is a glimpse into a private life that reveals Black British experiences beyond institutional narratives to deliver a sense of daily pleasure.

For a U.S. audience, institutional racism abroad may be less known or understood. Artsy spoke with British curator and scholar Cheraine Donalea Scott to gain insight into the state of Black British art in relation to contemporary culture and politics in the U.K. According to Scott, part of the problem is the art world’s lack of transparency, which makes it difficult for cultural producers of color to gain access and make a sincere impact to help others.

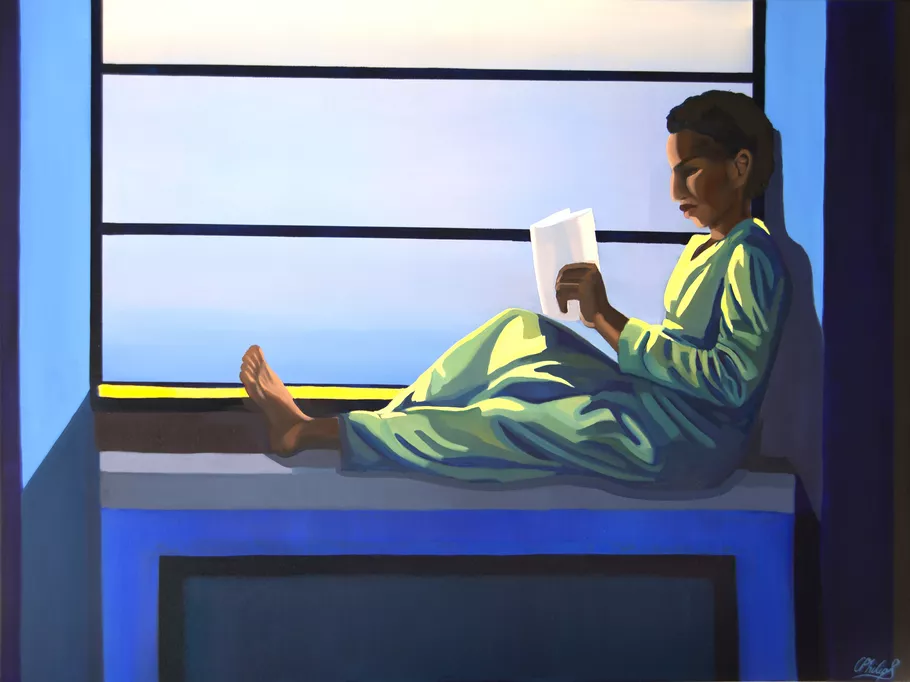

Cece Philips

Mood Violet, 2022

Art for Black Lives

Curated efforts that emphasize the specificity of Black British art help demystify these narratives. “The art institutions in the U.K. have a serious race problem both on an institutional level and in the art [that is] collected,” Scott said. “There are not enough Black people sitting on boards of trustees, working in collections, curation, etc., and that gets shown in their programming. Black British artistic talent goes underrepresented in these spaces, especially young or early-career Black artists whom these spaces can be abusive towards.”

Adeniyi-Jones’s lived experiences reflect the lack of institutional reconciliation for Black artists in the U.K. The main reason he left London for the U.S. was to have greater access to opportunities; however, he noted that the Black British arts scene has been gaining more recognition in recent years. “I believe that things have significantly improved since I made that move in 2015. We are seeing the U.K.’s top art programs, both on a student and faculty level, making encouraging changes,” Adeniyi-Jones said, citing Alexandria Smith’s appointment as head of painting at the Royal College of Art in 2019 as an example.

Tunji Adeniyi-Jones

Poetic Feet, 2022

Art for Black Lives

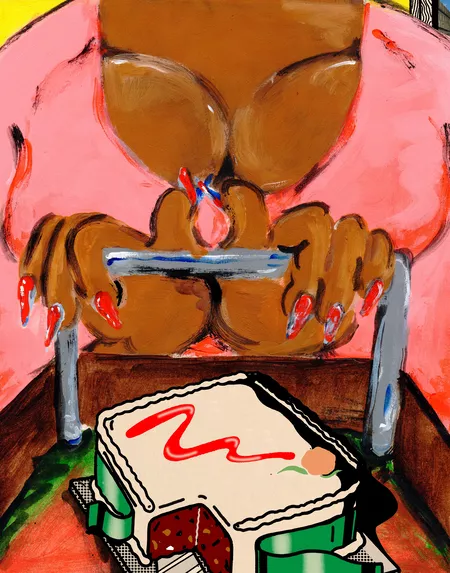

Stella Murphy, Olivia Sterling

Happy Rum Cake, 2022

Art for Black Lives

Though not rooted in a brick-and-mortar gallery or a museum space, online exhibitions can redirect a global audience’s attention towards this dearth of Black British visibility while providing opportunities for artists to share their work with others. For Murphy, the print sale was an opportunity for her to collaborate with Sterling to create a visually dynamic work that spotlights the contributions of Black British women artists in the realm of graphic design and comic books.

“The U.K. has an amazing back catalogue of talent and invention in terms of comic art,” Murphy said. “Some of the most relevant and continually exciting sources of inspiration for me are the psychedelic era of the underground British press in the 1970s, such as Oz magazine and the artwork surrounding CB Radio Culture. Unfortunately, I don’t see myself reflected in most of these artists and I would say that it is still a largely white male-dominated scene today, which I hope will change in the future.”

Murphy and Sterling’s deliciously vibrant print Happy Rum Cake (2022) blends Sterling’s painterly style with Murphy’s dynamically punchy-graphics to create a sumptuous image. Depicting a woman from the neck down hovering above a cake, the image evokes tensions and serious arguments about the hypersexualization of curvaceous Black women, while, at the same time, making room for food and bodily pleasures to be centered without shame.

Shannon Bono

Opposing Forces, 2022

Art for Black Lives

Meanwhile, Bono’s print Opposing Forces (2022) features a woman gazing upon two African sculptures. Her work emphasizes how Black womanhood is shaped by and in dialogue with African and Christian iconography across the diaspora. “I use the body as a powerful signifier that can provoke dialogue and I am exploring magic from an African perspective,” Bono said. “My practice is always evolving and I have been incorporating more still life within my current series, but the core themes [of Black womanhood] within the work remains.”

Both Bono and Murphy note the shifting landscape and support for Black British artists, and hope that it creates legitimate change with a lasting impact. “Being part of this Artsy [and Art for Black Lives sale] is a great opportunity to provide support to an overlooked community of people and gives a platform to artists of color discussing important issues within their practice,” Bono said.

Critically, the artists emphasize the value of personal support; the pursuit of self-expression is needed to coexist with institutional change. As Murphy concluded, “Emotional support as well as financial [support] is vital, and I’m really happy to donate work to raise funds which go towards putting these measures in place.”