- Source: LOS ANGELES TIMES

- Author: SHARON MIZOTA

- Date: AUGUST 16, 2019

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

For these 20 women artists, ‘Rapunzel’ and ‘Dyketactics’ are just the beginning

In the show “Please Recall to Me Everything You Have Thought of” at the L.A. gallery Morán Morán, artist Eve Fowler brings together 20 female artists in the later years of their careers. The show’s title comes from a text by Gertrude Stein, whose writings Fowler has explored in her own work. It’s a polite, if unreasonable request — who can recall everything? Still, it speaks to a hunger for artistic and cultural inheritance. If these are our foremothers, we want to know as much as they are willing to share.

The show seems to organize itself around at least two themes: the sensate body and the rigors of geometry. Exemplifying the former are three works by the venerable Barbara Hammer, a pioneer in representing lesbian sensuality, who died this year. Her black-and-white photographs of female nudes in natural settings, taken in the early 1970s, are disarmingly frank but also hark back to a long line of art historical representations of women in nature. Her film “Dyketactics” from 1974 (here presented in a video transfer) uses dreamlike double exposures and hazy golden light to capture similarly prelapsarian moments.

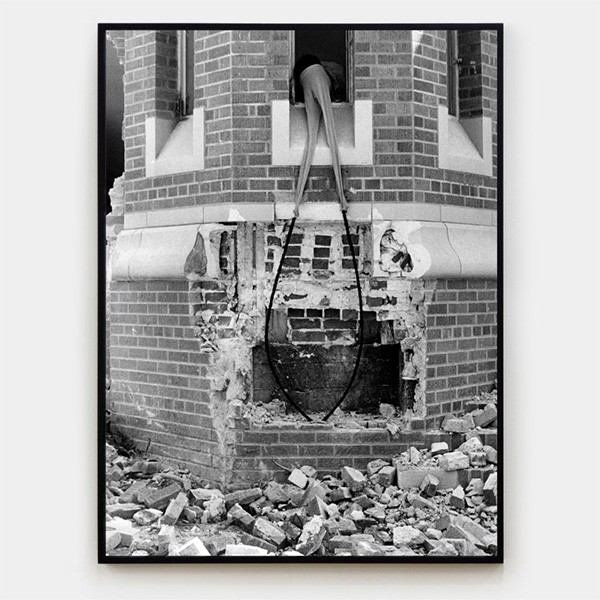

Another standout is the 1981 photograph “Rapunzel” by Senga Nengudi, better known for performance and sculptural works that use stretched and twisted textiles to refer to the human form. A woman, her face covered by a pair of nylons, leans out of the first-story window of a dilapidated building. The legs of the nylons stretch downward, ending in two dark braids that graze the rubble below. As Hammer’s work reframes the pastoral tradition through a contemporary lens, Nengudi recasts the European fairy tale as a futile fantasy.

Alongside such figurative works, Fowler has included many that are resolutely abstract. Harriet Korman’s “Untitled” from 2016-18 is surprisingly engaging despite its conventional format. It’s a rectangle divided into four quadrants, each filled with colored stripes. But unlike a lot of hard-edge abstraction, the stripes vary serendipitously in width and intensity. It’s an unruly grid that seems to pulse and shift before one’s eyes.

Maren Hassinger’s photograph “Whole Cloth,” from 2017, weaves the sensuous and the abstract together. It depicts a close-up view of interwoven fabrics in varying shades of beige and tan. It’s a simple gesture, like Korman’s painting, presenting a wavering, imperfect grid. It also suggests weaving — traditionally women’s work — as a precursor to the grid as aesthetic framework. The systematic warp and weft of the loom, after all, was the template for the first computer.

Fowler is documenting the women in this show in the film “With It Which It as if It Is Meant to Be, Part II,” which will be screened at the gallery in September.