- Source: THE NEW YORK TIMES

- Author: TANYA MOHN

- Date: OCTOBER 21, 2022

- Format: ONLINE

How Childhood Inspires Artists and Their Art

With works by 40 artists, the Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston examines many aspects of the lives of children.

The Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston has bold ambitions for “To Begin Again: Artists and Childhood,” its thematic group exhibition that explores how visual artists have been inspired and influenced by children and childhood, on view through Feb. 26.

“Children and childhood, their role in society,” said Jill Medvedow, the institute’s director, “their visibility or invisibility, their creativity, their resilience, and their plight, have for a long, long time — decades, centuries — been a source of interest, engagement and concern for artists.”

Combined with the “sense of urgency that we collectively feel about children” — from education equality and immigration to the impact of the pandemic — Ms. Medvedow said, “this show gives us the opportunity to shine a spotlight on children anew.”

More than 75 paintings, sculptures, photographs, drawings, videos and installations by 40 20th- and 21st-century artists are on display, from well-known ones like Paul Klee, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Faith Ringgold to many midcareer and emerging artists.

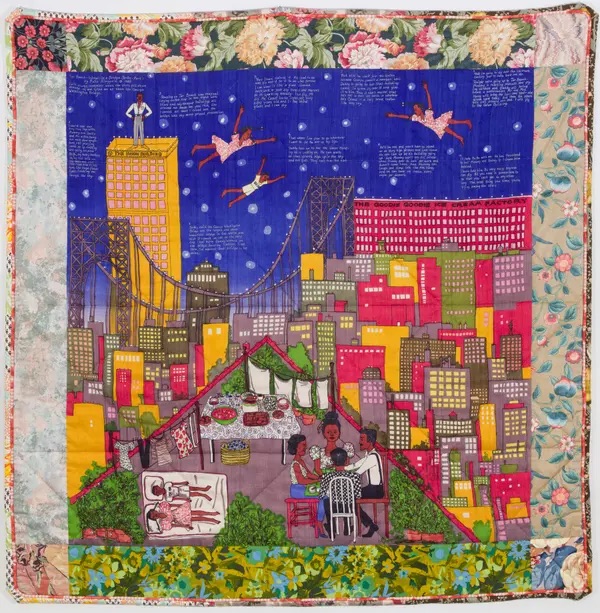

“Tar Beach #2” (1990-92) by Faith Ringgold.Credit...Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; ACA Galleries, New York

Topics include thorny issues such as how Black children are portrayed in popular media by the contemporary artist Deborah Roberts but also the work of Francis Alÿs of Belgium, who documented children all over the world playing games.

“They are magnetic,” Ms. Medvedow said. “You don’t want to stop looking at these incredible videos.”

Ruth Erickson, a senior curator who had the idea for the show, said that though there had been many exhibitions about childhood, this one takes a new approach. “The vast majority meant representational pictures of children, but the focus here is on artists and how the engagement with children or the cultural construct of childhood changed their practice,” she said. “At its heart, the project centers on a subject or an experience that might previously have been on the margins.”

The project started with a simple question to artists: What about childhood provided the spark that led you to embrace the topic in your practice?

“Artists talked about the beauty of a child’s scribble, the enchantment of a book’s page and the creativity of caretaking,” Dr. Erickson said. Those conversations ended up giving form to the exhibition’s six thematic sections.

An installation view from “To Begin Again: Artists and Childhood,” with works by Robert Gober and Mona Hatoum, foreground, and Deborah Roberts “Sisterly Love” (2021), center. Mel Taing

Among Children, in the first gallery, features a room of figurative sculptures of children. “The idea is that by walking amongst these works, visitors encounter the myriad ways artists have employed the child figure to evoke sentiments and experiences of joy, play, vulnerability, and resilience,” Dr. Erickson said.

“Some works are cast from the bodies of actual children, as in John Ahearn and Rigoberto Torres’s celebratory relief sculpture of a game of double Dutch or Karon Davis’s plaster sculpture of two girls playing patty-cakes.” The Mexican artist Berenice Olmedo uses a child’s castoff leg braces “to create a kinetic sculpture that appears to fall and stand in an unending cycle.”

Draw Like a Child explores the expressive and imaginative capacities of children and how they create art. The earliest piece in the show is a drawing Paul Klee made in 1884 when he was about 5 that he found on a visit home as a dissatisfied art student.

“It was an unexpected source of inspiration for him,” Dr. Erickson said. “The untutored form of mark making and the ideas of representation and abstraction were such an important influence in the development of his own oeuvre and arguably in the development of Modern art.”

Brian Belott’s installation “Dr. Kid President Jr. (2022),” one of three commissions reimagined for the exhibition from previous installations, centers on 26 works from the extensive collection of children’s art assembled by the early childhood educator Rhoda Kellogg and his own copies of some of them.

“Children have nonsense, they have free association, they have nonlinear thinking and non-narrative thinking,” he said. “They live in a fantasy and imaginary-driven existence.”

The son of two teachers of elementary school, Mr. Belott became fascinated with children’s art at a young age and started collecting works as a teenager. “There’s a godlike energy to them, a kind of fury, an outpouring; it’s unstoppable, it’s a force of nature,” he said.

He, like many artists, tries to reclaim a childlike mind-set, and “this primordial soup of ecstatic, creative energy that kids have an endless amount of,” in his own practice. “Children are actually brilliant artists, and adults should have confidence in their own self-exploring.”

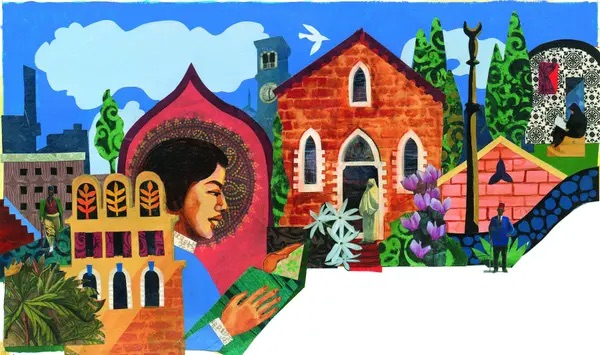

Ekua Holmes, “Bold Beirut,” from “Hope Is an Arrow” (2021). Ekua Holmes

The Page Is a World examines the world of children’s literature and artists’ contributions. “I love this idea of how artists interpret as children, for children, about children,” said Ekua Holmes, whose recent illustrations from “Hope Is an Arrow, ” a children’s biography of Kahlil Gibran, author of “The Prophet,” are featured. The story focuses on Gibran’s childhood in Boston after immigrating from Lebanon, his struggles to fit in in America, and being an artist and wanting to heal the world through his art.

“There is a pattern in many of the books that I’ve done,” Ms. Holmes said. “There’s someone or something that happens in that wet clay that we call childhood, some impression that stays and carries the person to this destiny.

“I remember from my own childhood, the feeling of being invisible to many adults. Who are the people who noticed you as a child, looked into your eyes, saw your gifts, and fostered your talents? What I want most is for children to feel seen.”

Born Into Being addresses agency, power, the complex ways that a child’s identity is formed, and how children are often marginalized. “I think children present a complicated test case for thinking about questions of power,” Dr. Erickson said.

Gestures of Care invites viewers to consider the visibility of all caretakers. It was easy to find images of mothers in the realms of art history and contemporary art, Dr. Erickson said, but “very challenging to find images of other kinds of caretakers, like fathers, domestic workers and nannies.” Jay Lynn Gomez, who created a large body of work featuring domestic workers, is represented with a piece titled “Nanny and Child.”

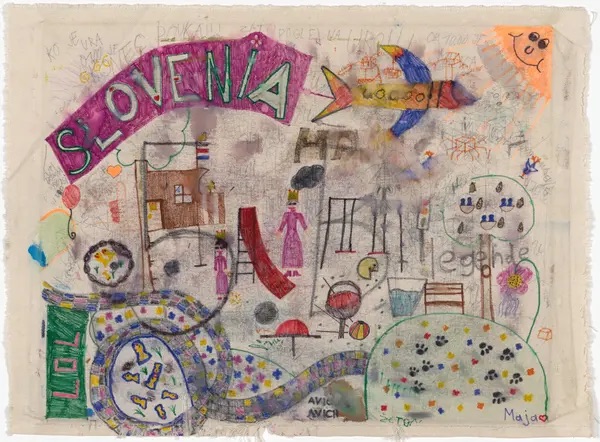

“Ljubljana, Slovenia” (2016) from Oscar Murillo’s “Frequencies,” a continuing project of artwork from schools in more than 30 countries. Oscar Murillo

After School highlights unexpected paths of learning. Featured are Carmen Winant’s new installation that assembles more than 300 instructional books written for young people on topics like how to deal with divorce or how to make handmade ceramics; and a selection from Oscar Murillo’s “Frequencies,” a continuing project of more than 40,000 works from schools in more than 30 countries, made by wrapping blank canvases around children’s desks and leaving them in place for a few months to create a space to be drawn and painted on.

The exhibition incorporates design and accessibility elements for children, like low-hanging artworks and age-appropriate wall labels so younger children can easily view and read them. It includes a reading room, an interactive drawing table where visitors can make their own works, and a series of special programs.

Anne Higonnet, an art history professor at Barnard College who specializes in the study of childhood, taught and took part in several seminars about the planning of the exhibition, including one with the institute.

“The belief in one particular kind of childhood was so strong for many, many decades,” Professor Higonnet said, “that it blinded art historians to any kind of analysis of the subject of childhood. We all just bought into a very particularly modern, European and upper-class definition.”

“‘To Begin Again’ includes artists who have pointed out the extreme range of childhood experiences,” she added, “artists who were not afraid to represent the anxieties, the fears, the ambivalences of childhood, and the socially, racially and economically unjust experiences.” But the curators, she said, “didn’t let go of all the positive things about childhood, like the marvelously open-minded and joyful aspects of a child’s imagination.”