- Source: The New York Times

- Author: Randy Kennedy

- Date: October 13, 2019

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

John Giorno, Who Moved Poetry Beyond the Printed Page, Dies at 82

He starred in an Andy Warhol movie, “Sleep,” but was best known for his efforts to bring poetry into the modern age.

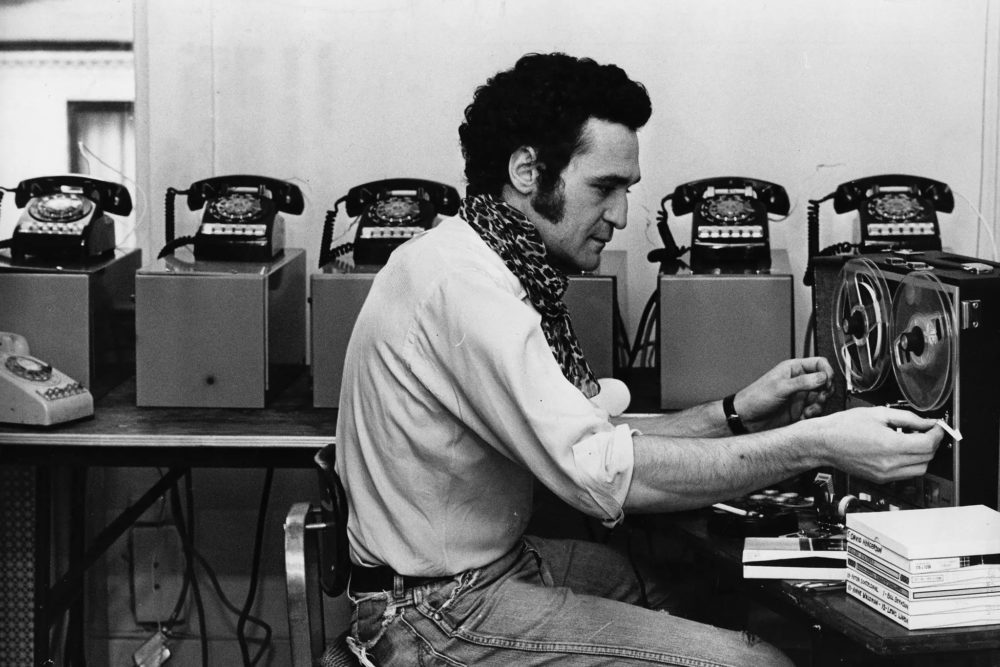

John Giorno, poet and organizer of the Dial-A-Poem project, setting up a reel of recorded poetry at the Architectural League in Manhattan in 1969. Photo Credit: Patrick A. Burns/The New York Times

John Giorno, who turned to the world of art and the mechanisms of mass media to shake poetry loose from the page and embed it more deeply in the fabric of everyday life, died on Friday at his home in Lower Manhattan in a building that he had made into a gathering place for practically everyone from the avant-garde of his time. He was 82.

His death, after a heart attack, was confirmed by the artist Ugo Rondinone, his husband.

Possessed of Greco-Roman good looks and a gregarious, benevolent spirit, Mr. Giorno played an important role early in his life as a muse and lover of other artists, among them Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol. Warhol created his seminal 1963 film “Sleep” by focusing a mostly static Bolex movie camera on Mr. Giorno’s slumbering body for more than five hours, turning him into a filmic, Pop-era version of Mantegna’s Christ.

But Mr. Giorno’s lasting contribution to art came through his restless experiments in the circulation and political potential of poetry, which he felt had been unjustly overshadowed by other genres of expression.

“It occurred to me that poetry was 75 years behind painting and sculpture and dance and music,” he told the curator Hans Ulrich Obrist in 2002, adding that he had been inspired, in part, by the way the work of Pop artists jumped the rails of the traditional art world and reached a broader audience.

“In 1965, the only venues for poetry were the book and the magazine, nothing else,” he said. “Multimedia and performance didn’t exist. I said to myself, ‘If these artists can do it, why can’t I do it for poetry?’”

That year he founded Giorno Poetry Systems, a nonprofit foundation, to promote his work and that of his peers. Four years later, inspired by a phone call with his friend, the writer William S. Burroughs, he started Dial-A-Poem, a rudimentary mass-communication system for cutting-edge poets and political oratory.

Initially using six phone lines connected to reel-to-reel answering machines in a room at the Architecture League on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, it was callable around the clock for anyone with a few minutes and a desire to be read to.

Millions of people dialed in, hearing verse recited by poets like Allen Ginsberg, Anne Waldman, Peter Schjeldahl and Ron Padgett, later joined by dozens of other poets and groups like the Black Panthers.

At a time when the culture at large and the art world were still relatively prudish and also deeply homophobic, Dial-A-Poem — which was featured in the highly influential Information exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1970 — was often unabashedly erotic and heavily gay in content. (The service is still in operation, now at the number 641-793-8122.)

“It seems strange that in 1968, everything was still externally puritanical,” Mr. Giorno told Mr. Obrist. “We all took lots of drugs, and in our personal lives were liberated. But in the media, and outside world, pornographic or erotic images were never used.”

His own work drew heavily from the ideas of the found imagery that fueled the Pop revolution and also from the tradition of the ready-made — plain, found objects presented as art — articulated by Marcel Duchamp and filtered through the writing of Burroughs and Brion Gysin. In his earliest work, Mr. Giorno mined news items and presented them virtually untouched as verse, as in this piece from his first, privately circulated collection, “The American Book of the Dead,” in 1964:

A plainsclothesman

was beaten to his knees

by a mob of teenage girls yesterday

when he and his partner

tried to break up a fight

between two girl gangs

in a school yard

in the Bedford-Stuyvesant

section of Brooklyn.

John Giorno was born on Dec. 4, 1936, the only child of Amadeo and Nancy (Garbarino) Giorno. He grew up in Brooklyn and Roslyn Heights, on Long Island. His father, whose family Mr. Giorno traced to Norman nobility in Puglia and Basilicata, Italy, owned a clothing manufacturing company; his mother was a fashion designer.

Mr. Giorno said he discovered his sexuality in his early teens, when he began to lust after attractive priests at his parish church.

He graduated from James Madison High School in Brooklyn, which Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Bernie Sanders attended around the same time. To the end of his life Mr. Giorno spoke of the importance of the English teachers he had encountered at the school. He attended Columbia University, where he met Ginsberg, and graduated in 1958. During a brief stint as a stockbroker he began to befriend artists and poets like Warhol and Ted Berrigan and the filmmaker Jonas Mekas (who died last January).

Mr. Giorno, in the foreground, and his husband, Ugo Rondinone, in 2015 at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris working on Mr. Rondinone’s show called “I Love John Giorno.” Photo Credit: Alex Cretey-Systermans for The New York Times

He and Warhol were living together off and on when Warhol came up with the idea of filming Mr. Giorno sleeping, naked.

“He said to me on the way home: ‘Would you like to be a movie star?’” Mr. Giorno told The Guardian in 2002. “ ‘Of course,’ I said. ‘I want to be just like Marilyn Monroe.’” Though Warhol and Mr. Giorno split in 1964, the movie — which was among the first footage Warhol ever shot and which became an underground classic — linked them indelibly in postwar art history.

By 1966 Mr. Giorno had moved into a hulking Queen Anne-style building on the Bowery that had been built as the first YMCA and that then had a second life as a warren of studios for artists, including Mark Rothko and Fernand Léger.

He eventually occupied three spaces in the building, one of which became known as the Bunker, christened as such by Burroughs, who began living there part time, in a windowless former locker room, in 1975.

After Burroughs’s death in 1997, Mr. Giorno preserved his bedroom just as he left it, with his hat hanging from a hook across from his single bed, his manual typewriter on a small stand and a working blowgun resting against the wall.

In 1963, the artist Wynn Chamberlain gave a 27th-birthday party for Mr. Giorno in the building — an event that became renowned as a remarkably comprehensive snapshot of the emerging art scene at the time: Attendees included Warhol and Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Frank O’Hara, Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, Frank Stella, Barbara Rose, Roy Lichtenstein, John Ashbery, Merce Cunningham and John Cage.

“They didn’t really know me,” he told Mr. Obrist. “It was billed as a Pop birthday party for a young poet. By the late ’60s, everybody became very famous and nobody went to anybody’s party anymore. It was over.”

For more than three decades Mr. Giorno, a longtime practicing Buddhist, hosted annual gatherings known as fire pujas for hundreds of Tibetan Buddhist adherents.

Over several decades, Giorno Poetry Systems produced dozens of albums, videos and events of the work of Mr. Giorno and other writers, musicians and artists, and in 1984 the foundation started the AIDS Treatment Project, which disbursed hundreds of thousands of dollars to help those suffering in the epidemic. He also long pursued his work through painting and sculpture and has an exhibition of new pieces still on view at the Sperone Westwater Gallery in Lower Manhattan, through Oct. 26.

At his death Mr. Giorno had been finishing a memoir, “Great Demon Kings,” which is scheduled to be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux next year. He said he hoped it would communicate the possibilities of a life radically open to art and to others. In a 2006 poem titled “Thanx 4 Nothing,” written on his 70th birthday, Mr. Giorno wrote:

May every drug I ever took

come back and get you high

may every glass of vodka and wine I ever drank

come back and make you feel really good,

numbing your nerve ends

allowing the natural clarity of your mind to flow free,

may all the suicides be songs of aspiration,

thanks that bad news is always true,

may all the chocolate I’ve ever eaten

come back rushing through your bloodstream

and make you feel happy,

thanks for allowing me to be a poet

a noble effort, doomed, but the only choice.