- Source: Artsy

- Author: Emi Eleode

- Date: AUGUST 5, 2022

- Format: ONLINE

A “Fantastic” New Show Celebrates the Black Diaspora with Myth and Magic

Installation view of works by Nick Cave in “In the Black Fantastic” at Hayward Gallery, 2022. Photo by Zeinab Batchelor. Courtesy of Hayward Gallery.

In the Hayward Gallery exhibition “In the Black Fantastic,” Nick Cave’s powerful, newly commissioned installation takes center stage. The piece, entitled Chain Reaction, features hundreds of black cast-plaster arms—shaped from the artist’s own—joined together like chains. The hands grip each other as though trying to lift one another up. The installation touches on one of the show’s major themes: the legacy of slavery and colonialism.

Curated by Ekow Eshun, the exhibition features works by 11 artists: Nick Cave, Hew Locke, Kara Walker, Lina Iris Viktor, Chris Ofili, Rashaad Newsome, Wangechi Mutu, Sedrick Chisom, Cauleen Smith, Tabita Rezaire, and Ellen Gallagher. This is the U.K.’s first major presentation dedicated to the work of Black artists across the diaspora who use spirituality, myth, science fiction, and Afrofuturism to suggest utopian possibilities.

Installation view of works by Rashaad Newsome in “In the Black Fantastic” at Hayward Gallery, 2022. Photo by Zeinab Batchelor. Courtesy of Hayward Gallery.

The show also reflects challenges in our contemporary world, addressing racial injustice and issues of identity. “In the Black Fantastic” departs from a Western-centric perspective in order to explore Black autonomy and experience.

Eshun has cleverly divided the exhibition into separate rooms so that each artist exhibits within their own space; this makes it easier for the viewer to appreciate the individual artists, then analyze the cumulative power of the show as a whole.

Textiles feature prominently throughout. Some artists use diamanté (jeweled decoration), and Swarovski crystals glitter in the work of Rashaad Newsome. Multimedia pieces alternately feature wood, faux fur, beads, gold leaf, and sequins. These exuberant materials add a sense of vibrant diversity to the show, which also features painting, sculpture, video, mixed-media installation, and photography.

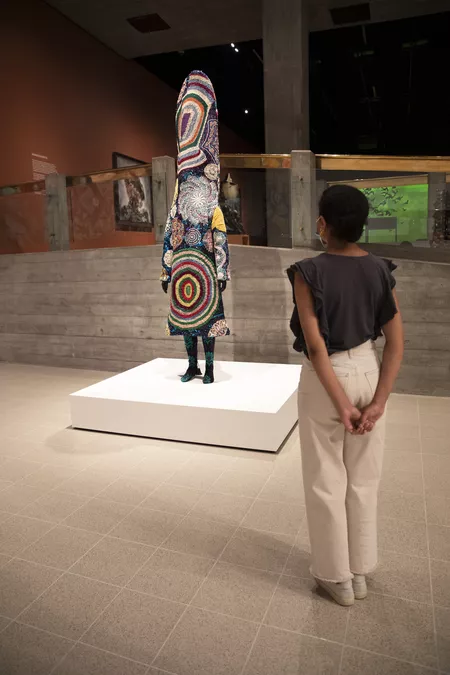

Nick Cave, installation view of Soundsuit, 2010, in “In the Black Fantastic” at Hayward Gallery, 2022. Photo by Zeinab Batchelor. Courtesy of Hayward Gallery.

Nick Cave, Soundsuit, 2014. © Nick Cave. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

In addition to showing Chain Reaction, Nick Cave also exhibits his famously colorful, bejeweled “Soundsuits,” which he makes with fabrics, embroidery, raffia, sequins, beads, and more. One features a West African masquerade look; it resembles a masked dancer with an elongated neck. Another comprises piles of knitted fabrics. Yet another looks like it hailed from the science-fiction realm, given its similarities to a suit that one might wear into space. Each Soundsuit is wearable and life-size.

Cave began making these costumes 30 years ago in response to the brutal beating of Rodney King by Los Angeles Police Department officers, which sparked the 1992 Los Angeles riots. The artist views the Soundsuits as bodily disguises and forms of armor that offer protection in a racialized society. Cave has also made a new Soundsuit that commemorates the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police. Despite their tragic inspirations, the works embrace ambiguity. They conceal the identity, race, and gender of their wearers with exuberant adornment.

Wangechi Mutu, still from The End of eating Everything, 2014. Courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery, and Victoria Miro. Commissioned by the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University.

Wangechi Mutu thinks about the body in a different way. Eshun has posted quotes from famous thinkers around the show, and Suzanne Césaire’s pairs perfectly with Mutu’s work: “Here are the poet, the painter and the artist presiding over the metamorphoses and the inversions of the world under the sign of hallucination and madness.” Throughout her installation, the Kenyan artist depicts the human body in mythical spaces and considers divine femininity.

Her collage The screamer island dreamer, for example, references nguvas, or water women, and a story about a female spirit who wanders along the coast. The spirit appears to be a regular human—until she charms people into the sea and drowns them. The piece evokes a surreal, satirical children’s storybook. “In the Black Fantastic” also features a video by Mutu and additional collages that combine magazine cutouts with natural materials such as shells, horns, and red soil from the artist’s travels.

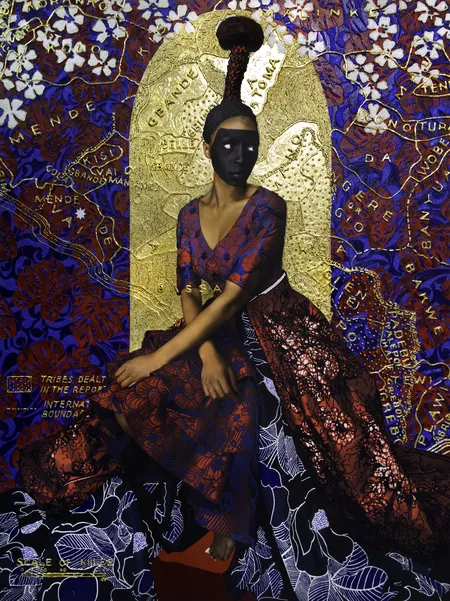

Lina Iris Viktor, Eleventh, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Hayward Gallery.

Hew Locke, Ambassador 1, 2021. © Hew Locke. Photo by Anna Arca. Courtesy of the artist and Hayward Gallery.

Throughout his colorful, mythical paintings, Chris Ofili reconsiders a sea spirit from a different tradition: The artist has illustrated a scene from Homer’s Odyssey, in which Odysseus encounters the island nymph Calypso. Ofili took inspiration from the Saint Lucian poet Derek Walcott, whose poem “Omeros” used characters from the Odyssey to analyze colonialism’s detrimental legacy. Ofili’s depictions of unearthly, underwater creatures introduce viewers to a magical version of the high seas.

Liberian British artist Lina Iris Viktor also transports viewers to a different place and time, though her vehicles of choice are bold mixed-media works. Her series of blue, white, and black self-portraits, titled “A Haven. A Hell. A Dream Deferred,” are powerful. One of them, entitled Eleventh, depicts the artist sitting regally, dressed in beautiful African textiles. Intricate gold lines trace a map, while partial texts that sprawl across the surface—such as “Tribes dealt in the report”—offer suggestive narratives. Viktor also paints the Libyan Sibyl, a prophetess from ancient Greek mythology whom 18th-century abolitionists considered to be a figurehead who foresaw “the terrible fate” of enslaved Africans. Viktor questions the role of Western altruism in the Republic of Liberia after the abolition of slavery; a colonial legacy still haunts the country.

Installation view of works by Hew Locke in “In the Black Fantastic” at Hayward Gallery, 2022. Photo by Rob Harris. Courtesy of Hayward Gallery.

Hew Locke uses sculptures to consider such legacies. His series of pieces, entitled “The Ambassadors,” resemble the horsemen of the apocalypse with their menacing postures. The artist has richly adorned his approximations of horsemen in fabric, beads, and other jewelry, then surrounded them with decorated skulls. “The Ambassadors” challenge how we view historical figures: The artist has embellished his four riders with military medals and regalia, which represent the heavy hand of colonialism.

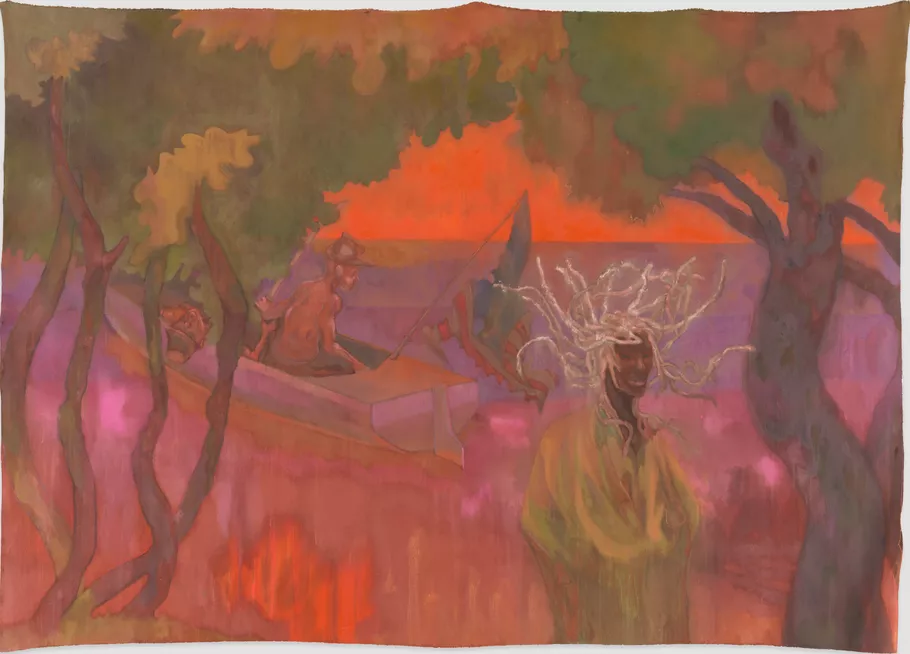

A sense of doom also pervades Sedrick Chisom’s dreamlike paintings. They feature characters who look deathly sick, suggesting a post-apocalyptic future in which all people of color have chosen to leave Earth, and the rest of humanity has been afflicted with a fictitious disease called “revitiligo,” which darkens the skin’s pigment.

Sedrick Chisom, Medusa Wandered the Wetlands of the Capital Citadel Undisturbed by Two Confederate Drifters Preoccupied by Poisonous Vapors that Stirred in the Night Air, 2021. © Sedrick Chisom. Photo by Mark Blower. Courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corrias.

Kara Walker, on the other hand, delves into America’s racist, bloody past throughout her cut-paper animations. Her violent, provocative subject matter will haunt viewers long after they leave the show. Walker’s film Prince McVeigh and the Turner Blasphemies (2021) portrays two white supremacist crimes: In 1988, three white men in Texas murdered James Byrd by dragging him to death from behind a pick-up truck, and in 1995, Timothy McVeigh bombed the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. The project’s title references The Turner Diaries by neo-Nazi leader William Luther Pierce, a racist novel that allegedly inspired McVeigh and other white supremacist attacks—including the recent January 6, 2021, assault on the U.S. Capitol. Like Chisom, Walker confronts the parasitic ideology of whiteness and the “othering” of Black people.

Rashaad Newsome’s work feels more futuristic, though it reflects on today’s chaos; Build or Destroy, his film in the show, might remind the viewer of the “this is fine” meme. The video shows a vogueing, trans CGI character dancing amidst fire and collapsing buildings. Sampling and reconfiguring visuals related to traditional African sculpture, the Black Queer community, and pop culture, Newsome hopes his work will help liberate us from oppressive systems.

Installation view of works by Cauleen Smith in “In the Black Fantastic” at Hayward Gallery, 2022. Photo by Zeinab Batchelor. Courtesy of Hayward Gallery.

Cauleen Smith uses digital systems to a very different effect. Her immersive installation features a table decorated with small sculptures, a bird, plants, and computer screens that project images of changing natural landscapes and enlarged digital versions of the sculptures onto the gallery walls. The artist has a personal connection to each item on the table. She describes the assortment as an “archive of associations, travels, affections, desires, questions, and longings.” Smith addresses themes of Afrofuturism, utopian possibilities, and community.

To conclude the exhibition, Ellen Gallagher’s fascinating painting Ecstatic Draught of Fishes depicts an underwater realm. The scene takes inspiration from the story of a Black Atlantis known as Drexciya, a place populated by the descendants of the kidnapped, enslaved pregnant women who were thrown overboard on transatlantic ships. The Drexciya myth was created by the eponymous Detroit electronic music duo, who were partly inspired by Paul Gilroy’s 1993 book The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Throughout Gallagher’s painting, brown amoeba with pink, orange, and dark purple circles form part of an underwater scene. Silver figures that resemble African sculptures float in the sea.

Altogether, these artists offer new ways of seeing and challenge the idea of race as a social construct. In their own unique ways, they reimagine possibilities for Black people the world over.