- Source: SEEN BY BLACKSTAR

- Author: CAULEEN SMITH

- Date: WINTER 2023

- Format: PRINT AND ONLINE

Cauleen Smith in Her Own Words

Ahead of Drylongso's restoration, the artist reflects on filmmaking and creating space for Black girls to recognize themselves.

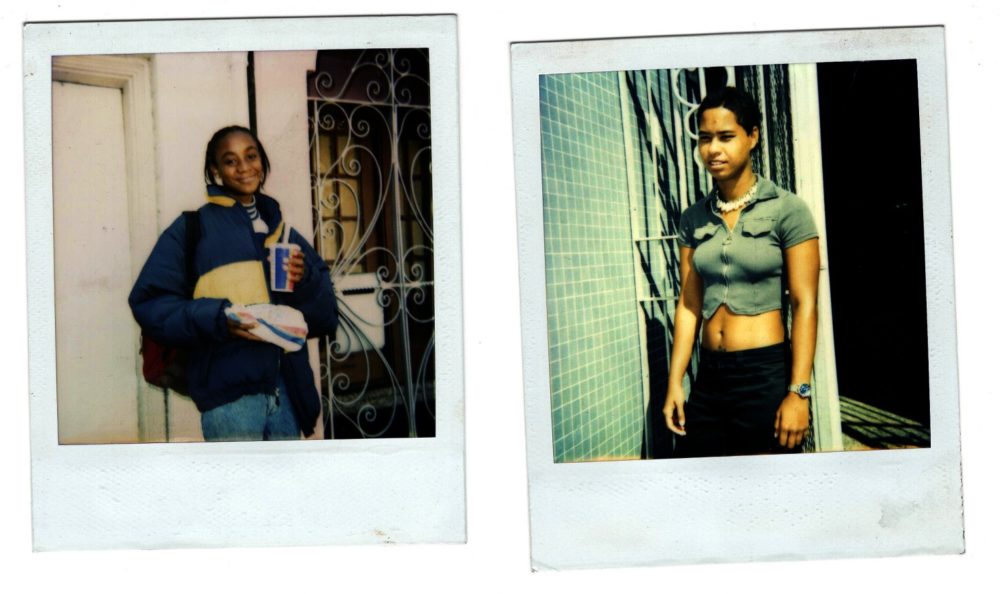

From Drylongso (1998), dir. Cauleen Smith. Courtesy Janus Films.

Drylongso was shot in West Oakland, in the summer of 1995. I started with $35,000 (before taxes) but a year of film school at UCLA and a toxic relationship depleted that stash by the time summer came and the shoot began. (While I did need that year of film school training, the relationship I really wish I’d done without.)

Our cinematographer, Andrew Black, used 16mm Fuji stock because my old San Francisco State film professor, Larry Clark, had encouraged us to look for film stocks that were responsive to melanated skin. He was right.

I start here because when Drylongso toured the film festival circuit from 1998-2001, the first two to three questions I was asked were inevitably about camera, film stock, and budget, followed by a few about production design and score. And then, every time, a well-intentioned cis white woman would stand up and ask me what I thought we should do about the problems of young Black men. Occasionally, if things got spicy, someone would ask me why the lead characters suppressed their lesbian desires for one another.

On the set of Drylongso. Courtesy Cauleen Smith.

When audience members, film journalists, and panel moderators asked me to speak on the pathology of the Black community and what could be done about it, I was and still remain bewildered. Why direct a question best aimed at social workers and public policy makers to an independent filmmaker? But Black film—whether it be documentary or fiction—has long been assigned the role of educating and elucidating liberal white audiences, and/or rectifying historical omissions or errors of representation. Films that refused this service were summarily ignored and dismissed as narrative structural failures. Here I’d cite the films that emerged out of the LA Rebellion Era, which were rejected for their focus on Black interiority and complexity, which had no currency in critical cinematic discourse.

Each and every Q&A for Drylongso became an exercise in defending the work strategically. For the sake of the film, I could not appear to be defensive. I’ve spent so much energy trying to figure out how to defend and protect this film, that I hardly know how to speak of it any other way. I really cannot express the depth of absolute boredom and despair that these questions induced in me. It was a relief to walk away from this film and let it live its afterlife in VHS obscurity.

Drylongso is a film about two Black girls, each experiencing a kind of jeopardy and isolation, each looking for a way to escape.The tools at their disposal were limited, as were mine as the filmmaker. Back then, baggy clothes were the armor of the streets. They protected the Black body from the extreme surveillance we were and still are subjected to. Baggy pants and a hoodie could hide a weapon, cash, or groceries. Depending on how these clothes were worn, they could also obscure gender, which came in extremely handy when one was in need of mobility. We didn’t have the language we have now to talk about why and how that mattered, to talk about being cis-gendered or the jeopardy faced by Black trans women.

I developed the script for Drylongso over the span of several years. If I recall correctly, I thought it might become a short film. While outlining Pica’s story, I started taking my Polaroid with me everywhere. I would approach young Black men and ask if I could take their picture. Inevitably, they would ask why. My response was pretty much what Pica says in the film, “I am documenting the presence and faces of young Black men because they are an endangered species.” Most would simply shrug and pose and make small talk while we waited for the image to resolve. This was the nineties. Violence was at a surreal level. Oakland’s Highland Hospital became known for training military medics because in their emergency room, one could see all types of gunshot wounds, just like on a battlefield. I don’t remember ever attending a hip-hop show without gun fire popping off. Indeed, we were living on a battlefield and in the wake of HIV and ACT UP.

The scenes reproduced here all hinge around the slippage and play between Pica’s collection of Polaroid portraits of young Black men and her Orisha tarot deck, which she takes with her everywhere. The Tarot deck pops up again and again in this film, offering a device through which Pica can understand her fate or future. At times, tarot cards give way to the Polaroid portraits, replacing the Yoruba Orishas with the visages of young Black men.

On the set of Drylongso. Courtesy Cauleen Smith.

In a scene with Pica’s photography instructor, the Polaroids predict the inevitable extinction of Black men. The Polaroid as tarot trope also pops up when Pica is waiting for the bus and fails to recognize Tobi. Their conversation revolves around the strength of Tobi’s performance of masculinity—comical, since her performance of masculinity is not what’s at stake, so much as her desire to go unseen or unrecognized. Later, in the clothesline scene, the Polaroids once again function as a divination device, offering these women a way of recognizing themselves in one another.

And so I guess that’s what I hope for this film. That a film which did not have all of the language, nor bandwidth to accommodate contemporary discourses because it was desperately attempting to complicate the cultural climate of its day, can create a way for Black girls to recognize themselves.

Sadly, the world we live in now is no less dangerous. We just have better tools to describe our condition and comprehend our experiences. These pages are plucked from a 74-page shooting script. As I re-read the script I was shocked by how threadbare each scene was. It’s as if I was writing with the knowledge that my film budget for each day could only be three to five rolls. We shot every scene, but there were some things I cut. The script was actually much darker than the finished film. But the segments here are full of tenderness, dreams and longings; the things I still love watching Black people enact in film.