- Source: FORBES

- Author: BRIENNE WALSH

- Date: OCTOBER 28, 2020

- Format: ONLINE

Kenny Rivero Takes A Journey Through The Valley Of The Shadow Of Death

In A New Body Of Paintings

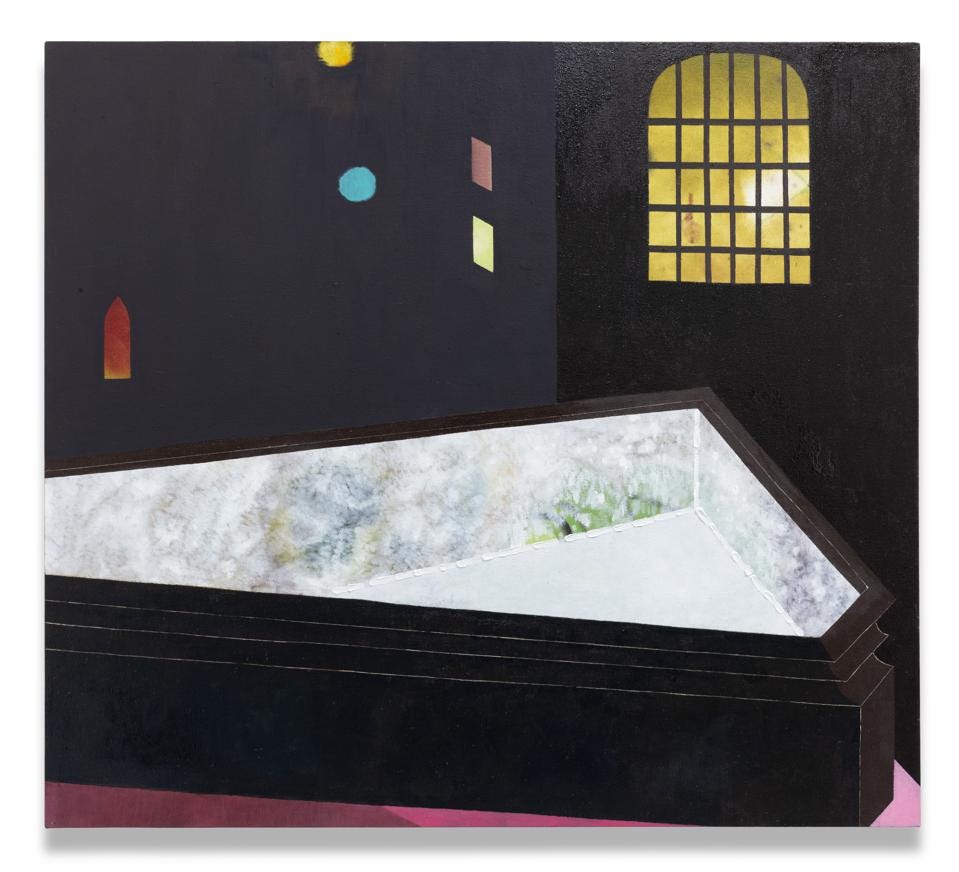

Kenny Rivero, The Passion, 2020, Oil on canvas 32 x 36 inIMAGE © CHARLES MOFFETT GALLERY

There’s an overwhelming sense, looking at Kenny Rivero’s paintings, that they’re taking you on a journey somewhere — for me, that journey is back to a street in New York City late at night. I have my headphones in, I’m listening to music that makes me feel in love. The city isn’t quiet, but it’s empty. The air is cold, and the lights emanating from windows are warm. I’m not scared, but I’m on guard, alive. I’m living past, present and future at once.

Rivero told me that when he was working as a doorman in the early aughts, he used to walk from the building in Gramercy where he worked back up to Washington Heights, where he grew up with his Dominican parents and two siblings. “It was midnight, and I could just own the street,” he told me. “There an intimacy from being able to look into people’s windows that you don’t get in the daytime.”

Kenny Rivero, I'm Dead, 2020, Oil on canvas stretched over panel, 10 x 8¼ inches

IMAGE © CHARLES MOFFETT GALLERY

In “I Still Hoop,” an exhibition of 14 works by Rivero that opens on October 29 at Charles Moffett gallery in New York, you can almost see Rivero’s thoughts on those walks unfurling. Rivero, who began making the paintings in January of 2020, set out to make a cohesive body of work. The theme he arrived upon was death — how people die, where they go, and what the in-between spaces between life and death looks like. How, he wondered, do the dead cross into the world of the living?

Rivero, of course, could not have predicted how his images of death would resonate so deeply in 2020, a year with a pandemic and a fierce reckoning over the deaths of black bodies at the hands of police officers.

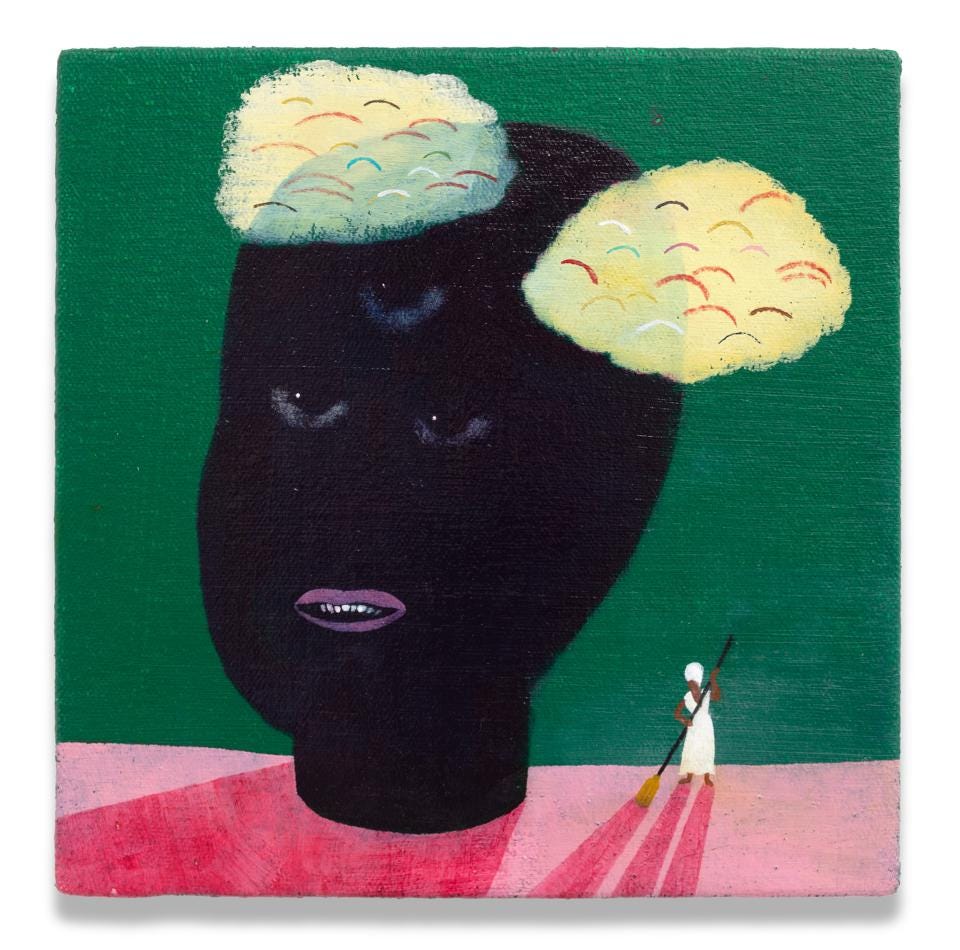

Rivero was raised Catholic, but his mother’s family, he noted, practiced many rituals associated with voodoo, santeria and other faiths of the Afro-Caribbean diaspora. In particular, he was drawn to the way that his maternal family created altars to the spirits of ancestors. “They made me understand how materials can charge a space,” Rivero says. When he was creating the paintings for “I Still Hoop,” he thought about how paintings, like objects on an altar, can be combined to create a frequency with one another.

Kenny Rivero, Limpieza of the Head, 2020, Oil on canvas stretched over panel, 8 x 8 inches

IMAGE © CHARLES MOFFETT GALLERY

Each of Rivero’s paintings began with his body. He thought about how he wanted to use his appendages — his elbow, his wrist — in the creation of the painting, and then went from there. Rivero began drawing during Confraternity of Catholic Doctrine (CCD) classes he attended in his youth. A teacher would read a bible passage, and then ask the class to draw what they learned. Rivero quickly found that drawing was a portal to privacy in the small apartment he shared with his family. He still remembers a drawing he made of Jesus and a dinosaur.

Drawing, an escape, remains a part of his painting practice. Paint was a medium that Rivero felt was elitist during his first years in art school — he graduated with a BFA from the School of Visual Arts in 2006, and an MFA from Yale University in 2012. He found access to the medium when he considered the peeling paint on the walls of the apartment where he grew up. “I was fascinated by paint chips, and thinking about crumbs and bits of something, buried underneath decades of paint, which serve as a kind of time capsule,” he says. “All of my paintings have paintings underneath them. Their lives have a lot to do with what came before them.”

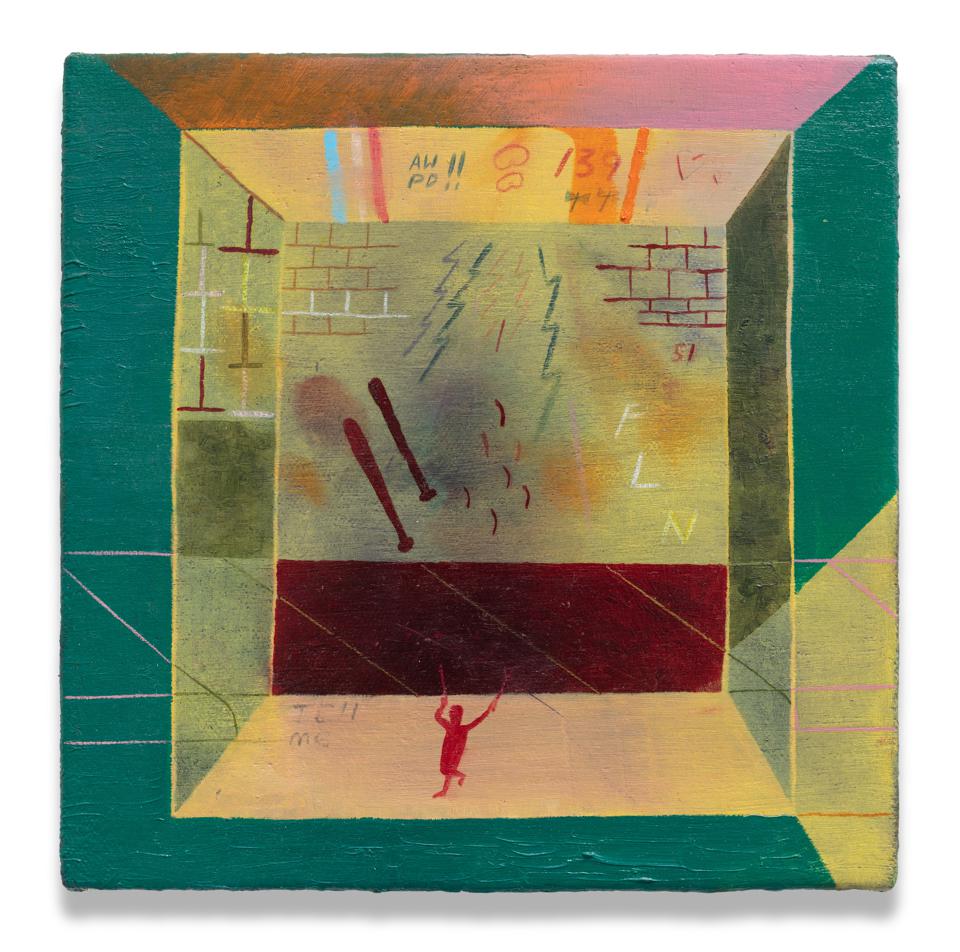

Kenny Rivero, AW PD!!, 2020, Color pencil, graphite, pastel and oil on canvas stretched over panel

IMAGE © CHARLES MOFFETT GALLERY

But mostly, Rivero’s paintings relate to his own body. Rivero is arguably more aware of his body than most, considering that it is the body of a black man. As such, Rivero’s body is in peril on a daily basis. It has been in peril for as long as he can remember. As a child growing up on the streets of Washington Heights during the crack epidemic in the 1980s. When he was a scholarship student at the Buxton School in Williamstown, Massachusetts, where he was first arrested for making out with his girlfriend in a cemetery after dark. When he was a custodian at David Zwirner in Chelsea, where his body moved in supplication among the work of artists including Chris Ofili, Mamma Andersson and Marcel Dzama. As a teacher today at Williams College, back again in Williamstown, where he finds the trauma of his teenage body held in handcuffs still lingers. When he walks down the main street of the town, he says, everyone says hello to him. “For me, it’s this veiled kindness,” he says. “It’s not really a gesture of being nice. They’re telling me, ‘I see you.’”

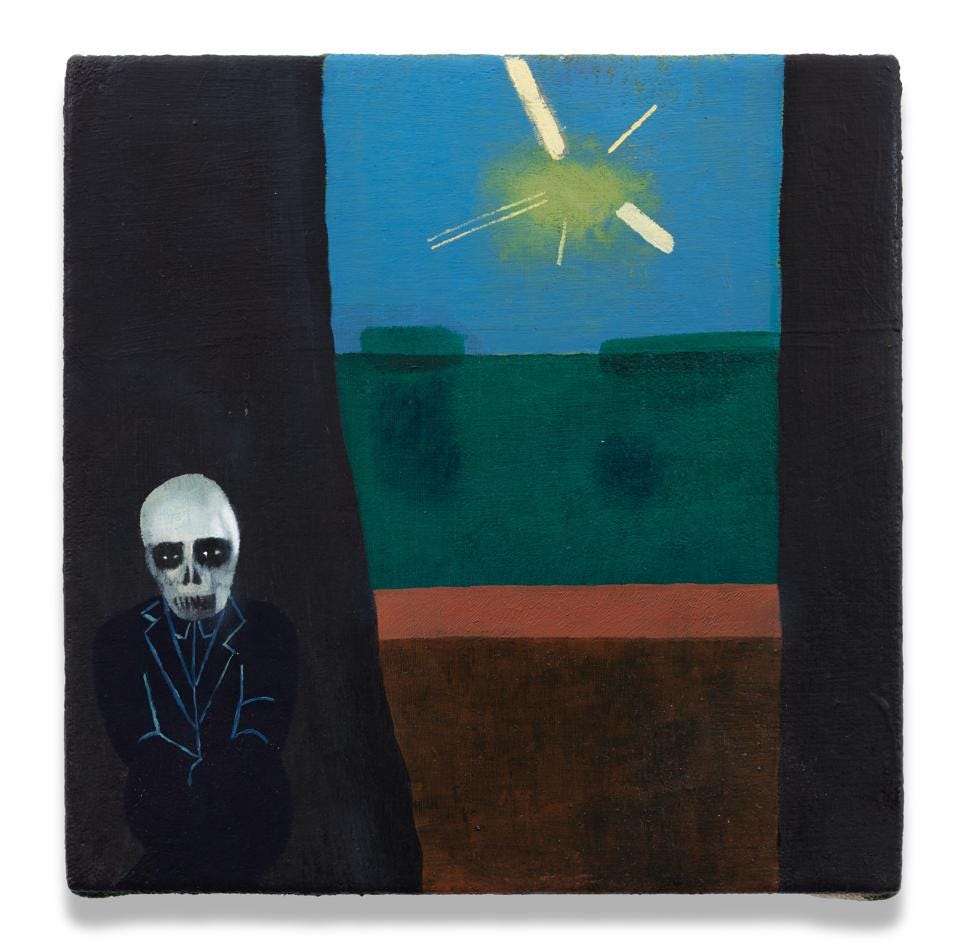

Kenny Rivero, Five Teeth, 2020, Oil on canvas 12 x 9 inches

IMAGE © CHARLES MOFFETT GALLERY

Rivero’s paintings show the presence of death at every turn. Five Teeth (2020), an abstract work in the vein of Bauhaus, jerks the viewer into realism with the presence of five brilliant white teeth. They reference the presence of teeth falling out in Rivero’s dreams, which his mother says points to death and violence. “When I was painting it, I was thinking about my nieces and nephews, who are in their twenties, getting stopped by the police for no reason,” he said. “They’re protesting, they’re out on the street, they’re driving.” He’s afraid for them, but he’s also proud of them.

Kenny Rivero, Terrace, 2020, Oil on canvas, 8 x 8 inches

IMAGE © CHARLES MOFFETT GALLERY

In both The Passion (2020), which depicts an empty coffin in front of a warmly lit window, and Terrace (2020), which depicts a skeletal figure in a tuxedo standing guard in front of a view of a sunny meadow, Rivero explores death not as an end, but as a process point. “Death is just a thing that is waiting like a toolbooth that you have to cross through,” he explains. “It’s not necessarily something you need to be afraid of.”

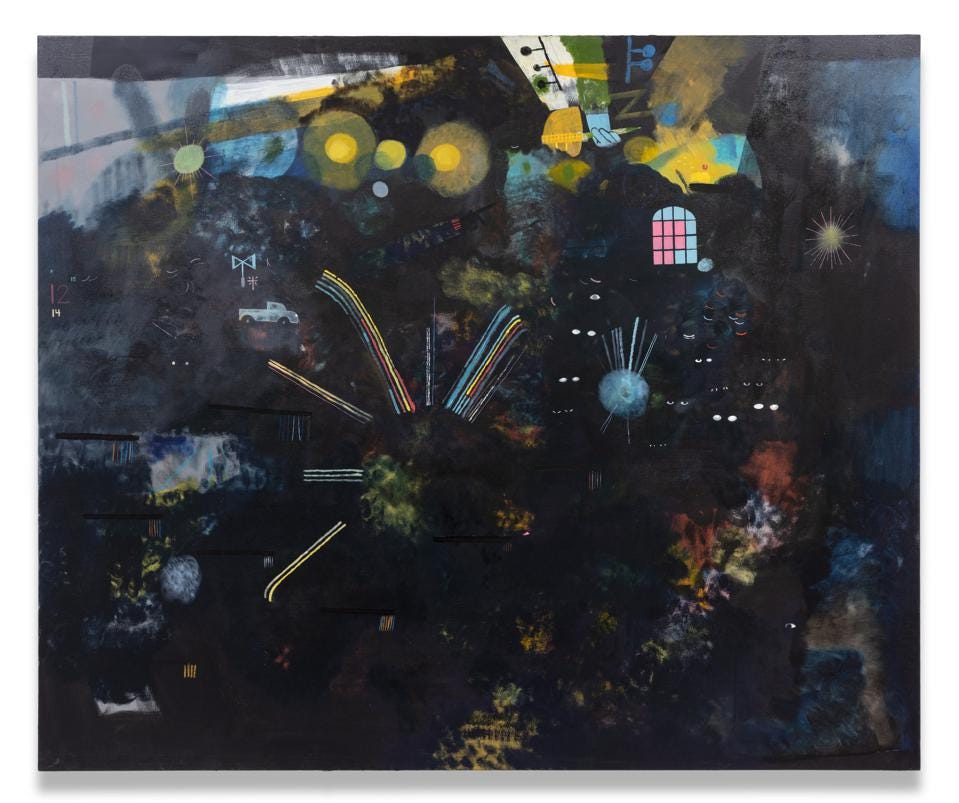

Kenny Rivero, Pink Windows, 2020 (First Completed 2016), Oil canvas, 60 x 72 inches

IMAGE © CHARLES MOFFETT GALLERY

Space, in general, is so adeptly captured in Rivero’s work. Dimensions crash into each other on the canvasses. Entire neighborhoods are encompassed in abstract two-dimension. Pink Windows (2020), shows a flat night landscape filled with fireworks, cars, music, the warmth of a church window lit against the dark, that somehow, within its layers, transmits a feeling of wholeness.

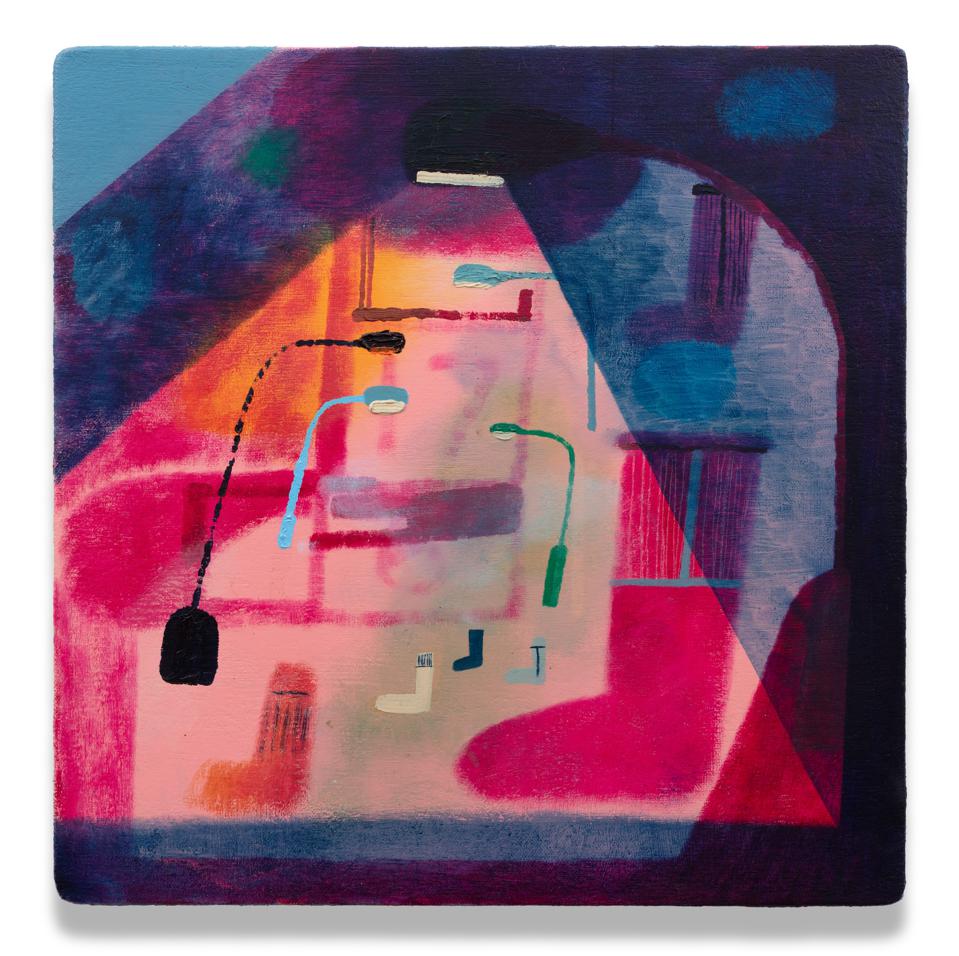

Kenny Rivero, Socks and Street Lamps, 2020, Oil on canvas. 13 x 13 inches

IMAGE © CHARLES MOFFETT GALLERY

Socks and Street Lamps (2020), shows the way that street lights collapse and shorten as you drive past them; combined with the red of stop lights, street lights create a gorgeous, lush, pink and purple glow.

“I want the viewer to see the beauty in the works,” Rivero said. “I want them to find beauty in these moments that are charged with death.”

Kenny Rivero, I Still Hoop, 2020, Oil on canvas stretched over panel, 8 x 8 inches

IMAGE © CHARLES MOFFETT GALLERY

Ultimately, what Rivero hopes is that the work transmits a feeling of resilience. In the titular work from the show, I Still Hoop (2020), a woman wearing a white turtleneck and hoops, holding a rose dripping with blood, warily casts her eyes upwards at some point in the distance. The work, Rivero says, was inspired by his sister, who used to get catcalled when she would walk down the streets of the neighborhood where they grew up. “My sister was terrified of the men, but she still celebrated her body,” he says. “By looking good, she maintained her semblance of power.”

Rivero feels responsibility, as an artist, to create work that brings to light conversations that he feels otherwise won’t be heard. In this altar of paintings he’s created, these paintings that pay homage to his own body, he collapses time and space to show that death is not the conclusion. “I’m not looking back in this kind of mourning or nostalgic way,” he says. “I’m thinking about flexing my muscles and coming out of this with resilience.”