- Source: X-TRA

- Author: Candice Lin and Shana Lutker

- Date: Spring 2019

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

Conversation with Kandis Williams

INTERVIEW by Candice Lin and Shana Lutker

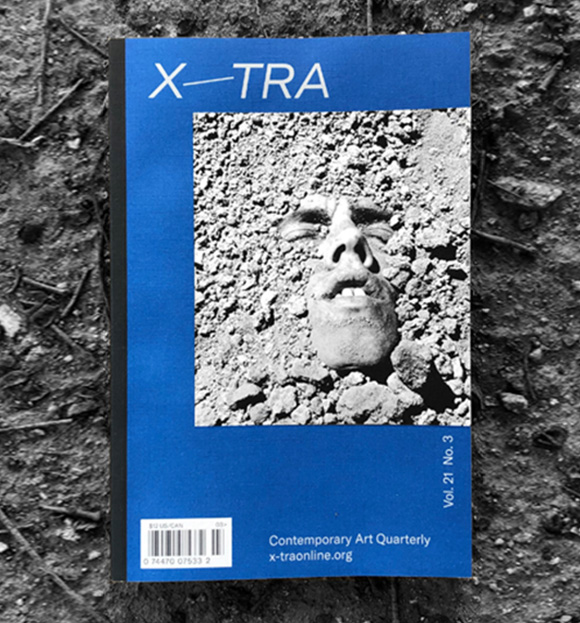

X-TRA, Spring 2019, Volume 21, Number 3

This conversation aims to give context to Kandis Williams’s artist’s project. The project’s imagery is drawn from The Rivers of Styxx, a body of work Williams exhibited at Cooper Cole gallery in Toronto, Canada, in the fall of 2018. Williams’s project in this issue, The Waters of Lethe, also includes a poem by Amy Fung, which was written in response to the Toronto exhibition and was presented by the gallery in lieu of a press release. The following conversation between Williams and X-TRA editors Candice Lin and Shana Lutker took place on November 3, 2018, and has been edited for print.

CANDICE LIN: Your images, particularly those including fashion models, seem to use Greco-Roman statues as a way to comment on the white-washed aesthetics of ideal beauty and the conflation of beauty with truth and by extension truth with whiteness. I was curious about your choice to include Naomi Campbell (and perhaps a few other models who are also black women) in the grouping of fashion models. Where there is the presence of one or two black fashion models in the images, it raises questions around what it means when blackness is paired with beauty while also being instrumentalized and held up as beauty/truth’s antithesis. These images, particularly the first image, in which you superimpose the face of a Roman sculpture over a model with an afro, made me think of Martin Bernal’s classic work Black Athena (1987). Bernal questioned the “Aryan model” of history and claimed that the racial origins of European civilization came from Afro-Asiatic roots. I know that Bernal’s work has been somewhat discredited and is contentious, but I bring it up because it questions a binary or anachronistic framing of Western civilization as “white,” and I interpreted what you were doing in your artist’s project as being a similar complication of a racial binary. Can you speak a little about that?

KANDIS WILLIAMS: Yes, I’m not thinking about race actually being a category of exclusion from the field of image production. More pointedly, the figuration of black bodies is not visually absent from any moment of Western history. I am thinking through sites of hybrid architecture or ruin, like the presence of Moorish architecture in Europe. One of the images is of Naomi and Iman perched on geometric architecture and tile work in Granada, Spain. I’m thinking about a confrontation between Islamic representation, a system devoid of figuration, as it confronts Western figuration that’s Christianized and sort of “white” (according to Sylvia Wynter). These sites were where the first logics of citizenship and race were starting to be constructed. The early metaphors around whiteness and virtue, or godliness, were manifested in the statuary deities with assigned human skin tones that flanked government buildings and meeting spaces. I’m interested in how the democracy of raced beings is posed through the confrontation of drastically different image cultures—abstract and figurative.

There are a few sources for the skull imagery in the project. There are recently found skulls from ancient Greece that are of African origin. I’m thinking about the debates on the origin of man, and how skulls are used to spark or spur racebased thinking and act as proof of racial identity and as trophies of genocide and holocaust. Given the amount of migration, trade, and conquest during the Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic periods—and evidenced through the epics and historical narratives of the Peloponnesian War—Proto-Greek pantheistic governance was radically changed during the birth of African colonialism. I’m interested in how that changed the utility and function of Greek myth from phenomenological to grounded theories of governing. The African skulls are from Namibia. In 2018, they were returned to the Namibian government, from the German universities who had had them since the genocide of the Herero and Namaqua tribes. The morbid United Nations-mediated funerary ceremony was widely publicized almost as a moment of reconciliation. These skulls, as well as the ones found in Greece, also reference this strange marking of place and debates in migration initiated by colonialism and nationalism.

LIN: This brings to mind Achille Mbembe’s idea of necropolitics and how his work tries to revise a history of the biopolitical, as beginning not with the concentration camp of the Nazi Holocaust, as Giorgio Agamben writes of it, but instead with the plantation. It’s interesting to me that you would choose the images of the Herero and Namaqua Genocide, which was perpetrated by the German colonialists in the early twentieth century (in present-day Namibia). These murders and atrocities took place in a concentration camp that existed before the Nazi Holocaust—which is our Westernized historical symbol of what “concentration camp” and “holocaust” mean. By using this example, you show how the biopolitical is tied to race, which Agamben tries to avoid.

WILLIAMS: It’s the first bureaucratized holocaust. It’s how the Germans learned the formulas for the death camps of the Nazi Holocaust. There are so many levels of racialization there. I’m also thinking of the idea of Plato’s cave as a proto-holocaust, like a proto-idea of the necessity of the kind of governance that enables so many of the ideologies that support slavery. The cave becomes the first justification or relief of the burden of being inhumane and the inevitability of slave holding. Before, the cave was a symbol of the moment when everyone is equalized in death. All the stories before Plato’s cave are about this inevitable journey of heroes into their own self-obliteration, into their own willingness to join everyone else in death. I don’t think the theory of the cave is racially reducible, but there is now a more discernible difference between phenomenology and ethnography, and we can look ethnographically at the founders of these categories of thought.

LIN: I was wondering about the question of time in your work. Here, for example, you collage together fashion photos from the nineties with Greek and Roman sculpture and images of severed heads from the Herero and Namaqua Genocide. I was wondering if you were drawing a spectrum or lineage of histories and types of racialized violence?

WILLIAMS: Yes, exactly that. Drawing them all into the same picture plane for me is making really direct textual analogies. A lot of the open-sky shots are from Romanized Western Britain, sacred sites to the Celts and the Gaelic tribes that were wiped out by the Romans in the first century. Going back to that earlier point, I’m thinking about the cave as a phenomenon of governance where race is a carrier that’s not necessarily phenotypically specific but ideologically mandated. The highly matriarchal or non-centrally led tribes of all of Western Europe were brutally colonized for reasons of control, of governance. I’m thinking about spaces and cultures that have been erased, and what their place or space holds, or ruins hold. That’s why I used a lot of the sites on both sides, in Greece and Northern Africa, that were ruins of temples to Bacchus/Dionysus. In the Platonic revolution, he goes from being a god of harvest to a god of conquest. He ultimately becomes the god of conquest and intoxication. There are cults to Dionysus all over Northern Africa from around the time of the Peloponnesian War. I see these sites as places where the birth of democratic governance was first intentionally rooted in difference and, at that time, was not exclusively racialized. The Aeneid was one of the first stories of the topsy-turvy relationship between Africa and Greece as it transitioned to Roman superpower. Values of conquest and rape culture are concealed within myths of tragic romance—Venus is Aeneas’s mother. In the narratives about Aphrodite/Venus and in the stories about Zeus’s acts of rape and Hera/Juno’s rage, there are so many ways in which a lot of these acts of violence are consumed into narratives of the power of familial inheritance, illicit reproduction, and their importance to the births of heroes, kings, and nations.

I’m also thinking a lot about reproduction and ideas of beauty, how images produce thoughts, how thoughts produce images, and how thoughts produce words and undo meaning. I’ve been thinking about reproduction via the three figures—the Lover, the Artist, and the Fetishist. Physical sexual love and intimacy reproduce certain values, and metaphorical languages—metaphors around reproduction, physical love, and sexual love—end up obscuring or erasing the agency of the maternal to govern or protect life, another way that patriarchy has grown from an index and symbology concealing the nature of reproductive oppression inherent to rape culture and conquest culture.

SHANA LUTKER: Why did you choose fashion images from the nineties? To me, it feels personal, a nod to that moment when, as young girls, our first ideas about beauty were being shaped by these images that were circulating everywhere.

WILLIAMS: Yes, these images from the nineties are definitely personally triggering. I was born in 1985, so by 1995, I was very aware of those groups of figures in silhouette—Reaganomics, United Colors of Benetton, and the birth of neoliberal, non-race-based “colorblind” aesthetics, where there’s one black girl, so it’s all good. Everyone else is brown-haired or blonde. They were also speaking to me in terms of how much the compositions share with Roman funerary coffins, which would represent everyone in the dead person’s family. And I’m thinking about early colonial photography, how it looks to include the trophy body: compositions of people’s bodies, as trophies, as hunted creatures.

I think that those nineties models epitomize everything from the Victorian woman in painting to dolls of the Rococo—they are modeling (embodying) modes of feminine figuration in every season. They’re in all of these very extremely aestheticized painting spaces, and they lay the groundwork for neoliberal inclusion. The logic of these advertisements felt like governing principles of sexual desirability. They resonate as Apple ads for me, they resonate as a really good screen saver, as product placement. I guess I’m kind of laughing to myself thinking about decoratively painted Greco-Roman sculptures looking to ancient eyes like these Benetton ads do to us—that distribution of mostly white skin tones with a few pointedly political black skin tones wearing cute clothes from all over the empire.

LIN: I’m interested in what you’re saying about the extremely aestheticized Victorian women, paintings, and the burial coffins from Rome. I am curious about your choice to superimpose skulls on their faces and the reappearing imagery of the skull. I think of the skull as being this loaded object, from its history of being used as the physical “proof” of a lot of racist science. I believe even some of those severed heads from the Herero and Namaqua Genocide actually were sent back to Europe and studied for that purpose. I am wondering what is at stake for you in the use of the skull and this aestheticization of death, in relationship to blackness or this history of violence that’s perpetrated in a racial way. From what I was hearing you say earlier, that is only part of what you’re interested in. But are you also drawing a broader history of the ideology of imperial conquests?

WILLIAMS: I’m thinking about conquest and control, so yes, necropolitics. Also the mythological aspect of death—what it means to die to people before empire, and after. There’s not really much at stake for me personally in using those images of skulls. Emotionally, I feel numb to most images of black death or dead—I expect them too much. I think they’re images that are used for control, they’re flatly images that are just used. They’re the evidence of murder, of genocide—as much as of triumph and progress. They evidence the birth of the republic we live in now—and the life lost to its formation. The thought of not having a rightful place in death because your skull is kept as a trophy is an old fear. Differences in the funerary treatment are the only way to understand and represent lives that could be controlled, lives that could be prematurely ended.

LIN: It’s interesting that the skull is the proof of the genocide but also the object used to justify it.

WILLIAMS: Right. Going back to what’s at stake for representing black death, I don’t feel any ownership over images of black death because there’s not a black person behind those cameras. In so many ways, I don’t want to deal with the fallout of what it is to have taken a photograph of, for example, a mound of skulls (one of the famous images of the Herero and Namaqua Genocide). Standing next to a pile of thousands of skulls is a German officer. Germany or its folk have to answer for that image. Those images were taken by colonists and included in national archives by non-black people—I believe in order to terrorize future black-appearing people. For me, the evidence of the skull itself, and the questions it raises (has it been traded or given back, studied or buried, washed and wrapped?) is really interesting today. The African skulls from ancient Greece, which are not being given back to Eritrea or Ethiopia, are still fully deep in politicization because today we (black/genocide survivors/colonized people) are talking about who owns black death. Skulls raise the question of who is able to rest, as a political body or not, who is granted the ability to rest in death or rejoin the human whole. I’m thinking around that, in spirals.

LIN: I was reading something that you said in an interview with Cayal Unger.[1] Unger was talking about your use of compositional fragmentation as a strategy to disrupt or complicate consumption of representations of blackness. I don’t know if you agree with Unger’s interpretation. In this project for X-TRA, you make visible a lot of photographic technologies, like superimposition; the purposeful distortion of the images, which are stretched to fit the format of the journal; and the visible pixelation. And these images are also all cropped details of your exhibition at Cooper Cole. Can you talk about these choices?

WILLIAMS: I used to be really interested in dissolving photographic content, of taking a photograph of a politically significant moment and destroying its photographic significance through collage—cutting into things, fragmenting things, and inserting other things. But now I’m more interested in the meta layers of image production. I think my practice has changed in the last two years from that deconstruction of images to now, where I mostly just leave the image. The layers of the production of the image are more what I’m into; I don’t have to intervene so much in the actual image. I want how and why it was made to share the scopic space. It’s more about putting images next to each other or letting them occupy the same arena, as what they are. I’m really into letting the seams be seen for that reason. If I get the images from a website, I’ll leave the website name on the image. If they’re pixelated images that I can’t find large enough or if I can’t scan them from books—if I can’t find them the way that I want them—then I’ll print them the way I find them, and let the manipulation be seen in the image. I just want as little obscuring as possible, letting the collage look very obvious as data to the viewer. It’s really important to me right now. I want a roughness even if there’s a material slickness.

LUTKER: It seems that this shift from collage by cutting and abstraction to translucency, layering, and blending is also, at least in part, driven by the theoretical frameworks that you’ve taken up.

WILLIAMS: I’m trying to think about why that change happened, and I feel like it’s linked back to the politics and stakes of representing the black body. I think as a black person, making work in Germany for nine years, I had the opportunity to really get into archives that I liked or was curious about, to really ruminate on images that I was very personally interested in. And I think here, in the last two or three years, I’m being called on as an artist to produce something political for markets and institutions but for my peers as well. I’m being asked to respond to the re-emergence of nationalism and fascism. The age that we are in is about how fast we’re able to share these images of atrocity and link them to information previously largely repressed on platforms widely surveilled but without the reins to vet most content. Before, it was more of a niche. I did a series of collages 10 years ago with the Jonestown massacre, and I would have studio visits where people would be like, “You’re a crazy person for looking at these pictures. What about cool black people? Like pictures of cool black people?”

I used to love looking at awful images, you know what I mean? As a kid, I made horror movies and would dig up dead pets. It took me years to understand how growing up in poverty and with abuse had desensitized me quite young to seeing dead people—dead black people. The fictional space of horror felt like a relief from the standard systemic violence we knew every day.

I feel now like I’m using that tuning—of being able to look for a long time at terrible things—to look at mainstream image production and the horror of these “normative” narratives. I used to be really into the obscurity of images and obscure archives, images that no one had seen. Now it’s the images that everyone is looking at that are interesting to me. And that’s weird and feels less aesthetically rewarding. I have so many pictures of Kim Kardashian, I don’t even know what to do with her face.

Right now, it’s interesting to be in a dialogue about these fashion images and understand more intensely why they’re mandated, why people rally behind them, how people live and construct self through them. Why they are so delectable somehow to a popular audience, why they are so consumable, and why they still operate, as in Fred Moten’s “Resistance of the Object: Aunt Hester’s Scream.”[2] I’ve been back and forth about it; I’ve always understood how fetishistically images of black bodies are consumed. There is this question of Naomi [Campbell], for me, as a person whose body and its visibility I’m told has made the world easier to live in. Yet I know to look like her in this culture is to be constantly accused of prostitution and considered sexually so available that one is both un-rape-able and so penetrable that one is invulnerable to violence. There’s this question of Iman, like there is the question of Renee Cox, of Kara Walker, of Adrian Piper, of the black female artist who’s willing to be nude, or willing to be hyper-vulnerable, or willing to be a part of this really intense fetish image culture. If there is power in those images for some young women and propaganda for the control of other young women, what is clear is that there is a market and discourse for these questions that is far greater than the cultural capital that is moving toward the reparative justice to correct racial inequalities.

LIN: How do you position your art and yourself in that? When people are really eager to consume these images, are you actively always thinking about, “How do I make an image that might have a kind of fetishism to it but is also Aunt Hester’s Scream?” Something that has the kind of resistance or moment of break in it? Or, are you trying to let it be what it is, and if it’s consumed, that’s fine?

WILLIAMS: It goes back and forth. My position is plural. I don’t think anyone’s position is binary, ever, actually. My position is plural in terms of the demands of the market. My position is plural in terms of a discourse that I want to be a part of, or I don’t want to be a part of. Taking on a popular black moral position or not is always a question, and sometimes a pain in the ass. But I am very thankful for the “black chattering class,” as Adolph Reed puts it, and to be in proximity, to have community there.[3] But my position is plural, and always has been.

I don’t know any way that my work has been consumed that I’m totally cool with, to be honest. I feel like that’s another weird area where these binaries and systems push responsibility and accountability onto the oppressed subject. I’m really aware of having to hyper-evidence my everything: “I didn’t manipulate this or that. I know where this source came from. I made this myself.” That’s one of the most painful but relatable elements of Adrian Piper’s recent retrospective at MoMA and the Hammer. There are so many different things that black femmes have to hyper-evidence constantly to avoid the dominant suspicions and assumptions of our positions on everything in public and in private. And I’m really resentful of that, I guess, just flat out. I don’t think it is the job of the artist to give evidence of their intentions in every work. I don’t like providing evidence with an image I make, from my experience, lived or static. I see a lot of people really rejoicing in archives of blackness, and for me, they’ve always been contentious places where I worry about authorship and I wonder about propaganda. Because appearing black and being black—having so much dialectic power within image culture—I don’t think that any “picture” of “blackness” is ethnographically reducible anymore. The images now contain the phenomena of their production.

Candice Lin is an interdisciplinary artist who works with installation, drawing, video, and living materials and processes, such as mold, mushrooms, bacteria, fermentation, and stains. Lin has had recent solo exhibitions at Portikus, Frankfurt; Bétonsalon, Paris; and Gasworks, London. Lin is a member of X-TRA’s Editorial Board.

Shana Lutker is an interdisciplinary artist whose work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden and Pérez Art Museum Miami. Lutker is the Executive Director of Project X and a member of X-TRA’s Editorial Board.

[1] Cayal Unger, “Theory and Experience in the Work of Kandis Williams: Cutting Edge Dissociation,” Artillery, January 2, 2018, https://artillerymag.com/theory-experience-work-kandis-williams/.

[2] Fred Moten, “Resistance of the Object: Aunt Hester’s Scream,” In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press), 1–24.

[3] See Adolph Reed, “The Trouble with Uplift,” The Baffler 41 (September 2018), https://thebaffler.com/salvos/the-trouble-with-uplift-reed.