- Source: MoMA

- Author: Erica Papernik-Shimizu

- Date: APRIL 14, 2023

- Format: DIGITAL

The Revolutionary Phone Line That Expanded Poetry’s Reach

Explore the six-decade evolution of John Giorno’s Dial-A- Poem and its impact on poetry, activism, and everyday life.

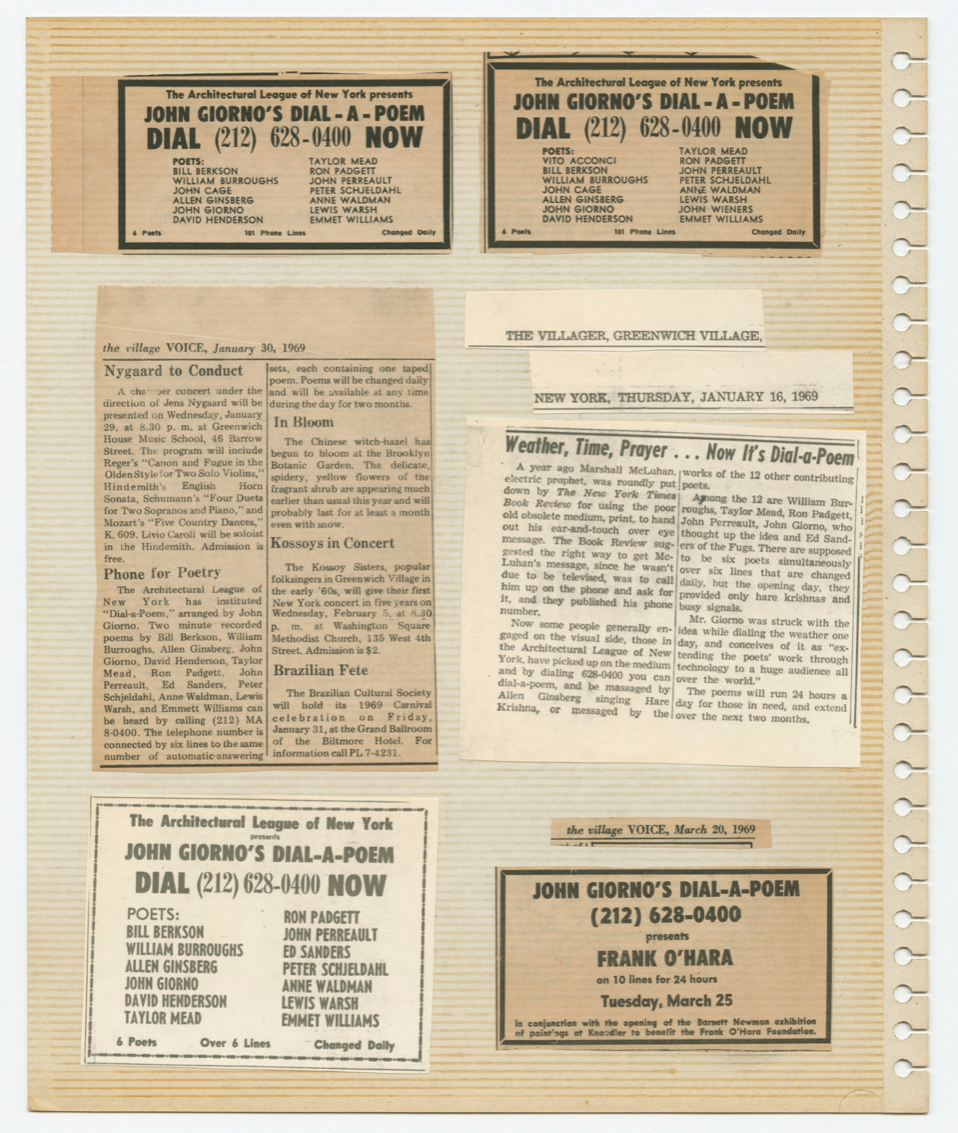

John Giorno. Page from artist’s Dial-A-Poem press scrapbook. 1969–70. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the

generosity of the International Council of The Museum of Modern Art in honor of Kynaston McShine, 2018. © 2023 Estate of John Giorno

This public service announcement, which introduced Dial-A-Poem when it was presented at MoMA in 1970 as part of the landmark Information exhibition, captures the ambition of John Giorno’s groundbreaking project.

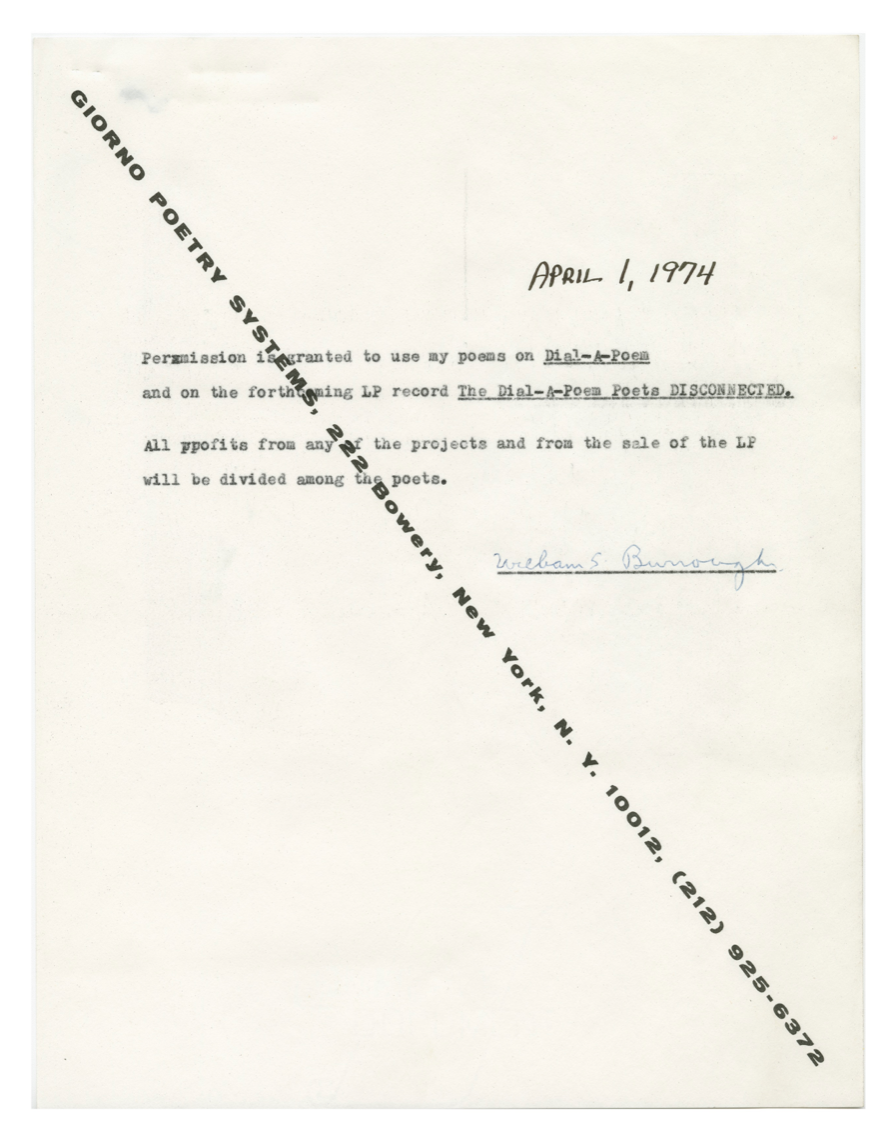

In 1968, Giorno launched his first Dial-A-Poem hotline in New York, which transmitted recorded poems to millions of callers throughout the city, instantly and free of charge. Dial-A-Poem has evolved in various iterations over six decades, expanding poetry’s reach as well as the definition of who can be considered a poet. In Giorno’s words, “Poetry is not, should not, cannot be confined to the printed word.” During his lifetime, he presented the project in a gallery setting on three occasions: at the Architectural League of New York in 1968, at MoMA in 1970, and again at MoMA in 2012. Throughout, Giorno added recordings by wide-ranging figures from his interdisciplinary network of peers that included artists, musicians, and political activists. Giorno described Dial-A-Poem in 1970 as a collage of works by other practitioners; it is a testament to his ability to connect with people and to bring together both contributors and listeners, bridging genres, disciplines, and generations.

This collaging of voices and language invokes Giorno’s own innovative practice of found poetry, which grew partly out of Pop art and combined text from magazines and other print media. Similarly, Giorno selected the works comprising each version of Dial-A-Poem in response to a particular cultural moment. Galvanized by the urgency of social issues, including opposition to the Vietnam War, more than three-fourths of the texts included in the 1970 version were by radical poets and political activists, “because what they have to say is so important now,” Giorno wrote. It included Abbie Hoffman, a member of the Chicago Seven; Bobby Seale and Eldridge Cleaver, leaders of the Black Panther Party; and Bernadine Dohrn, a member of the Weather Underground. “At this point, with the war and the repression and everything, we thought this was a good way for the Movement to reach people,” Giorno wrote. Placing revolutionaries in the same category as poets was as much a statement about the intersection of art and activism—both of which “open up consciousness”—as it was a means to amplify their messages to the widest possible audience. The exhibition attracted widespread visibility. In a 1970 newsletter, MoMA director John Hightower noted that the project had caught the attention of the FBI—federal agents spent a day at the Museum listening to Dial-A-Poem.

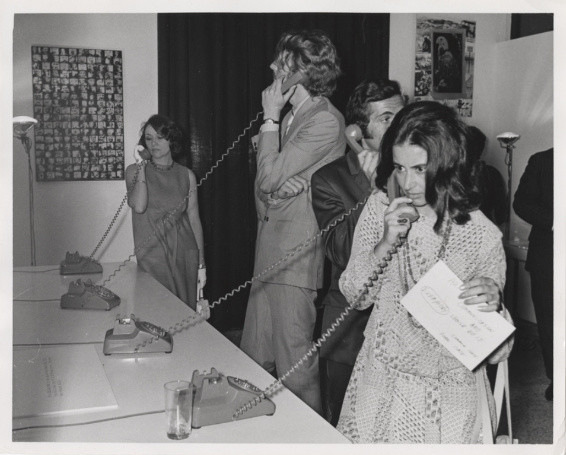

Installation view of John Giorno’s Dial-A-Poem in the exhibition Information, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, July 2–September 20, 1970. Courtesy of the John Giorno Foundation

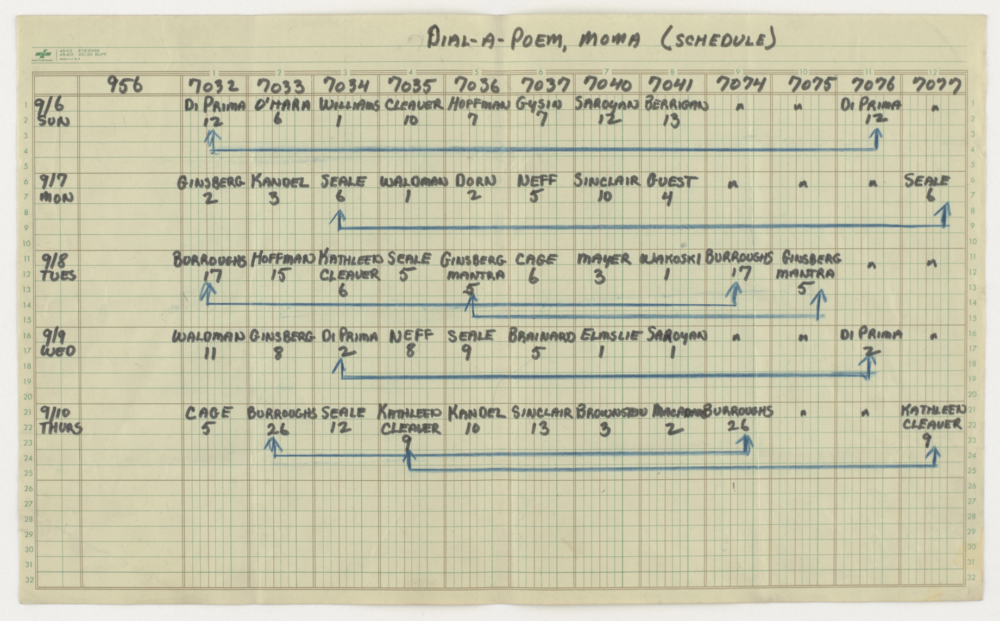

John Giorno. Dial-A-Poem schedule, MoMA. 1970. Marker and pencil on paper. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Acquired through the generosity of the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art in honor of Kynaston McShine, 2018. © 2023 Estate of John Giorno

The use of telephone lines for art’s sake was itself an activist gesture. Dial-A-Poem relied on, yet pushed against, the infrastructure controlled by Bell Systems, the corporate conglomerate that monopolized the North American telephone services industry until its breakup in 1983. Anecdotes about Giorno contesting the phone company’s overcharges and other modes of sabotage1 provide a glimpse into the day-to-day process of maintaining the hotline, which utilized industrial-sized answering machines. Employing the telephone as “new media,” Giorno was part of a generation of artists and engineers dreaming of an interconnected world, seeking freedom from the limitations and conventions imposed by corporate networks, and transforming tools of mass media into instruments for creative expression. Whereas artist-led satellite experiments and guerrilla TV actions took shape in the public sphere, a great deal of Dial-A-Poem’s staying power owed to its quiet form of broadcast, which was experienced intimately: participants called from within the privacy of their homes, or clandestinely from their offices. Yet other callers could access the same poems (though not at the same time, or the line would be busy), absorbing the same words. That, too, was a form of human connection.

The current presentation of Dial-A-Poem at MoMA consists of six rotary phones, which contain 200 works selected by the artist in 2012 to play digitally and at random, alongside a selection of ephemera—schedules, lists, and archival footage—that sheds light on Giorno’s original method of meticulously arranging the poems. It’s a thrill to pick up the phone and hear John Cage’s voice speaking directly to you; the feeling is intensified when you’re in a room full of people doing the same thing. According to Giorno, “hearing the sound of a poet’s voice, the quality, tone, volume, and emotional vibration” was integral to understanding the works he collected. Regarded in New York as “the village poet” and worldwide as a cultural innovator, Giorno is perhaps best known for his performance poetry, which incorporated his entire body, from movement to breath. Just as he wove Dial-A-Poem into the fabric of society, at the core of Giorno’s practice was a firm belief in the synthesis of making art and being alive.

Permission form from William S. Burroughs

John Giorno. Dial-A-Poem. 1968/2012