- Source: New York Magazine

- Author: Ariel Levy

- Date: January 4, 2007

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

Chasing Dash Snow

Colen and McGinley, Snow, and Colen on the High Line. Photo: Cass Bird

The artist Dash Snow rammed a screwdriver into his buzzer the other day. He has no phone. He doesn’t use e-mail. So now, if you want to speak to him, you have to go by his apartment on Bowery and yell up. Lorax-like, he won’t come to the window to let you see that he sees you: He has a periscope he puts up so he can check you out first.

Partly, it comes from his graffiti days, this elusiveness, the recent adolescence the 25-year-old Snow spent tagging the city and dodging the police. “He’s pretty paranoid about lots of things in general, and some of it was dished out to him, but others he’s created himself,” says Snow’s friend, the 27-year-old artist Dan Colen, who—like so many of their friends—has made significant artistic contributions to the ever-expanding mythology of Dash Snow. Colen and Snow went to London together this fall for the Saatchi show in which they both had work. (Saatchi had bought one of Colen’s sculptures for $500,000.) Saatchi got them a fancy hotel room on Piccadilly. They had to flee it in the middle of the night with their suitcases before it was discovered that they’d created one of their Hamster’s Nests, which they’ve done quite a few times before. To make a Hamster’s Nest, Snow and Colen shred up 30 to 50 phone books, yank around all the blankets and drapes, turn on the taps, take off their clothes, and do drugs—mushrooms, coke, ecstasy—until they feel like hamsters.

If you want to find Snow, you have to find Colen, or Snow’s other best friend, the 29-year-old photographer Ryan McGinley, who four years ago became the youngest person ever to have a solo show at the Whitney. That show, “The Kids Are Alright,” depicted a downtown neverland where people are thrilled and naked, leaping in front of graffiti on the street, sacked out in heaps of flannel shirts—everything very debauched and drug-addled and decadent, like Nan Goldin hit with a happy wand. Part of what made McGinley so famous (like Goldin before him) was that he offered not just an artist’s vision of a free and rebellious alternative life but also the promise that he was actually living it, through photos that looked spontaneous, stolen, of an intimate cast of characters, a family of friends, and in McGinley’s case, of Snow in particular. In some ways, Snow has been his muse.

“I guess I get obsessed with people, and I really became fascinated by Dash,” says McGinley, who shares a Chinatown loft a few blocks away from Snow’s apartment with Dan Colen, whom McGinley has known since they were teenage skateboarders in New Jersey. The apartment used to be a brothel; for a long time, Chinese men would come to the door and be disappointed when McGinley or Colen answered it. McGinley shows me his photos of Snow over the years, dozens and dozens of them. Snow with cornrows, with a shaved head, with a black eye. There is one photo called Dash Bombing that was in the Whitney show: a shadowy shot of Snow out on a ledge, tagging a building in the night sky, Manhattan spread out below him. It’s an image of anarchic freedom, one that seems anachronistic and almost magical in this city of hermetically sealed glass-cocoon condo towers. It’s as if Snow were an animal—prevalent in the seventies, now thought to be extinct—that was spotted high over the city.

“I actually don’t like graffiti,” McGinley says. “I was just interested in the person that would write their name thousands and thousands and thousands of times. These kids that would go up on a rooftop, 40 stories up, and go out on a ledge to write their name—it’s just, like, the insanity of it all!” McGinley smiles his clean smile. “It’s funny to me that Dash has become like a rock star, but he’s so paranoid. That comes from graffiti culture—like, you want everybody to know who you are and you’re going to write your name all over the city, but you can’t let anyone know who you really are. It’s, like, this idea of being notorious.”

And because notoriety is crucial to something much larger than graffiti culture, Dash Snow is becoming a kind of sensation. Young people poured out onto Joey Ramone Place waiting to get into his last show at Rivington Arms gallery. He had a piece in the Whitney Biennial—a picture of a dog licking his lips in a pile of trash and several other Polaroids. You may not be able to find him, but you can hear his name, that zooming syllable—Dash!—punctuating conversations in Chelsea galleries and Lower East Side coke parties and Miami art fairs and the offices of underground newspapers in Copenhagen and Berlin, like a kind of supercool international Morse code. Because the art world loves infamy. Downtown New York City loves infamy—needs it, in fact, to exist.

Colen and McGinley in Dash's bed at Dash's apartment. Photo: Cass Bird

What makes the legend richer is that Dash Snow could very easily have lived a different kind of life, been a different kind of artist. Snow’s maternal grandmother is a De Menil, which is to say art-world royalty, the closest thing to the Medicis in the United States. His mother made headlines a few years ago for charging what was then the highest rent ever asked on a house in the Hamptons: $750,000 a season. And his brother, Maxwell Snow, is a budding member of New York society who has dated Mary-Kate Olsen. But Snow has concocted something else for himself. He has been living as hard as a person can—in and out of jail, doing drugs, running from the police—for a decade. He’s unschooled, self-taught. And in much the same way that Andy Warhol used the life force of young artists and assorted beautiful people to keep himself inspired, sharing his own talents and imprimatur in return, McGinley and Colen have adopted Snow as the mascot of their message.

Ryan McGinley wasn’t an artsy sissy growing up; he was a jock, and his green-eyed confidence is working on all cylinders. McGinley is the youngest of eight children of a father who worked for Owens Corning and a mother who goes to church every single day, and he’ll give you an answer to anything you ask. McGinley is big on family, community, and he is his scene’s court hagiographer. Instead of Warhol’s test shoots, McGinley took Polaroids of every person who would walk into the apartment he and Colen used to share on East 7th Street, a place that became locally famous in the nineties as somewhere to hang out and get wasted and be bad. People fall in love with McGinley’s work because it tells a story about liberation and hedonism: Where Goldin and Larry Clark were saying something painful and anxiety-producing about Kids and what happens when they take drugs and have sex in an ungoverned urban underworld, McGinley started out announcing that “The Kids Are Alright,” fantastic, really, and suggested that a gleeful, unfettered subculture was just around the corner—still—if only you knew where to look.

In actuality, McGinley is methodical, calculating, disciplined. He can barely drink anymore and follows a strict dairy- and sugar- and caffeine-free diet to reduce his tinnitus, a chronic ringing in the ears. One long wall of his apartment is lined with shelves on which he keeps his alphabetized collection of art books and binders cataloguing all of his work and Snow’s. “Because you never know what’s going to happen with Dash,” McGinley says and gets up on a ladder to pull down some of Snow’s old Polaroids.

There is a shot of Snow’s bloodied face: a self-portrait. “I think he jumped through a window? I’m not sure what happened that night.” Next is a photograph of a glorious girl grinning in a hat on the boardwalk. “That’s Dash’s wife, Agathe.” They married when they were 18, and Agathe, who is Corsican, needed papers to stay in the country.

“But Dash was totally in love,” Dan Colen tells me later. “They were like husband and wife for a long time, and they still have a really strong bond, as much as either one of them likes to ignore it or pretend or whatever. They were like the coolest couple ever.”

There is a picture of someone snorting a line of coke off an erect penis, and then one of Snow naked with an Asian girl wearing red ski goggles. “She must be a hooker because he’s wearing a condom,” says McGinley. Many of the same people are pictured in Snow’s photos as in McGinley’s early work, doing the same kinds of things, but Snow sees something very different. “I’m into freedom and a celebration of life, and Dash is more about the fall of humanity,” McGinley says. “Hells, yeah. He’s into some dark shit: S&M, crack, corrupt cops…”

McGinley and Colen met Snow when they were in art school (at Parsons and RISD, respectively) and Snow was 16 and living on 13th Street in Alphabet City and starting a graffiti crew called Irak (in graffiti slang, to “rak” is to steal, which they did) with a guy named Ace Boon Kunle, “a big, black homosexual,” as McGinley describes him, whose tag is Earsnot.

“Dash was like me, a polished derel”—a polished derelict, says Kunle. “He got that twinkle in the eye that lets you know. But Dash wasn’t like a lot of the derels I was hanging out with who would run out of stores with clothes in their hands. Dash would steal, but it’s the way you steal: I go in and I’m really friendly with the help and I’m smooth. I’ll make it sweet, so the next three or four times I come in the store, it’s all good with the help. Dash got really good at it. One of the things I always say is that a really good graffiti writer will make a good shoplifter—someone who’s used to breaking the law fifteen or twenty times a day.”

On a Manhattan rooftop. Photo: Cass Bird

Not everyone in their circle was comfortable with Snow’s vespertine prowlings. “Ryan and Dan, I understand their success, but Dash, to me? As far as I was concerned, he was just a vandal,” says Jack Walls, an artist and writer whom Snow, McGinley, and Colen all refer to as a father figure and who was for many years the boyfriend and sometime subject of Robert Mapplethorpe. “There would be times I’d be hanging out with everybody drinking and Dash would go off into the night and I would be so worried about him falling off a bridge. I would just stand there watching until he was out of sight, wondering if I’d ever see him again.”

Walls met Snow one day when he was walking down Prince Street with Patti Smith’s son Jackson. “It was wintertime, and there’s this kid. He went out of his way to say hi to me. Jackson said, ‘That’s Dash, I went to school with him.’ At the Little Red Schoolhouse. And then later I was at Ryan’s and I was looking at his Polaroids and I said, ‘Who is this? What’s his story?’ Ryan said, ‘That’s Dash; he does graft.’ ”

Snow and Irak crew were always pissing people off. They used to pay bums to let them tag their backs. Another crew member named Simon Curtis got his group into trouble with the police when he drunkenly stole a topless photograph of a girl he was obsessed with from a gallery opening in Williamsburg. Two of the gallery’s owners chased him, and depending on whom you ask, one of them either jumped or was yanked into the getaway car, and the other ended up clinging to the hood as the driver sped down the street and eventually got out to punch him. McGinley was in the passenger seat, taking photographs. Curtis went to jail. McGinley was arrested but wasn’t charged—as usual, he was near the center of the action, turning it into art, one step removed from the danger. “When it comes down to it,” says McGinley, “Dash is wild, a wild kid. I have my moments? But for me, it’s always sort of about creating a fantasy. It’s, like, the life I wish that I was living. For Dash, it’s really the life.”

Snow was sent to juvenile detention when he was 13, and since then he has lived on his own and shunned his wealthy family. His friends are the ones who encouraged him to make the transition from thief to artist. Of course, rebelling against your famous art family by becoming a famous artist is a pretty interesting way to rebel.

“I think Ryan and I are blatantly ambitious, and we didn’t come from a place where we could coast by, by any means,” says Colen. “We had to make money for ourselves, and we had to figure out how to do it. And neither of us could really do anything except make art. The reason I’m not including Dash is that he more stumbled upon art, whereas Ryan and I pursued it.

“Dash started doing some things that were kind of like art, and Ryan and I used to encourage him. I used to have these long talks with him because he grew up in this art family and he met a lot of crazy people, but he was a little ignorant about stuff. He had all these weird, really amazing opportunities, like he met Robert Rauschenberg when he was 5, but maybe he didn’t know who Matthew Barney was. Me and him spent like a lot of time really late at night just talking about it.”

Colen says he introduced Snow to his former gallerists Melissa Bent and Mirabelle Marden at Rivington Arms (Colen has since switched to Peres Projects) and urged them to take on Snow, “which was, like, a bit of a struggle.” (“I’m sure Dan probably thinks he started the whole fucking gallery,” says Bent.) In any case, Snow refused to call himself an artist for a long time. He used to boast that he’d been Polaroiding his night wanderings since he stole a camera at age 13, just so he’d know where he’d been when he sobered up. More recently Snow has been into collage, but either way some see in his work a kind of radical authenticity that parts of the art world are desperate for. “Whether it’s total bullshit and he’s running around trying to get in trouble with the police, it kind of doesn’t matter,” says art agent and consultant Molly Logan. “As a case study, here’s a creature who’s just reacting. I think that for the last five years or so, there is a larger desire for the personal: something that has the hand of a person in it. It’s not I’m going to do this so people will think I’m crazy. I am crazy! I think he’s genuinely and completely self-destructive.” Which is, of course, what the art world has always wanted, especially in New York City, what Jackson Pollock or Willem de Kooning supplied, along with genius. That magic flash of insanity, framed and for sale.

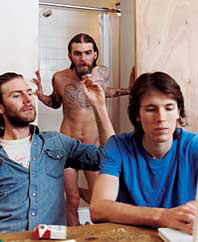

Dash coming out of the shower

at McGinley and Colen's apartment.

Photo: Cass Bird

“Even if Dash doesn’t call it art, his stuff is just amazing and unique regardless,” says Colen. “It’s just like…him.”

The first time I laid eyes on Dash Snow he was bearded but beautiful in a platinum wig and an off-the-shoulder gold-and-purple-sequined sheath. It was Halloween, and everyone was smoking cigarettes at an underground bar near Washington Square Park at Courtney Love’s book party. Snow seemed cokey and amped up. Everyone who came up to greet him kissed him on the mouth, some of the girls with tongue. McGinley was wearing a homemade bear’s head and seemed eager to introduce me. “Hey,” said Snow, and became palpably paranoid. Soon thereafter he leaped out of his seat. “Okay. Let’s go back to my apartment. Just you and you and you and Dan,” he said, as Colen ambled up drunk as hell. Dan Colen is so tall the top of his head almost grazed the ceiling. His denim shirt was unbuttoned very low, and his eyes were bloodshot blue. “You can’t come,” Snow said to me. “I am not about trying to be rude. Do you smoke? Have a cigarette. I am not about being rude. But there may be illicit activity and you can’t be around. No, no. No, no, no. Maybe you can come by next week.”

But next week passed. And then another. Then one day the phone rang and it was McGinley, asking if I could be at an address in fifteen minutes. Snow and McGinley were waiting for me out on the fire escape in the gray sky above Bowery. Because of the butchered buzzer Snow had to come down to let me in. He greeted me with a hug and a kiss, as if it were his moral obligation to be affectionate even with someone who makes him feel edgy and on guard. Snow has long, greasy blond hair and a bum’s beard and, as always, he was wearing tight black jeans, a ripped T-shirt, and a black leather Martin Margiela vest he’d scored from a fashion shoot. He looked like the son of Jim Morrison and Jesus Christ.

Inside the apartment, there was no furniture but crap everywhere: an upturned chair, a mirror detached from a bureau, a broken guitar, scissors, a giant dollhouse. “It’s not a dollhouse, actually,” said Snow. “I liberated that from a community garden, stole it. It’s for birds.” On the wall were beautiful, ghostly amoebas on yellowed-paper backgrounds. “Those are spit circles,” said Snow. “I was sick, and I’d just wake up with a chest full of phlegm and spit all over the paper and make circles, you know? I’m not quite sure what I’m gonna do with those yet, but I like the way they’re coming out.”

McGinley was lying on the floor next to stacks of the New York Post and the Daily News with words and pictures cut out of them. “I’ve always been a big fan of the Post, and I remember in 1992, or whenever the fuck it was, Desert Storm, the Gulf War? Remember? I’d always read the Post, and there’d be really rad headlines about it,” said Snow. “I was just down for it! I’m down with anyone, even if they’re bad people, if they’re just, like, anti-American, you know what I mean? This is a series I’m working on,” he pointed at some collages on the wall with lots of pictures of Saddam Hussein, whose likeness is also tattooed on Snow’s arm. “They’re old headlines, and they all have come on them. Yeah, mine.”

Snow has been working with his own ejaculate a lot lately; his contribution to the Saatchi show was a piece called Fuck the Police, which featured sprays of his sperm on a collagelike installation of tabloid cutouts, headlines about corrupt cops.

McGinley and Snow shared a Budweiser and passed a cigarette back and forth. “Yo, look at that picture of Agathe over there,” said Snow. “This picture is completely rad. She doesn’t have her top teeth yet. The reason I fell in love with her is she was just like a pirate, you know? We’d go at night and walk through subway tunnels together. We’d be on the platform; I’d say, ‘Come on, let’s walk to the next station.’ We would come out covered in soot. She was just down!”

I asked where Snow spent his childhood.

“All over,” he told me. “Different places in Manhattan. But, uh, I don’t know, I got in a lot of trouble. I won’t get too deep into this one, but I was in a juvenile-detention center from 13 to 15—like, two years?” He was guilty, he said, of being a free spirit. “And then I came out, and from 15 on, I was just on my own.”

Rebelling against your famous art family by becoming a famous artist is a pretty interesting way to rebel.

I asked Snow if, instead of stealing, he could have gotten money to live from his grandmother Christophe De Menil, who lived in a magnificent carriage house she had redone by Frank Gehry and Douglas Wheeler, with a swimming pool on the ground floor. “Probably,” he said. “I never asked. I do my own thing.”

“But Dash’s grandmother is the best…” said McGinley.

“I see her here and there,” Snow interrupted.

“She’s always taking care of us…”

“Getting us drunk,” said Snow. Snow said he has no contact with his parents. “Cut off. Scumbags.”

But as it happens, this isn’t quite true. There was a giant photograph on the wall of a man snorting cocaine, and it’s Chris Snow, Dash’s father; I recognized him from one of McGinley’s binders.

“Well, yeah, I like him, we just don’t talk that much,” Snow said when I asked about it.

“You do talk to your dad!” McGinley shouted. “We’ve all hung out with your dad!”

Snow thought for a minute, then revised. “Recently, my dad and I got back in touch,” he said. “He’s awesome. During the seventies, he was just on his own and then he joined a traveling medicine man on the West Coast doing peyote. He’s a weirdo. I remember at one point he was living with this Native American woman? And they had, like, white doves flying around their apartment shitting on everything. We got tattoos. He got Snowman 1 and I got Snowman 2,” he said, and showed me his arm. But he really doesn’t speak to his mother, Snow said. Ever.

He picked up a human skull from the floor. “Look at how scary that is, man. I can’t believe that … it’s so creepy. I’m going to do a come-shot series on the faces of the skulls, but after I come on them, I’ll throw glitter on them to make it pretty. Hey, look, he’s missing the same tooth as you, Ryan,” said Snow, and poked his finger into the empty space in the skull’s mouth.

Then he told a long story about how eight cops chased him across Highway 101 in Los Angeles, and beat him up when they caught him. “They forced me to my knees, they’re slapping me and shit, saying, ‘Where are your friends? You long-haired faggot, you’re pretty manly for a bitch!’ ” He was sentenced to community service, cleaning up L.A.’s skid row. “It was such a fucked-up dope neighborhood, crack neighborhood, and people just take shits on the street, and I would have to power-hose it off. I would clean out all these fucking things with a bandanna over my face, and I would take my lunch break and come back and every spot, all the corners, were all filled with shit again. They’d be laughing at me because they knew; they’d go shit there again the second I fucking go to have some food.”

There were a lot of stories like this—Snow baiting and then evading the cops, cracking heads or getting his head cracked. He has made himself believe that he is pursued by the police, that they are obsessed with him, and not the other way around. Snow is an electric and funny storyteller, but there can be something a little unpleasant about his relentless commitment to criminality: Dash Snow, Liberator of Birdcages.

Snow took us into his bedroom to try to find some Polaroids from California, and McGinley put on his parka and lay down on the mattress. There was very little white wall space; Snow covers almost every inch with clippings and posters and photographs and sketches. Snow had a girl named Jade over here the previous night, and he pointed out where she wrote her phone number on the bottom of one of his bookshelves. I asked him if he was in love.

“I kind of am, actually.”

“You’re in lust!” said McGinley.

“Whatever, man. I haven’t been psyched on someone in a long time. I met this lady, and I told her I wouldn’t leave the party without a kiss. She’s rad. Lemme use your phone?”

“Make it snappy, Happy,” said McGinley and passed it to him.

“There’s no feeling like that: when you’re psyched on somebody. Like this morning? I woke up smiling.” Snow left the room to make the call and returned triumphant. “She’s coming over, and we’re going to take a bath.”

He lay down next to McGinley and produced some photos of the London Hamster’s Nest, all of which featured Dan Colen’s impressive penis and two naked girls.

“Dan’s a grower and a shower,” said Snow, and got into the parka with McGinley so both of their heads were inside the hood. There is a physicality between these guys, in their photos and in life, that you usually only see among little kids. That McGinley is gay makes no difference to avidly straight Colen and Snow: They don’t care about sexual orientation, they care about sex.

“The point of the Hamster’s Nest…”

“It’s not like you break anything. It’s just really a task,” said Snow.

“Well, but then you do as many drugs as you can do within the Hamster’s Nest and you really try to be a hamster,” said the other head in the hood.

“It’s just about making your own world!” Snow declared. “And then you get naked.”

I pointed out that hamsters don’t do drugs.

“Hamsters,” said Snow, “are animals.”

Jade was on her way over, so we left. It was nighttime, and all the chandelier shops on Bowery sparkled in the dark. “Isn’t this amazing?” asked McGinley. “I mean, isn’t this, like, the most beautiful thing?” He started walking the short distance to his loft. “The thing is, it’s fun to be an outlaw and everything, but if I were a cop? And I had to chase some kid across the 101? I’d fucking beat the shit out of him, too.”

Dominique Schlumberger, a French heiress with fortunes in the textile and oil-field markets, met John De Menil at a ball at Versailles. They were married in 1931, when she was 22 and De Menil was 27. Upon returning from their Moroccan honeymoon, they commissioned Max Ernst to paint Dominique’s portrait and rode on horseback down the Bois de Boulogne. It was a grand life until the Nazis invaded France, at which point Dominique fled Paris for Cuba with her children; the eldest, Christophe, had chicken pox. Decades later, Christophe De Menil married the Buddhist scholar Robert Thurman long before his second wife gave birth to the actress Uma Thurman, and the couple had a daughter together, named Taya, who is the mother Dash Snow refers to as a scumbag.

But some important things in the art world happened along the way. The De Menils ended up in Houston, where they started collecting important works by Léger, Matisse, Cézanne, Braque, Picasso, which they kept in the vast home they had designed by Philip Johnson. The radical European collectors stood out in Texas, and they had the politics to match. The De Menils regularly invited black guests to dinner during the era of segregation. They attempted to give a sculpture called Broken Obelisk to the city, but Houston refused their condition that it be dedicated to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (It sits in front of the Rothko Chapel, also financed by the De Menils.) When John died, his funeral was attended by a local contingent from the Black Panther Party.

In her lifetime, Dominique was regularly listed in Forbes magazine as one of the 400 richest people in America. After the war, the family would return to France from time to time, to Val-Richer, the Schlumberger family estate in Normandy, a renovated eleventh-century abbey. “Each branch of the Schlumberger clan has a wing,” Dash Snow’s grandmother Christophe De Menil told a reporter in 1986. “It gives us a strong family feeling.”

In fact, it was Christophe who first became interested in modern art and encouraged her parents to become collectors. Over time, she and her four siblings would use their enormous wealth to promote the arts: Christophe’s sister Philipa De Menil concentrated the bulk of her inheritance in the Dia Art Foundation, which she founded with her husband in 1974. Dia funded, for example, Donald Judd’s majestic installation in Marfa, Texas, and Walter DeMaria’s Lightning Field in New Mexico.

Christophe De Menil still works with the family’s museum in Houston; in addition, she designs costumes for Robert Wilson and has supported many dance greats and performance artists, like Twyla Tharp, Philip Glass, and LaMonte Young. She loves art, but she does not love to speak about her oldest grandson. “It is very bad for Dash to be associated with the De Menils,” she says when I call her. “Because people feel, oh, he is leaning on it or that it is like putting a title to your name, like using baron.” I point out that if you are writing a story about an artist, you really have to mention that he comes from the single greatest art family in America. “You don’t have to! You want to!” she shrieks. All De Menil will admit about Snow is that “it’s true that we love art and we look at it together and we advise each other.”

Everyone is extremely secretive and confused when it comes to Snow’s relationship with his family, Snow most of all. (A good myth needs a little mystery.) Friends say they think Dash Snow reminds his mother of her wild former husband, Chris. They say she lies and lets him down. But nobody can produce a grand crime, a compelling explanation for Snow’s contempt. “It’s upsetting, but they don’t talk,” says Colen. “I probably shouldn’t have said anything. Dash actually told me he was really upset at you because you called his grandmother or something like this.” Snow wondered how I was able to find her, whether I had government connections. (I looked her up in the phone book.) “Yeah, he’s really crazy,” says Colen and offers to call Snow up so we can straighten it out. Colen finds him—at Christophe De Menil’s—but Snow won’t come to the phone.

Dan Colen grew up in Leonia, New Jersey, but his whole family is from Brownsville, in Brooklyn, and you can hear a little of it in his vowels—a Jewish Mickey Rourke. Colen’s first studio was in his grandfather’s abandoned junk shop near Coney Island; his grandmother was once arrested for using slugs to try to get through a subway turnstile. (She tried to convince everyone they were Puerto Rican quarters.)

“When it comes down to it,” says McGinley, “Dash is wild, a wild kid. I have my moments. But for me, it’s always sort of about creating a fantasy. It’s like the life I wish that I was living. For Dash, it’s really the life.”

Colen’s most famous painting is called Secrets and Cymbals, Smoke and Scissors (My Friend Dash’s Wall in the Future), which is a three-dimensional painting of Snow’s wall with intricate renderings of all the headlines about police brutality and Saddam Hussein that Snow collects and tapes up, on a Styrofoam sculpture of a wall. When I am at his studio, Colen shows me one of his first art projects in high school: a series of magazine pictures of hip-hop stars on which he ejaculated. “I probably didn’t like the assignment,” he says and snorts. “Yeah, Dash stole jizzing from me, but I got to paint his wall.”

Colen caused a massive controversy in Berlin in September, when he and his friends put up flyers all over the city to publicize his show “No Me,” picturing Colen from the neck down, a tallith (Jewish prayer shawl) hanging from his erect penis. “As I tried to interpret it and explore my son’s psyche,” says Colen’s father, Sy, who has spent a good part of his life raising money for Israeli groups, “it seemed to me certainly the Holocaust is an event that he knows about; he knows that our family lost 25 relatives, and in a country that killed 6 million Jews, what Dan was saying was that this is our future. The penis for him, it’s something sacred. It is the staff of life.”

Sy Colen says he’s very grateful for all that McGinley has done to promote his son’s career. “When I was a kid and I went from Brooklyn to Manhattan, it was a big trip: Theirs is a different world.”

Snow brought his new girlfriend, Jade, to Sy Colen’s house for Thanksgiving. “Dash has long hair, but I’m accustomed to that. But it’s difficult to know who Dash is. You really have to work at it.”

If you were going to hate these guys, here’s how you would do it: You could hate them for using the word artist so frequently and so shamelessly. Or you could hate Snow for coming from money—mountains of it!—and being a cop-taunting, Saddam Hussein–fetishizing petty criminal. If you are an aging punk, you could hate Snow in particular for going over old ground and thinking it’s something new. (Iggy Pop puked on his audiences a long time ago.) Or you could hate all three of them for being so enamored with penises and what comes out of them. How much talent does it really take to come on the New York Post, anyway?

“But remember, they are at the phase in their career where they have to get people’s attention,” says Jack Walls. “I wouldn’t be surprised if in the next few years their work becomes shockingly sedate.” McGinley’s new show at TEAM gallery is all photographs of Morrissey concerts, for instance—fans’ faces hit with heavenly beams of stage light, aching with the orgasmic joy of idol worship. “See, that’s how Robert was able to get away with those flowers,” Walls continues, “because you’d see those and know all of what came before.” So when you looked at Mapplethorpe’s tulips, some flaccid, some erect, in the back of your mind you saw all the genitals he’d photographed; a serene cloud of baby’s breath invoked a spray of pubic hair, and suddenly you were thinking about perversion and propriety and society and all the while looking at a harmless black-and-white photograph of a flower.

Still, hating them has more advantages than respecting them. Because if you were to get caught up in the insanity and the creativity and the ridiculousness of their world, it could mean certain things. It could mean, for example, that it isn’t just that you were born at the wrong time. That maybe this city has still got it going on, antiseptic as it can seem. That the wild life is still out there for the taking, and the only difference between them and you is that they’re taking it and making something out of it.

But you can hate them if you want to: It’s easy. “I remember looking at the Whitney show and really resisting those photographs because of all the hype,” says McGinley’s gallerist, Jose Freire. “It would have been easy enough for him to continue what he was doing: I have my camera; I’m in this scene. But to see the work develop so much in such a short period of time … he seems so off-the-cuff, but it’s really surprising to discover he has incredible rigor. I don’t know if the scene he’s a part of is interested in that at all.”

Snow’s work, for instance, is regularly trashed for being slapdash: a salad of Dada and psychedelia with sperm dressing. But at their best, his collages have a special, specific feel; as if Snow pulled the papers and backgrounds out of a flophouse on Haight Street in 1969 and has somehow magically updated the headlines. His compositions invoke a world you’ve seen pieces of but never all together. “I look at Dash’s work and I think of Joseph Cornell,” says Freire. “Not the ideas: I think the ideas behind the work are all fucked up. But there’s a handling of the materials that might mean that there’s a poet trapped within him.”

“There’s a Tinkerbell quality to him,” says Molly Logan. “You feel like his work is the only thing keeping him here. He’s just hanging on and … that’s it. If that’s not there, there is no Dash.”

At Art Basel Miami Beach, the hangover seemed to start before the party even began. It’s partly a function of where the art world is now, pumped full of cash, desperate for the next young thing to swallow whole. There were $13 drinks in plastic Dixie cups. Civilians feeling unworthy and asking dealers things like “Can I ask you—and if it’s too vulgar a question, just say so—how much is it?” ($90,000). Layers of hierarchy and constant status checks: whether you can get into the after-party or the collectors’ lounge or the VIP collectors’ lounge, the Delano at 8 p.m. or the Delano at 1 a.m., and on and on and on until you want to blow your own head off. An orgy of networking and commerce and cocktails.

It was a warm night and McGinley took me to a dinner that Mirabelle Marden and Melissa Bent were giving at the opulent home of one of their artists. Teeny-tiny sprinklers sent circles of waves across the aqua surface of the blue swimming pool. McGinley was squiring around Alexandre Melo, the cultural adviser to the government of Portugal and the chief curator of the Ellipse Foundation, who just acquired twelve of McGinley’s photographs. Melo had noticed Jay-Z and Beyoncé looking at the gallery booths that day. “It’s good for the artists,” he said.

“Not really,” said McGinley. “People will sell to him because he’s Jay-Z, but then he’ll get tired of art and flip everything at Sotheby’s.”

“No,” Melo replied. “It’s more interesting to have people from different backgrounds collecting, not just old rich people.”

“You’re right, you’re right. There’s just something about celebrity culture that freaks me out.”

Next, we went to an address on Michigan Avenue, where their friend, the artist Nate Lowman, had curated a show with pieces by Colen and McGinley and Snow. Lowman was ducking in a corner trying to avoid being spotted by someone. “Vonce Nate Lowman started to burn mark the ceiling ov ower gallery,” said Hans Ulrich Obrist, a director of London’s most prestigious gallery, the Serpentine. “It vas very exciting!”

And there was Dash, sitting by the bar in a black top hat, clinging to Jade, a lean girl with long, wavy hair. He was still mad at me for calling his grandmother, but he gave me a long hug. I asked him to point out which piece was his, and Snow said, “It’s fucked up. They were supposed to send something, but it never showed. I have a piece in the fair, though. Wherever those Rivington Arms girls have their thing.” He didn’t seem to care. From the looks of it, the only thing Snow did care about was staying in close physical proximity to Jade at every moment. Jade waved at Hope Atherton and rifled through her quilted Marc Jacobs bag, but mostly she just sat on the steps, holding Snow’s hand and looking dazed and foxy.

Though Snow had told me that they never speak, his sister, Caroline, was on hand, talking with Agathe, who seemed drunk and a little sad. Caroline had an Irak sticker on her leather jacket, and her face was covered in strange, sloppy yellow makeup and pink eyeshadow. “I’m an actress, you know,” she said and kicked a long leg in the air, on which she wore black La Perla stockings that laced in tight X’s up the back of her calves. “But my brother is an artist.”

Kunle was there, too; a camera crew making a show about him for the Sundance Channel trailed his every move. A little white kid in a baseball hat came up to him and Kunle said, “You had a smart mouth, and that’s why you got smacked the other day. I’m Earsnot and you’re Naw: Don’t forget it.” Simon Curtis, out of jail and in a tie-dyed T-shirt, laughed at this.

The night went on and on for hours, from one club to the next to the next. At one point, someone yelled from a crowd in front of the Shore Club, “There goes Ryan McGinley, the famous artist. He gets more famous every day!” McGinley ran into one of his mentors, Jack Pierson, at a party in a penthouse staffed by topless men and women. He got a call from the Canadian filmmaker Bruce LaBruce, who wanted to meet up at a gay club. But McGinley was leaving for Japan in the morning, and at a certain point he’d had enough and wanted to get food.

McGinley sat in a red-leather booth drinking lemon tea, the 5 a.m. light on his pale cheeks. “So what do you think went down with Dash’s mother anyway?” he asks me. “He’s never told me. Who knows, maybe someday he’ll pull a My Own Private Idaho and go after the money. I doubt it, but you never know. Dash, you know … Dash Snow is a man of mystery.”