- Source: The Brooklyn Rail

- Author: Nicole Miller

- Date: May 2019

- Format: Digital

The Drowned World

Selections from the Dash Snow Archive

Installation view: The Drowned World: Selections From the Dash Snow Archive, Participant Inc, New York, 2019. © Dash Snow, Courtesy the Dash Snow Archive, NYC. Photo: Mark Waldhauser.

I first came across the name Dash Snow when I was trying to understand why François de Menil—an heir to the Schlumberger oil fortune, whose parents established one of the largest private art collections in the world—had provided a private jet for Texas Democratic Congressman Mickey Leland to meet with Fidel Castro in 1979. The purpose of the meeting was to arrange the release of four American prisoners, which the Cuban President did later that year. What I wanted to know was: Why had de Menil been involved? The Houston family—art patrons often compared to the Medici—also invested in liberal politics, backing civil rights leaders, antiwar activists, and liberal politicians. The de Menils helped launch the career of the young Black activist Mickey Leland, grooming him for the national stage and demonstrating a commitment to social reform.

For me, the story of the family’s civic engagement illuminates a moment in time when the face of progressive politics was liberal money doing good. No one asked where the money came from or challenged the logic of a money monoculture. In the same way, the work of Dash Snow—son of François de Menil’s niece—appears to me fixed in its historical conditions. Snow was born in Manhattan in 1981, at the dawn of the Reagan administration and the beginning of a period of corporate expansion and economic growth in New York City. Rejecting his uptown pedigree, Snow became a fixture downtown—a tagger, shoplifter, and reckless obsessive. Snow’s DIY ethos was embraced by high profile collectors, curators, and museums. His photography and installations were exhibited during the 2000s at the Brooklyn Museum, Deitch Projects, the 2006 Whitney Biennial, as well as internationally.

Though he forcefully disavowed his family, it’s hard to talk about Snow’s work or his countercultural stance without considering the culture he inherited. The Drowned World: Selections from the Dash Snow Archive, presented by PARTICIPANT INC with the Dash Snow Archive ten years after his death, positions Snow’s gutter-punk antagonism as continuous with earlier punk insurgencies on the Lower East Side and catalyzed by 9/11. This exhibition includes Snow’s collages, assemblages built with stacks of books, newspapers, or cigarette butts, handmade zines, Super 8 films, and a large selection of Polaroids that reveal the antic collisions and grim wit of the self-styled outlaw.

In interviews, Snow was often evasive or vague, but his photographs have the fluency of a nightly ritual. Laid out in a grid inside a glass case, the Polaroids graphically serialize “the shock treatment of urban life,” as downtown iconoclast Tina L’Hotsky put it in 1978. Snow’s urban vernacular elides evidence of gentrification in Giuliani’s New York. You could almost mistake his street-scenes, storefronts, signs, and shots of his graffiti crew for the landscape of the bad old ’70s. Indoors, the camera finds bodies tangled or bloodied, fucked up or strung out. The artist’s infant daughter also appears, along with intimate scenes of his partner, Jade Berreau. We get a glimpse of Snow’s habits and practices in the walls of his apartment, collaged with cutouts, and his floors covered with newspapers and books, which he deconstructed with an anarchist’s zeal. These Polaroids feel forensic—evidence of Snow’s obsessions and compulsions, appearing after a trauma or crime.

His large-format, black-and-white C-prints have the eerie composure of Warhol’s car crash series. His bodies lie prone or sit slumped in a bathtub or on a stoop. In Newspapers 1 (2006), a man in black Converse sneakers lies as if crucified on the ground, covered in copies of an LA newspaper. The papers reference the dereliction of a Bowery bum or the decadence of a pile of cash or the overwhelming surfeit of the news cycle. The same man appears in a companion image, curled as if asleep atop a row of newspaper vending machines. Again, the man might be a delinquent—but what catches my eye is the blurry cover of a magazine inside its display case. Printed on the cover is ”The Apprentice”-era face of Donald Trump, grinning like an apparition from the future. While the man sleeps, something sinister gathers in the darkness around him.

Although Snow’s images appear to be caught on-the-fly, this pair of photographs is visibly staged, suggesting that Snow understood his work in relation to performance. “He started pretty quickly creating these kinds of performances around him, where it would feel organic, but then you’d realize afterward that he had this ability to direct the situation without it ever feeling like a photo shoot,” his friend, artist Hanna Liden, said in a 2015 interview with the New York Times.

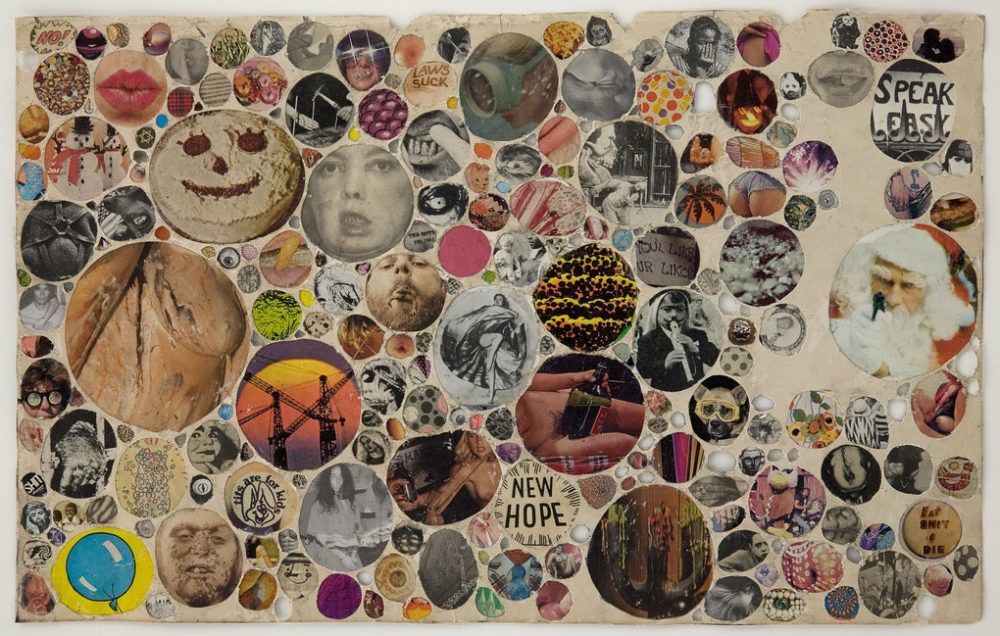

Dash Snow, Untitled (The End of Living...), 2007. Collage. © Dash Snow, Courtesy the Dash Snow Archive, NYC.

The impulse to shape the ephemeral is evident in Snow’s collages as well, which combine headlines from the New York Post or blend images of human body parts with handguns and toys. Though they might allude to the mashups of digital culture, the works on paper instead bring to mind the photomontages of Hannah Höch or the Surrealist assemblage of Hans Bellmer. They display his skepticism toward institutional forms of authority, from the penal system to the macho conventions of American sports. His mixed media assemblage Untitled (Sweet Thing) (2006) overlays a check in the amount of seven dollars and fifty cents, issued by the State of New Hampshire for “Bail return,” with bits of paper and other detritus—a guitar pick, a pocket knife. The piece appears as a punk emblem or badge of alternative value. It serves as evidence of the artist’s private logic, which—though pursued in the company of others—remains sealed from public or social exchange. For this reason, Snow’s memes and performances give the impression of an anti-social media.

In 2005, when filmmakers Aaron Rose and Joshua Leonard asked Snow about the responsibility of the artist to comment on political life, Snow shrugged: “It’s not really gonna do anything, you know? It’s not gonna change nothing. George Bush blew up the fucking World Trade Center so we could go rob them for oil and massacre children.”

As an instigator and chronicler of his scene, Snow is often compared to photographers Larry Clark and Nan Goldin. I wonder, if Snow had lived beyond the age of 27, whether he would have developed a richer vein of activism or critique. Would he, like Goldin—an opioid-crisis activist who has staged demonstrations to protest the ties between art institutions and the Sackler family, which owns the pharmaceutical company that makes the painkiller OxyContin—be causing a scene at the Met? Could he mount a persuasive critique of the institutional hypocrisies he seemed to loathe—perhaps interrogating his own family’s role in the global grab for oil?

He inherited a world where his family’s liberal investments were confounded by the doctrines of Cheney and Bush and the tautologies of the war on terror. From Snow’s point of view, neither revolution nor reform stood a chance. His work has the jittery, apprehensive mood of a manifesto—and like all manifestos, it performs its own powerlessness.