- Source: Hyperallergic

- Author: Andrew Schlager

- Date: September 17, 2018

- Format: DIGITAL

Diana Al-Hadid Studies Boundaries While Refusing to Obey Them

In her solo exhibition at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, Al-Hadid continues to let the most elemental, universal facts of bodies morph into unique forms.

The sculptor Diana Al-Hadid, her hands working under a brown cover, a potato sack used like a pillow case, is making a face. Her arms bob, the tarp pulses, she looks away, and the face under the cover forms. She cannot see what she is making. She doesn’t care. Like a pianist she plays this burlap mass, as if hearing her art on her fingers. In this filmed studio visit, Al-Hadid explains that she doesn’t look at the head she’s sculpting because it’s the “only thing on your body you can’t really see.” The claim, so simple, so belatedly obvious, satisfies until the ensuing thoughts swarm: if the only head we can’t see is our own, if this is the logic of self-perception, then is Al-Hadid sculpting her face as she cannot see it? Or is it another’s face, as that other might sculpt it? Or is she suggesting that we warp even the faces of others because we cannot see our own?

In her absorbing show at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, Diana Al-Hadid: Delirious Matter, Al-Hadid continues to let the most elemental, universal facts of having a body deform the bodies we have. The human figures that are found in the show are kind of anti-Pygmalions — not sculpture on the threshold of animation, but sculpture on the precipice of decomposing. Ruins are scattered throughout the show, and Al-Hadid delicately exhumes old sources without papering over their fractures. Her talent is to be clear without being clean, to study boundaries with care, without obeying them.

Diana Al-Hadid, “In Mortal Repose” (2011) Bronze and cast concrete, 190.5 x 194 x 178.8 cm (all images courtesy of the Bronx Museum)

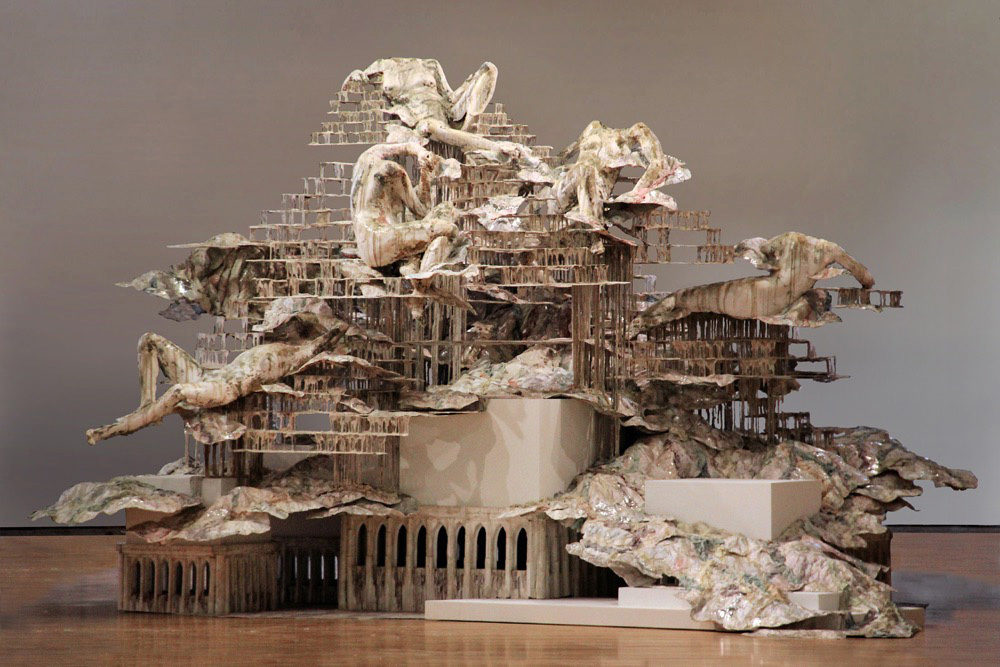

“Nolli’s Orders” (2012), the show’s largest piece and anchor, makes a soft allusion to Bernini’s “Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi,” displayed in the Piazza Navona in Rome, though the reference has dried up. Al-Hadid’s waterless fountain drips over its edges, the actual material of which it is composed (plaster, polymer gypsum, fiberglass, steel)] in icicle-like fragments, as if this fountain froze before getting turned off. Its theater is its dereliction. No burly river gods keep watch along the fountain. Instead, Al-Hadid has placed headless, isolated figures posed around the heap.

The sculpture directly cites Giambattista Nolli’s 1748 map of Rome, revolutionary for its use of shading to distinguish public from private space, and it epitomizes Al-Hadid’s interest in the cartographic. Featured on a nearby wall, a segment of Nolli’s map seems both blueprint and lost cause. As if executing his orders, Al-Hadid builds distressed, model-size Roman arches near the base, but as the sculpture rises, the arches melt. Al-Hadid models not just a fragment of a city, but a city’s eventual decay — the future in which it ceases to matter, has been left to the elements.

The only reflective surface that mimics water is aluminum foil, conspicuously un-ancient and mass produced, cold in refrigerators. This material becomes the skin of the work and its preservation, as if, in a campy finish, the piece was pitched between relic and leftover.

Al-Hadid was born in Aleppo. Her family moved to Ohio when she was five. She knows how to layer and mix these histories of the classical and the contemporary; after all, artifacts from that part of the world are frequently moved from their original sites to new, temporary homes, sometimes stolen, sometimes saved. But here, pieces are jarringly decontextualized of their historical circumstances, as if stand-ins for an experience of immigration, of a new home.

Diana Al-Hadid, “Nolli’s Orders” (2012)

Al-Hadid revisits her old house in the sculpture “Head In The Clouds” (2014). In it, a face adorned with a halo hovers above a coarse, tattered, almost non-anatomical body. It is a body without a situation. Fabric piles beneath the figure, who appears to be covered with a cloak or wings. This saint (or is it an angel?) rises high off its plinth. In an ecclesiastical allusion, this saint holds a model of Al-Hadid’s childhood home in Ohio; in typical religious iconography, saints might hold models of dedicated churches as offerings to Christ. But this is no interventionist American angel, or patron saint of the American Dream welcoming immigrants with the prospect of home ownership. This ragged figure cuts across geopolitical myth. In this era of mass migration and displacement, what might it mean to sculpt, to reference the statuary, to meditate on movement with the stationary? Maybe Al-Hadid means to distrust our ability to ever fully arrive at the place we hope to go. Your house may still, may always, feel like a temporary model. You might feel like a place-holder, until the real you arrives.

Headlessness recurs throughout the show: In “In Mortal Repose” (2011), a bronze, headless, legless body melts off of a cement plinth. Her bare arms and chest, in modern dress, lean at the top, while a pair of feet have fallen below. This piece anticipates three sculptures currently displayed in Madison Square Park, where Al-Hadid has a commissioned exhibition running concurrently and under the same name as her indoor show at the Bronx Museum. On the park’s lawns, three torsos, headless and legless, all titled “Synonym” (2017–2018), melt off of and into their bases, as if the sun had grown too hot.

Though dissolved, these figures have their genders preserved. A lost face might disturb a certain desire for individuality, but headlessness morbidly augments these sculptures’ femininity. If we follow Al-Hadid’s earlier logic in her treatment of heads, there’s the trace of self-perception in these anonymous “Synonyms.” Like a knot of wishbones, a body of ribs, they haunt the bronze sculptures of American Civil War figures, all men, with whom they share the park. These men’s heads endure, but they are by no means easily recognizable. For their faces to have meaning, they depend on the names carved into the plinths and bases on which they rest.

Diana Al-Hadid, “Late Last Night” (2015) polymer gypsum, fiberglass, steel, plaster, aluminum leaf, pigment, 121.9 x 121.9 x 7.6 cm

The show also features a number of Al-Hadid’s wall panels, with surfaces that appear as damaged or as frayed as her sculpture. One, “Late Last Night” (2015) suggests a cluster of anonymous yellow buildings. The gaps and holes here double as windows and arches in the buildings. Because you can see into the holes, the buildings take on a three dimensionality of architecture. Flatness is swallowed by the openings in the cityscape. If these look like paintings, they are leaking sculpture.

Al-Hadid’s practice in these panels is entirely additive. She uses a “controlled dripping” to layer paint mixed with polymer gypsum, around which gaps and absences branch and pool. No material was removed. These holes form not from puncture, but from careful addition. What is missing is brought along with what is added. Each drip carries with it its contagious absence, wherever it trickles. There are pockets of emptiness, of nowhere or elsewhere, included in these places.

It’s as if this delicate play between the present and the missing reframes Al-Hadid’s early emigration. Disintegration and assimilation edge each other. The threadbare abstraction of these panels frustrates any attempt to read these works too biographically, but Al-Hadid’s wall pieces, even at their most rootless, remain intricate. She suggests that there’s an intimacy in not belonging, of not settling in one world. If Nolli’s cartographic innovation distinguished public from private space, we might say in Al-Hadid’s mapmaking, where you are present contours where you might not belong. Our vision falls off as we see through her panels and her sculptures: where her material goes missing, so do our eyes. We are blind to where we are under the pressure of where we’ve come from. If Al-Hadid sculpts faces without seeing them, announcing how we fail to see our own heads, she puts places under erasure to show how we fail to inhabit them permanently.

Diana Al-Hadid: Delirious Matter continues at the Bronx Museum of the Arts (1040 Grand Concourse, Fleetwood-Concourse Village, the Bronx) through October 14.