- Source: The New York Times

- Author: Su Wu

- Date: June 23, 2015

- Format: PRINT AND DIGITAL

A Two-Year, 100-Billboard Celebration of Going West

Eve Fowler

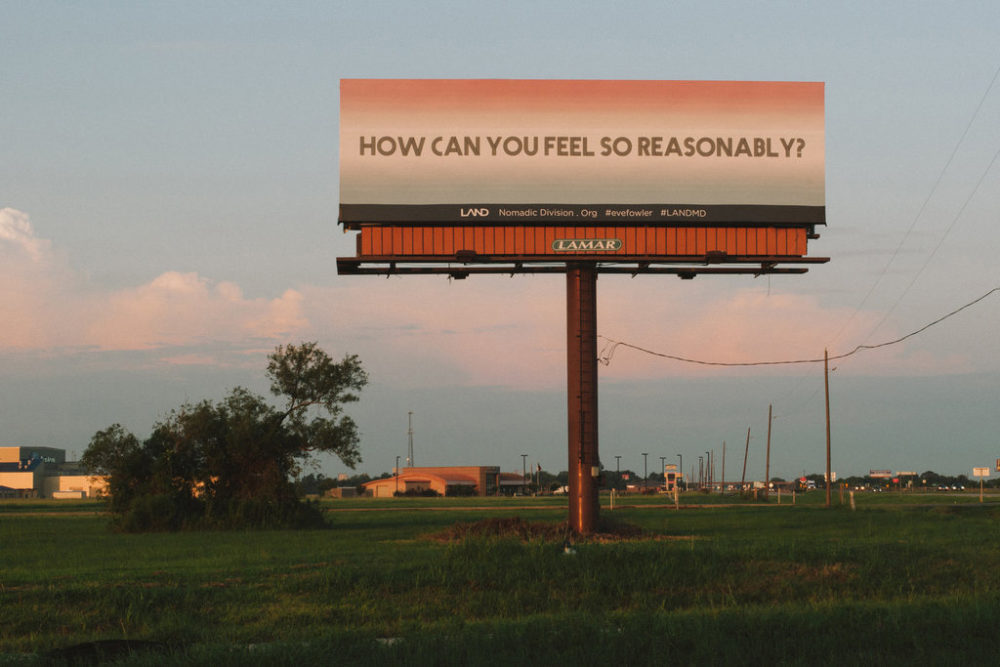

The fourth chapter, Eve Fowler’s “it is so, is it so,” 2014, was displayed in Houston, Tex.

Though blizzards and rent checks will always revive New Yorkers’ dreams of avocado trees and sunshine, for a certain set of creatives, the allure of the American West is so passé it’s history. Starting tonight, the “Manifest Destiny Billboard Project,” a two-year, 100-billboard journey from sea to shining sea along Interstate 10, kicks off its culminating festivities in Los Angeles. “Transit west has a long and speckled past, a combination of the best and worst things about what we do,” says the director of the public-art nonprofit Los Angeles Nomadic Division, Shamim Momin, who co-curated two Whitney Biennials before herself moving to California. The vision of manifest destiny, she says, has had “all sorts of applications over time, many of which have been devastating to different communities. And yet it is also so ingrained in the history of being American, the way we think about aspiration and ambition, achievement and taking. It ties to everything from the capitalist impulse to notions of exploration, and to the desire to know.”

In addition to an exhibition at LAND of some of the commissioned billboards – from artists including John Baldessari, Jeremy Shaw and Shana Lutker – the beach celebration will also involve a sequentially unfolding 10-course dinner from the Fainting Club, a “ribbon-tying” ceremony, a perfume-making workshop distilling the smell of L.A. and film screenings and panels all week, including one at the carousel at the end of the Santa Monica Pier. “When I finally made my way to New York and then Los Angeles, I had to wrestle with a profound disappointment,” says the artist Matthew Brannon, whose series of 10 billboards advertising imagined narratives such as “New New York Sucks” is the last “chapter” of the more than 2,700-mile project. “With each billboard, I wanted its interpretation to be not just open but frustrating. Is ‘New New York’ Los Angeles itself? And why does it suck? Or is it really just a tease or reference to the ongoing, endless and silly opinions each city has about the other?”

Coasts may demarcate edges, but the looming “Manifest Destiny” billboards in-between, from Mobile to New Orleans to Palm Springs, offered another sort of unboundedness. In Las Cruces, N.M., works by the artist Daniel R. Small featuring a made-up typography – a combination of Greek, Hebrew and proofreading marks – inspired a reported protest at the base of a sign over concern about the infiltration of terrorist messages. In Houston, the artist Eve Fowler opened free lending libraries at gas stations of texts related to her pieces, which featured excerpts from the writings of Gertrude Stein. “A nomad isn’t someone who is an itinerant: that’s how they live and practice their life. They still have places they go back to or ways of doing things that they carry with them,” says Momin, who first conceived of the cross-country billboard project with co-curator Zoe Crosher during a period when the artist commuted through the Mojave, the “anticipatory desert” a physical reminder of the mythos of finally arriving in L.A. “Unlike travelers, nomads will stay in certain places for a certain amount of time, so there is investment in their place and site,” Momin says. “It just isn’t permanent.”