- Source: X-TRA

- Author: Gracie Hadland

- Date: November 23, 2021

- Format: Digital

The Relationship Trade

—

The Dash column explores art and its social contexts. The dash separates and the dash joins, it pauses and it moves along. The dash is where the viewer comes to terms with what they’ve seen. Here, writer and curator Gracie Hadland explores her relationship to the relationships condensed in SoiL Thornton’s exhibition at Morán Morán in Los Angeles, on view August 21–September 11, 2021.

SoiL Thornton, Bench/barrier (314 lbs), 2021. Aluminum foil and aluminum foil tape compressed to the combined weight of momma and deddy, 29 x 25 x 16 in. Installation view, My Child will be named after me, Invasive, or was it Prayer? I need to check my notes., Morán Morán, Los Angeles, August 21–September 11, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Morán Morán.

Last month in Copenhagen, I overheard two men, one American and one Italian, talking about laundering money. The American spoke about moving money between accounts and how he planned to avoid being audited. Naturally, the conversation turned to art: a mention of the singularity of the Mona Lisa, then the Italian began to explain NFTs, or non-fungible tokens. The American had trouble understanding their value. How is one unique? If I can’t hold it, how do I know its worth? He used gold as an example. “Gold, I know, is valuable because I can feel it in my hand and it’s heavy.”

In SoiL Thornton’s solo exhibition at Morán Morán, the artist examined the (im)materiality of money and labor, the transactional nature inherent in relationships. The exhibition was the first in the gallery’s new space, which shares a parking lot with the Arco station on Melrose and Western. Originally OHWOW gallery, located in West Hollywood, run by Mills Morán and Aaron Bondaroff, it became Morán Morán after Bondaroff resigned following several allegations of sexual misconduct. Many of these reported encounters occurred in quasi-professional contexts in which Bondaroff abused his power and influence to take advantage of women. Perhaps unwittingly, the exhibition, in addressing the monied, powerful, masculine nature of the art world, critiqued the very context in which it appeared.

SoiL Thornton, 101 impressions (people crush)(it takes a village), 2021. Aluminum foil, plastic, paper, ink, colored pencil and graphite on paper with tape, dimensions variable. Installation view, My Child will be named after me, Invasive, or was it Prayer? I need to check my notes., Morán Morán, Los Angeles, August 21–September 11, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Morán Morán.

Thornton has a deep awareness of the gallery’s operations and their role in revealing aspects one might not consider otherwise. When I visited the gallery, the directors were in the other room loudly Zooming with their bookie, declaring large sums of money. I thought it was an audio track in the exhibition at first. A man from a shipping company came in holding an invoice in one hand, resting the other on one of the works, Bench/barrier (314lb) (2021), a 314-pound ball of aluminum foil which sits just in front of the entrance to the main gallery space. One must maneuver around it to enter. The directors and the shipper shouted across the artwork from different corners of the gallery. The ball of aluminum foil, which presumably required hours and hours of manual labor, acted as its name suggested as both bench and barrier.

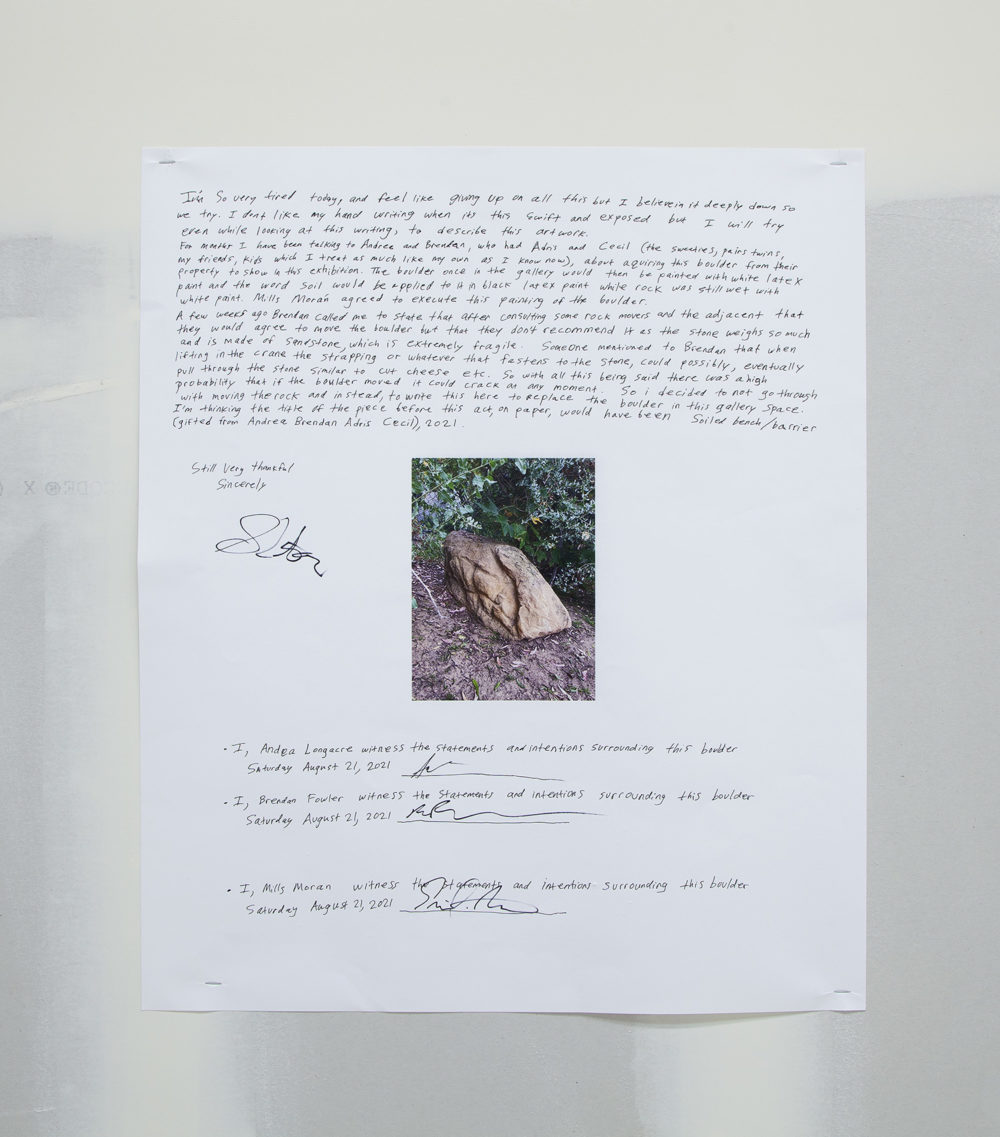

SoiL Thornton, Familial letter, 2021. Inkjet print and ink on paper, 24 x 20 in. Installation view, My Child will be named after me, Invasive, or was it Prayer? I need to check my notes., Morán Morán, Los Angeles, August 21–September 11, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Morán Morán.

Labor in the art world is often either totally obscured, behind the scenes in storage or in transit—or overly performed, in the artwork itself or socially among its participants. Thornton’s installation was quite sparse save for blue and pink hamster balls scattered on the floor. For the work, 101 Impressions (people crush)(it takes a village) (2021), the artist employed the labor of their friends, each of whom crumpled aluminum foil into a ball and sent it to them. The balls are each labeled with the friend’s first name on a piece of paper crudely applied with tape. The artist themself made the 314-pound ball, which took months of wrapping and wrapping foil. I imagine the artist in their studio beginning with a tiny ball of foil, the kind one might fidget with in an anxious moment—that anxious moment becoming a massive physical object, a kind of Sisyphean boulder. The invisible labor of the friends in 101 Impressions is stark in contrast to the heft of the object the artist themself produced. It’s as if Thornton subsumes the labor of their friends and displays it in physical form, as if one were to combine all the small balls of aluminum foil one would get the boulder-sized aluminum foil ball. Or it suggests the opposite gesture, dispersion, as if it had exploded, leaving a smattering of pieces of itself. The boulder is a physical manifestation of time and obsession only to be rendered in a material essentially worthless (aluminum foil) yet artistically valuable and financially an asset (art in a commercial gallery), while the relatively inexpensive metal (as opposed to, say, bronze) subverts its supposed value in the art market. The value, then, is in the artist’s own activity. The American man in Copenhagen mentioned above might have a hard time understanding the full value of this foil boulder, even if it is heavy and made of metal.

SoiL Thornton, Every piggy grows into bonds if it eats stock (hopes expansion and contraction), 2017–2021. BLESS Piggybank chair (wood, plastic, and wicker), saved and found coins and aluminum coin shapes, gifted and saved change from momma, and tape, 40½ x 19 x 18 in. Installation view, My Child will be named after me, Invasive, or was it Prayer? I need to check my notes., Morán Morán, Los Angeles, August 21–September 11, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Morán Morán.

Familial Letter (2021), a large handwritten letter tacked to the wall, details the failure of a work’s production, which then became the work itself. Initially, the artist planned to acquire a sandstone boulder from a friend’s property and have it installed at the gallery where the gallerist, Mills Morán, would paint on it the word, Soil. After consulting shippers, the boulder’s transportation was not recommended due to its weight and the fragility of the rock. The boulder was not shipped, but a photograph of it is pasted on the letter above the signatures of the people involved. The fragility of the boulder takes on a poignancy accompanied by the artist’s declaration that begins the letter: “I’m so very tired today and I feel like giving up on all this.” This phrase reveals a kind of fragility with which the entire exhibition was constructed, seemingly a challenging and laborious process that relied on the support of others.

Throughout the exhibition, Thornton employed various methods of analog circulation: mail, shipping, currency. The foil balls in 101 Impressions (people crush)(it takes a village) have had separate private lives in transport, arriving in boxes and packages and envelopes. The work has gone through an obscure transformation, unseen by others, accumulating in a liminal space between makers, between Thornton and their friends. Facing the wall in the second gallery was Every piggy grows into a bond if it eats stock (hopes expansion and contraction) (2017–2021), a chair with broken caning, as if someone smashed her foot through the seat or sat down too hard. The legs of the chair are made of plastic filled with coins in various currencies. The coins in the legs of the chair have ostensibly had their lives in circulation, too. I think of the Cildo Meireles work Inserções em circuitos ideológicos 2: Projeto Cédula (1970), in which the artist involved the system of circulating money to disseminate political messages stamped on Brazilian banknotes.

SoiL Thornton, Flagged Identity (2), 2021. Archival pigment prints of my active and inactive bank card chips, found photos, mirror finished stainless steel and white gold leaf frame, 49¾ x 48¼ x 2¼ in. Installation view, My Child will be named after me, Invasive, or was it Prayer? I need to check my notes., Morán Morán, Los Angeles, August 21–September 11, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Morán Morán.

There was a coin shortage in the United States this year. I went to several establishments that did not accept cash, which disturbed me, not only because of its classist implications, but because of the anonymity that is lost with “cashless” transactions. Another series by Thornton called Flagged Identity (2021) uses archival pigment prints of the artist’s active and inactive bank chips, perhaps teasing the expectation that an artist’s work must identify them. The walls of the gallery were left unfinished, unpainted; this was also a kind of not-work for sale as a work, titled In highest preparation for becoming (2021). The unfinished paint job again suggests the revelation of concealed labor; perhaps the preps got to go home early. Employing these defunct materials, waning in value—coins, inactive bank chips, aluminum foil, an unfinished paint job—the artist further abstracts the material value of their own artwork.

For the past year, I’ve worked for a gallery, watching how the sausage is made. There is nothing that makes one more aware of the collapsing space between money and art. Nothing makes me less interested in art. And nothing makes me more excited about art than someone like Thornton who is interested in making work that reaches beyond the gallery, that involves those outside of it, and examines the connections made through, or despite, these systems of circulation.

X—

Gracie Hadland is a writer living in Los Angeles.