- Source: Interview Magazine

- Author: Kat Herriman

- Date: November 23, 2020

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

A Meditation on Manhattan

in the Work of Torey Thornton

If you need proof that New York isn’t dead, look no further than Torey Thornton. The Big Rotten Apple plays a critical, pronounced role in the work of the 30-year-old artist, whose bold, auto-fictive practice traverses mediums (painting, sculpture, and video) and modalities (diaristic, absurdist, and minimalistic) to shine a light on the tension between identity and projected identity—whether it’s of the self, a community, or an entire city. “New York has raised me in so many ways,” says Thornton, who moved to Manhattan from rural Georgia in 2008 to attend Cooper Union. “The opportunity to brush against experiences here, it’s all research that informs the work. New York reminds me so much of the complexities and nuances of life.” Like New York, what Thornton makes defies characterization. At the 2017 Whitney Biennial, they presented a large circular-saw blade bejeweled with found painted rocks, and titled it “Painting”— sidestepping that market-leading medium, and pushing against the fetish to classify artists. In their 2019 solo show at New York’s Essex Street, Thornton turned the gallery into a meditation garden littered with urban cast-offs: Crocs, gourds, plastic magazine racks, and Croakies cables. If the audience expected clear-cut answers, or the artist to riddle out a meaning, they were presented instead with a mysterious sense of the disparate and unresolved. Taken in its entirety, the arrangement of materials created a haunting portrait of all the rote, everyday routines of city dwellers: getting dressed, commuting to and from work, getting undressed.

This winter, the Brooklyn-based artist returns to Essex Street with an exhibition of pieces they started before the pandemic, but whose gestures and considerations were amplified by the global emergency. “COVID highlighted concerns that have been quietly present and looming over me my whole adult life,” they explain. “It has exposed the weak points on top of which we’ve been building for years with faux dreams and false freedoms cloaked in holographic, sugar-coated capital. What COVID has done is show me who and what’s most important to me now. Who knows what tomorrow brings.”

“How Many Ways to Understand Moving Image, How Many for Vanity,” 2018. Photographed by Lance Brewer, courtesy the artist and Essex Street / Maxwell Graham, New York.

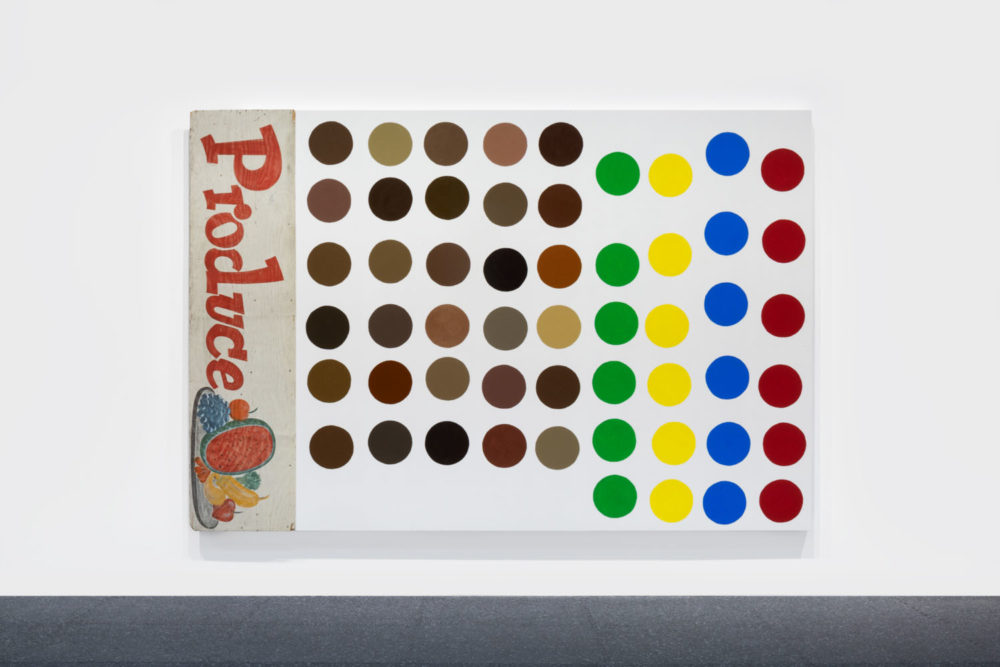

“(How literal you want me? Dirt’s foundational and socially homogeneous overlap, which mirrors all skins, sampled, which also appear as topographical tea perspectives, with Twister as a social teacher and presenter of various discomforts depending your space) (e.g.: my one hyper key as appetizer),” 2019. Courtesy the artist and Morán Morán, Los Angeles.

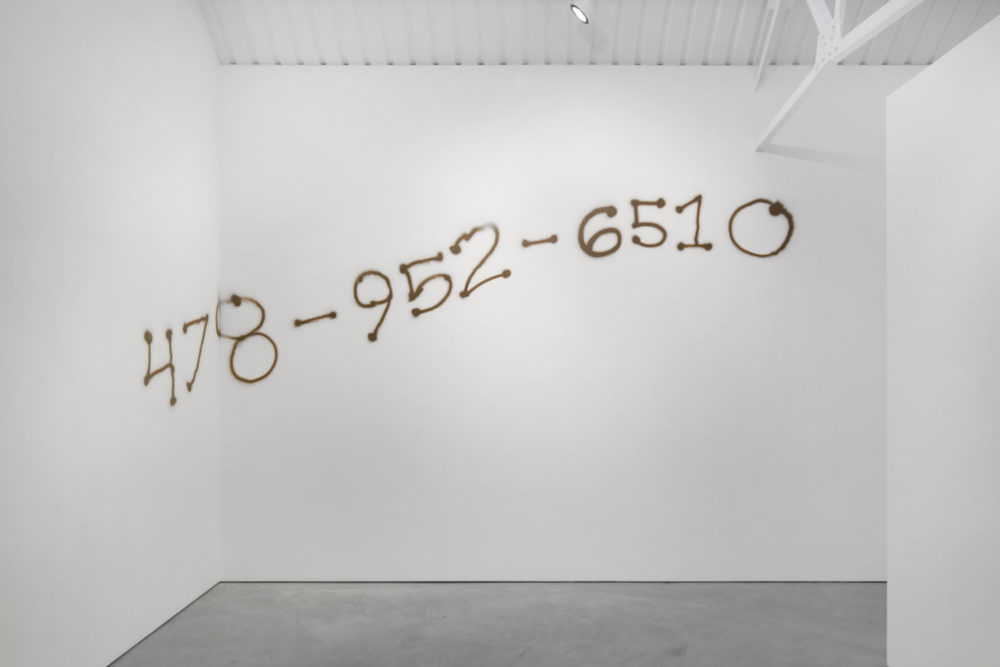

“A Height’s Presence in Isolating, Who’s Do You Put Yourself in and Why (Olive New York Crazy City) (right),” 2019. Courtesy the artist and Essex Street / Maxwell Graham, New York.

“Labor Cont(r)act (1),” 2019. Photographed by Benjamin Westoby, courtesy Modern Art, London.

“Whose Authorship in Living Denied Expression,” 2019. Photographed by Benjamin Westoby, courtesy the artist and Modern Art, London.

“What Is Sexuality, Is the Scale Infinite Similar to a Line,” 2017. Courtesy the artist and Essex Street / Maxwell Graham, New York; Morán Morán, Los Angeles; and Modern Art, London.

This article appears in the Winter 2020 issue of Interview Magazine. Photography Randy Singleton