- Source: Bomb Magazine

- Author: Verne Dawson

- Date: July 15, 2017

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

John Giorno

by Verne Dawson

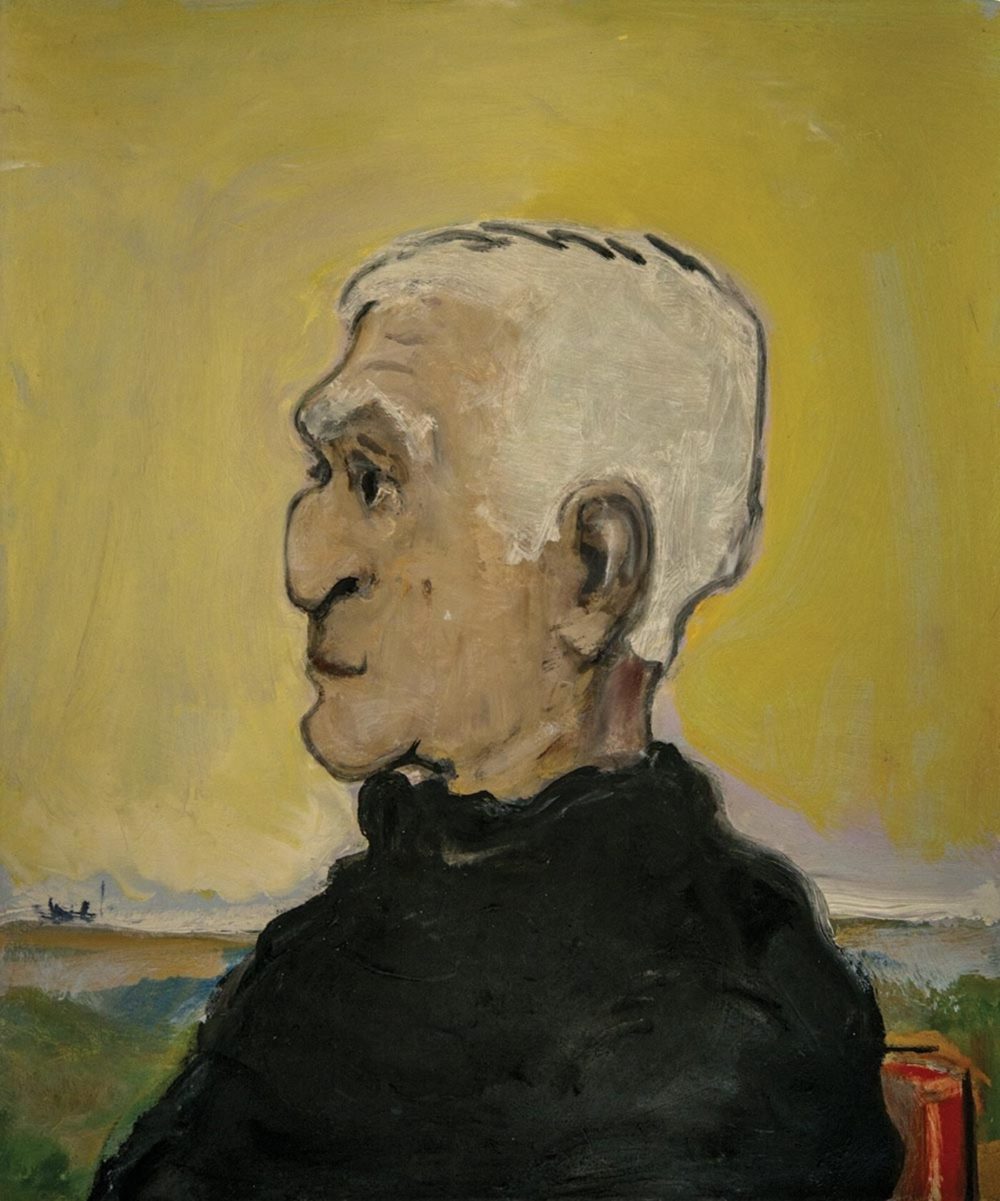

When I asked my friend John Giorno to sit for a portrait in 2003, his answer was yes. Situated in a comfortable old wicker chair with a purple and green floral cushion, he was looking out a glass door onto a small apple orchard. It was summer. Two hours passed. Five years passed. It was autumn. Asked if he was tired, if he needed a break, the answer was no, he was fine, and happy to sit longer. After five hours it was I who said that we should quit for the day and join the others for dinner. We resumed the next day. And again two weeks later. Never a complaint, not a single sigh from the model. John has a lot of room in his head to wander. Ten years later, I’m painting his portrait on the same canvas. One might say of John that it is his repose and never his pose that makes him the ideal model. Oh, and the fact that he will return after two years and sit again so I can make an adjustment to an eyebrow or his jaw line. He has been paler, tanner, younger, older, on a background of blue sky, then an ochre wall, with plants, without plants, with plants again, and so on. Could I possibly be finished? No, not at all.

This spring, I went to visit John at 222 Bowery where he has lived and worked since 1965. We talked like we’ve talked so many times over the past twenty years—except this time, our conversation was recorded.

—Verne Dawson

Verne Dawson, Portrait of John Giorno (2003–17), oil on canvas, 24 × 20 inches.

VERNE DAWSON

I’ve been reading your new poem.

JOHN GIORNO

”Wish-Fulfilling Jewels & the Poet.”

VD

It’s really beautiful. It’s strange for me to read it because I’m used to hearing you perform your poems.

JG

This one I haven’t performed yet. It’s a fable-style poem. I started writing those around the year 2000. In those days, I liked taking long train rides in Europe, first class, smoking joints in the toilet—between Paris, Zürich, Amsterdam, wherever. I really wished that I could write a fable and that longing lingered for days and weeks. Then, all of a sudden, I had written my first fable. Seventeen years later, I’ve done seven of them. And every time I write one, I say, “This is my last fable.” (laughter) You know, I’m a poet.

VD

It brings a lot of different cultures and even fable traditions into its own fable-ness, doesn’t it?

JG

I never went back to investigate the fable. Whatever I learned sixty or seventy years ago is what I know. I was enchanted by fables in my early teens, by the Grimm tales and all those. I’m not writing traditional fables, they just come nonverbally through my mind, and that’s how I get there.

VD

The poem is about reincarnation in some measure, right?

JG

Well no, not at all. Being a Tibetan Buddhist meditator for fifty years, the practice has transformed my mind, but the idea of that poem arose from being fascinated by old jewels. The thought that jewels have these lifetimes, involving the people who owned them, and that a person’s karma remains in the jewel, made me want to write about them. I’ve been going to Italy for more than sixty years. In southern Italy—my family is from Basilicata and Puglia—I got the idea for the poem. My father’s side of the family can be traced back to eleventh-century Norman barons. Rosanna, a researcher, traced my ancestry in the thirteenth century to an ancient great-grandfather, whose brother was a priest. I went to his church, a Romanist church. I stood where the priest stood and did my meditation practice. It was probably a catastrophe being a priest in 1280, 1290, or 1310—the chaos of medieval times and all the suffering of the people. I’m a performer, so I felt an affinity to his role. I was shown the priest’s thirteenth-century manuscripts, and I touched his signature. I asked researchers what he would have worn? Did he wear brown monk’s clothes? I was told, “Not at all.” All of that was part of the genesis of my poem and the priest’s bejeweled clothing—

VD

Castoffs from the aristocracy—

JG

The researcher described it as a competitive ritual—the noblewomen fought with each other over who would give the best clothes and jewels to the priests. Noblewomen’s clothes and priest vestments were quite similar. The jewels were sewn onto the priest’s bib. In medieval Roman Catholicism, these spectacular extravagances were similar to those of a rock star. They gave people joy. There were pageants, reenactments, early plays, and all these things in the church. Having the ability to mount a rock concert was key to the church’s success. So my ancestor had to participate in this, and that’s why the garments were so extravagant. Why am I saying this?

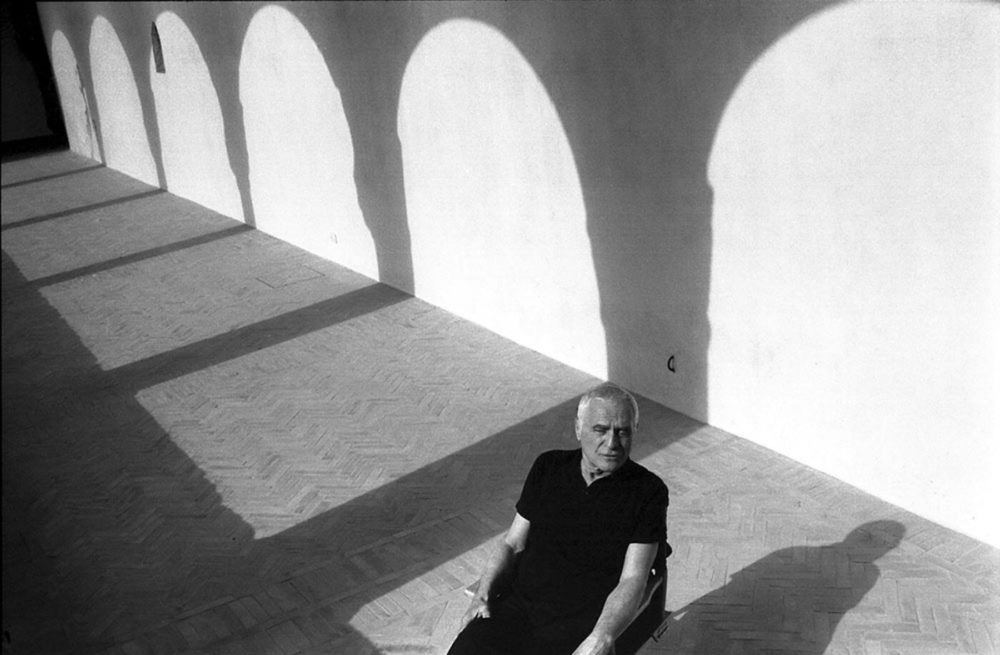

Giorno during the filming of Nine Poems in Basilicata, Montescaglioso, Italy, 2007. Photo by Salvatore Laurenzana.

VD

I was asking about reincarnation—in this case, it’s a thirteenth-century priest.

JG

Well, it’s in my roots. There are memories in the DNA. I come from a family with priests in every generation. Because the eldest son inherited everything, and the other sons—if they didn’t marry an heiress—had to become priests because they didn’t inherit anything. I’m sure some of them were good priests who were meditators, like me. So in the poem, I made this ancient uncle of mine into a serious meditator.

VD

And the specific histories that you recount of these jewels—are they fabricated?

JG

Yeah, they are fabricated. I invented the “diamond with the king inside,” but it could be the Hope Diamond in the Smithsonian. The ancient Buddhist Queen and the Blood of the Virgin Ruby are all real. I’m paraphrasing.

VD

When you look at the world or at history, what is divine or divinity? To you, I mean.

JG

Divine implies God, and as a Buddhist, I believe God is man-made. All of us have invented God. Trying to explain a primordial state, the empty true nature of mind, men invented God in their own image. So the divine takes on characteristics that are a mix between men’s cultural identity and certain aspects in spiritual realization that are recognized, like bliss and clarity. These then get interpreted in different ways, many quite distorted by each religion.

VD

Did you go to mass on Sundays when you were growing up?

JG

No, not at all. My father was born in 1901 and my mother in 1910, and in the ’40s and ’50s, they were the type of Italian Americans who only went to church on Thanksgiving, Easter, and Christmas.

VD

You were never an altar boy?

JG

No. My mother was a fashion designer, and I had a nanny who took care of me when my mother worked. The nanny was Irish Catholic and she made me kneel down in the morning and say, “Our father who art in heaven…” I hated doing that, so finally I got up enough nerve to tell my parents, “She makes me say these prayers, and I don’t want to say them.” My father said, “Well we didn’t ask you to say them. We’ll tell her to not make you do that.” And that was it. Later, when they got to their seventies and eighties, my parents went on to become Roman Catholics.

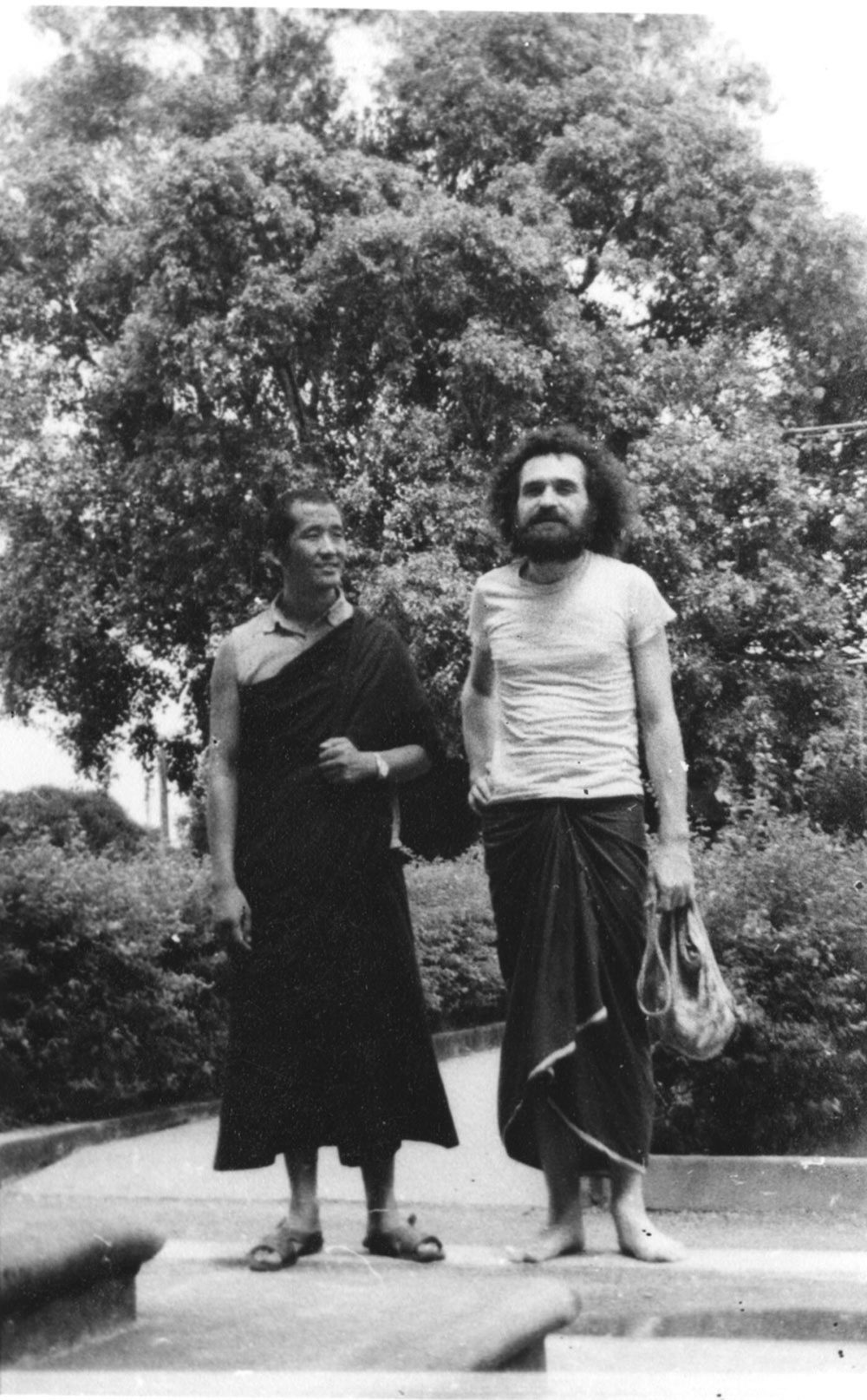

Nyichang Rinpoche and Giorno in India, 1971.

VD

So if you’d been an altar boy, even briefly, your story could have been very different.

JG

It’s not a correct thing to say, but I’ve always known I was gay.

VD

Why is that not correct?

JG

I often thought to myself that I wanted to make it with the handsome priest, knowing that I was gay, even at twelve, but not quite knowing what sex was. If I had made it with a priest, I hope I would not think it sexual abuse now, because I wanted it.

VD

Oh gosh. I don’t know. I didn’t grow up in a religious household either, but if there was anything to go to, it would have been a pretty austere Protestant function.

JG

The Protestant rituals are as nonspiritual as the Roman Catholics’. Born servants, all these restrictions and the don’t-dos.

VD

Brilliant people still turned to Catholicism. I’m thinking of writers like Graham Greene or Walker Percy.

JG

T. S. Eliot.

VD

Yeah.

JG

Well they were in need of making something spiritual happen in their life, so that’s the invention they chose. I think they were more comfortable with the Roman Catholic Church, which was more political than the Church of England. They joined a powerful political organization.

VD

I remember that recently we talked about early influences and how Eliot was important to you.

JG

He was really important to me because I wasn’t exposed to poetry until I was thirteen years old. I went to a great high school in Brooklyn where they taught The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock and The Waste Land. Both are such great poems and they were enormous influences on me. I went to James Madison High School from 1950 to ‘54. Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the Supreme Court justice, graduated from there in 1949, the year before I entered. She had the same brilliant English teachers who changed my life—Deborah Tannenbaum and Philip Rodman. Senator Bernie Sanders, the presidential candidate, entered James Madison High School in 1956. I can see how Bernie Sanders’s mind was formed, as mine was, by those teachers. By the time I graduated I had learned everything about literature from the beginning up until that moment, which was before the Beats, before William Burroughs.

VD

Eliot brings such a contemporary view of the world. It must have been unusual to encounter that at the time.

JG

I went on to become a Buddhist, and Prufrock seemed like a Buddhist. Eliot was handing out a basic Buddhist poem, you know. Or The Waste Land—

VD

When I worked at a library in Alabama as a teenager, they would discard LPs when they got scratches on them, and I got Eliot’s Four Quartets that I’d play on my turntable back home. It was one of my favorite things of all time. I never thought of it in a Buddhist context. Interesting.

JG

The poetry at that time was W. H. Auden, Eliot, and Pound. I was fourteen or something when my English teacher, Deborah Tannenbaum, said, “Dylan Thomas is performing this coming Saturday, and you should all go there.” I went by myself to the YMCA where Dylan Thomas performed with six actors.

VD

It was a play he was performing?

JG

Well no, it was a long poem called Unter dem Milchwald (Under Milk Wood). It was these six famous actors and him in the center. It was packed. I had reserved a seat in the front row, and there’s Thomas, pouring sweat and spitting as he spoke. Being fourteen, I couldn’t believe this was poetry. He returned for a performance the next year and I went back, and then I went a third time, and then he died. A couple of years later I’m in Columbia College and on Broadway there’s a production of Unter dem Milchwald. Seeing Dylan Thomas perform did profoundly and nonverbally change my life.

VD

I saw the movie.

JG

Yeah, then the movie came out, and I bought that record and played it endlessly.

VD

I didn’t know you had seen Dylan Thomas!

JG

There was a big gap between when I first saw him and when I was forced to become a performer, through circumstance—I was a poet and I had to perform. I started with shaky legs and it took a few years to figure out what I was doing. Dylan Thomas had gone off my radar. My understanding of deep breath—I came upon it by myself and worked on it by myself. I didn’t realize that what he did was the same thing. Anyway, I figured out a method of using my breath and flow of air in the higher, middle, and lower parts of the chest and stomach. I suppose if you’re an opera singer or any kind of singer, you are taught how to use your inner breath. I wasn’t. So I had to discover it myself.

VD

Is it strictly stagecraft?

JG

I perform using my breath in a certain way and then I do these other things. But performing is not exactly key to being a poet.

VD

It’s a much more traditional way to be a poet—

JG

Yeah, I had to develop skills. In the 1940s, there was no such thing as a poetry reading.

VD

Poetry was just something typed on paper.

JG

In the ’50s, when he began, Allen Ginsberg was not the greatest performer. But he became a great performer. So Dylan Thomas was my only point of reference until Allen Ginsberg and the Beats. But we come from a long tradition of American performers who would tour the country and wow the people. For me, it’s just amazing that there was no tape recorder and all of that is lost. Mark Twain being a fabulous performer is sort of a myth.

VD

I mean Homer was probably pretty good, too. (laughter)

JG

Slam poetry basically introduced the idea of performing mixed with rock energy.

VD

But there still seems to be a clear split between the high-academic poetry world and the popular or slam poetry or rock and roll poetry world. I asked you once, how was it that you got through the ’60s without ever learning to play guitar?

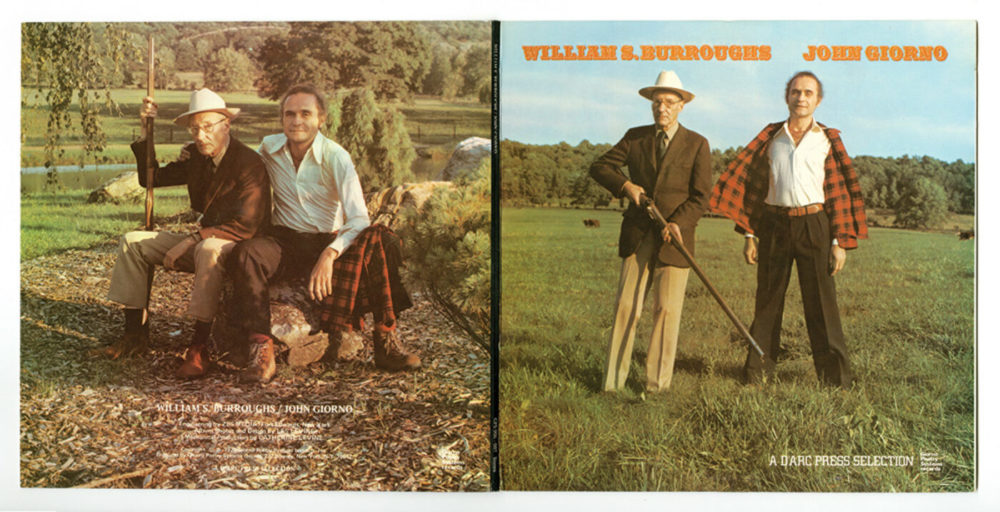

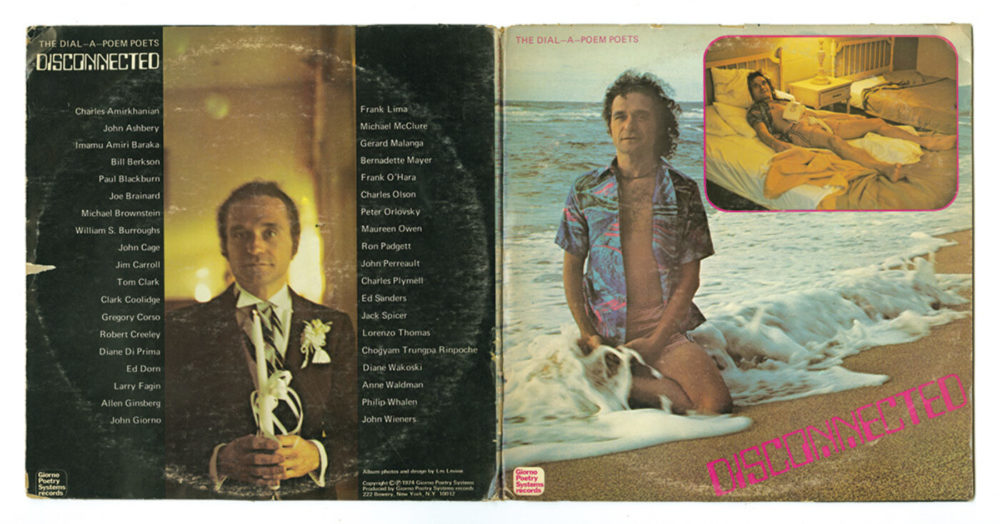

Back cover and cover of William S. Burroughs / John Giorno, 1975, Giorno Poetry Systems. Photo and design by Les Levine.

Back cover and cover of Disconnected (The Dial-A-Poem Poets) 1974, Giorno Poetry Systems. Photo and design by Les Levine.

JG

I could have, yeah. But I claimed the piano. I just made a decision that I would perform, but not be a musician. I didn’t have expertise as a singer. I wanted to use my voice the way a poet would think of using it and I developed down that path. Much later, I did a meditation called Tummo, which means “generation of heat.” In paintings you often see a yogi in the snow sweating, generating heat. You move air up and down inside your central channel. In the meditation you use that energy for training the mind. I adapted it to my performances.

The rule I came upon fifty years ago with the Poetry Systems LPs was that only a poet can read his or her own work. Because the magic in the person’s breath is inherent in the sound of the words somehow. Actors can‘t do it, no matter how good they are. It’s just an actor reading a poem. From Richard Burton down to the worst, it never works.

VD

That’s Richard Burton reading Dylan Thomas in Under Milk Wood, right?

JG

Yeah. It’s a completely different thing.

So being a poet is one trail to becoming a performer. It’s nice when your books get published, but at a venue you have an audience. And it goes on from there to the recordings to YouTube.

VD

Compared to the past, we have such an incredible amount of recording technology now.

JG

Another part of my story of becoming a performer goes back to when I was nine years old. World War II had just ended. I had a tumor between my optic nerve and my brain. So in 1945, they had figured out a way to cut the bone, go in and remove the tumor, and put the bone back. That saved my eye. Otherwise they would have had to cut my eye out to get to the tumor. I would have had to have a glass eye. It was an experimental operation they had developed during the war. The surgery was a big risk, but it was a great success and a breakthrough for my doctor, Algernon Reese. So at the American Medical Association convention the next year, he presented me. There was a press conference, and they told me that there would be a lot of people snapping pictures. They took me into this room, and, you know, it was like Rita Hayworth’s Hollywood, those big black cameras with flashbulbs, a hundred of them, and they suddenly were all popping. And I said to myself, “This is like being a movie star.” It lasted only one minute, I think, but that was a great moment in my life.

VD

Your first day of superstardom. I thought it came somewhat later. (laughter)

JG

I know. The reason I brought that up is, a year later, a lawyer friend was visiting my family. I was mostly in my bedroom, drawing, making collages, pasting things into scrapbooks. I had been bed-bound or room-bound in the months following the operation. So this lawyer says to my father, “I see John’s in his bedroom all the time. He has to get out of the house.” But I couldn’t play sports because of the operation.

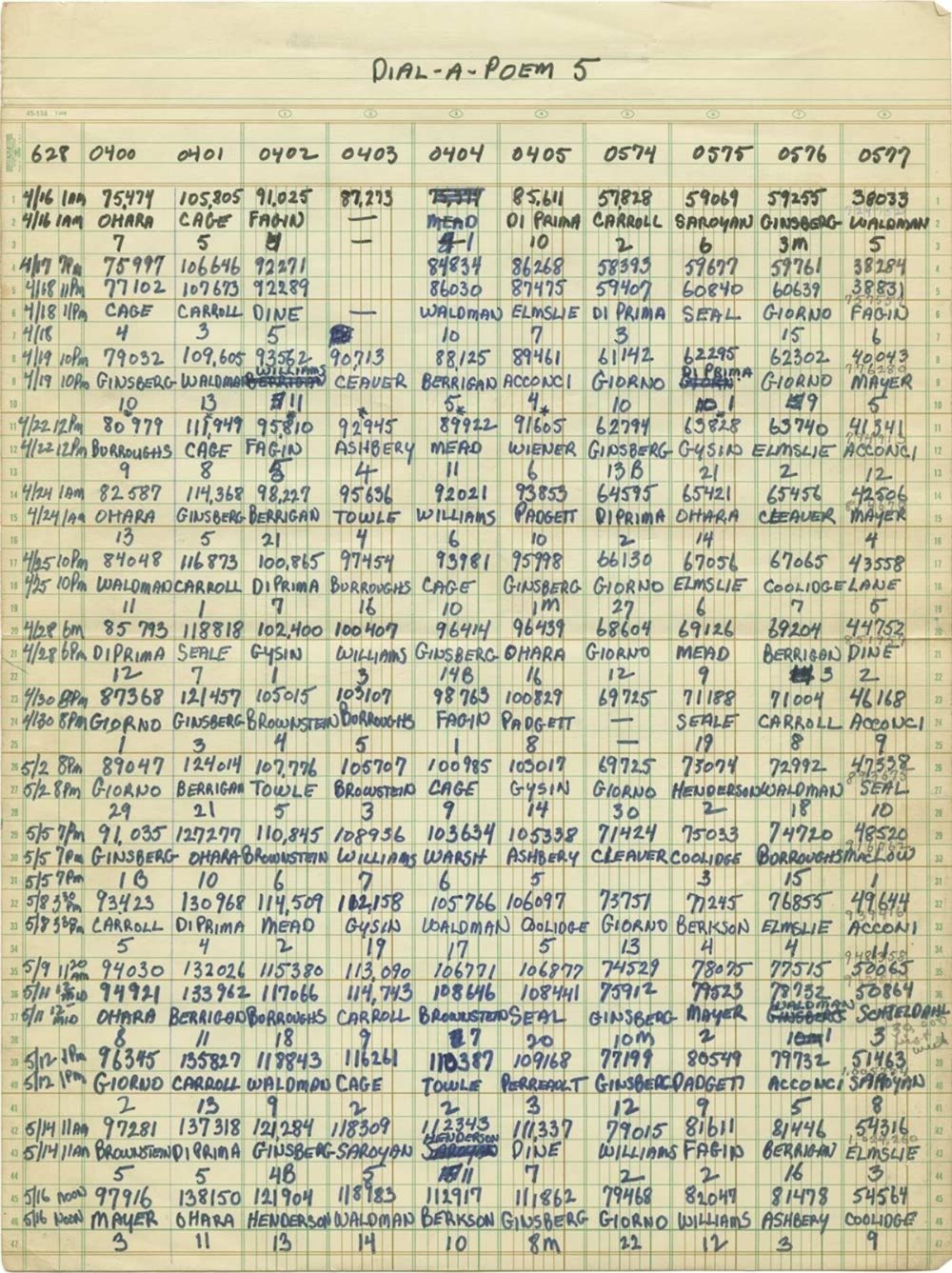

Reading schedule for Dial-A-Poem 5, the Architectural League of New York, 1969.

VD

”He’s going to be a priest if you don’t get him outside!”

JG

The lawyer said, “I see he’s interested in art.” And I overheard him telling my father to send me to art school. So two weeks later, my father suggests that I go to Pratt Institute, and I start going to a Saturday program for young people. I was only ten and a half, and everybody else was twelve or fourteen or seventeen. I went there for three years and studied drawing and painting until I started high school. But all the things that I do now as an artist are somehow rooted in those years at Pratt.

VD

And when did you start to write poetry?

JG

Around the same time. I wrote my first poem as a homework assignment. The year 1950 was like the Stone Age, before television, before everything. I felt that poetry was sacred and it wasn’t something that you could do yourself. But one day my teacher said to the class, “Go home and write a poem,” I was shocked. I could go home and write a poem?

VD

You’re not John Milton.

JG

Yeah. Not to digress, but it wasn’t like now where everybody’s taught to be creative from one and a half years old. So I handed in my poem and, after a few days, the teacher said, “I’ve read all of your poems, and these are the three I like best.” She read the first one, the second one, and mine was the third. I said to myself, “I liked doing this. I’m going to write some more.” So that was my change in high school from sort of being an artist to being a poet. At my school, there was this group of older students who were very intellectual and ran a literary magazine, the Madisonian. I immediately gravitated toward them. So that’s how I got started.

VD

What did you do after you graduated from Columbia University?

JG

I went to a place called the Iowa City Writers’ Workshop, run by Paul Engle. That was in ‘58. Now there are so many great poetry institutions and programs, but back then, Iowa was really the only one in the country. And it was quite prestigious. So I went out there and hated it. It was modernist poetry, and I was still figuring out what I was going to do as a poet. I only lasted there six months. Maybe nine.

VD

And then you came back to New York?

JG

Came back to New York.

VD

When and how did you meet Robert Rauschenberg?

JG

I came to this loft here on the third floor, when I returned from Morocco in ‘66. I knew Bob from the art scene in the early ’60s. Lucinda Childs and Jill Johnston were good friends of mine in those years. So when I got back from Morocco, I saw them right away. And they said, “Bob is working on this thing and he needs help. They’re asking for volunteers and you should go.” Then I’d see them a week later and they would say, “John, Robert Rauschenberg needs help and you should go.” The third time, I said, “Oh, well I will go. If you keep saying it.” So I went and volunteered and got involved with EAT, Experiments in Art and Technology. And we became friends. It was really formative because the year before I had started making sound poetry, a concept introduced to me by Brion Gysin.

VD

You were in Morocco with Brion Gysin.

JG

Yeah. Brion was one of the founders of sound poetry, poesie sonore, with Bernard Heidsieck. The idea was to create sound compositions using whatever technology was available. In 1960, Brion had been to the BBC studios, which had an electronics lab. He suggested that I do a collaboration with him. I was this young poet, not anywhere an equal, and I was shocked, but we did it. I had just finished a poem called “Subway.” So we went down into the subway and recorded subway sounds and made them into my first sound poem—”Subway Sound.” Then that got presented at the Museum of Modern Art in Paris in the Biennale of ‘65, and I said, “I want to do more of that.” So I started working with whatever technology was around. The year 1965 was a very exciting time in New York City. Steve Reich, Max Neuhaus, and Phil Glass were making these sound loops with their instruments.

VD

And reel recorders?

JG

Yeah. I thought, I can do that using words rather than musical sounds. So suddenly I’m in EAT with Bob and I get introduced to Bob Moog who invented the Moog synthesizer. Soon I started recording using the audio technology with sound engineer Bob Bielecki. I worked for fifteen years making sound compositions in every possible conception I could think of, and then abandoned the idea. Sound poetry never became a real art form or one that mattered in America. So I stopped. I had done everything I wanted.

VD

Did they get radio play? I mean, Citizen Kafka on WBAI would be on from midnight to five in the morning or so, just playing the most amazing, unusual, obscure things.

JG

Well, no. When I started releasing the Giorno Poetry Systems LPs, it was these that were played on WBAI. Because they included everything, from William Burroughs to Allen Ginsberg to Sonic Youth to all the poets who were doing performances. The LP records were part of a whole method of presenting poetry to a public in a way that was successful.

VD

When did you find yourself first getting involved in technology? Would that be with film? And when did you meet Andy Warhol?

JG

In ‘62. We became friends in ‘63. It was a teeny scene—the pop artists and twenty abstract painters and that was the art scene. It was a time in New York City when there were hundreds of small movie houses that were left over from the 1930s, small theaters on the Lower East Side. They only played on the weekends—Friday, Saturday, and Sunday—and were vacant the rest of the week. Jonas Mekas figured this out and would rent them for almost nothing. And that’s where he created the underground cinema that I went to before I met Andy and later went to with Andy. We went as many nights a week as we could.

VD

And what would you see there?

JG

Jonas would show Flaming Creatures, and Scorpio Rising by Kenneth Anger. Flaming Creatures would always be shown before something new. I must have seen it twenty times.

VD

And would he show Robert Breer? What about Hans Richter movies and early Constructivist cinema?

JG

Yeah, all of them. It was like going to school and learning. That’s what Andy did in that year or two that we all went. He learned how to be a filmmaker by just sitting there. What follows is that Andy decides to make a movie and buys a camera. It’s like April of ‘63. So he shoots the first thing with Robin and me on a mushroom. The secret is that Andy had used a camera all his life; that was just the first time he had used a movie camera.

VD

And is that what led you into technology, too?

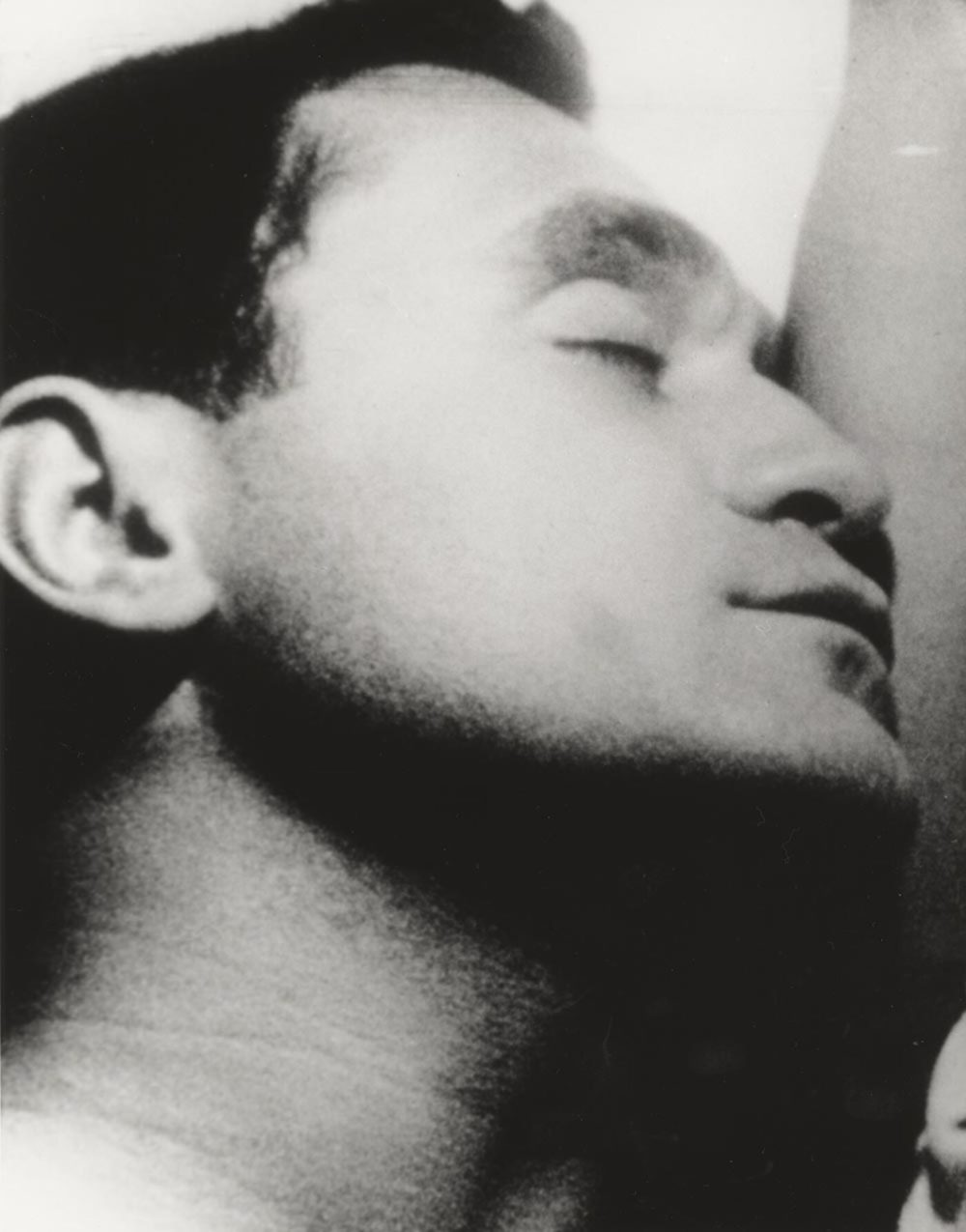

Still of Giorno in Andy Warhol’s Sleep, 1963, 16 mm film, black and white, silent, 5 hours and 21 minutes.

© 2015 The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, a museum of the Carnegie Institute. All rights reserved.

JG

Well no, Andy was six or seven years older than me and he was a little bit lame. So he gets this Bolex and comes to my loft and shoots Sleep. You had to rewind the camera every twenty seconds to do a three-minute roll, so we filmed it over ten days or so. Then he started sending the rolls out to be developed. When he got one back, we looked at this three-minute footage and every twenty seconds the camera was jerking on the stand. So the footage was useless. Finally someone told Andy that Bolex has a gadget that you plug into the wall and it rewinds the film, so you don’t have to rewind it. We had to start filming again. It was one continuous shot for three minutes, but when you put them together, it’s a different cut. Andy tried endlessly to splice them together.

VD

So the interrupted making of Sleep was not a lark. He wanted to make a very long movie of you sleeping, as seamless as possible.

JG

Well, yeah, he essentially would have liked to have made Empire in the bed, but the technology made it impossible.

VD

It seems like there must have been some transition with these artists you were friends with. I don’t know if it was important or not, but they were at the cusp and then they became successful. Suddenly they had a lot of money, right? Or did they?

JG

Well, only the artists did. The poets never did.

VD

At a certain point, Andy’s running with a pretty glamorous crowd, right?

JG

That was after my time. In my years, in ‘63, ‘64, and ‘65, he still did sketches for the New York Times and the New Yorker. He’d say, “I got paid seventy-five dollars or a hundred and twenty-five.” Which, in the early ’60s was like a thousand. But he really depended on this work.

VD

So there was a bohemian experience even for Andy. I can’t really picture him being down and out.

JG

Nobody was down and out. Nobody was poor. When I appeared in ‘61 or ‘62, all these artists had already had their first shows, so nobody was broke. Me personally, I was living with a small allowance from my parents that paid for everything. It was very inexpensive to eat. Nobody was poor. It was an innocent age then from ‘61 or ‘62, whatever you consider it, to the late ’60s when some artists became super rich.

VD

And here you were, a poet in the thick of the visual art world in a certain way.

JG

But in the middle of this same world were Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery, who came through Larry Rivers.

VD

And musicians, too?

JG

I mean Steve Reich and Philip Glass—they’re all my age and eighty years old now. We were all there because it was one scene. John Cage and Merce Cunningham were part of it too.

VD

Tell me about how the Ugo Rondinone: I ♥︎ John Giorno exhibition came to happen in Paris in 2015.

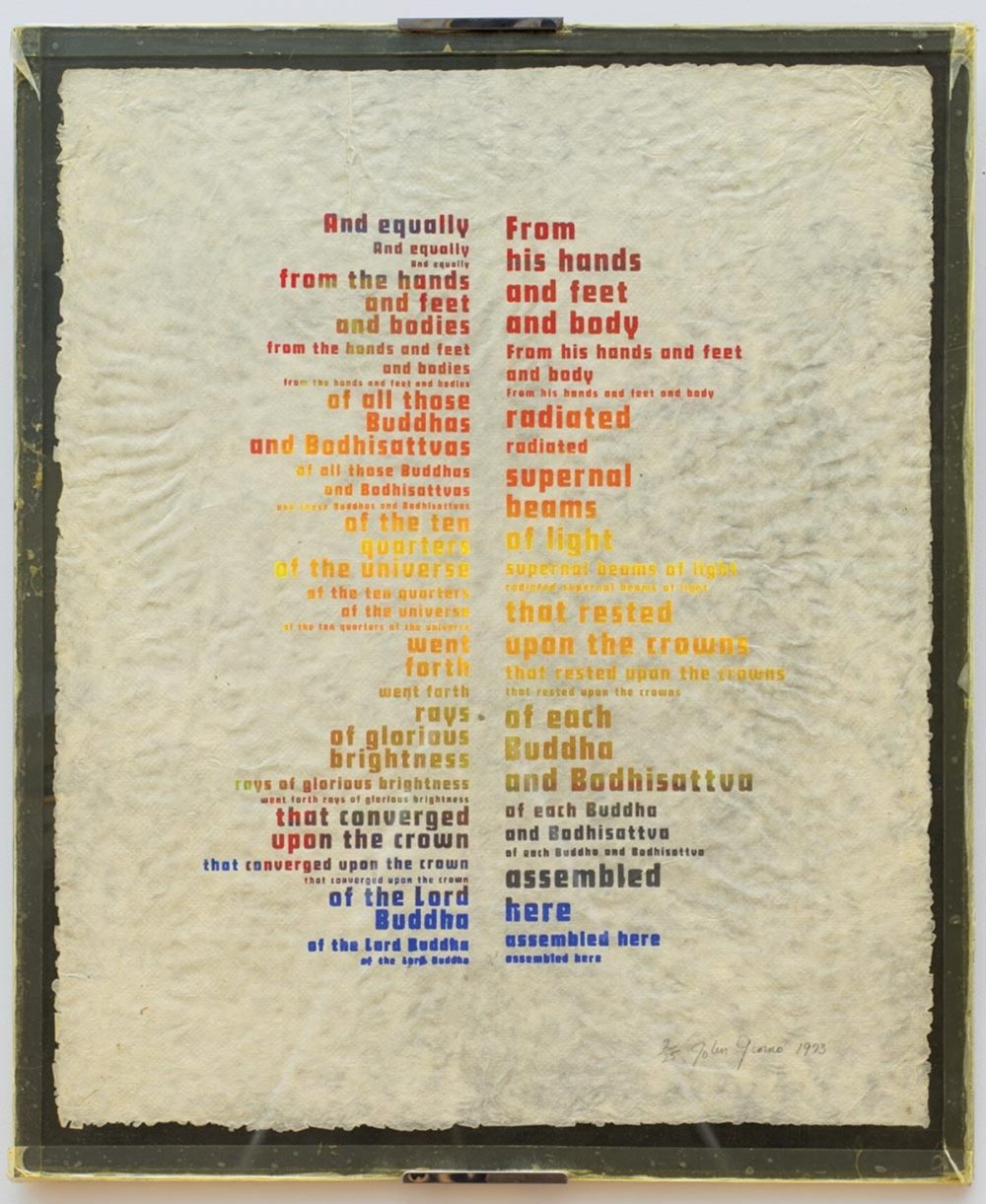

Buddhas and Bodhisattvas Rainbow, 1973, silkscreen on paper, 29 × 24 inches.

JG

Ugo knew that I had this archive out in my family’s house in Roslyn Heights, Long Island. For fifty years, I had saved everything of my own work and what was given to me. There were thousands of cartons, a vast collection. Ugo had been out there and always wondered, What can you do with it? How do you present an archive without making it into a trap of dead things in glass cases? So that lingered in his mind. At the same time, Jean de Loisy, a good friend of mine in Paris, knew about this archive and was wondering how it could be shown at the Centre Pompidou or the Palais de Tokyo. And then, suddenly, Ugo got together with Jean de Loisy, and they started talking about doing an exhibition of the archive. We hired two archivists, and I brought these boxes to New York City, twenty at a time, from Long Island. And they scanned 15,000 pieces—photographs, book covers, event fliers, posters, LP covers, letters from the 1950s to now. Each thing was taken out and put into an individual acetate folder. That took four years. That’s the basis of the archive part of the show. The other parts of the show include the Giorno Poetry Systems and the LPs—you saw that installation with the album covers on those bean bags and iPads to be accessed in the gallery by people. Also my paintings, and works by others about me.

VD

And the most monumental work in the show is the film that Ugo made with you that’s based on your poem “THANX 4 NOTHING,” which is autobiographical, right?

JG

Oh yeah, I wrote it on my seventieth birthday. Ugo always wanted to make a film. And he hadn’t figured it out, and eventually he decided that he would film me performing the poem. So we did this elaborate shoot in Paris for several days, doing it over and over. It had over a hundred different takes.

VD

Of reading the poem in its entirety?

JG

Yeah, in its entirety. Ugo got the two best cameramen in Paris. They each shot from different angles, the back and the side, or the front and the side, far away, medium, close, detail. It was 111 takes and the editing process went on for two or three years.

VD

It was shot on video?

JG

Yeah. It turned out to be one of my best works and it happened thanks to Ugo. The installation was an absolute masterpiece, regardless of my poem and my performance. It was our work coming together.

VD

Congratulations on being a newlywed.

JG

Ugo and I’ve been together nineteen years, and six weeks ago we were married in New York City down at City Hall, and you were our best man and Laura our best woman.

VD

We did our best.

I’m curious, when you reach the point where you’re ready to perform a poem onstage, what has happened between finishing writing and actually performing it? Is there a lot of working out phrases or body gestures?

JG

No body gestures, but preparing the performance takes a lot of time.

VD

Have you memorized the poem by the time you finish writing it?

JG

More or less. I sort of rehearse it as I’m writing it, to see what the sound is, particularly how the phrases relate to each other when spoken. I do that in front of the computer or just sitting in a chair. And then three quarters of the way through composing the poem, I start taking it more seriously, where I actually read or concentrate as if I’m performing. When the poem is completely finished, then I go into a real rehearsal mode. Once the poem’s done, it doesn’t get changed, or occasionally one word might get changed.

I hate rehearsing, but I just force myself to do it every day. And then I get to feel comfortable with it. The first performance usually isn’t in a very important venue because I’m still a little insecure doing it for the first time in front of a large audience. And then I just keep doing it, and a year later, it gets really good.

VD

It’s always great to see a poet reciting without a script.

JG

The poem I wrote before “THANX 4 NOTHING” was “GOD IS MAN MADE.” Then the Charlie Hebdo shooting happened in 2014, and I said to myself, “How could I have written this poem?” Your mind gets poisoned by the catastrophic event and filled with negative thoughts. But I had written the poem before the shooting, so I just finished it. I began performing it very insecurely in a few places, and it became a perfectly accomplished performance. I didn’t perform at the opening of the exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo, but it was arranged that I would go back to Paris six weeks later to perform. The attack at the Bataclan on November 17th happened the night before I departed for Paris. How could I not go? So I arrived on Sunday, when the city was in lockdown. And then I performed on Wednesday, the first day people came out of their houses. There were thousands of people at the Palais de Tokyo, and I did my forty-minute set, but relatively early in it I did “GOD IS MAN MADE,” and the audience was crying and weeping, screaming and cheering. Miraculously, the poem seemed to reflect their mind. It was one of the great moments in my life as poet and artist.

GOD IS MAN MADE

Yes, there is a god

and it is man-made,

there is a god, and it is made by man,

all the gods are made

by you and me,

we create the gods and they look like us.

Yes, there was a moment

recognizing intuitively

the empty true nature of mind,

beyond concepts and inconceivable,

and then we began thinking about it

thinking about it

thinking about it,

made it into ideas,

made it concepts,

made it into religions

invented all the self-serving religions,

and then we said some words,

and said it is the word of god,

words from god,

and everybody believed it

wanted to believe it,

we created god and he looks like us.

Yes, there is no hell,

there are no hell worlds of devils and demons,

other than the hell inside my mind

the hell inside my mind,

the hell inside your mind,

the hell you and I create around us

the hell we create around us

the hell we create around us,

and take with us into death.

Yes, there is no heaven

there are no heaven worlds

other than the joy of you,

heaven is living in your eyes

living in your eyes

living in your eyes,

seeing everybody in the world as gods and goddesses,

every wretched, grasping, ugly person

is a deity

swimming in light.

Yes, gods helping and making happy

helping and making happy,

demons hurting and harming

is your own mind

seeing itself.

Yes, at the moment of death

at the instant of awareness,

the gods are gone,

if you go looking for heaven

you are in trouble,

the gods vanish

within the unborn empty nature of mind,

you are liberated through

your own self-luminous awareness,

your own self-luminous awareness

will always be with you.

Yes, I will always be

with you

I will always

be with you

I will always be with you

I will always be with you

I will always be with you.

Yes, everything is delusion, including the most sacred,

everything is delusion, including the most profound wisdom,

everything is delusion, including the highest most precious teachings

which lead to the realization that everything is delusion,

the play of emptiness

awareness

and bliss,

finding it

through yourself

finding it through yourself

finding it through yourself

finding it through yourself

finding it through yourself,

self-luminous

awareness

ceaselessly coming.

2013–14

Verne Dawson is a painter who lives in New York City and Saluda, North Carolina.