- Source: Art Agenda

- Author: Rahel Aima

- Date: January 6, 2021

- Format: Digital

SoiL Thornton’s “Does productivity know what it’s named,

maybe it calls itself identity?”

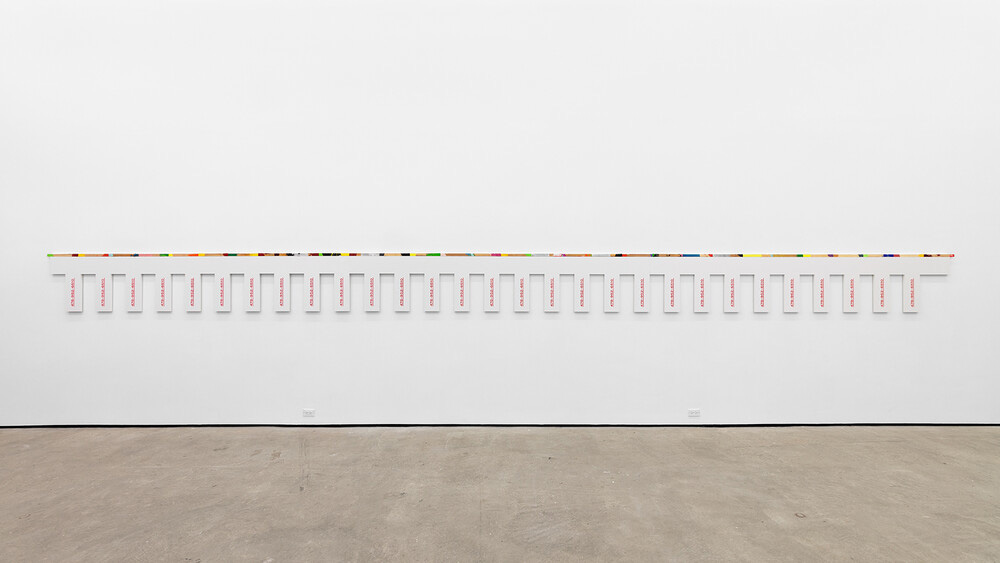

SoiL Thornton, Dematerialize now but as self portrait to whom (1990-2020 Labor Cont(r)act), 2020. Used paint sticks on wood and Formica with silk screen ink, 23 × 363 × 1 inches. Image courtesy of the artist and Essex Street/Maxwell Graham, New York.

In SoiL (formerly Torey) Thornton’s 2019 solo show at London’s Modern Art, a Macon, Georgia-area number was spray-painted across one corner of the gallery. In their current show at Essex Street, New York, the same number repeats on a crenellated Formica tear-off flyer, titled Dematerialize now but as self portrait to whom (1990-2020 Labor Cont(r)act) (all works 2020 unless otherwise stated), an oversize version of the kind you might see advertising piano lessons or rooms for rent. Used paint sticks along its top edge create an overall effect of a printer test page. But here, it’s the artist that’s for sale in one of the most frankly exciting shows I’ve seen this past year. Call them, maybe.

SoiL Thornton, Dematerialize now but as self portrait to whom (1990-2020 Labor Cont(r)act), 2020. Used paint sticks on wood and Formica with silk screen ink, 23 × 363 × 1 inches. Image courtesy of the artist and Essex Street/Maxwell Graham, New York.

In 2020, art institutions sought to offer a corrective to the historical marginalization of BIPOC artists. Or perhaps dealers are more interested in meeting the predictable uptick in market demand. In the aptly titled “Does productivity know what it’s named, maybe it calls itself identity?” Thornton unpicks this fetishization of identity and, as their diaristic exhibition text puts it, “biography as trap.” They wonder whether the cultivation of individual celebrity—especially one whose work is predicated upon their racial or gender identity—is a productive mode for artmaking, and how that subsequent work should be valued.

These questions are most overt in the delightful What Punk (2018–20), a heavy, oversize album of 52 JET magazine covers spanning 1979 to 2013. They feature famous Black women through the decades: Patti LaBelle (thrice) and Vanessa Williams, Mary J. Blige and Ashanti, Michelle Obama and Octavia Spencer, and so on. A star-shaped neon sale sticker affixed to one corner encourages the viewer to flip through the pages. Flagged Identity, meanwhile, considers the ways that we are interpellated by our financial identities which, in the form of credit scores, circumscribe both how and where we are able to live.

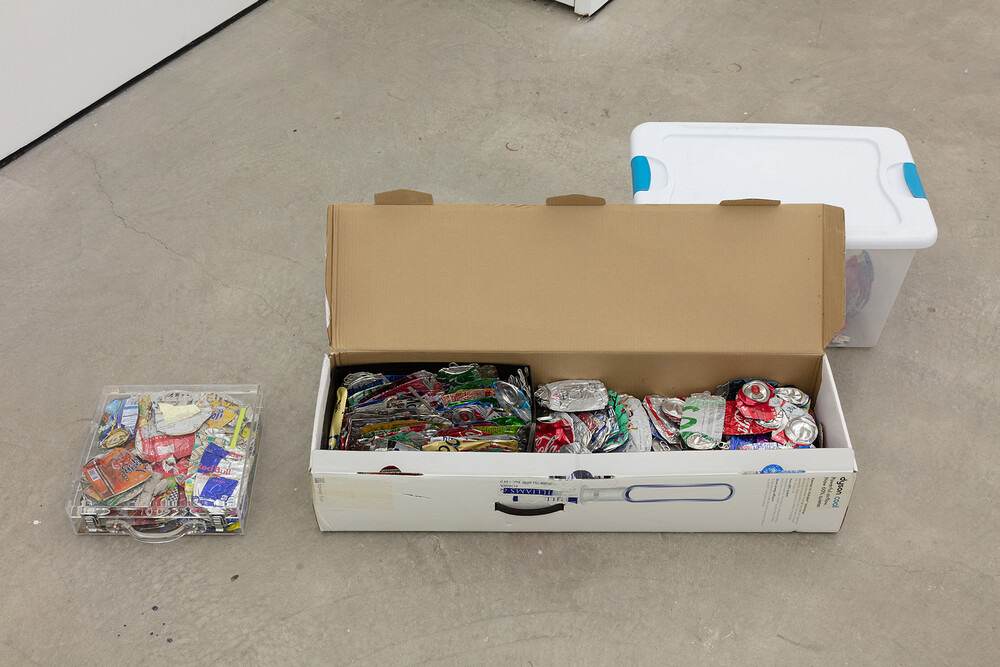

C-prints of Thornton’s inactive and active bank card chips—one suspects they would be rather pleased if their identity was stolen as a result of this show—are embedded in a mirror, along with a photograph of a young Black person with a paper bag over their head (the metaphor of color tests recurs throughout this show). And—have you ever examined one of these chips before? They suggest floorplans, but with curvy, bulging walls, the kind of domiciles that one imagines gnomes or other fairytale creatures might inhabit. On the floor nearby is Assisted Cleansing/tactile gap glue (289 of 1,000,000) (2020–ongoing), comprising “vehicularly flattened” soda cans in a cardboard box, storage bin, and, gorgeously, a Lucite briefcase. One imagines them pressed between the pages of a book, colorful urban bouquets.

View of SoiL Thornton’s “Does productivity know what it’s named, maybe it calls itself identity?” at Essex Street, New York, 2020/21. Image courtesy of the artist and Essex Street/Maxwell Graham, New York.

View of SoiL Thornton’s “Does productivity know what it’s named, maybe it calls itself identity?” at Essex Street, New York, 2020/21. Image courtesy of the artist and Essex Street/Maxwell Graham, New York.

The same themes are further intimated in Who’s dirt above the rest (Honeoye (HUN-e-oy) as one amongst other New York soils) (pre name change), which appears from afar as a rusty, pinpricked brown expanse. Up close, it’s pleasingly prosaic: a wooden panel painted brown into which star-headed screws have been driven, with little splintered rings at the sites of contact. Sometimes they are referenced in the titles which, like the exhibition text, insist on a Glissantian right to opacity, as with What is Sexuality, Is The Scale Infinite Similar To A Line (new modes of press and chromakey) (TT-ES-00022). Here, a large, elongated plus-sign of a quilted mattress hangs on the wall, its bottom edge a few inches from the floor.

This mattress is painted acid green and covered with messily glued NYC souvenir pennies. They have been smashed and elongated like coppery pizza dough but their landmarks are still legible: “Toys’R’Us, Times Square,” reads one. Best of all is the tag that flops from the work’s bottom edge, like a dog’s lolling tongue. I half expect it to declare This Is Where The Magic Happens! Instead, it announces that it is made by Custom Bedding LLC of Maplewood, NJ, and admonishes that “under penalty of law this tag not to be removed except by consumer.” One wonders whether the consumer is the artist or the collector here.

SoiL Thornton, Assisted Cleansing/tactile gap glue (289 of 1,000,000), 2020–ongoing. Vehicularly flattened aluminum cans inside storage vessels, dimensions variable. Image courtesy of the artist and Essex Street/Maxwell Graham, New York.

Older works by Thornton, not on view here, share the shape and upholstered effect of this work as well as part of the title—a recurring gesture—but appear with different colorways and adornments. At the 2017 Whitney Biennial, for example, the mattress was painted black and daubed with gold, bark-like flecks and strung with aluminum dog tags marked with A-Z and acrylic splotches. Considered alongside this new piece, the works suggest that sexuality is as mutable, and as contingent on presentation, as one’s perceived race or ethnicity.

Some titles feature simple one-liners, as in Chamber Orchestra (2018–20), a photograph of urine-filled water bottles all lined up on a sandy shore like a tinkly marimba. It is slyly positioned by the entrance next to stacks of the rather stream-of-consciousness exhibition text. Maybe I’m feeling sentimental about leaving the city after spending most of my adult life here, but this exhibition feels like a New York streetscape. The tear-offs, the ATMs outside bodegas that gouge you on withdrawal fees, the sloppily painted plywood, the can collectors, the schlocky pennies, the whole piss-soaked city.

SoiL Thornton, What Is Sexuality, Is The Scale Infinite Similar To A Line (new modes of press and chromakey) (TT-ES-00022), 2020. Acrylic paint, pressed smashed elongated pennies on cotton and foam with wood frame, 108 × 90 × 12 inches. Image courtesy of the artist and Essex Street/Maxwell Graham, New York.

SoiL Thornton, Every Good Body Does Fine (Membrane between granular pearl dive access), 2020. Twenty-six gauge stainless-steel on circa 1940s salon style bathroom stall door heart pine wood, 52 × 21 ½ × 2 inches. Image courtesy of the artist and Essex Street/Maxwell Graham, New York.

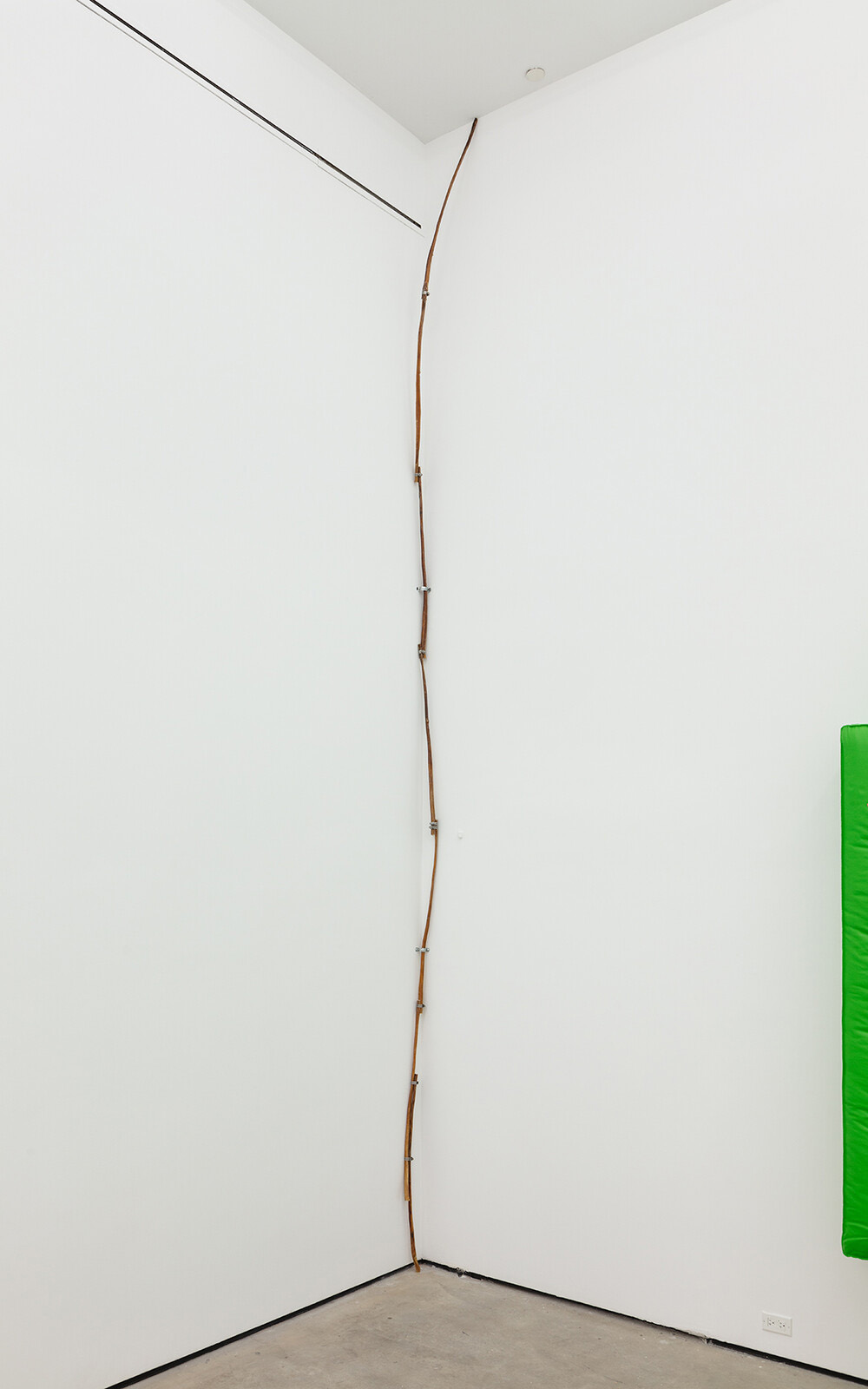

SoiL Thornton, False Spine (pillar), 2020. Bull pizzle (penis), plumbing pipe collars and hardware constructed to height of roof, dimensions variable (in this instance: 214 inches). Image courtesy of the artist and Essex Street/Maxwell Graham, New York.