- Source: ARTFORUM

- Author: LAURA HOPTMAN

- Date: February 2020

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

LAURA HOPTMAN

on John Giorno

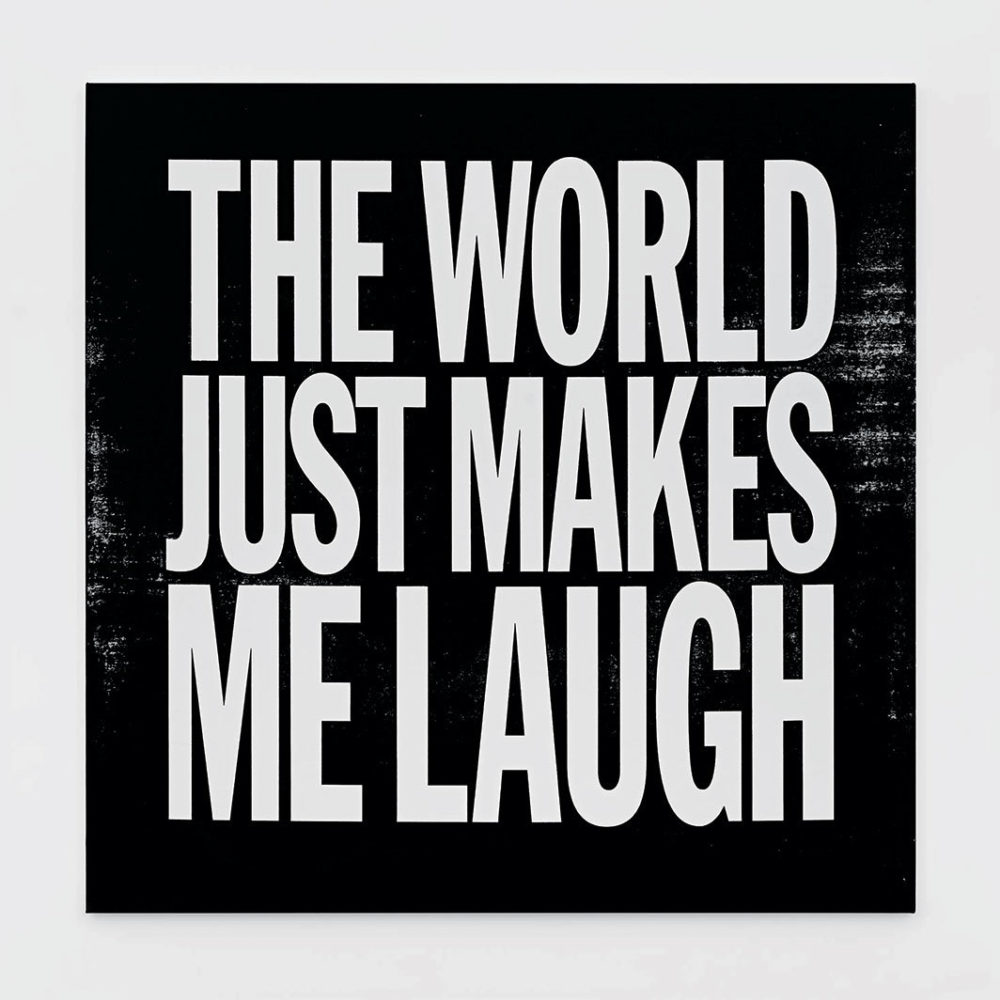

John Giorno, The World Just Makes Me Laugh, 2017, silk screen on canvas, 48 × 48".

JOHN GIORNO, who left New York and this world on October 11, 2019, at the age of eighty-two, was one for the pantheon. He described himself as a poet, though in his brilliant life he was also a visual artist; a performer; a record producer and distributor; a civil-rights, gay-rights, and aids activist; a central, vocal member of the Tibetan Buddhist community in America; and a philanthropist who quietly supported poets and artists in need. A beautiful, social being with a smile that was like sunshine, he also inspired generations of our country’s most radical artists, writers, musicians, filmmakers, critics, and idols of the beau monde. John knew them all, and was among the most radical of them all, using his remarkable gifts of language, charm, and creative fortitude in the service of what can be described as positive subversion: the celebratory smashing of political, social, sexual, cultural, and metaphysical conventions.

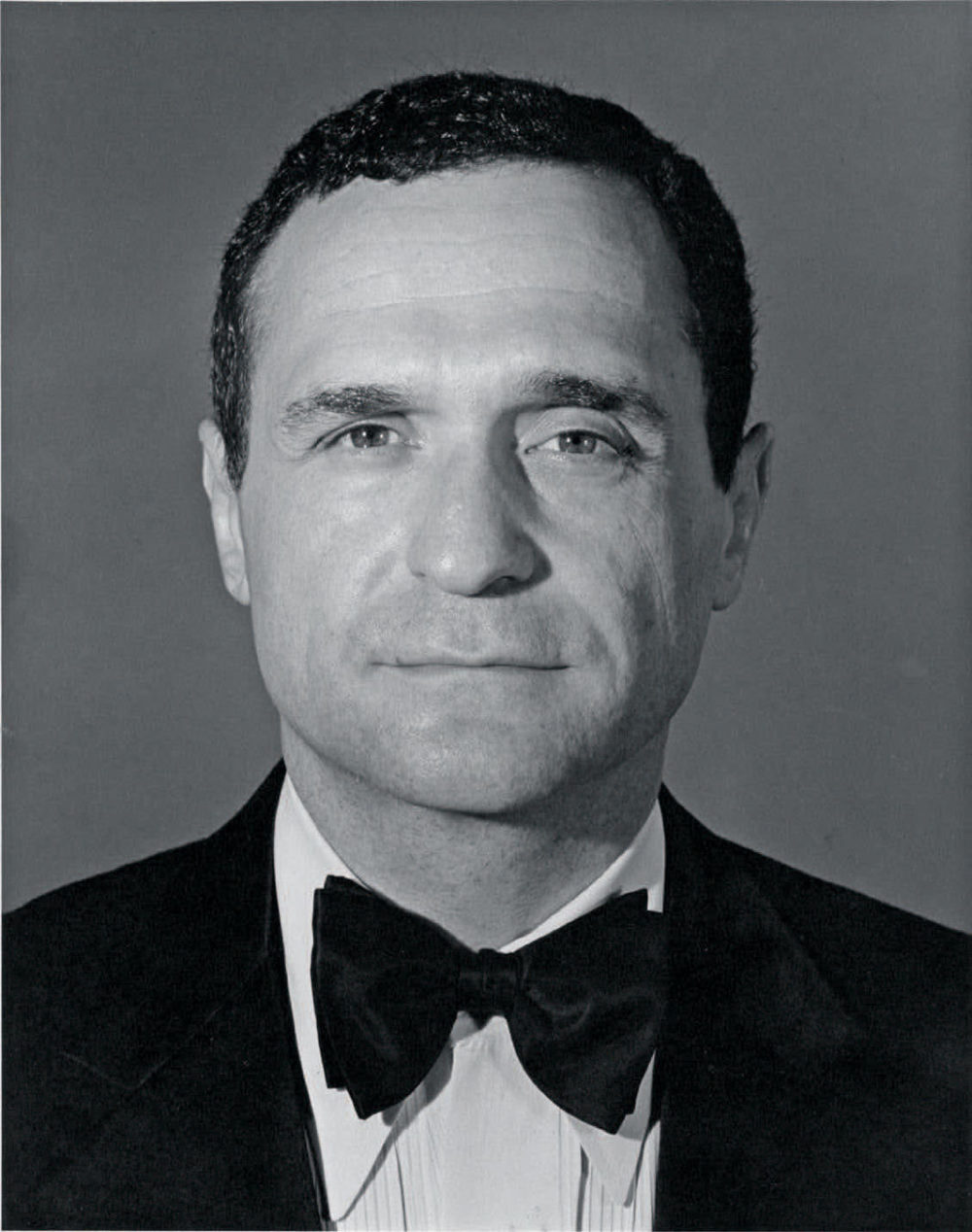

John Giorno, New York, 1980. From the album art for Sugar, Alcohol, & Meat: The Dial-A-Poem Poets

(Giorno Poetry Systems, 1980). Photo: Robert Mapplethorpe.

He was precocious, beginning art classes at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn at age ten and writing his first poems at fourteen. He was exposed to contemporary poetry as an undergraduate at Columbia University, where he saw Dylan Thomas perform and where he read the poems of Federico García Lorca and Allen Ginsberg. In 1961, John fell in with an art crowd that included Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, and, momentously, Andy Warhol. Captivated by John’s charisma, Warhol cast him in a number of short films, most notoriously Sleep (1963), a five-hour-and-twenty-one-minute black-and-white record of John slumbering peacefully. Sleep made John famous, presenting him as the quintessential muse: exquisite, unconscious, and anonymous. In fact, this moment of somnambulant superstardom signaled his awakening, marking the beginning of his poetic and artistic life. Inspired by Warhol’s found-image silk screens, John began to compose poems stitched together from headlines clipped from the New York Post and the Daily News. These works were pledges of allegiance to Pop and a sharp turn away from the New York School poetics that dominated literary discourse at the time.

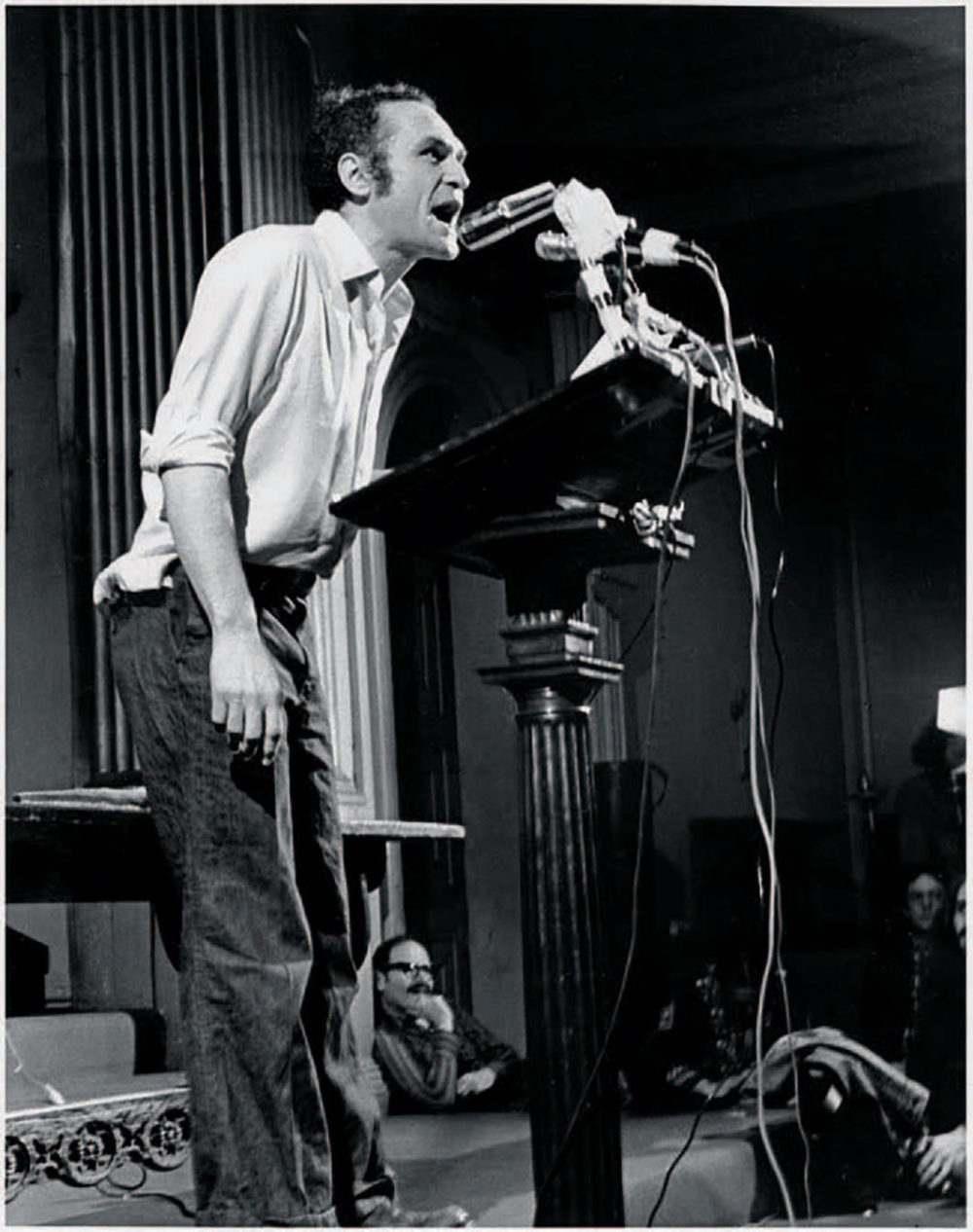

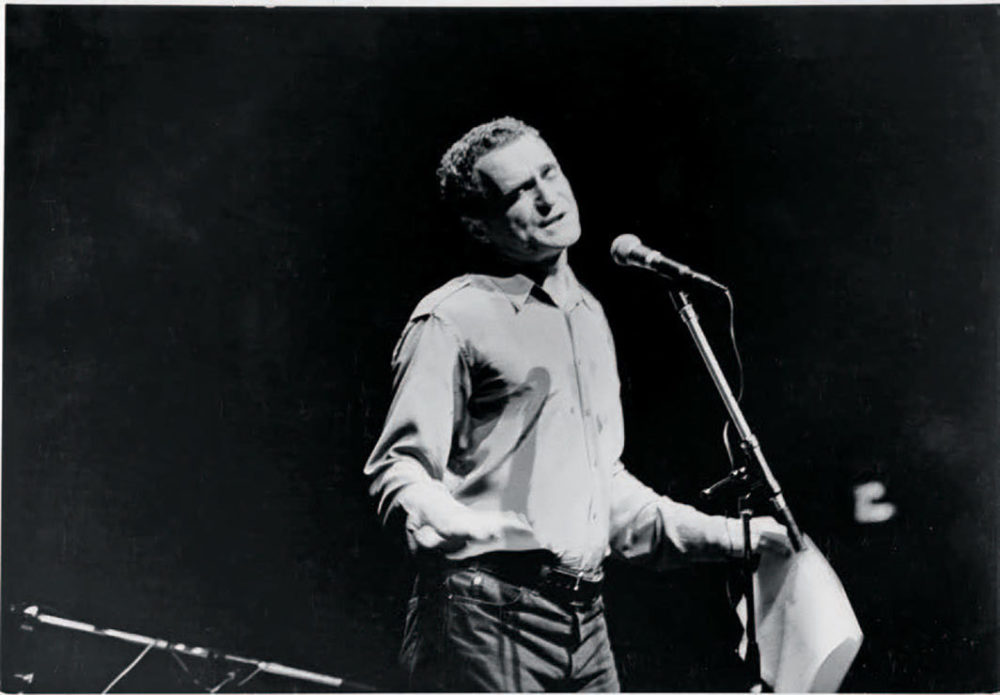

John Giorno giving a reading at St. Mark’s Church, New York, April 28, 1974. Photo: Gianfranco Mantegna.

In 1966, John moved to 222 Bowery, an imposing nineteenth-century building, formerly a YMCA, that had provided a home or studio for artists such as Fernand Léger, Mark Rothko, Michael Goldberg, and Lynda Benglis. It was shortly thereafter that William S. Burroughs and the polymath poet, artist, and mystic Brion Gysin rendezvoused in a loft downtown and began their collaboration on The Third Mind (1978), a project of cut-up and assembled texts and images that both considered a “book of methods” for merging visual art and literature. John was with Burroughs and Gysin during this period—he believed in their work and served as a tireless helpmeet for both—and the experience changed his poems. For a time, he organized them into split or double lines of text running parallel to each other down the page, allowing for chance juxtapositions of stanzas. In 1975, John found Burroughs a New York redoubt: a windowless space in the basement of 222 Bowery that Burroughs called “the Bunker.” The space suited the author’s dark and paranoid point of view so well that he lived in it for seven years. When Burroughs moved out in 1982, John transformed the Bunker into a space for Buddhist teachings and meditation, retaining its nickname in Burroughs’s honor.

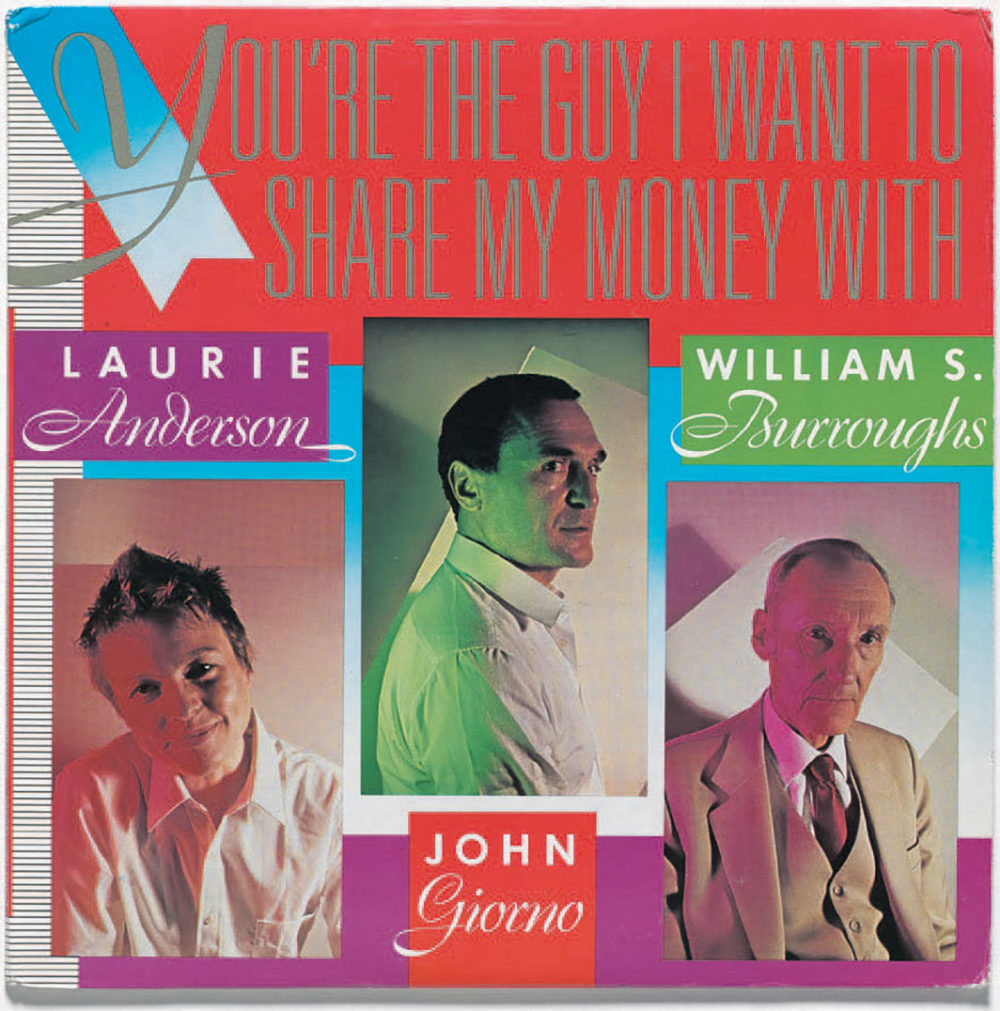

William S. Burroughs, John Giorno, Laurie Anderson, New York, 1981. From the album art for Laurie Anderson,

John Giorno, and William S. Burroughs’s You’re the Guy I Want to Share My Money With

(Giorno Poetry Systems, 1981). Photo: Jimmy DeSana.

Since the beginning of his career, John was interested in democratizing the distribution of poetry so that it could reach a wider audience. In the mid-’60s, he began chopping up longer poems into exclamatory stanzas, laying them out like tabloid headlines and printing them on all manner of cheap, reproducible objects, ranging from neon-colored flyers to T-shirts, to his now well-known silkscreens on canvas. Fascinated by magnetic-tape recording, he became involved with the Paris-based poesié sonore (sound poetry) movement, making lifelong friends of its founders, Henri Chopin, François Dufrêne, Bernard Heidsieck, and Françoise Janicot. The activities of the sound poets, which featured live and recorded experiments with magnetic tape, set the stage for John’s best-known work, which marked his first highly visible foray into the art world: the interactive installation Dial-A-Poem.

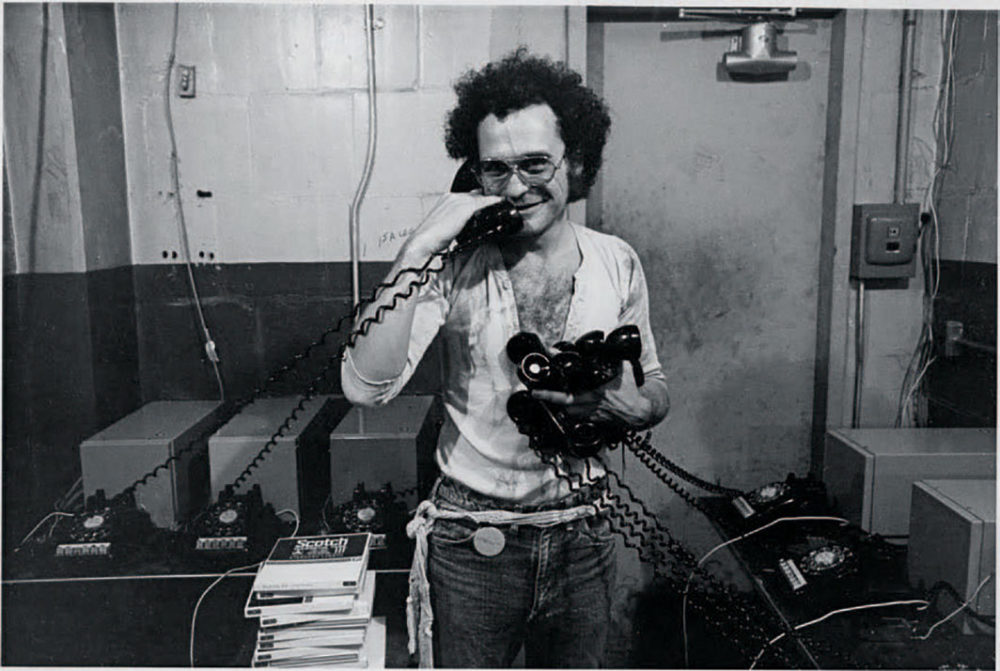

John Giorno with his 1968–70 Dial-A-Poem, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1970. Photo: Gianfranco Mantegna.

In essence, Dial-A-Poem was a series of toll-free telephone numbers that a person could call to hear recordings of the greatest poets of that era—like Ginsberg and John Ashbery, Diane di Prima and Anne Waldman—reading their own work. John exhibited it in 1969 as an interactive installation, first at the Architectural League of New York and then in 1970 as part of “Information,” Kynaston McShine’s landmark exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, which presented artist-created systems of information organization as Conceptual art. It was such a success that it convinced John that audio recording was the most effective and subversive way to bring poetry out of the subculture and into the wider world. Beginning in the 1970s, he set about releasing LPs of hundreds of poets, artists, and activists reading their own poetry. Starting a record label under the industrial-sounding name Giorno Poetry Systems, John recorded everyone from Ashbery to Frank Zappa, Kathleen Cleaver to John Cage, and Joe Brainard to Debbie Harry, and produced and distributed anthologies like Life Is a Killer (1982), which featured Amiri Baraka, Jim Carroll, Jayne Cortez, and the classic You’re the Guy I Want to Share My Money With (1981), with Burroughs and Laurie Anderson.

He was disciplined, inscrutable, a unique performer—both powerful dharma seer and folksy prophet.

Cover of Laurie Anderson, John Giorno, and William S. Burroughs’s You’re the Guy I Want to Share My Money With

(Giorno Poetry Systems, 1981).

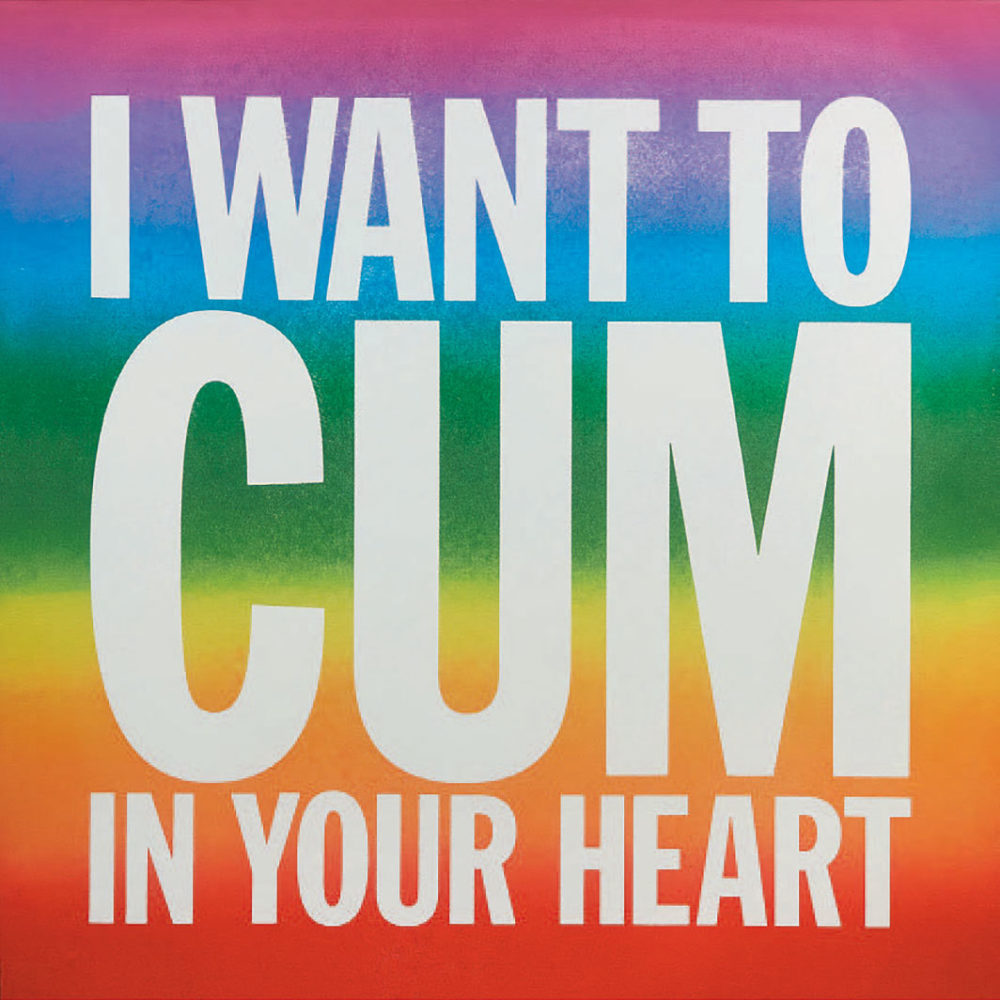

In his literature, art, and lifestyle, John set an example of how to buck what Burroughs famously called “Control”—and of how to not die but thrive doing it. John’s work is joyfully out and defiantly porn-positive: From his 1965 panegyric about a gangbang (“Seven Cuban / army officers / in exile who were at me / all night”) to his more recent paintings declaring I WANT TO CUM IN YOUR HEART, he made sure that his life was an example of absolute freedom from social convention and that his work was a volley of buckshot aimed at the nannies of twentieth-century middle-class American social mores. As he said many times, always with a gentle smile and a joint in his hand, “They can all go fuck themselves.” Society, by the way, periodically clapped back at him. For decades, the snootier precincts of the New York School omitted him from their magazines, anthologies, and cushy residencies. Around 1969, in the midst of his antiwar work, the FBI sent him a surprise package containing a lot of marijuana, for which he was briefly imprisoned. And while he was invited to the opening of the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh in 1994, his relationship with the Pop artist, both professional and romantic, has effectively been written out of the official Warhol biography.

John Giorno, I Want to Cum in Your Heart, 2017, ink-jet print, 26 × 26".

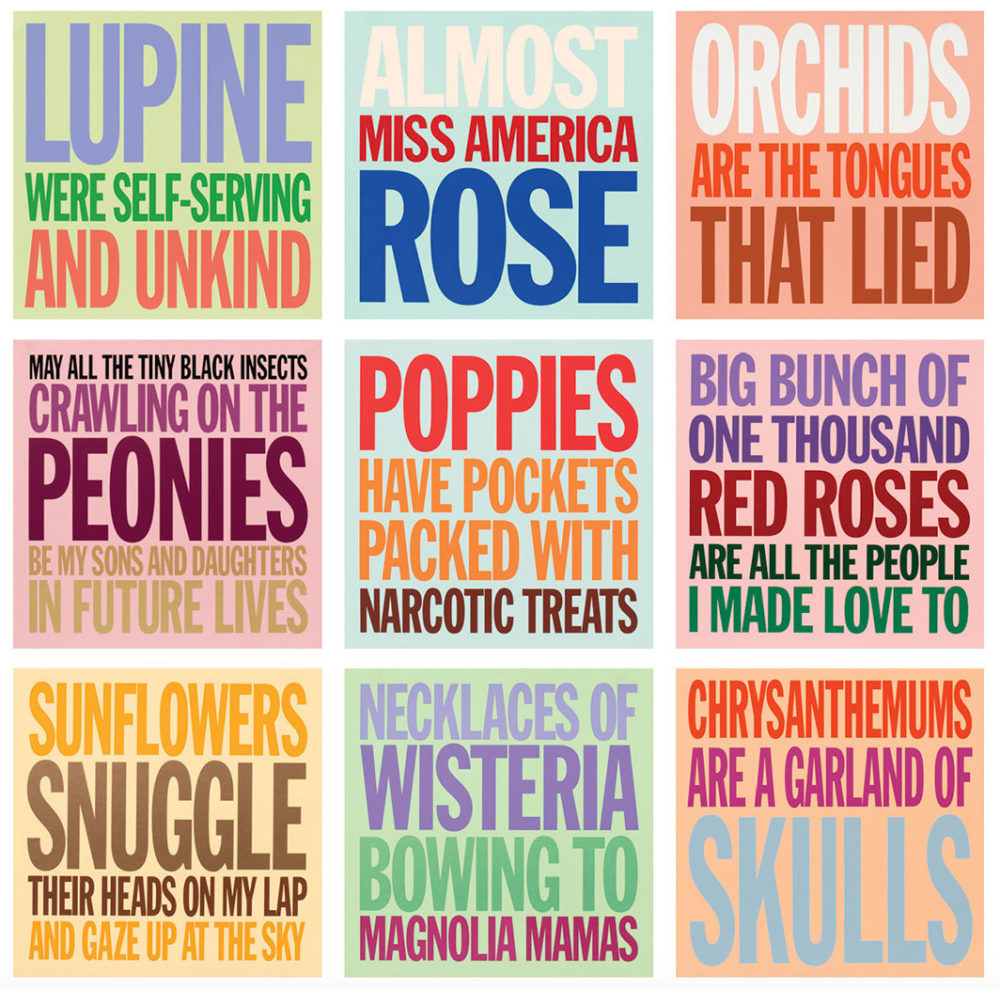

In 1997, John met his future husband, the Swiss artist Ugo Rondinone, who would introduce John’s work to a new generation of artists, writers, and curators (including me). It was Rondinone who encouraged John to return to making visual art, and who reintroduced his work to the art community in an exhibition he curated for the Swiss Institute in New York in 2002. Thereafter, John began to produce visual art with regularity, from ecstatic print portfolios like Welcoming the Flowers, 2007, to his final series of paintings and sculptures, which was on view in a solo exhibition at New York’s Sperone Westwater gallery at the time of his death.

John Giorno, Welcoming the Flowers, 2007, a suite of eighteen silk screen prints on board, each 16 1⁄2 × 16 1⁄2". © Durham Press/John Giorno.

John was a consummate and unforgettable performer, and a legendary reader of his own work who, with protean breath control and physical stamina, could recite his poems from memory no matter the length. (His mnemonic feats were, by his account, made possible thanks to meditation, which he practiced four hours daily for more than forty years.) John read not only with his voice and his distinct Noo Yawk inflection, but also with his entire body, having developed a repertoire of gestures that had a distinctly punk-rock energy. He electrified his audiences, bringing them to their feet even at the sleepiest of gatherings.

In his literature, art, and lifestyle, John set an example of how to buck what Burroughs famously called “Control”—and of how to not die but thrive doing it.

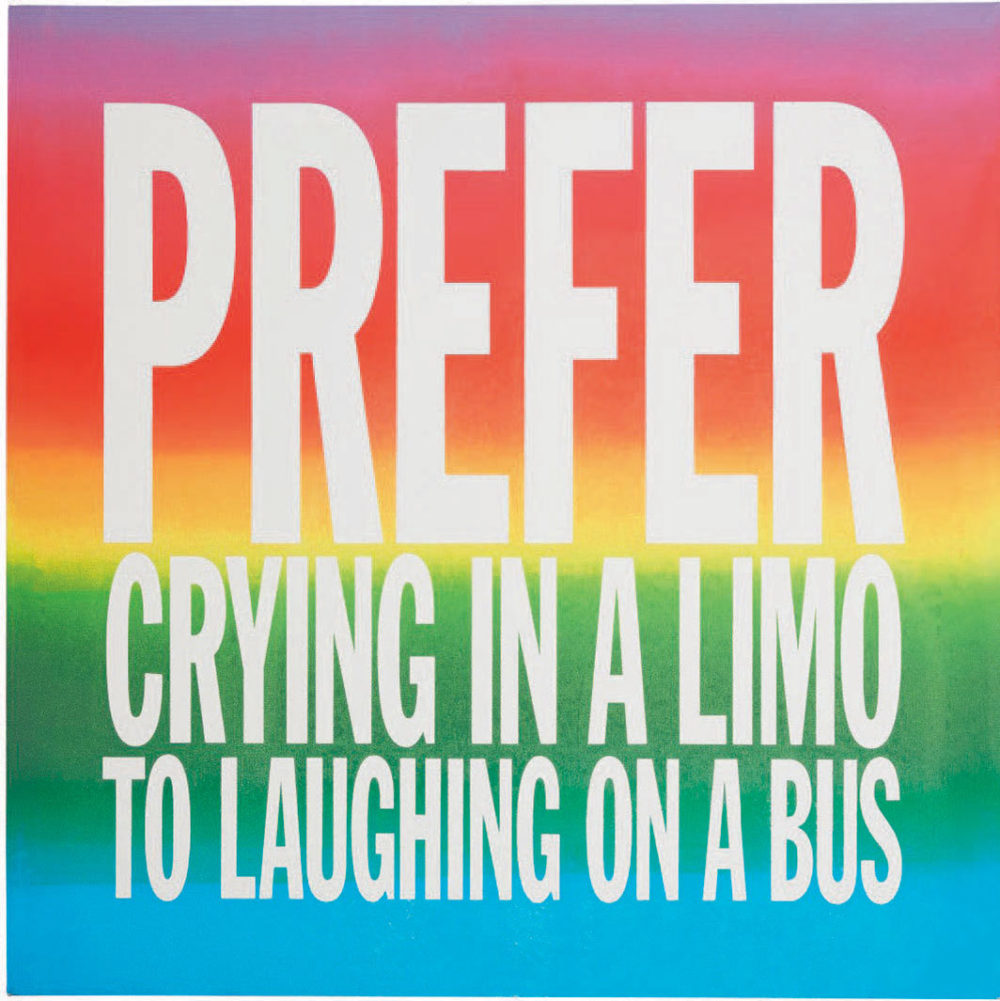

John Giorno, Prefer Crying in a Limo to Laughing on a Bus, 2017, ink-jet print, 26 × 26".

In the past ten years, the art world finally came to understand what literary festivals internationally had known for decades, and John’s relentless touring on the poetry circuit began to include performances at major museums and international biennial events. “Prefer crying in a limo to laughing on a bus,” John wrote, and he was never one to decline an appearance at an art opening, a glamorous party, or a photo shoot. He looked great in a tux, as anyone who watches Rondinone’s twenty-channel video installation featuring John reading his epic poem “Thanx For Nothing: On My 70th Birthday” (2006) can attest. I recommend you see it, as John’s performance makes clear that he both delighted in his belated embrace by the art world and recognized that it was all bullshit. As he wrote to the cultural community to which he gave so much:

thanks for celebrating me,

thanks for the resounding applause,

thanks for taking everything for yourself

and giving nothing back,

you were always only self-serving,

thanks for exploiting my big ego

and making me a star for your own benefit

thanks that you never paid me,

thanks for all the sleaze,

thanks for being mean and rude

and smiling to my face

I am happy that you robbed me,

I am happy that you lied

I am happy that you helped me,

thanks, grazie, merci beaucoup.

John’s life inevitably became a work of art when, in the fall of 2015, his husband created “Ugo Rondinone: I ♥ John Giorno,” an artwork-cum-exhibition by and about John that contained his extensive archives, publications, and recordings; the entire Giorno Poetry Systems catalogue; his paintings, watercolors, prints, and multiples; and—finally—paintings, films, videos, and songs by numerous generations of artists who were inspired by him. A sweeping multimedia portrait of John by the love of his life, “I ♥ John Giorno” was also a public proclamation of how much John had given the New York art world and how much we had happily taken from him. “It doesn’t get better!” reads the inscription from John in my copy of his 2008 poetry collection, Subduing Demons in America: Selected Poems, 1962–2007. It’s a quote from one of his poems, and a classic John line. His deep Buddhist beliefs allowed him to always find joy in lived experience while accepting the inevitable presence of suffering in all aspects of life. To quote another of John’s poems from an epic period in his production: “It’s not / what happens, / it’s how you / handle it.”

John Giorno giving a reading at Centre Pompidou, Paris, June 10, 1983. Photo: Françoise Janicot.

John had just finished writing his memoir when he died, using his carefully tended archive as well as his prodigious memory to recall the details of his life. In its last paragraphs, he emphasizes his readiness for the next big experience in his life—his death. He reiterated his preparedness in a number of poems he produced in his final decade and a half on earth. As he wrote in 2004, “I go to death / willingly, / with the same comfort and bliss / as when I lay my head / on my lover’s chest.” I regret that John came into my life a mere twenty-two years ago, but in that short period I tried to see him perform as much as possible. I was fortunate to hear him read my favorite of his poems, “Everyone Gets Lighter” (2002), enough times to quote bits of it. A Buddhist explanation of the complex notion of emptiness, the poem concludes:

Everyone

gets

lighter

everyone

gets lighter

everyone gets

lighter

everyone gets lighter,

everyone is light.

The sentiment still uplifts me even though I know that a light has gone out in New York, a light that illuminated the very best and worst of the art world and human nature.

Laura Hoptman is a curator of contemporary art and the executive director of the Drawing Center in New York.