- Source: OCULA

- Author: Misong Kim and Mathias Agbo Jr

- Date: JUNE 13, 2023

- Format: DIGITAL

Jareh Das on the China-Africa artistic exchange

Jareh Das. Courtesy Jareh Das.

When Jareh Das visited Hong Kong more than a decade ago, she noted ‘there was no visible presence of Black artists across the city’. Since then, there has been a marked increase of African and African diasporic artistic presence in both Hong Kong and mainland China.

Last month John Akomfrah’s first solo exhibition in China opened at Lisson Gallery’s Beijing outpost, while White Cube Hong Kong recently presented Deep Dive (22 March–20 May 2023), a solo show of British-Nigerian artist Tunji Adeniyi-Jones. At this year’s Art Basel Hong Kong, Jareh Das moderated the panel discussion, ‘Locating the Continent: Representations of/from Africa in Hong Kong’.

Dr Jareh Das is an independent curator, writer, and researcher based in West Africa and the U.K. In 2022, she curated Body Vessel Clay, a 70-year survey of Black women artists working in clay at Two Temple Place, London. Das was the inaugural recipient of an Early Career Fellowship from the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art in 2022, a two-year fellowship that will enable her to further her research in postcolonial Nigerian and British studio pottery.

Exhibition view: Body Vessel Clay: Black Women, Ceramics & Contemporary Art, Two Temple Place, London (29 January–24 April 2022). Courtesy © Two Temple Place. Photo: Amit Lennon.

In her appraisal of the latest edition of Art Basel Hong Kong, Das noted that ‘across generations of African artists, momentum is building to establish a global profile while intentionally staying on the continent to contribute to art ecosystems there and encourage local, cross-continental, and international exchanges.’

These international exchanges continue in the form of Das’ exhibition in Shanghai. Her first curatorial project in mainland China—a two-part exhibition titled PUBLIC PRIVATE at Pond Society, Shanghai (10 June–20 July; 29 July–7 September 2023)—brings together 12 contemporary painters from Africa, Asia, the U.S., and U.K.

Left to right: Anthony Cudahy, projection/riven (2023). Oil on canvas (diptych); Caroline Walker, Study for Disturbed (2017). Oil on paper. Exhibition view: Group exhibition, PUBLIC PRIVATE – Part 1, Pond Society, Shanghai (10 June–20 July 2023). Courtesy © Pond Society. Photo: Hong Zhang.

Artists including Tunji Adeniyi-Jones, Anthony Cudahy, Ulala Imai, GaHee Park, Sarah Slappey, and Michaela Yearwood-Dan present new, transnational approaches to figurative and landscape genre painting from the vantage point of their respective locations.

In the conversation that follows, Das speaks with Nigerian designer and built environment researcher Mathias Agbo Jr on the entwinement of China-Africa relations with African artists’ visibility in the global art scene, and what we can expect to see in the exhibition at Pond Society.

Wallen Mapondera, Kumba Kwababa Vangu II (2023) (detail). Cardboard boxes, waxed thread, and packaging tape on canvas. 184 x 379 x 8 cm. © Wallen Mapondera. Courtesy SMAC Gallery.

MAJ: You recently spent some time in Hong Kong in March and April, covering African artists and artists of African descent at Art Basel. How did that go?

Wallen Mapondera, Kumba Kwababa Vangu II (2023). Cardboard boxes, waxed thread, and packaging tape on canvas. 184 x 379 x 8 cm. © Wallen Mapondera. Courtesy SMAC Gallery.

Left to right: Sarah Slappey, Slip and Fall (2023). Oil and acrylic on canvas; Hyegyeong Choi, Prickly Women (2023). Acrylic on canvas; Dominic Chambers, Warm Morning (2023). Oil on linen. Exhibition view: Group exhibition, PUBLIC PRIVATE – Part 1, Pond Society, Shanghai (10 June–20 July 2023). Courtesy © Pond Society. Photo: Hong Zhang.

The panellists also discussed what it meant for contemporary African artists to contribute to changing views and reconsiderations of stereotypes. Given that misconceptions about Africa’s cultural contributions persist, they sought to reveal the nuances of African art and cultural production in general.

Gauging from conversations I have had with artists and their galleries, the experience was very positive. Sales were encouraging and the potential for developing future projects in Hong Kong and China were spoken of with great enthusiasm. The inclusion of African artists at different stages of their careers for me signalled progress since my last visit to Hong Kong. It certainly feels like there are future exchanges that will lead to more visibility for African artists in China in the years to come.

Exhibition view: Art Basel Hong Kong (23–25 March 2023). Courtesy Art Basel.

Left to right: Tunji Adeniyi-Jones, Triple Dive Red II (2023). Oil on canvas; Sarah Slappey, Slip and Fall (2023). Oil and acrylic on canvas. Exhibition view: Group exhibition, PUBLIC PRIVATE – Part 1, Pond Society, Shanghai (10 June–20 July 2023). Courtesy © Pond Society. Photo: Hong Zhang.

We will begin to see more of an integration of these China-Africa relations in the arts through more exchanges and visibility across both continents—evident in ABHK’s spotlight on African artists this year. The last Dakar Biennale, Dak’Art 2022, also featured a China Pavilion for the first time, presenting 12 Chinese artists in African’s longest-running biennial.

There need to be more exchanges to fully assess the perception of African art and artists in China, but there is no denying the complicated geopolitical dynamics between the two—particularly in relation to criticism of African nations entering a ‘debt trap’ due to vast loans from China.

The influx of Chinese imported goods in Africa has also raised concerns around the continent, since they undercut local manufactured products and crush local businesses. China-Africa relations in contemporary art is something that independent curator Lou Mo has analysed in great depth in her 2022 paper, ‘Triangulating Africa: Contemporary art as a terrain for creating China-Africa connections’.

Exhibition view: Tunji Adeniyi-Jones, Deep Dive, White Cube, Hong Kong (22 March–20 May 2023). Courtesy White Cube.

MAJ: How has the work of contemporary African artists been received in China? Do Chinese audiences consider this genre ‘African’ enough, in comparison to traditional African art?

JD: It is an exciting moment for intercultural exchange between these two continents, particularly with how much openness and development we’ve seen in the demand for collecting contemporary African art globally—not just in China. Public and private collections continue to probe and address gaps in art history, with a move towards transnational models for art that are more inclusive and representative of global art movements.

‘African artists, like artists everywhere else, continue to challenge the limitations of how they are framed. What makes African art African? This is almost impossible to answer.’

There is a lot of interest in contemporary African art—Chinese audiences are genuinely curious about the social, cultural, and historical influences informing African artists and the work they are making.

Left to right: Tunji Adeniyi-Jones, Triple Dive Red II (2023). Oil on canvas; Sarah Slappey, Slip and Fall (2023). Oil and acrylic on canvas; Hyegyeong Choi, Prickly Women (2023). Acrylic on canvas. Exhibition view: Group exhibition, PUBLIC PRIVATE – Part 1, Pond Society, Shanghai (10 June–20 July 2023). Courtesy © Pond Society. Photo: Hong Zhang.

The question of whether art by African and African diaspora artists is ‘African’ enough is a bit redundant in my view. Artists continue to respond to and reflect on the conditions that inform their work, which are as nuanced and diverse as the many individuals from so many different locations on the continent and beyond.

African artists, like artists everywhere else, continue to challenge the limitations of how they are framed. What makes African art African? This is almost impossible to answer—Africa is many things to many people. It is full of pluralities as well as contradictions.

Sarah Lee, Radiance (2023). Oil on canvas. 152.4 x 177.8 cm. Courtesy the artist and Anat Ebgi.

MAJ: You are presently in Shanghai to curate an exhibition centred on contemporary painters. Tell me more about this—what artists will be on view?

JD: This is my first curatorial project in mainland China, at Pond Society in Shanghai. Titled PUBLIC PRIVATE, the exhibition will take place between June and September this year and surveys an intergeneration of 12 contemporary painters, with new and recent works by Tunji Adeniyi-Jones, Hayley Barker, Dominic Chambers, Hyegyeong Choi, Anthony Cudahy, Ulala Imai, Sarah Lee, Jonny Negron, GaHee Park, Sarah Slappey, Caroline Walker, and Michaela Yearwood-Dan.

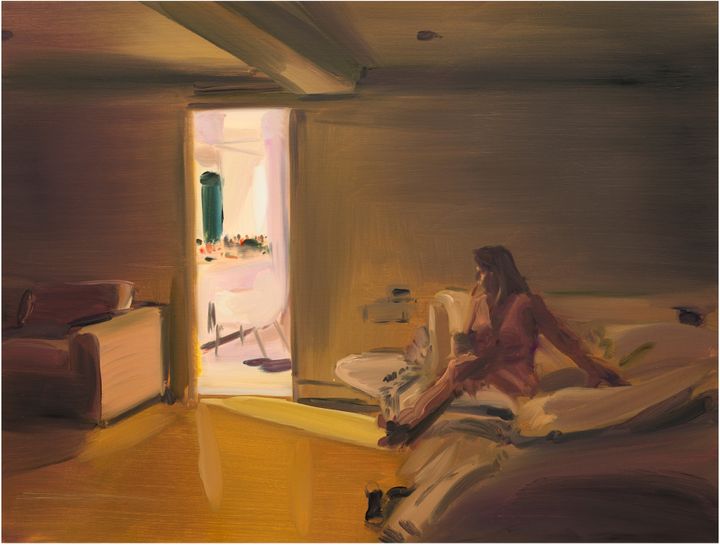

Caroline Walker, Study for Disturbed (2017). Oil on paper. 47 x 62 cm (unframed); 52 x 67 cm (framed). Courtesy the artist and GRIMM.

Part I (10 June–20 July 2023) focuses on figuration, and Part II (29 July–7 September 2023) on landscapes and the natural world. The show looks at how individual representative styles emerge and create emotionally heightened narratives based on both lived and imagined experiences, addressing themes relating to the personal and public, intimacy, and identity.

I was interested in bringing together painters of different nationalities—American, Puerto Rican-American, British-Nigerian, Korean, British-Caribbean, Japanese, Scottish, and Chinese—to probe how figurative painting and landscape painting, genres that have existed for centuries, continue to be a rich and important area of art that artists continue to reinvent.

Jonny Negron, Poison (2023). Acrylic on linen. 38 x 38 cm. Courtesy the artist and Château Shatto.

Most striking is how each artist deconstructs and reimagines academic techniques, art-historical references, pop culture, and figuration in depicting intimate, quotidian lives, interior spaces, nature, and landscapes.

This opportunity came about through conversations with Pond Society’s art advisor Irina Stark and the founder Mr. Xue Bing, who wanted to invite for the first time a guest curator to present new and recent works from a younger generation of artists for their summer show. Most of the artists are showing in China for the first time and are really excited to engage with a new audience.

Tunji Adeniyi-Jones, Triple Dive Red II (2023). Oil on canvas. 172.72 x 233.68 cm (unframed). Courtesy the artist and Morán Morán Gallery.

MAJ: Could you talk us through the highlights of this exhibition?

JD: While in recent years there has been a resurgence of interest in figurative painting, particularly in the context of contemporary African art—for better or worse—I was interested in bringing together artists of the same generation to probe the ways age-old, familiar tropes are being rethought and subverted.

Tunji Adeniyi-Jones, for example, has turned to West-African aesthetics in his paintings as a dedication, homage, or medium of preservation of his Yoruba roots. He considers this from a diasporic perspective as a British-Nigerian based in Brooklyn, bringing Modernism together with Yoruba folklore. He has cited artists and writers including Amos Tutuola, Ben Enwonwu, Aaron Douglas, and Clara Etso Ugbodaga-Ngu as influences.

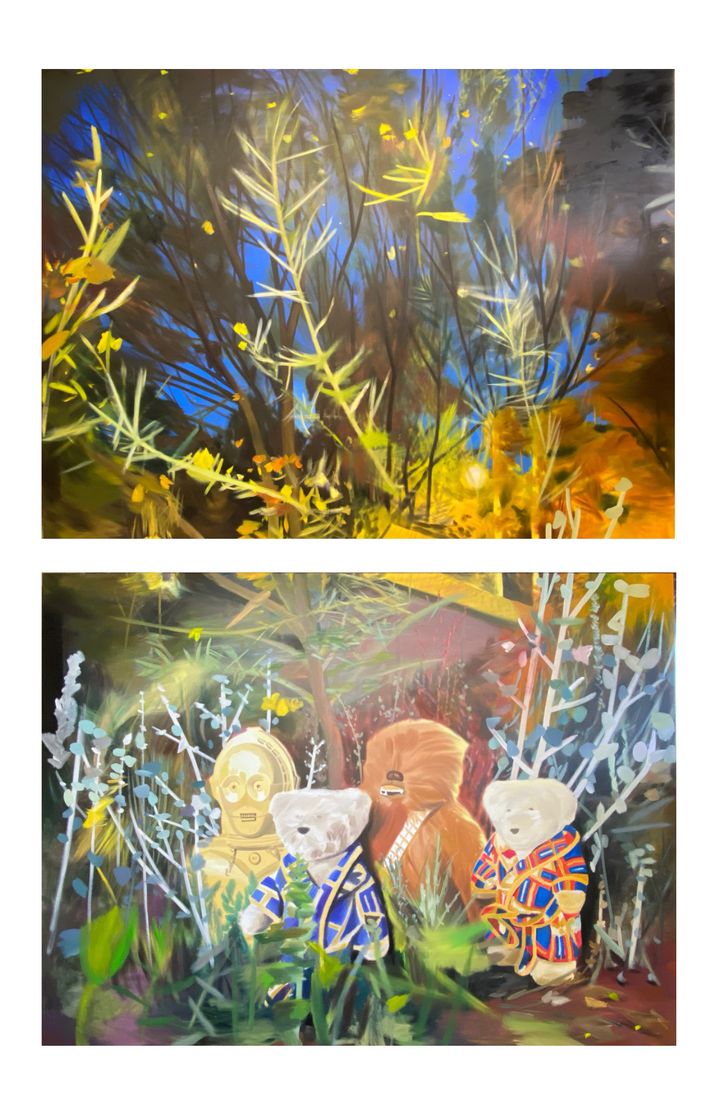

Ulala Imai, Encounter (2023). Oil on canvas, two parts. 194 x 259 cm each; 388 x 259 cm total. Courtesy the artist and Nonaka-Hill.

Imai transforms children’s toys, quotidian foods, and other household items into mysterious and lifelike subjects that take on new meaning in reimagined worlds. Working mostly in oil, her luminous paintings are a new take on still life that turn the materials of her family life into repositories for the more universal human exchanges that surround them.

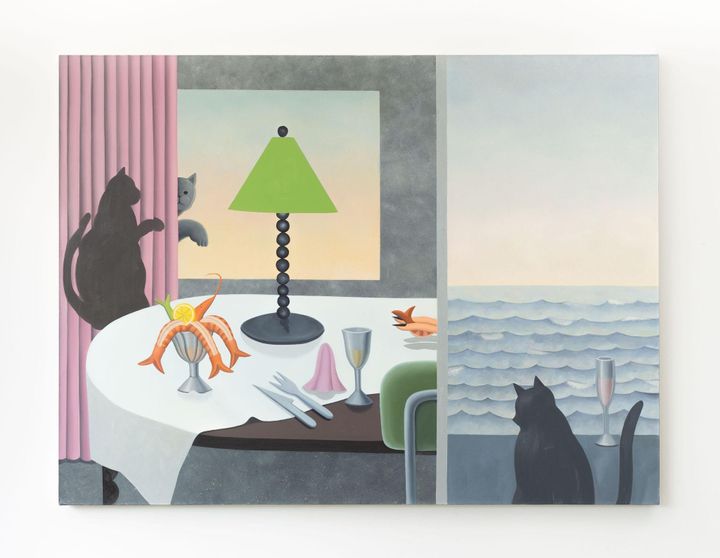

GaHee Park, Cat with a View (2022). Oil on canvas. 152.4 x 203.2 cm. Courtesy Perrotin. Photo: Marion Paquette.

Caroline Walker, GaHee Park, and Anthony Cudahy paint figurative scenes that deal with interiority and intimate quotidian lives. Park’s work Cat with a View (2022) dismantles hierarchies between humans and non-humans—the work centres on a cat in a contemporary apartment, and it is as if we are looking at domestic space through the animal’s perspective.

Park is playing with a new language of painting, exploring depth and flatness to free herself from realistic depictions of distance—both physically and psychologically. As she explained to me, she imagines the perspectives of animals, plants, or objects to disrupt the traditional still life genre, offering conceptual freedom in her paintings.

Sarah Slappey, Slip and Fall (2023). Oil and acrylic on canvas. 183 x 165 cm. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Maria Bernheim.

Hyegyeong Choi and Sarah Slappey deftly deal with a rejection of beauty and ideals projected onto women’s bodies. Choi is Korean and her figures address the high standards of ideal beauty imposed on women in her country. Painted in thickly layered brushstrokes, her works deal with body image, identity, gender, and sexuality in a liberated manner with her characters exploring ecstasy and indulgence as well as subconscious desire.

In a similar way, Sarah Slappey looks at American girlhood and her experiences of growing up in South Carolina, and what she sees as a cruelty inherent in a rigid femininity that promotes pristine-ness and perfection. Her painting depicts charged objects from these memories together with cropped and abstracted bodies that are recognisably feminine, yet not easy to decipher.

These are some examples of how contemporary painters are constantly revising and reimagining the genre, something that feels timely to explore.