- Source: FAD MAGAZINE

- Author: MARK WESTALL

- Date: DECEMBER 11, 2020

- Format: ONLINE

KENNY RIVERO’S NEW PAINTINGS POETICALLY EXPLORE HIS “FEAR OF DEATH AS A PERSON OF COLOR IN AMERICA”

Kenny Rivero portrait photo by Elizabeth Brooks

Interdisciplinary artist Kenny Rivero presents autobiographical series of new paintings that poetically explore his “fear of death as a person of color in America” through the lens of Dominican-American identity.

Charles Moffett are showing I Still Hoop, a solo presentation of 17 new paintings by New York-based visual artist and musician Kenny Rivero (b. 1981, New York; MFA Yale, 2012). All of the works were made during the seismic cultural reckoning of 2020. Heightened by the recent police-committed murders and injustices toward people of color, at the top of Rivero’s mind has been the breed of fear that he first internalized as a child growing up in a neighborhood that was disproportionately affected by street violence and the Crack Epidemic.

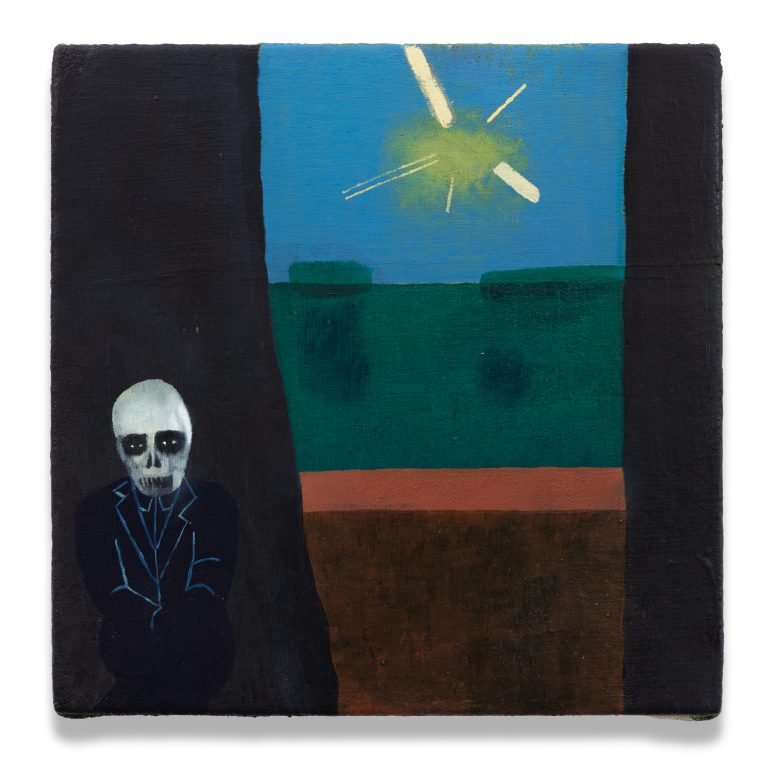

Kenny Rivero – Terrace 2020 Oil on canvas stretched over panel.

Overall, the exhibition—which is set in an abstracted landscape informed by the people, architecture, culture and aesthetics of Washington Heights in New York (more broadly, uptown and the Bronx) and the Dominican Republic (more specifically, Santiago and el Cibáo)—combines historical and cultural references with Rivero’s own memories and experiences in order to examine the power of fear, death, spirituality, and resilience.

The exhibition’s title, I Still Hoop, is a triple-entendre. Most literally, it is a playful phrase from Rivero’s culture growing up that is used to be “braggadocios and flex a little bit, taken from basketball vernacular and usually said to reassure someone who may believe that you’ve peaked and can no longer keep up.” Secondarily, I Still Hoop is the name of a painting that thematically represents the body of work as a whole – its core figurative focus is a woman wearing large hoop earrings, with styling characteristic of 1980s-1990s Afrodiasporic Americans.

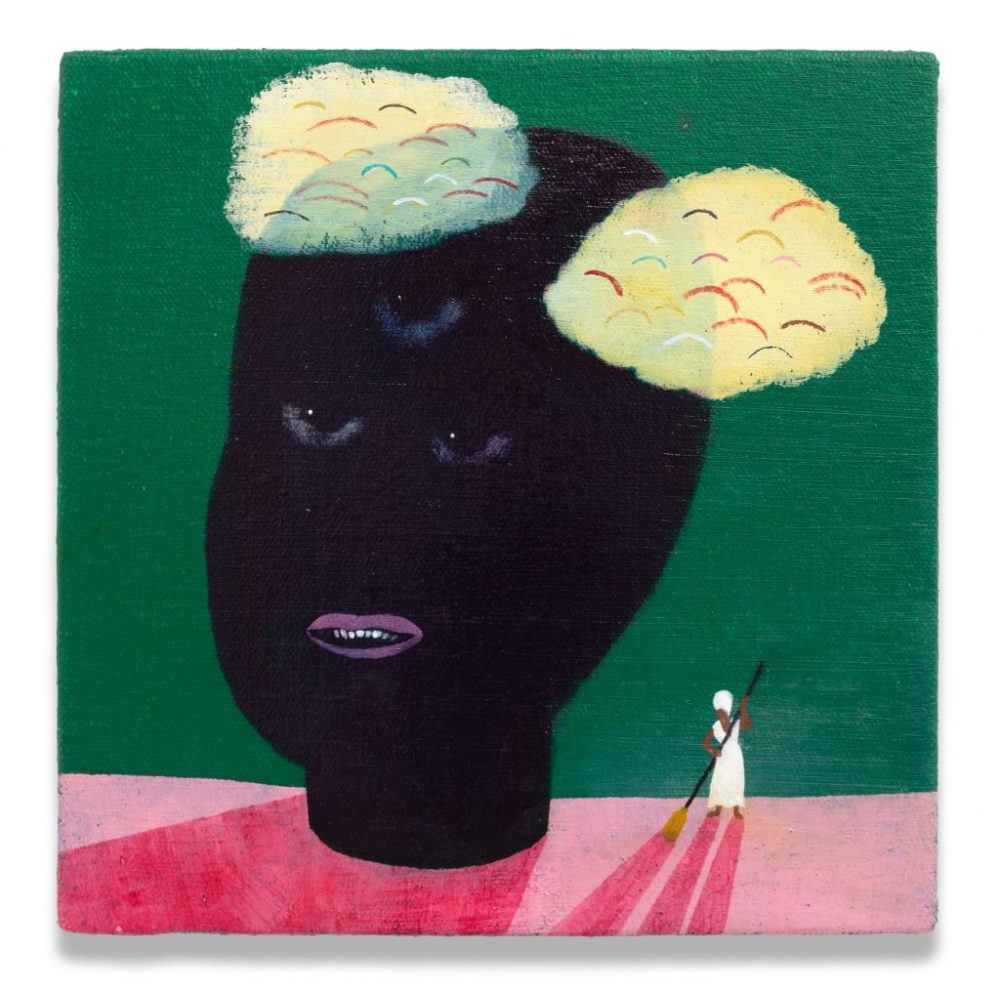

Kenny Rivero – Limpieza of the Head 2020 Oil on canvas stretched over panel

And finally, in a larger sense, the exhibition’s title correlates with Rivero’s lifelong cultural ethos of resourcefulness and thinking creatively about how to expand with limited resources; “I Still Hoop” is an affirmation of resilience. While the works are imbued with playfully nostalgic markers of Rivero’s 1980s-1990s New York upbringing—like pink-and-teal interiors, and the title work’s representation of a Dominican woman with large hoops, high waisted pants, and a voluminous hairstyle—Rivero explains that the show speaks more broadly to the enduring lived experience of people of color in America, and what that looks like in the current political landscape.

“Death is always something I’ve lived with, especially growing up in Washington Heights at that time,”

said Rivero.

“In a lot of ways, you could say that things have calmed down from that, but there’s other things that have escalated too. Coming back from teaching in Massachusetts the other day, I was followed by a cop for 10 or 12 miles, really close on a highway that was otherwise wide open without any traffic. I was like, ‘should I let him pass?’ I switched lanes and he followed. It felt like an eternity until he pulled off, and the entire time I was terrified and legitimately fearing for my life. No matter how successful I am or whatever neighborhood I move to, there’s always this fear of death and having to behave. There’s this watching out and vigilance that I always have to have. The work in the show, even when it’s not overtly figurative, depicts the lives of people who are being overstimulated by being careful and having to be cautious. So that resilience enters that space where I’m being defeated by a racist president, by a racist police force, by this deadly virus, I still hoop. I still have to go out there and do what I need to do. That’s not always easy.”

Rivero

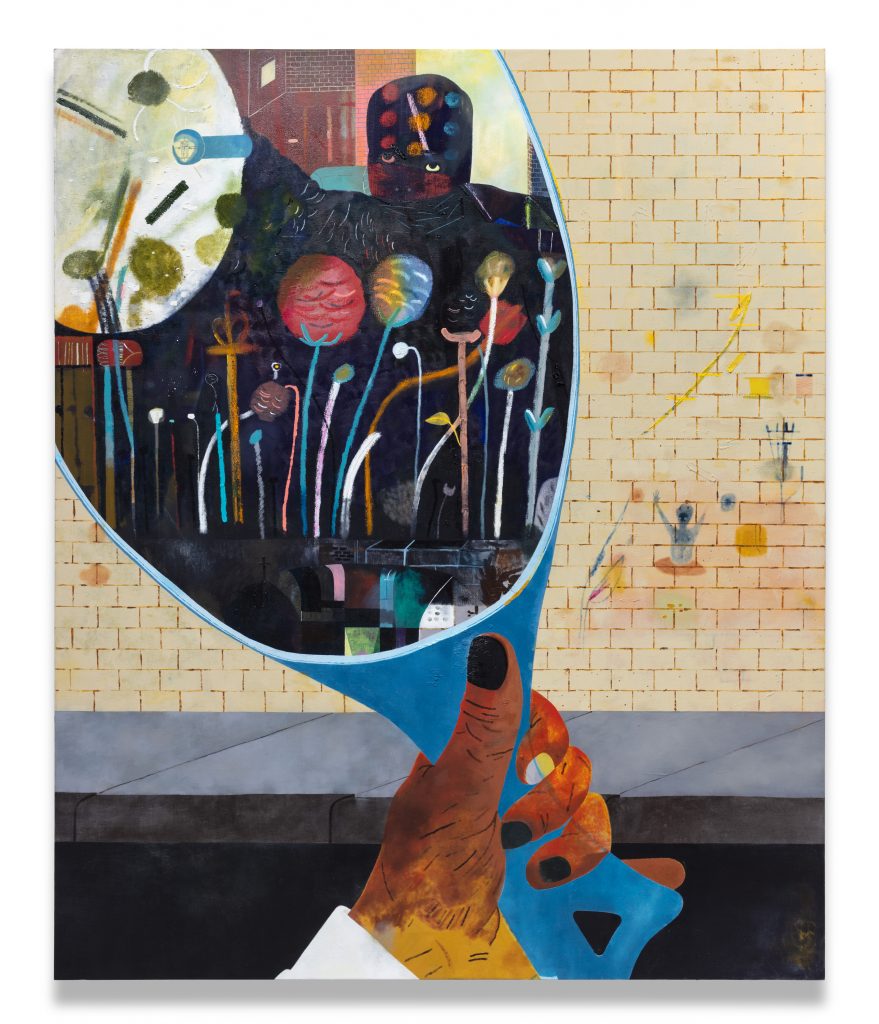

Kenny Rivero – Swimming in the Babel 2020 Oil on canvas stretched over panel

Rivero is a trained musician and his time in the studio alternates between visual artmaking and music. In addition to art supplies, his 400-square-foot Bronx studio is packed with a drum set, keyboards, guitars, and various percussion instruments. When he paints, he feels that his hand moves in a system that is more connected to music than to painting in a traditional sense; as one example, all of his paintings start with him “shuffling” paint around on the canvas in a rhythmic fashion that correlates with the music he’s listening to, and the works improvisationally find their narrative or figurative focuses along the way. Rivero’s days in the studio are typically structured around painting (while listening to music) in the morning and playing music in the evening. He cites the hybrid qualities of salsa, hip-hop, house music, jazz, R&B, Afro-Caribbean folk music, 1960s rock, and merengue as core influences in his artistic decision-making.

Heavily embedded across Rivero’s work is his family’s history prior and subsequent to his mother and father’s respective immigrations from el Cibáo, a relatively rural region of the Dominican Republic, to the Bronx and Washington Heights, where they met and married in 1966. Both had come to the U.S. as part of the Dominican emigration wave that followed the 30-year dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo, under whose systematically oppressive rule tens of thousands of citizens were arbitrarily murdered. In New York, Rivero’s mom was a seamstress and hairstylist, and his dad was a mechanic who landed at a pen factory that Rivero and his siblings later worked at as well. Rivero started working as a doorman in Gramercy Park in 1999, while still in high school. That skill set qualified him for a custodial job at David Zwirner in 2007, a role he held for three years until enrolling for his MFA.

Another predominant aspect of Rivero’s life and art practice, tying into his perpetual fear of death as a person of color in America, is how his hybrid faith—stemming from a diverse religious upbringing that incorporated Christianity, Vodun, Santeria, and other Afro-Caribbean influenced spiritual practices—has informed his complex relationship with the idea of death.

“Faith has always been a comforting way to ‘prepare for dying,’ as a way to cope with that perpetual fear. The work often references a parallel world that may be the afterlife—it’s almost dreamlike, combining so many aspects of my life and subconscious. The scenes are loosely familiar but feel like something is ‘off’ and not quite realistic. The more mystical aspects of my own spiritual practice are where my faith comes into the paintings. In my community growing up, my aunt was a well-known reader of Barajas, a Tarot-like divination tool that uses a Spanish card deck, where you can communicate with the ancestors. The work speaks directly to that, knowing that I’m part of a legacy that has an ability to connect with spiritual energies. Growing up, there was always death in the air like that. And in the paintings, a lot of the little symbols, the numbers and letters, they’re about communing with that other side.”

Explained River

Kenny Rivero – Vision of Church Flowers Oil on canvas

Regarding what appears to be symbolism, such as a bloody rose (also prominent in Rivero’s work New Hat, which is in the permanent collection of the Pérez Art Museum Miami) or a grouping of numbers and letters: Rivero works without advance studies; his process is mostly improvisational and subconscious, and he often identifies meaning along the way. Recurring formal motifs include paint layers and concentric planes with curved edges that Rivero has come to recognize as metaphors for the intergenerationally influenced nature of being first-generation Dominican-American. As part of his creative process, many paintings take on unusually dramatic compositional transformations into entirely new works. He recalls a childhood fascination with chipping paint off walls in order to see the history of past layers, and now sees his frequent painting-over as a sort of revers manifestation of this. Another recurring motif is mirrors; plastic mirrors were always plentiful around Rivero’s childhood home, and in his work, he uses them as portals for discrete explorations.

The works feature many aspects that allude to objects or elements of a Dominican-American upbringing. Most principally, the work itself takes place in an imagined locale that combines Rivero’s parents’ homeland of rural Dominican Republic with the concrete landscape of Washington Heights and the Bronx. For instance, one painting, Lamps and Socks—which Rivero considers to be the most playful piece in the show—”riffs on the stereotype that Dominicans don’t like to wear socks,” he explains. The work itself, which takes place in a characteristically ‘New York’ street at night, depicts all of the socks sneaking out to gather and have fun since according to the stereotype, they don’t otherwise get to go outside. Rivero’s use of light in the painting nostalgically represents the dim glow before the sun comes up, which he often experienced in his role as an overnight-shift doorman. In another painting in the show, Five Teeth, a similar combined-culture formal influence is a particular atmospheric light that Rivero associates equally with autumn in New York and summer in the Dominican Republic.

Kenny Rivero – I Still Hoop 2020 Oil on canvas stretched over canvas

Rivero makes his own paint, sourcing powdered pigment and combining it with a homemade recipe of oils, beeswax, and solvents. Tying into the historical and intergenerational aspects of his practice, he prefers to work with historical art materials rather than prefab polymers. Whereas his practice has typically entailed the integration of mixed media and found objects, I Still Hoop is Rivero’s first body of work composed entirely of paintings. Overall, the work uses cultural markers as a way to contextualize one individual’s set of circumstances as they relate to the larger conversation about living in America as a person of color.

“All of these things do represent a resilience and a cultural identity, but underneath it, there’s some real violence and real trauma. I want to play with the mess. I don’t want to play with the clean, cookie-cutter image of things. The paintings always deal with a loss – a loss of a loved one, a neighborhood, a certain geography, a time. Fear of death is looming in general, and some of us don’t have a choice but to live with the constant thought of mortality.”

Explains Rivero