- Source: ARTSPACE

- Author: EDITORS

- Date: OCTOBER 26, 2016

- Format: DIGITAL

Meet the Upstarts:

Three Fresh-Faced Painters Who Are Changing the Game

Last week, we took a close look at some of the oldest painters from Phaidon’s Vitamin P3, whose works today are as lively and immediate as anyone’s. Here, we’ve turned the tables, focusing on three of their youngest contemporaries (all still in their 20s) who nevertheless represent some of the most vital artistic voices of their generation. Their works prove that an excited, still-seasoning eye can contribute startling innovations, even when rexamining (and reinterpreting) classic movements like Cubism, Expressionism, or art history itself.

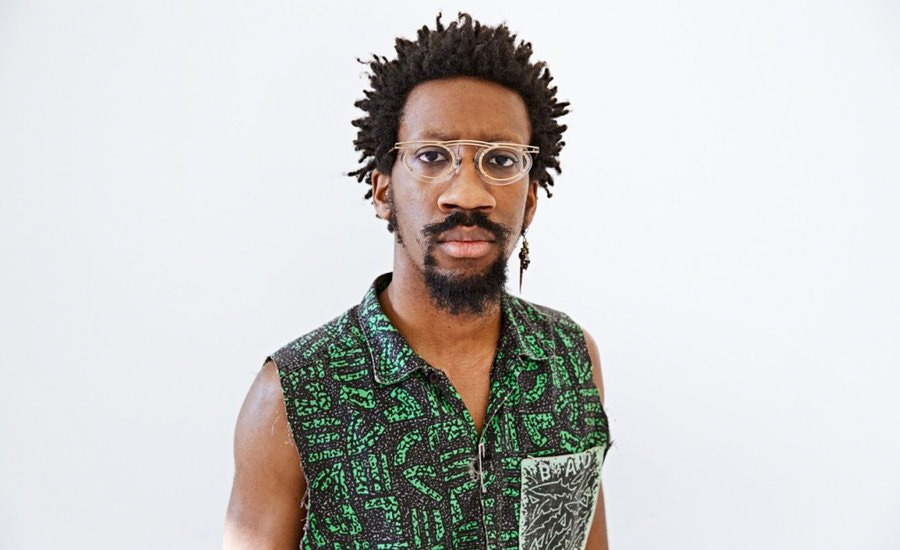

TOREY THORNTON

Born 1990, Macon, GA. Lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

You Say Militia I say Melissa, Or Something. Mostly About Striping, 2015

Torey Thornton’s paintings exude a laid back oddness that belies their formal and structural complexity. The artist lowers the viewer’s expectations from the outset with goofy, absurdist titles such as Swamp Pee Fem Shreck (2015) or You Say Militia I say Melissa, Or Something. Mostly About Striping (2015) or, as with the puzzling title of a 2015 exhibition, “Kneed a Sea Ware Groin.” The paintings, too, like to act dumb, such as Some Traces of Vanity Only for the Sake of the Picture (2014), which features a faceless, cartoonish figure parodying the convention of the artist’s portrait. Thornton prefers paper or plywood panels to canvas, so his large works can appear slapdash or homespun.

All these qualities, however, simply set the tone for an enjoyable succession of small epiphanies that flow from his paintings. Thornton clearly takes pleasure in painting, and wants his viewers to as well. That is not to say that he makes things easy. Much of his work—like his titles, which can sound like cryptic crossword clues—present as riddles to be solved. Take First Cynthia (2014), for example, which at first glance appears to be an arrangement of abstract shapes on a pink ground, redolent perhaps of a roughed-up Jonathan Lasker (b.1948) painting.

One of the last things we notice is the small bunch of pale green grapes, with shadows, on a patch of white that must, logically, represent some kind of platter. The loosely brushed brown area beneath then becomes a table, but soon the picture begins to break down, as different elements refuse to conform to the same representational conventions. (A rough spidery form is incommensurable with a soft, spray-painted green shape nearby.) And surely those yellow lines on the dark grey area in the foreground can’t designate a car park, can they?

First Cynthia, 2014

Thornton is fond of such problems. He is assisted in his mischievous willingness to perplex his viewers by the human mind’s hard-wired inclination to ascribe meaning to form, to project representational content onto abstract shapes and to attempt to resolve those shapes into a three-dimensional space. Of course, the cards are stacked in Thornton’s favor because the paintings insist on their own flatness. By adding collaged elements to his work—often pieces cut from his existing works on paper, but occasionally three-dimensional objects like wooden planks—he further demonstrates that this pictorial space is really only a vertical, depthless plane.

In some works Thornton paints directly onto panels of wooden slats, emphasizing that the picture is merely a surrogate wall. His use of spray paint, along with his street-smart wit, reinforce this association with marks that look like graffiti, as in the huge It’s Late Now, Stores are Probably Opening Up (Queens) (2014). However Thornton’s work owes as much to Henri Matisse (1869–1954) as it does to Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–88). Is that a tiger in the living room, next to the fruit on the coffee table? Or is it a tiger-skin rug? Thornton isn’t telling.

– Jonathan Griffin

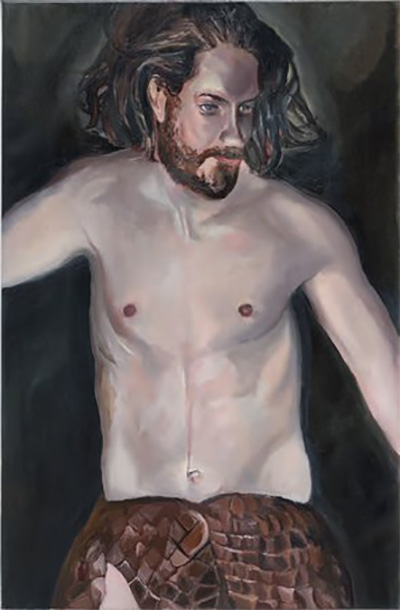

NATHAN CASH DAVIDSON

Born 1988, London. Lives and works in London.

Your flee not fear cauldron stirring wounds, 2015

“Burlesque in which we’ve thrown it on its head” has proven to be a remarkably apt summary of Nathan Cash Davidson’s paintings. The title, derived from Cash Davidson’s exhibition at London’s Parasol Unit in 2010, seems to capture the unsettling mixture of dark surrealism and melodramatic figuration that populates his recent works. Of course, the “burlesque” that Cash Davidson refers to here is not of the risqué faux Victorian sort, but rather burlesque as a “parody, or comically exaggerated imitation of something,” in this case, history painting. In his theatrical style, Cash Davidson’s approach tends to exaggerate, distort, and even pantomime history in a way that is both self-conscious pastiche and, in its strangeness, deeply psychological.

Cash Davidson has in the past painted urban pop culture subjects like Ernö Goldfinger’s famous Trellick Tower in London and the comedian Sacha Baron Cohen’s character Ali G, but the majority of his current work is concerned with the aesthetics and iconography of the Renaissance. This recent turn has brought out a certain similarity to the work of El Greco (1541–1614), legible in pieces such as Your sorrows have a name (2012) or Patrick (2014).

Looking for a more recent reference, we might also notice shades of Peter Doig (b.1959) in a work like Tormented with self-doubt and gripped a heart of gold (2013). But overall, Cash Davidson remains stubbornly idiosyncratic, using heavy blacks and heavily mixed color to frame areas of unexpected detail, accentuating light and shadow in a way that seems to warp the figures and encrust them in their surroundings.

Patrick, 2014

Although he draws inspiration from diverse sources including the Internet, mass media and his own dreams, he insists that his main objective is to “create the past but in the now.” Rather than referencing the art of the Renaissance in any kind of systematic fashion, Cash Davidson is precisely interested in what we might call the second-hand circulation of historical imagery through the channels of mass media and his own psychological landscape. Thus, his bringing history into the present is not as simple as it first sounds, as he is not painting specific scenes from European history, but rather what he sees in the media, as representations of history.

In a sense, these paintings are recasting the circuitous ways that history has already embedded itself in the present through popular culture. If this is history painting, it is history that is found in YouTube clips, clearance sale videotapes, and used bookstores. These are authentically inauthentic renditions of Renaissance portraiture and allegorical scenes, capturing a kind of sleepwalking, schizo-history that continues to unfold in Cash Davidson’s very own world of images.

– Timothy Ivison

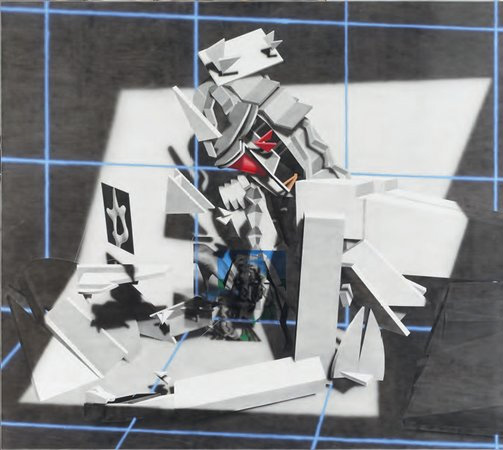

AVERY SINGER

Born 1987, New York, NY. Lives and works in New York.

Happening, 2014

With one foot planted squarely in the digital present and another in painting’s modernist past, Avery Singer uses computer modeling to create arch and lively canvases that explore (and satirize) the condition of the artist. Singer seems playfully self-aware of the figure of the artist caught within a web of enduring clichés, and it is within her minimal, yet complex, aesthetic, and exceedingly of-the-moment digital idiom that we can discover complex conceptual targets.

Singer attended the Cooper Union in New York but graduated in 2010 feeling let down by the experience. She moved uptown to join a few fellow artists in creating a bare-boned communal space in which to live and work, and began experimenting with Photoshop to create flattened digital images that she would then render by hand as graphite sketches. Dissatisfied with the process, she advanced to employing the 3-D modeling program SketchUp—used predominately by architects and engineers—to develop illusionistic constructions of people in virtual settings that she would then transfer to paint on canvas via an overhead projector. This approach, in addition to being strikingly novel, captured a sense of alienation from a more “natural,” unaffected reality and is one that Singer has eagerly exploited since.

A favorite subject of Singer’s is the artist’s studio—nostalgia-infused spaces, full of clichés of romantic poverty, freedom, authenticity, and ambition that she uses 3-D modeling to parody mercilessly. Her blocky, kludgy style of animation seems to dehumanize her subjects, treating them like still lives or puppets that are defined within the logic of a grid, and whose every action is mordantly bathetic. Her black-and-white or muted palette places her subjects in an indefinite temporality—a quality that the artist exaggerates by playing up the multi-dimensional ambitions of Cubism in a banal manner. The ersatz performers caught within Singer’s frame are not exactly revered: in paintings like Happening(2014), three nude women embrace each other while two others bend over and contort before an empty easel. The women wear high-heeled shoes (and nothing else), while elegant shadows atmospherically rake over them. In Director (2014), a long-haired flautist makes a preening appearance, as though art is a distant third priority—coming after posturing.

Untitled, 2015

Across all of Singer’s works, including studies and individual portraits, art history – and, in particular, European modernism—is a vital touchstone. For “Art Basel Statements” in 2015, she produced a room of immersive paintings that was inspired by both Fritz Glarner’s (1899–1972) Mondrian-esque Rockefeller Dining Room at Zürich’s Haus Konstruktiv and the grisaille trompe-l’oeil hallways in the Vatican City in Rome. An earlier series recreated Erich Consemüller’s (1902–57) portrait of a woman in an Oskar Schlemmer mask seated on a Marcel Breuer chair, or the works of Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp and other canonical artists.

Despite the slightly cynical and satirical tone in much of Singer’s work, what is remarkable is that the paintings achieve monumentality and an acute psychological presence. In combining her evident mastery of traditional painting with her synthetic mode of digital modeling, Singer has achieved a new approach to the portrait, the nude, and the interior.

– Andrew Goldstein